Thank you to Graham Moore for this fantastic guest post. This article argues for the utility of information contained within the High Court of Admiralty’s criminal deposition records for recovering histories of early modern maritime life. In order to properly assess how these records might be used for that aim, it is first necessary to understand the nature of the information therein – how it was gathered, for what purpose, and within what context. This article uses selected information from the records held in TNA’s HCA 1 to further reconstruct the court’s procedure.

Graham Moore is a PhD student working as part of a Collaborative Doctoral Partnership between the University of Reading and The National Archives, and an Associate Lecturer at the University of Reading. His research interests include piracy, maritime law, and seafaring communities in the early modern period; Graham’s CDP project, entitled ‘Prosecuting Piracy in Peacetime’, focuses on the early seventeenth-century criminal records of the High Court of Admiralty. Recent publications include: ‘The Liues, Apprehensions, Arraignments, and Executions of the 19 Late Pyrates: Jacobean Piracy in Law and Literature’ (Moore, 2022) in the open-access journal Humanities. Special thanks to Dr Daniel Gosling (Early Modern Records Specialist, The National Archives) for bringing HCA 1/50 and HCA 1/60 to the author’s attention.

The extensive High Court of Admiralty records, held at The National Archives in Kew, London, have long proven a key resource in reconstructing Anglophone histories of the maritime. Prior to its erosion by more London’s more competitive common law courts, the High Court of Admiralty (HCA) was a profitable institution operating with near-exclusive jurisdiction over maritime causes.1 Where common law courts were restricted by the terrestrial and county-based construction of juries, and differed too broadly from other European legal systems to easily (and favourably) treat international causes, the Admiralty courts filled a vital niche on behalf of England’s maritime community.2 This article adds to an ongoing effort within scholarship to use the High Court of Admiralty’s criminal records to reconstruct aspects of early modern maritime life, by utilising evidence from court depositions to reconstruct the court’s (often undescribed) criminal procedure.

The majority of the court’s activity was focused on its ‘instance’, or civil, jurisdiction. This side of the court dealt primarily with ‘commercial’ business, including wages, contracts, collisions, costs, and property.3 However, this article will focus instead on the criminal side of the High Court of Admiralty, and the corresponding records held in the series TNA HCA 1. Perhaps even more directly than the Admiralty’s instance jurisdiction, the criminal court enabled the state to directly exert influence over maritime activity; its authority, delegated from Crown to Admiral to judge, gave England’s legal system an avenue to approach all ‘things done on the sea’ (super altum mare).4 The criminal court heard cases on seaborne activity including piracy, mutiny, and murder.5 It also covered actions which constituted a more material injury to the rights or properties of the Crown itself, such as the evasion of customs, salvage and wrecking droits, and liability for navigational hazards.6

It is piracy, perhaps unsurprisingly, that has most captivated the interest of readers and researchers in HCA 1. Indeed it is also piracy, and attempts to suppress it, that tends to comprise the majority of the HCA’s criminal records; the court itself was historically preoccupied with the problem of piracy, particularly during the seventeenth century. But despite, and sometimes even because of, this preoccupation, the records in HCA 1 also offer a fascinating glimpse into the maritime world. Senior, for whose 1976 work A Nation of Pirates HCA 1 provided the backbone of evidence, writes that the documents ‘contain detailed information about seamanship and pirate life which are of particular interest to the historian, although to court officials at the time they must have appeared as little more than colourful irrelevancies’.7 This is broadly true – there is much amongst HCA 1’s finer details to entrance the historian, often seemingly off-topic to the case at hand – but properly understanding the nature of the evidence contained therein, and rendering it useful to the historian, requires an understanding of why that information is, nevertheless, found there. In order to properly use the ‘colourful irrelevancies’ of HCA 1, we must first understand the nature of the court’s approach to information and the nuances of its procedure.

