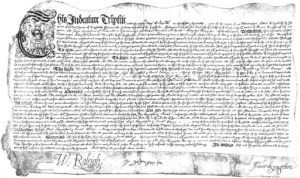

20 Mar 1623 J Williams and R Williams Wine License. Credit The National Archives UK. RN E 351/3157.

A late 16th century Englishman and cleric, William Harrison of Essex, described English drinking, “Likewise in some private Gentlemens houses, and with some Captaines and Souldiers, and with the vulgar sort of Citizens and Artisans, large and intemperate drinking is used; but in general the greater and better part of the English, hold all excesse blameworthy, and drunkennesse a reprochfull vice. Clownes and vulgar men onely use large drinking of Beere or Ale, how much soever it is esteemed excellent drinke even among strangers, but Gentlemen [‘carouse’?] onely in Wine, with which many mixe sugar, which I never observed in any other place or Kingdome, to be used for that purpose. And because the taste of the English is thus delighted with sweetenesse, the Wines in Tavernes, (for I speake not of Merchants or Gentlemens Cellars) are commonly mixed at the filling thereof, to make them pleasant.”1

Besides water, everyone drank ale. From the mid sixteenth century until the nineteenth, English alcohol “production privately and not for sale was important, by individual households, on farms and at country houses and by institutions such as monasteries, schools, Oxbridge colleges, hospitals, asylums, workhouses and the military”2 While many people brewed ale or made wine, in retail establishments, the inn almost always sold ale and sometimes wine but it was the English tavern that always sold wine. Ale houses and tippling houses (places where unauthorized illegal alcohol sales occurred) sometimes sold both but usually just ale.3 During the early English kingdom these establishments were not licensed until the late medieval era (Jennings 2017, 187).

Spreadsheet of Pertinent TNA Wine Licenses E 351 3100 Series

In 1552 the first ever licensing law was enacted but it did not apply to taverns or wine shops. There weren’t many taverns in existence yet and because they were viewed as “unwholesome places” they were typically located on back streets in towns. “All taverns outside borough or town limits were suppressed and were limited to two in a small town or per ratio of the population” (Guthrig 2010, n.p.). The first act pertaining to wine passed in 1553. It attempted to restrict wine prices, placing victuallers (retailers of food and drink) in a wage-losing position when grape prices fluctuated. It also attempted to restrict where wine sales were allowed, and it set a limit lowering the number of retailers to two per town. London already had 300 taverns but the 1553 Act only allowed London forty. The impracticability of this law caused it to be revoked almost immediately causing confusion. Yet, in 1554 Queen Mary issued wine licenses to individual wine sellers by letters patent under the royal prerogative. As such, they began to worry. Out of an abundance of caution some tavern owners obtained multiple licenses when licenses were actually not required. The Worshipful Company of Vintners, the professional wine sellers’ affiliation, was of no help in the matter. In fact, at this time it was issuing unnecessary licenses.4

The distinction should be made that while “…overall, government efforts to promote more vigorous action by justices were ‘at best spasmodic’ before 1600 and local initiatives continued to be taken. The legislation on taverns does not appear to have been effective as the survey of drinking places in 1577 listed more than the permitted number. Moreover, the Crown retained the power to grant wine licences, and freedom of the Vintners’ Company of London also conferred the privilege of retailing wine” (Jennings 2017, 188).

Licensing laws continued to be enacted but also continued to either be revoked or not enforced. It was Elizabeth I (1558 – 1603) who issued a new patent granted to courtiers, but like Queen Mary, also by royal prerogative. Upon receiving it the grantee was responsible for licensing tavern owners, vintners, and wine merchants, allowing the retailers to legally sell wine. Each license holder paid an annual fee. Crucially to the Commonwealth, these licenses were a new form of royal revenue and that was different. This new form of income was regularly collected from during Elizabeth I’s reign (1558 – 1603) through George II’s (1727 – 1760). Elizabeth granted the patents “…to one or more persons in survivorship, normally to trade within their town of residence. Most early licence holders were vintners, but in later years, yeomen, gentlemen, merchants and various tradesmen occur.”5 Receiving this wine license patent was a boon; it was a monopoly: only one person held the patent to grant wine licenses within a specified geographic area at a time.

The Great Seal of Elizabeth I. Credit The National Archives UK CN_13_N3.

