Though British warships relied on a constant supply of slops and other items from Britain, these ships could themselves act as make-shift tenders, bringing food and clothing to isolated islands and distributing goods as a strategic sign of goodwill. Below are examples of warships acting as slop shops around the world.

Though British warships relied on a constant supply of slops and other items from Britain, these ships could themselves act as make-shift tenders, bringing food and clothing to isolated islands and distributing goods as a strategic sign of goodwill. Below are examples of warships acting as slop shops around the world.

During the French Wars, warships relied on visiting posts like Plymouth and Portsmouth, or tenders like HMS Diligent which delivered slops to HMS Victory in 1804. But these warships also acted as slop shops in their own right, with their large stores of clothing and their frequent visits to remote ports and blockaded islands. In this reversal of their relationship with clothing in port, captains and pursers had to occasionally manage local demand for clothing that was sometimes strategically expedient to satisfy. Commanders wrote to the Admiralty about these sales, usually because they hoped the Admiralty would cover the charges. To this end, they argued that selling or gifting clothing either revealed an important gap in British strategic considerations or the potential demand of British manufactured goods in foreign markets.

In 1795, Captain Joseph Ellison of HMS Standard wrote to the Admiralty that his purser had been refused credit for some slops he provided to the inhabitants of the small French island Hoedic, which is situated off the south-west coast of Britany. The blockade against the French isolated these islands, meaning that local inhabitants depended on supplies from the British navy, British merchants, or any gutsy French smugglers who risked running the blockade. Ellison assured the Admiralty on his purser’s behalf that the residents of the island were “loyal” but also “distressed”.1 Because this letter only survives as a digest entry, however, any other appeals Ellison made have been lost. Still, the Admiralty wrote that though they referred the letter to the Secretary of State, they could not allow the charges to fall on the navy or the public, meaning that Ellison’s purser was forced to shoulder the cost.

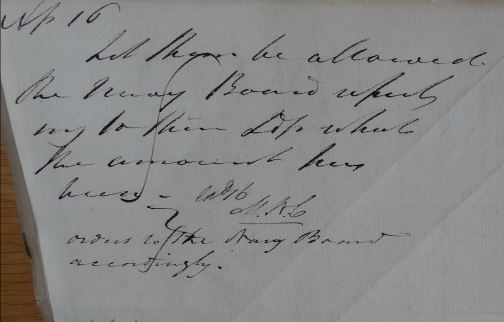

“Ap[ril] 16: Let them be allowed. The Navy Board reporting to their Lords what the amount has been. En[close]d 16 J.W. C[roker] Orders to the Navy Board accordingly.” The Admiralty, after receiving the amount from the Navy Board, orders them to accept Cochrane’s charges. The National Archives, ADM 1/508 f. 107, Minute, March 13, 1815.

In a very different part of the world, Captain George Vancouver sent a letter in 1795 which included thoughts about his recent visits to the Hawai’ian Islands where he encountered British seamen who had settled there with the locals. He observed that these British immigrants would hopefully learn the language and be able to act as translators between any other British arrivals and the local Hawai’ians. He continued that “[I] supplied them with sundry slops clothes … as also a few articles supplied to the Sandwich Islanders who were carried from England & the chief of Orohyhee [Hawai’i].”3 In this case it appears that the Admiralty approved of the charges, hoping that the sailors might eventually prove to be an asset worth their investment, a consideration they did not extend to the residents of Hoedic.