Unfortunately, this is easier said than done. It appears that the HCA clerks’ idea of what constituted ‘irrelevancies’ extended not only to the more mundane facets of maritime life, but also to the more everyday functions of the court itself. Simply put, there is no singular extant record of the court’s procedure.8 Not only is it then difficult to join the dots between remaining items of paperwork, but the effort is further obstructed by the weighted scarcity of those dots themselves. Whilst items of evidence (such as the aforementioned depositions) were typically retained, documents which initiated and concluded cases (acts of court such as warrants, indictments, charges, etc.) are far more piecemeal. Unlike the instance side of the HCA, which typically retained the libel documents outlining the complaint which originated a case, the criminal jurisdiction – particularly when relying on its standing commission of oyer and terminer (discussed below) – often relied on a more generic system of warrants.9

Complications only increase when noticing that the clerks across the HCA’s instance and criminal jurisdictions were even less interested in recording the process of arbitration, or any settlements that took place out of court – this in contrast to other courts like Chancery, whose act books did note such events.10 The researcher is thus left awash with tides of information, but bereft of any clear life-raft of context. We are presented, as Berckman evocatively puts it, with a ‘giant documentation that surrounds this curious emptiness’.11 Although complainants could generate a cause by referring a crime to the court, and deposit articles advising the court’s interrogatories (the set of questions issued to deponents during the preliminary gathering of oral evidence), the state (here the Admiralty) often initiated the legal action under its general inquiry into matters of maritime crime. This can result in a scarcity of immediate evidence, requiring the researcher to better understand the overall function of the court in order to fill those gaps and make reasonable sense of the case.

After a pair of Henrician statutes in 1535 and 1536, the High Court of Admiralty was able to hear criminal cases under commissions of oyer and terminer (to hear and to determine).12 This allowed the court to borrow aspects of common law trials without adhering to the common law itself; for example, instead of necessitating a confession or non-complicit eyewitness to successfully indict capital crimes like piracy, the court could now utilise a form of jury trial.13 This was far more reliable, and enabled the state to act more directly against unruly seafarers who engaged in illegitimate maritime raiding.14