Issuing monopolies at royal will, in order to collect revenue for the Commonwealth, was an early form of tax collection called farming revenues or, in this case, the farming of wine licenses. “…the traditional practice was to accept a lump sum or fixed rent from an individual, group, syndicate, or corporate body, leaving the task of collection to them, with the incentive of profit. … Thus, by arrangement and prescription, the crown became assured of a conventional revenue from taxes on property and trade or, more usually, from the farming thereof.”6

New revenue was needed to pay for a naval war with Spain, but Elizabeth I’s use of the royal prerogative to distribute monopolies would later become unpopular and lead to a now well known and crucial moment in her reign. “Sixteenth century England, emerging from feudalism, hesitated on the brink of royal absolutism – and turned away. … On the whole, its people were able to pursue their occupations without political interruptions; and this was perhaps the most basic of the advantages England had in its economic development over the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.”7

Though under Elizabeth the English economy grew, so did prices,8 which may explain why the rate of annual English wine imports by the end of Elizabeth’s reign (mostly from France), at about 8,000 tons, was not much different from those of 1509 – 1546 (during Henry VIII’s reign), at approximately 10,000 tons annually. Annual English wine imports hardly changed during these one hundred years.9

The first person to receive a patent farm license from Elizabeth was Sir Edward Horsey. A privateer during most of his life, when first receiving the grant Horsey was then the Governor of the Isle of Wight. Earlier in his life he had gained prominence by seizing Spanish galleons in the Channel and sailing them and their cargo back home to England as prize. After, Horsey assisted Sir Francis Drake by lending Drake his ship while Drake took refuge in Central America. That Horsey, the first recipient of this new patent was by the time Elizabeth ascended the throne, one of her favorites10, would become a concern for the English public.

Horsey’s patent authorized him to grant wine licenses in “York, Coventry, Exeter, Norwich, Bristol, Kingston upon Hull, Ipswich, Southampton, Sandwich, Harwich, Colchester, Worcester, Leicester, Brightlingsea, Greenwich,… and additional taverns in London, Westminster, Chester and Oxford, together with new ones in every thoroughfare, clothing town, haven town and fisher town were permitted in 1576” (TNA. Discovery. C. Chancery: Wine Licences. Catalog Description. Administrative/biographical background available at https://discovery.nationalarchives.org.uk/details/r/C3770 ).

One of the original licenses he issued is held today in The Lavington Estate Archives. “License. Sir Edward Horsey, kt., Captain of the Isle of Wight, to Francis Garton of Arundel, gent. Letters Patent, dated at Gorhambury, co. Herts., 21 July 1576, giving the said Sir Edward Horsey the right to grant licences for taverns. Horsey grants a licence to the said Francis Garton to keep a tavern or wine cellar in his mansion house at Arundel provided ‘that if French Wines Gascoigne Gwyon Rochell and such like maye be bought for Eleavin poundes the Tonne or under that then the saide wines… not to be souled above xvjd [sic. £0 s.1 d.4 or ‘1 shilling 4 pence’] the gallon And Secke malmeseis and all other swete wines saving Muskadell to be bought at Eight poundes the Butt or pipe [sic. weight measurements that were not yet uniform across the Commonwealth] or under not to be sould above ijs. [sic. £0 s.2 d.0 or ‘2 shillings’] the gallon And muskadell only to be sould to his [Garton’s]… moste proffit'”(TNA. Discovery. LAVINGTON/152. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/fe4392b1-91f8-48b0-87d7-6f16d624057a Accessed 13 November 2019).

While it is generally accepted that Sir Edward Horsey received the first wine license in 1570 (John O’Brien in States of Intoxication, TNA’s website’s catalogue, Discovery’s description of record C 238, Chancery Wine Licences and others), it appears that the year 1570 is taken from a record from Chancery, the seventeenth century English court that dealt with equity, a separate court from common law courts. Yet, it is worth noting that a record dated 26 Sept. 1566-25 Dec. 1571 from another Elizabethan government office, Exchequer, Pipe office, pre-dates the frequently referenced 1570 record and is a wine license, but is listed as having belonged to “Sir E. Horsley”(TNA Discovery. E 351/3153. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C3529158 Accessed 14 November 2019). It is likely that this was simply a misspelling or mistranscription. As of the 1566 record, there is no other known wine license issued by Queen Elizabeth I at the time, and the date of this Horsley record pre-dates but is within a few years of and includes the accepted date, 1570.

In practice, the 26 Sept. 1566-25 Dec. 1571 Pipe Office record, a declared account, would have been read out loud in the office of Exchequer (treasury) from its original parchment copy in front of Sir Horsey and at least one of the queen’s auditors in order to settle Horsey’s account for the year, the way the royal revenue was then collected. After he would have paid his accounts, using the money he had made issuing licenses.

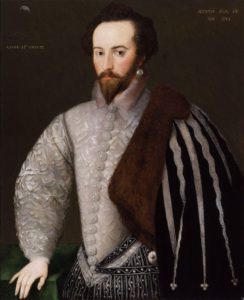

Sir Walter Raleigh 1588 Credit National Portrait Gallery London

It was not to last. Horsey was suspected of skimming and “Abuses of these patents were alleged and in 1583 Sir Walter Raleigh received a new grant replacing Horsey’s. It empowered him to approve Horsey’s licences, replace those that were defective, and complete the number allowed, for a period of 21 years. Horsey had received only half of the fines imposed for breach of the licencing regulations, but Raleigh was granted an annual fee from each licencee as additional revenue. Raleigh leased his patent to Richard Brown; then alleging abuse of it, surrendered it and received another in 1588, this time for 31 years. He surrendered this in 1602” (TNA. Discovery. C. Chancery: Wine Licences. Catalog Description. Administrative/biographical background available at https://discovery.nationalarchives.org.uk/details/r/C3770 ).