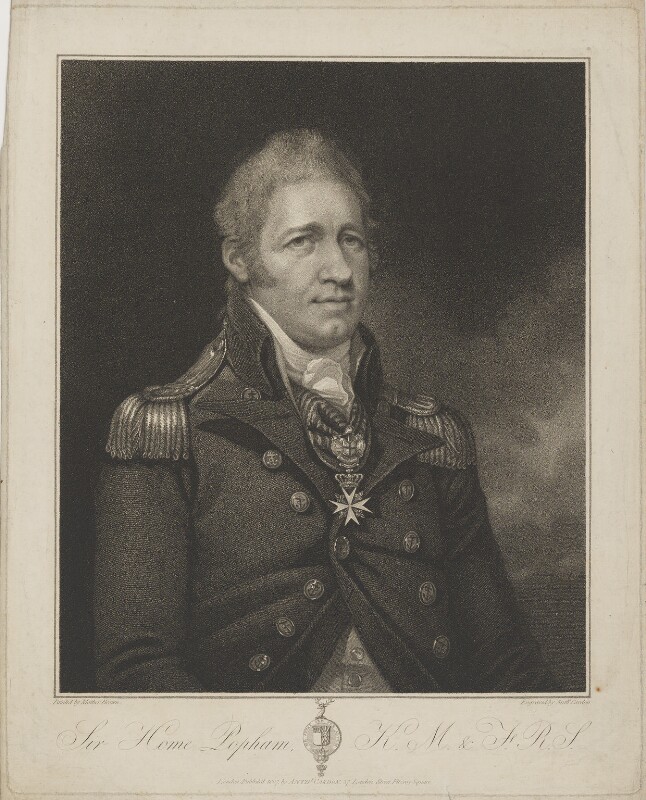

Anthony Cardon, “Sir Home Popham,” stipple engraving, 1807. National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG D40357.

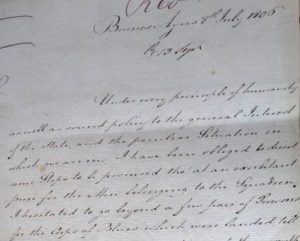

Home Popham, commander of the South Africa station but writing from Buenos Aires, was forced to buy fabric for his sailors. He bought cloth because it was the cheapest way of getting clothing and had the tailors of the squadron make them up. He observed that “al’tho the scarcity of cloth rather presses in one point of view, yet it could be of general benefit to the state, because it offers a much greater market for the exportation of our manufacture.”4 As with Ellison, Popham’s purser was not allowed to waive the charges he incurred buying clothing in Colonial Spain, though Popham tried to appease the Admiralty by making it appear that he had discovered a potential market for British manufactures. Indeed, the Admiralty threatened to charge Popham personally with the slop charges above what he could charge the sailors. Popham spent two more years trying to dodge these expenses.

Closer to home, Captain Graham Moore of HMS Melampus, wrote in his personal journal about his encounters with impoverished Irish in Lough Swilly, a deep fjord on the north coast of Ireland. In July 1796, the residents surrounded his ship with boats, hoping to barter chickens and eggs for clothing. Not able to afford—or refused—clothes from the ship’s slop chest, the ragged Irish instead were willing to take the old clothes worn by the sailors.5 When Melampus returned to the fjord two weeks later, the residents again rowed out to the ship, still hoping for clothing. This time Moore strictly refused their requests to board his vessel and observed that “most of our people would by degrees have parted with all their clothes for a few fowls, potatoes and the itch, which few of the Irish peasantry, that we have seen, are clear of.”6 Though Moore was sympathetic to the poverty of the locals, he neither wanted to risk the illness of his ship’s company nor was he willing to distribute clothing to them from the slop chest.