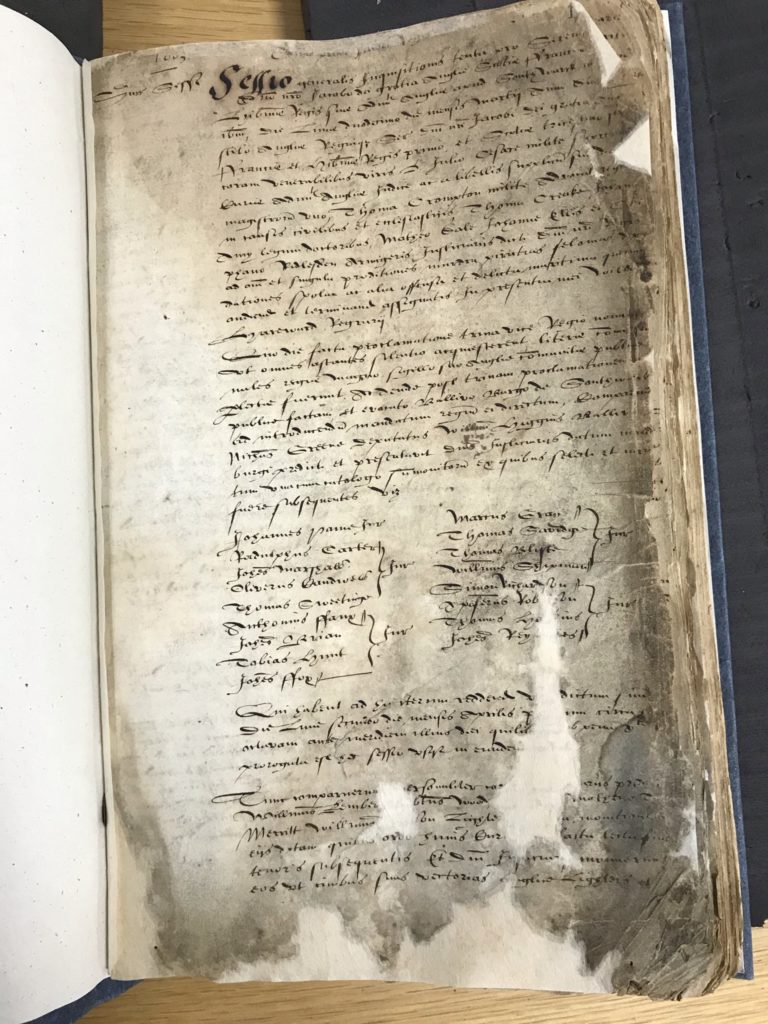

In theory, an oyer and terminer commission was supposed to be issued by the Crown (or delegated authority) to specified agents, to go forth and solve specific problems on a one-off basis. However, it seems that the 1535/6 statutes instituted a sort of ‘standing’ commission for the court. Records held in TNA HCA 1/60 (‘Minutes of proceedings’) provide an example of this standing commission, or ‘general inquiry’ (generalis Inquisitionis), in action.15 A document from 1603 (Fig. 1) opens a session of general inquiry, empowering the courts judges (Julius Caesar, Thomas Crompton, and deputies including Thomas Creake and John Amy) to act with the King’s authority and hear and determine causes relating to ‘murdra piratas felonias depredationes spolia ac alia offense et debicta maritima’ (‘murder, pirates, felonies, depredations, spoil, and other maritime offences and disputes’; official court acts of the HCA were still in Latin at this time but not, evidently, very good Latin…!). The acts book also contains evidence of the court’s marshals (and their deputies) actively reporting to the court’s Sergeant, confirming the attendance of witnesses and deponents in relation to ongoing causes.16

This begins to give us an idea of the court’s remit, and of the standing commission as a constant – yet necessarily reiterated – basis for the activity of the HCA’s criminal body. However, it can be difficult to recover specifics of which causes the court could or could not approach under its standing commission. Specific commissions of oyer and terminer, which effectively created a new cause and empowered designated agents of the court to go forth and hear upon it, were still issued to tackle some problems. In 1608, for example, a commission of enquiry was issued to examine corruption within the navy itself.17 Dated 30 April, the document first acknowledged the extra-ordinary circumstances which necessitated its creation:

“Whereas we are informed that very great and intolerable abuses, deceits, frauds, corruptions, negligences, misdemeanours and offences have been and daily are perpetrated, committed and done against the continual admonitions and directions of you our High Admiral by other the officers of and concerning our Navy royal…”18

The parameters of the commission were then laid out. Should at least three of the ten commissioned agents agree to an action, they would then be able to examine witnesses, view account books and registers, and see any relevant warrants and discharges.19 However, this commission was less than successful; court politics (and royal favouritism) resulted in the worst offenders, such as treasurer Sir Robert Mansell and Lord Admiral Nottingham, avoiding most repercussions.20 A further commission in 1613 was effectively blocked by Mansell as being an overreach of central authority into Admiralty affairs, and only a greater concern about the navy’s overall financial situation enabled a commission in 1618 to partially achieve its aims, slightly reducing Admiralty corruption and inefficiency.21

Other commissions issued during the early seventeenth century, including those to investigate piracy in the maritime counties and Ireland, also proved to have only limited effects. Where agents of the High Court of Admiralty were forced to interact with other administrative bodies and empowered interests (including regional governance structures such as those in Ireland and Devon), these specific commissions of enquiry often proved insufficient. Impacts, where achieved, were ‘highly variable and short-lived’.22 Yet whilst these commissions often failed to achieve their aims, they are nevertheless useful to the researcher as they arose when the HCA’s standing commission was insufficiently capable of tackling an issue. In this way, they highlight gaps in the court’s ability to conduct general inquiries.

