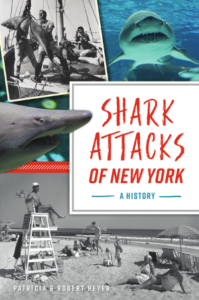

Patricia and Robert Heyer, Shark Attacks of New York (Charleston: History Press, 2021. 21.99 USD, ISBN: 9781467144988, Paperback, 112 pages, 38 illustrations.

By Erin Becker-Boris

In Shark Attacks of New York, Patricia and Robert Heyer chart the thirty-three shark/human encounters (as documented in the New York Shark Attack File) along the New York waterfront from 1642 to the present. The authors bring together environmental history, social history, New York City history, and marine ecology to chronicle “two creatures, both at the top of their food chains, and what can occur when their paths intersect” (9). Though this book was written for a popular (rather than strictly academic audience), the authors have compiled an accessible work with far reaching significance: 1) the authors have presented an interesting and engaging way to access New York history at the waterfront, 2) the authors’ investigation into each ‘attack’ de-sensationalizes the encounters and allows us to look at human-animal interactions in a more balanced way and 3) the authors have presented a very compelling discussion on the influences exerted on historical journalism. The authors move chronologically through 379 years of New York history at the waterfront, drawing from historic news articles, the writings of Washington Irving, the research of ecologists, and more to present a surprisingly nuanced and accessible narrative in only 96 pages.

In Shark Attacks of New York, Patricia and Robert Heyer chart the thirty-three shark/human encounters (as documented in the New York Shark Attack File) along the New York waterfront from 1642 to the present. The authors bring together environmental history, social history, New York City history, and marine ecology to chronicle “two creatures, both at the top of their food chains, and what can occur when their paths intersect” (9). Though this book was written for a popular (rather than strictly academic audience), the authors have compiled an accessible work with far reaching significance: 1) the authors have presented an interesting and engaging way to access New York history at the waterfront, 2) the authors’ investigation into each ‘attack’ de-sensationalizes the encounters and allows us to look at human-animal interactions in a more balanced way and 3) the authors have presented a very compelling discussion on the influences exerted on historical journalism. The authors move chronologically through 379 years of New York history at the waterfront, drawing from historic news articles, the writings of Washington Irving, the research of ecologists, and more to present a surprisingly nuanced and accessible narrative in only 96 pages.

In Shark Attacks of New York, Patricia and Robert Heyer have put together a compelling narrative which engages with New York history at the waterfront; their work is strengthened by the way in which the authors contextualize each ‘attack’ within New York city/Long Island social and labor history. For example, when discussing the fatal shark attack on three unnamed youths and one man at Prince’s Bay, Staten Island in August 1858, the authors contextualize their narrative within broader discussions of economic tension, the seeds of the Civil War, the influx of German and Irish immigrants, and the spread of infectious disease. The Marine Hospital Compound in Staten Island was used to quarantine immigrants suspected of being “a health threat” in an attempt to control infectious disease; Heyer and Heyer write, “On numerous occasions, residents contracted some of the many illnesses treated there. There were fatalities… The community blamed the quarantine station. By the end of August 1858, tensions had reached a boiling point” (16). Due to the upheaval in the town, “it was left to the boys’ fathers and uncles to search for the missing lads” and the man’s disappearance went unremarked on (18). Local residents stockpiled flammable materials, stormed the Staten Island office of the New York Board of Health, cut the fire department’s hoses, and burned the entire hospital complex to the ground. The unrest resulted in a lack of reporting on the shark attacks. With each shark encounter, the authors take the opportunity to walk their reader through the state of the city in a way that makes it more real and accessible. Each ‘attack’ in Shark Attacks of New York becomes a window into the impact of war, labor movements, urbanization, and food production on the New York of the past.

