Humphrey Hawksley, Asian Waters: The Struggle over the South China Sea and the Strategy of Chinese Expansion. Overlook, 2018. $29.95 (304p) ISBN 978-1-4683-1478-6

By Shu Wan, Department of History, University of Iowa

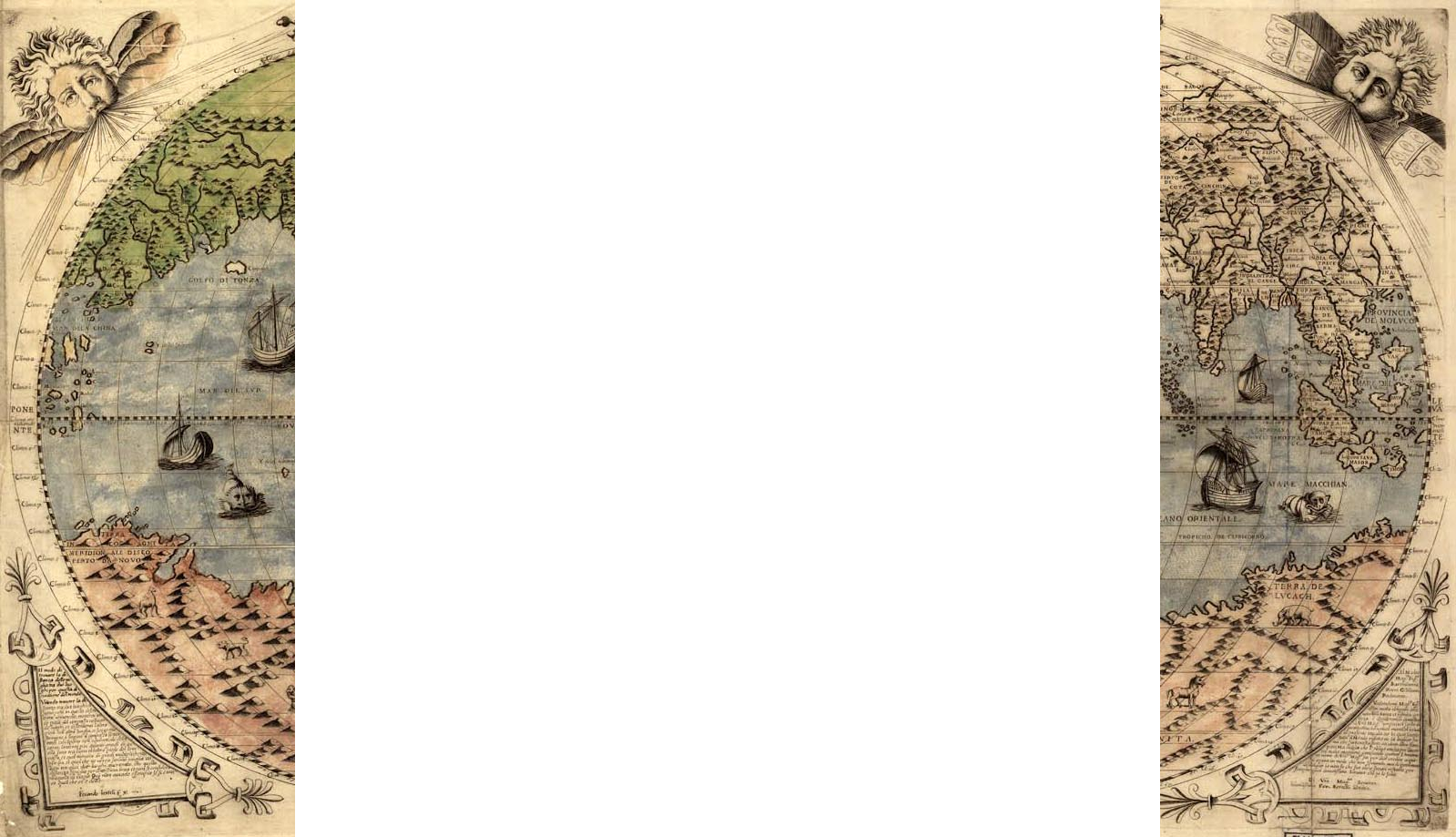

As an experienced British correspondent travelling through multiple Asian countries for decades, Humphrey Hawksley tends to make a meticulous examination of the current international disputes over the South China Sea in his volume Asian Waters: The Struggle over the South China Sea and the Strategy of Chinese Expansion. Situating this dispute in the broader context of China’s rising international power, Hawksley’s intention is to shed light on the political implication of the disputes. Examining the current events involving the South China Sea through a historical lens, he argues that the Philippines, Vietnam, India and even the United States take a sharp notice of the Chinese presence in the South China Sea. The author considers the Great Navigation and the post- Columbus explorations of the New World around 1500 paving the way for the extended imperial expansion of the West in the following centuries, China’s current conflicts over the Sea with other coastal countries and the international great powers may symbolize a new episode in human history.

The organization of this volume consists of four parts, which respectively discuss the standpoints of the countries involved with the controversy. Ranging from China, India, Southeast Asian countries to the U.S. and its allies in East Asia, countries across the world take the continental issues in Asia for granted. With extensive interviews with people of different nationalities and social backgrounds, ranging from Philippine fishers and Chinese intellectuals and American diplomats, Hawksley illustrates the various facets of the international conflict surrounding the South China Sea. For the Chinese government and its people, their military and civilian activities in the Sea supported their claim of sovereignty over some islands which western imperialist countries robbed from them in the early twentieth century. On the other hand, derived from the concern about the risk of Chinese expansion into the Indian Ocean, the Indian government perceives the presence of Chinese militant and civil forces in the Sea as a prelude to further invasion into South Asia. At the same time, for the average person living in Southeast Asian countries, the Chinese government’s claim of those islands indicates that these islands’ natural resources and territories have an increasing lure. Finally, for America and its allies in Asia, it is doubtless that the rise of China poses a great menace to the existing world order in which western national interests are embedded. Backing Vietnam’s and the Philippines’ claims of the Spratly Islands, the Scarborough Shoal and other territories in the Sea, these countries condemn China as a trouble-maker and a spoiler in the world order.

Taking the disputes over the Sea as an example, Hawksley presents an overview of the rise of China as an emerging superpower. Beyond the geographical limits of Asia, China’s enhanced national power is projected in its claim of sovereignty over multiple islands in the Sea. Contrary to the majority of western observers, Hawksley eschews the prevalent tendency of recklessly imposing moral judgments of wrong or right on the Chinese government’s policy in the Sea. As he contends, the tension between China and other Asian countries could not be oversimplified to a model of “attacker” and “defenders.” Other Asian countries seemed to misunderstand the Chinese government’s intention to take tentative efforts in moderating the existing world order on the basis of Westphalian sovereignty.

Hence, the real solution to the disputes over the Sea will be built on the ground of mutual comprehension and on the compromise between every political and personal actor. As Hawksley notes in the conclusion, “negotiations to restructure the world order would be best based on pragmatism rather than fear and self-interest, and they would take decades. Everyone, whether an American or Chinese president, a Brazilian sugarcane cutter, an Indian brick kiln worker, or a Vietnamese fisherman, should feed in some way involved. Such as forum would be fraught with obstacles, breakdowns, and challenges.” (264) With his rich knowledge of the different countries’ standpoints and their concerns about the Sea, Hawksley predicts a harmonious and bright future for the world.