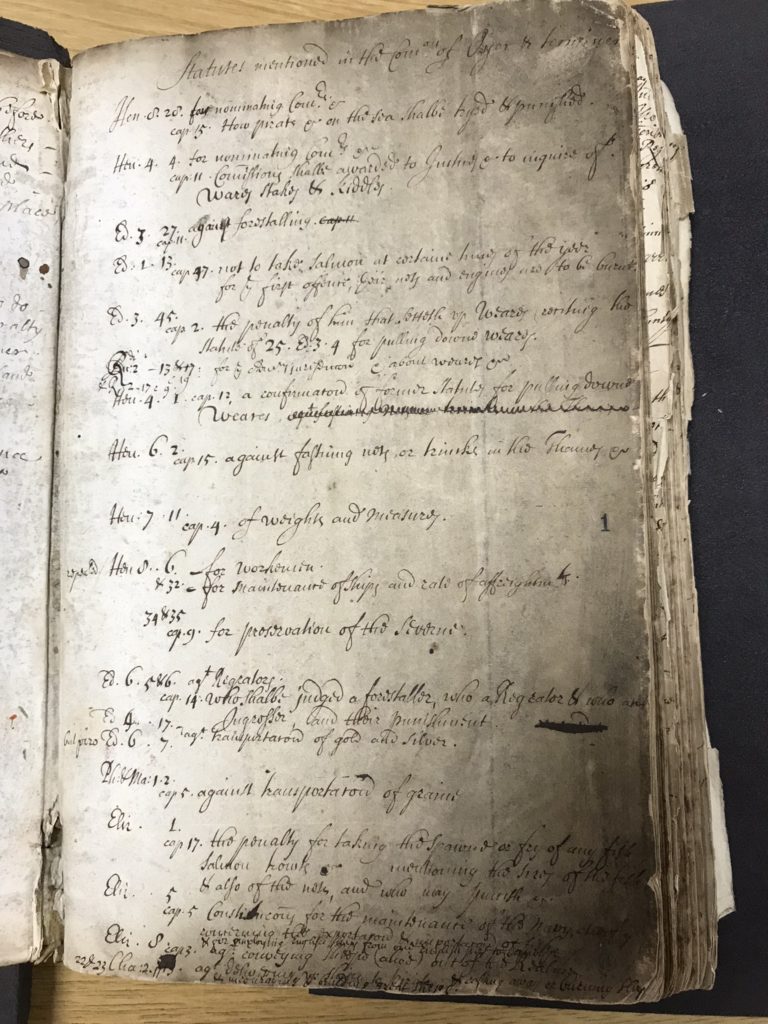

A lucky find in HCA 1/51, the deposition book covering 1674-1683, sheds some further light on the extent of the standing ‘general inquiry’ (Fig. 2), listing ‘Statutes mentioned in the [Commission] of Oyer & Terminer’.23 The list of statutes notes the court’s authority for tackling the offences detailed in the depositions. The ability to tackle piracy, of course, makes an early appearance – but other items are less immediately obvious, and therefore more intriguing. Statutes against blocking navigation on the Thames and ‘for preservation of the Severne’ are iterated, as well as limitations on the transport of certain goods including grain. My personal favourite is the several statutes governing salmon fishing, including the prevention of unseasonal fishing and ‘the penalty for taking the Spawne or fry of any fish Salmon trouts & mentioning the sizes of the fish & also of the netts’.

Procedural notes like this list of statutes are rare, and all the more interesting for that reason. Subsequent folios in HCA 1/51 also include a formal declaration of ‘the letters of ongoing commission for the English Admiralty’s deliberations to hear, listen, and gaol’ on such offences (‘tenor literarum commissionalium oyer et terminer et gaola delibnis pro Admiralitate Anglia’; Fig. 3).24 This, too, offers an exciting insight into the function (and formality) of the High Court of Admiralty during this time period. For the researcher seeking to use HCA records – whether to directly maritime criminality, or to ‘read against the grain’ and approach the maritime and littoral social worlds – an understanding of the court’s procedures is key to analysis. If we admit – as we must – that the ‘trustworthiness’ of legal testimonies is always going to be debatable, then better knowledge of the court itself will always aid historical research by producing a more critical study of the information found within.25

Bibliography

Appleby, J.C., ‘Pirates and Communities: Scenes from Elizabethan England and Wales’, J.C. Appleby, P. Dalton (eds.), Outlaws in Medieval and Early Modern England: Crime, Government, and Society, c. 1066-1600 (Taylor and Francis, 2009), pp. 149-172.