Heyer and Heyer approach their narrative understanding that the general public typically holds a high level of fear of sharks. In their introduction, they write, “these crowded beaches can be emptied with the shout of a single word. Restaurants and hotels are abandoned, and boardwalks and amusement parks grow silent, bringing the local economy to a screeching halt. That one shouted word is ‘Shark’!” (7). Their work develops alongside interesting work by psychologist Blake Chapman, who argues that humans developed a “suite of ways to protect ourselves”, including fear as an important survival strategy; even though we have learned the risk of experiencing a shark attack is low, we retain that ancestral fear of predators, including sharks.1 Chapman boils his argument down even more succinctly. “Due to fear, the potential damage sharks are able to inflict on us, and our complete inability to control these animals, they do tend to get a bad reputation”2 Heyer and Heyer’s investigation into each ‘attack’ in New York history de-sensationalizes the encounters and allows us to look at human-animal interactions in a more balanced way. Many of the ‘attacks’ described in their work are more encounters than attacks—sharks bumping into swimmers, humans spotting (and killing) harmless species of sharks out of fear, humans receiving minor bites while hooking or reeling in sharks, etc. In one account, Catherine Beach, a model for Koster & Bials Music Hall in Manhattan, swims in the East River on a day off, notices a large fish swimming behind her, and climbs into a friend’s rowboat; a nearby boater “pulled a revolver from his satchel and emptied it into the shark” (52). The shark ended up being a forty pound bonnethead shark- “harmless to humans, feeding on crustaceans and small fish. It is likely that the shark was merely following the warm waters and wandered into the river, resulting in an unfortunate encounter with Catherine Beach” (53). Heyer and Heyer also provide demystifying explanations for violent attacks. For example, while discussing the 1864 attack on thirteen year old Henry Brice off the offal dock on Thirty Ninth Street in Manhattan, the authors tie together human actions and animal behavior. This attack took place in the Meatpacking District, one of the nation’s largest meat-processing centers, where animals were slaughtered, cleaned, and rough butchered on the offal dock. According to Heyer and Heyer, “Entrails and other waste products were dumped into the Hudson River and allowed to float downstream” (26). They assert, “While it may have come as a surprise to some New Yorkers that sharks were found in the Hudson River, those who worked in the Meatpacking District were not at all surprised. They had been reporting seeing hungry sharks feeding off the byproducts of the offal docks for several years” (27).

Throughout Shark Attacks of New York, Heyer and Heyer draw attention to the influences exerted on historical journalism and to what information enters the historical record. This attention is best encapsulated in their account of the August 22, 1898 attack on Charles Boone at Prince’s Bay, Staten Island. The authors draw from three different accounts of the attack as detailed in the New York Times, the Lima News, and the Milwaukee Journal. While swimming in shallow water, Boone was struck by a shark. While the Times presented a subdued account of the attack, the other two include dramatic descriptions of the event, Boone’s injuries, and the crowd’s reaction. Heyer and Heyer provide potential explanations for the differences: “Can we attribute it merely to lazy reporters who used secondary sources? Or did they perhaps embellish the story to make it more exciting for their readers?” (56-57). The authors almost present a third potential explanation, not unfamiliar to anyone who has seen the 1975 cult classic, Jaws. “There is the real possibility that the New York paper purposefully presented a subdued account of the attack. It certainly would not be the first time the press downplayed shark incidents in local waters, especially during the busy summer tourist season” (57).

At only 96 pages, Shark Attacks of New York is a surprisingly nuanced and detailed work steeped in New York social history and local ecology. Whether used as a fun introductory text for an undergraduate survey course or as a pleasure read, Heyer and Heyer’s work is thought provoking, engaging, and worth the read.

Erin Becker-Boris is an independent historian from Long Island, NY. Her research interests focus on the convergence of women, labor, and the environment through a global extractive maritime economy. Her work in museums grapples with investing local peoples in their resources as stakeholders through outreach, education, and the development of new public programming. She has written for Gotham Center for New York City History, New York Almanack, Read More Science, H-Net Environment, and the Journal of Urban History. She can be found at @ErinE_Becker on Twitter. You can find more of her work on her profile at Women Also Know History.

- Marc Bekoff, “Shark Attacks: Myths, Misunderstandings, and Human Fear : An interview with Author Blake Chapman,” Psychology Today, November 8, 2017. https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/animal-emotions/201711/shark-attacks-myths-misunderstandings-and-human-fear [accessed December 6, 2021].

- Ibid.