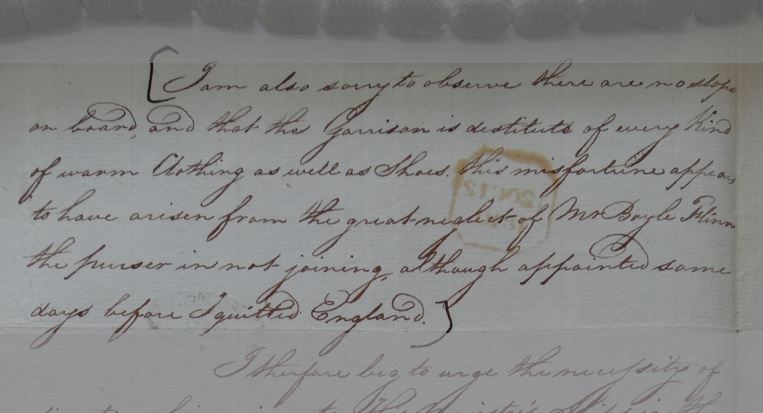

Cpt. Maurice wrote: “I am also sorry to observe there are no slops on board, and that the Garrison is destitute of every kind of warm Clothing as well as Shoes. This misfortune appears to have arisen from the great neglect of Mr. Boyle Flinn the purser in not joining, although appointed some days before I quitted England.” The National Archives, ADM 1/2164 f. 377, October 3, 1810.

Finally, Royal Marines who were tasked with occupying small, strategic islands during this conflict, required consistent supply to support their isolated and distant positions. One example of this is the 1807 to 1812 occupation of the Danish island Anholt, which as significantly positioned in the middle of the Kattegat, the “cat’s hole” between Sweden and Denmark. This was a shallow and treacherous sea that required careful navigation and the Royal Marines occupied Anholt to control and fortify the island’s lighthouse, in addition to considerations about protecting Baltic trade during the gunboat wars.7 In 1810, Captain James Wilkes Maurice wrote to the Admiralty, remarking that: “the Light House on this Island is in a deplorable state for want of Glass … I therefore beg to point out the necessity of a quantity of Glass fit for a Light House to be sent us without loss of time … we are also in great want of a good glazier.”8 Maurice continued that:

that Garrison is destitute of every kind of warm Clothing as well as Shoes. This misfortune appears to have arisen from the great neglect of Mr. Boyle Flinn the purser in not joining, although appointed some days before I quitted England.9

Maurice hoped that ships on their way to the Baltic station might be made to bring out additional slops to supply his 350 marines, or to surrender any slops they could space for his needy garrison.

Supplying ships was already difficult, but ships themselves sometimes had to provide goods like clothing to distant islands, garrisons, and also people who might provide some future strategic value. This could work in the Admiralty’s favour in the case of Hawai’i, where Britain hoped to create demand for British manufactures and to support British settlement. Other times, the Admiralty did not see the benefit of these exchanges, as in the case at Hoedic or in Ireland. Popham tried to use his “market research” in South America to convince the Admiralty to overlook his expenses; they did so begrudgingly, but Popham was additionally awarded by the City of London for opening new markets abroad. Officers of isolated garrisons, like Anholt, wrote to the Admiralty hoping to divert supplies to their important but delicate positions. Warships, therefore, did not just act as purely military vessels but also disseminated a very specific British culture of mass-produced clothing products and foodstuffs into regions and to peoples who might not otherwise come into contact with these products.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

The National Archives, Kew: Admiralty In-letters, ADM 1, 1660-1976.

The National Archives, Kew: Admiralty In-letter Digests and Indexes, ADM 12, 1660-1974.

Secondary Sources

Robson, Martin L. “The Royal Marines Capture, Fortification and Defence of Anholt Island 1807-1812,” The Mariner’s Mirror 105, no. 4 (2019): 407-424.

Wareham, Tom. Frigate Commander. Barnsley, Yorks: Pen and Sword, 2004.

Citations

- Adm 12/67 tab. 94.3, December 20, 1795, The National Archives, Kew [TNA].

- Adm 1/508 f. 107, March 13, 1815, TNA.

- Adm 12/67 tab. 94.3, December 19, 1795, TNA.

- Adm 1/58 f. 60, July 8, 1806, TNA.

- Tom Wareham, Frigate Commander (Barnsley, Yorks: Pen and Sword, 2004), 158.

- Quoted in Wareham, Frigate Commander, 160.

- Martin L. Robson, “The Royal Marines Capture, Fortification and Defence of Anholt Island 1807-1812,” The Mariner’s Mirror 105, no. 4 (November 2019): 409.

- ADM 1/2164 f. 377, October 3, 1810, TNA.

- ADM 1/2164 f. 377, October 3, 1810, TNA.

Refreshing.