Baer, Joel, British piracy in the golden age: history and interpretation, 1660-1730, volume 2 (Routledge, 2007).

Baker, John, ‘Admiralty Courts and Courts Martial’, The Oxford History of the Laws of England: Volume VI 1483-1558 (Oxford, 2003), pp. 209-219.

Baker, John, Introduction to English Legal History, 5th Edition (Oxford University Press, 2019).

Berckman, Evelyn, Victims of Piracy in the Admiralty Court, 1575-1678 (Hamish Hamilton, London, 1979).

Blakemore, Richard, ‘The Legal World of English Sailors, c. 1575-1729’, M. Fusaro, B. Allaire, R.J. Blakemore, T. Vanneste (eds.), Law, Labour and Empire: Comparative Perspectives on Seafarers, c. 1500-1800 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), pp. 100-122.

Cumming, C. S., ‘The English High Court of Admiralty’, Tulane Maritime Law Journal, Vol. 17, No. 2 (1993), pp. 209–255.

Costello, K., The Court of Admiralty of Ireland, 1575-1893 (Four Courts Press, 2011).

Foucault, M., Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, tr. A. Sheridan (Penguin, 1975; 1991).

Hanna, M., Pirate Nests and the Rise of the British Empire, 1570–1740 (University of North Carolina Press, 2015).

Hubbard, E., Englishmen at Sea: Labor and the Nation at the Dawn of Empire, 1570-1630 (Yale University Press, 2021).

McGowan, A.P., ‘The Jacobean Commissions of Enquiry, 1608 and 1618’, Navy Records Society, Vol. 116 (1979).

Senior, C.M., A Nation of Pirates: English Piracy in its Heyday (David & Charles, 1976).

Steckley, George F., ‘Instance Cases at Admiralty in 1657: A Court “Packed up with Sutors”’, Journal of Legal History, Vol. 7, No. 1 (1986), pp. 68–83.

Steckley, George F., ‘Litigious Mariners: Wage Cases in the Seventeenth-Century Admiralty Court’, The Historical Journal, Vol. 42, Issue 2 (June 1999), pp. 315-345.

Steckley, George F., ‘Collisions, Prohibitions, and the Admiralty Court in Seventeenth-Century London’, Law and History Review, Vol. 21, No. 1 (Spring, 2003), pp. 41-67.

TNA, ‘High Court of Admiralty: Oyer and Terminer Records’, HCA 1: Introductory Note.

Footnotes

- R. Blakemore, ‘The Legal World of English Sailors, c. 1575-1729’, M. Fusaro, B. Allaire, R.J. Blakemore, T. Vanneste (eds.), Law, Labour and Empire: Comparative Perspectives on Seafarers, c. 1500-1800 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), p. 109. J. Baer, British piracy in the golden age: history and interpretation, 1660-1730, volume 2 (Routledge, 2007), p. viii.

- J. Baker, Introduction to English Legal History, 5th Edition (Oxford University Press, 2019), p. 132. C.S. Cumming, ‘The English High Court of Admiralty’, Tulane Maritime Law Journal, Vol. 17, No. 2 (1993), pp. 231, 234.

- J. Baker, ‘Admiralty Courts and Courts Martial’, The Oxford History of the Laws of England: Volume VI 1483-1558 (Oxford, 2003), p. 211.

- K. Costello, The Court of Admiralty of Ireland, 1575-1893 (Four Courts Press, 2011), pp. 33-34.

- TNA, ‘High Court of Admiralty: Oyer and Terminer Records’, HCA 1: Introductory Note.