First Wine License Granted to Sir Walter Raleigh. Credit the Devonshire Association.

Further, using the royal prerogative to distribute monopolies, and specifically wine license monopolies, had become very unpopular with the public. A “…campaign against monopolies in the 1601 Parliament was mounted by lawyers in the Commons who produced precedents dating back to the reign of Edward III when a licence for sweet wines had been repealed by Parliament. …Despite the stalling tactics of privy councillors in the Lower House such as Robert Cecil the ensuing debate dominated proceedings for almost a week. Numerous Members brought in evidence that the ‘principallest commodityes … are ingrossed into the handes of these bloodsuckers of the commonwealth’, and attacked monopolies as ‘the whirlepoole of the prince’s profittes’. …With tension running high within and beyond Parliament Elizabeth eventually decided to revoke some patents and allow others to be put on trial in common law courts; a Proclamation to this effect was issued before the end of the session. …The queen’s famous ‘golden speech’ on monopolies to a delegation of around 140 Members was a master stroke that defused an ugly impasse and made her seem generous without, in fact, conceding a great deal. At the same time as admitting that some of her grants had been a ‘lapse of error’ she maintained her prerogative, asserting that ‘yt is lawefull for our kingly state to grant guiftes of sundrie sorts of whome we make election’.”11

Elizabeth I, before parliament. Copyright The Trusteets of the British Museum. MN 1858 0417.282.

Among Lord Bagot’s papers, a record dated one month before Elizabeth died, is the copy of an order, probably clarifying wine license holders’ statuses after Raleigh surrendered his licensing grant, “1603. Feb. 21. Order that all not licensed under the Great Seal, or the seal of Sir W. Raleigh, shall forbear drawing and selling of wine; and all others licensed shall repair to John Shelbourne, Her Majesty’s officer, at his house over against Durham Place, near Charing Cross, as they were wont to do, when they are to pay arrears, and receive further order and directions.”12

By the end of Elizabeth I’s reign, material wealth grew in England and Wales even though during the same time poverty increased. “Between 1566 and 1641 the national income of England and Wales more than doubled and since the 1530’s had possibly quadrupled. Towns expanded and the urban population grew both absolutely and proportionately. The ‘middle sort of people’, comprising prosperous manufacturers, independent tradesmen, those in commerce, law and other professional services, as well as substantial commercial farmers, did well. There was thus an expanding market for food and drink. The …expansion of the retail sector in drink… support[s] this view of growth” (Jennings 2017, 12).

The annual fee or personal income Elizabeth granted Sir Walter Raleigh was not allowed by subsequent monarchs, and in fact, during King James I an act was passed in 1623 that made private gain from wine licenses illegal (Hunter 2002, 71-72).

© 2019 Arlene Spencer. All Rights Reserved.

- Harrison, William. 1908. Harrison’s Description of England in Shakespeare’s youth. Being the second and third books of his Description of Britaine and England. Ed. from the first two editions of Holinshed’s Chronicle, A. D. 1577, 1587, by Frederick J. Furnivall, 277-278. London: Chatto & Windus.

- Jennings, Paul. 2017. A History of Drink and the English, 1500-2000. London and New York: Routledge, 38.

- Guthrig, Sylvia. 2010. Inns, Taverns & Alehouses. Exeter: Devon Family History Society. n.p..

- Hunter, Judith. 2002. “English Inns, Taverns, Alehouses and Brandy Shops: The Legislative Framework, 1495-1797.” In The World of the Tavern, Edited by Beat Kümin and B. Ann Tlusty, 71. London and New York: Routledge.

- The National Archives of the UK (TNA) website: Discovery: C – Records created, acquired, and inherited by Chancery, and also of the Wardrobe, Royal Household, Exchequer and various commissions, 1583-1602, Description at https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C3770 (accessed 30 October 2019).

- Crews, C.C. 1936.”The last period of the great farm of the English customs.” Historical Research November 14 (41): 118.

- Davis, Ralph. 1973. The Rise of the Atlantic Economies. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 209-211.

- Elton, G.R. 1955. England Under the Tudors. Oxon: Routledge Classics 2019, 232.

- Stephens, W.B. “English Wine Imports c. 1603-40, with Special Reference to the Devon Ports”. 1992. Tudor and Stuart Devon Edited by Todd Gray with Margery Rowe and Audrey Erskine. Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 141 – 143.

- James, Rev. E. Boucher. 1896. Letters Archaeological and Historical Relating to the Isle of Wight Vol. I. London: Henry Frowde, 544.

- The History of Parliament. Monopolies in Elizabethan Parliaments. https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/periods/tudors/monopolies-elizabethan-parliaments Accessed November 2, 2019.

- TNA: Historical Manuscripts Commission (HMC). 1874. Fourth Report, Part I Report and Appendix. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 331.