- These offences are all of one broader rhetorical category, inasmuch as crime, generally speaking, constitutes an attack on or injury to a sovereign power: M. Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, tr. A. Sheridan (Penguin, 1975; 1991), p. 47.

- C.M. Senior, A Nation of Pirates: English Piracy in its Heyday (David & Charles, 1976), p. 14.

- E. Berckman, Victims of Piracy in the Admiralty Court, 1575-1678 (Hamish Hamilton, London, 1979), p. 5.

- Steckley’s work is perhaps the prime example of how to ‘reconstruct an individual case’ from the wide assortment of Admiralty instance records: G.F. Steckley, ‘Instance Cases at Admiralty in 1657: A Court “Packed up with Sutors”’, Journal of Legal History, Vol. 7, No. 1 (1986), p. 70. Work on the instance side of the court can also run into a similar yet divergent issue, wherein the court was not required to record the reasons behind its final decisions on equity cases. Instead the historian is ‘forced, in the general absence of citations or explanations, to rely on what successful plaintiffs usually set out to prove and what their witnesses were prepared to testify’: G.F. Steckley, ‘Collisions, Prohibitions, and the Admiralty Court in Seventeenth-Century London’, Law and History Review, Vol. 21, No. 1 (Spring, 2003), p. 51.

- G.F. Steckley, ‘Litigious Mariners: Wage Cases in the Seventeenth-Century Admiralty Court’, The Historical Journal, Vol. 42, Issue 2 (June 1999), p. 325.

- Berckman, Victims of Piracy, p. 5.

- 27 Henry VIII c.4 (1535). 28 Henry VIII c.15 (1536).

- Baker, ‘Admiralty Courts’, p. 212. TNA, HCA 1: Introductory Note.

- M. Hanna, Pirate Nests and the Rise of the British Empire, 1570–1740 (University of North Carolina Press, 2015), p. 31. Baer, British piracy in the golden age, p. viii-ix. However, Appleby notes that it was not broadly successful in repressing piracy or its terrestrial support structures: J.C. Appleby, ‘Pirates and Communities: Scenes from Elizabethan England and Wales’, J.C. Appleby, P. Dalton (eds.), Outlaws in Medieval and Early Modern England: Crime, Government, and Society, c. 1066-1600 (Taylor and Francis, 2009), p. 155.

- TNA, ‘High Court of Admiralty: Oyer and Terminer Records. Minutes of proceedings’, HCA 1/60/ff.1r-1v.

- TNA HCA 1/60/f.1v, and further.

- Senior, A Nation of Pirates, pp. 134-135.

- A.P. McGowan, ‘The Jacobean Commissions of Enquiry, 1608 and 1618’, Navy Records Society, Vol. 116 (1979), p. 2.

- The ten commissioners were as follows: Sir Thomas Parry, Sir Edward Phillips, Sir John Doderidge, Sir Henry Hobart, Sir Francis Bacon, Sir William Wade, Sir Christopher Parkins, Sir Robert Cotton, Sir Thomas Crompton, and John Corbet. The commissioners examined 161 witnesses during the course of their investigation, and were able to do so remotely, sending statements back to the central authority as a record of their due process: McGowan, ‘The Jacobean Commissions of Enquiry’, pp. 3-4.

- McGowan, ‘The Jacobean Commissions of Enquiry’, pp. xiv-xvi.

- McGowan, ‘The Jacobean Commissions of Enquiry’, pp. xvii-xx.

- Appleby, ‘Pirates and Communities’, p. 155.

- TNA, ‘Examinations of pirates and other criminals’, HCA 1/51/f1r-2v.

- TNA, HCA 1/51/fo. 3r.

- E. Hubbard, Englishmen at Sea: Labor and the Nation at the Dawn of Empire, 1570-1630 (Yale University Press, 2021), p. 12.

Pingback: Global Maritime History Guest Post- Lou Roper - Global Maritime History