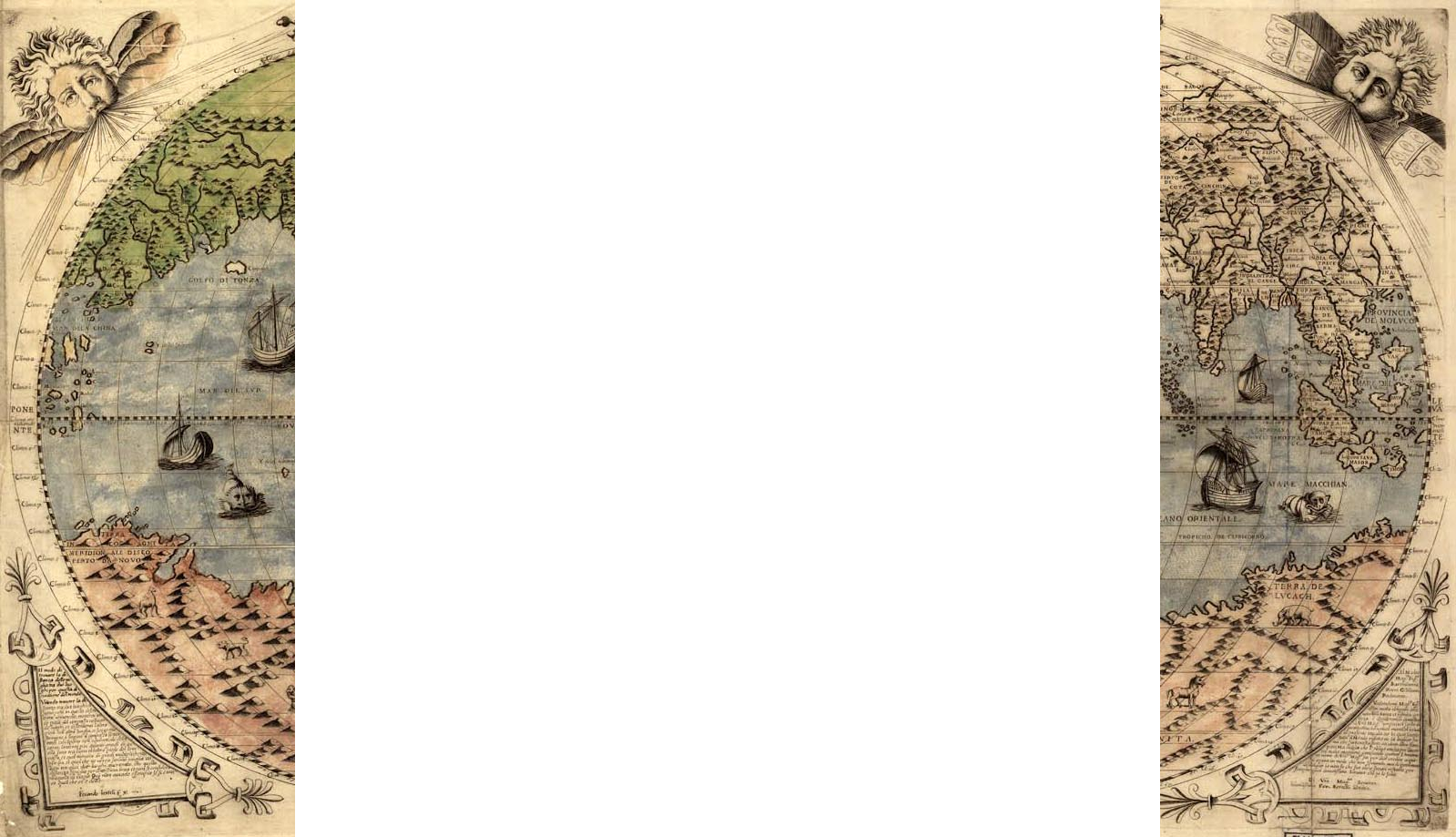

HMS AFRIDI (FL 231) Underway, coastal waters, main armament trained on port beam. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205120057

We’re continuing with Dr Alex Clarke’s series on the Tribal Class destroyers. In this article, he discusses HMS Afridi. To quote the author, ‘HMS Afridi is not the most famous of them, and she certainly didn’t have the longest war – but she was the first of the class, she was the vessel which set the tone for all that followed. She was the leader of the pack, and in her service there was most certainly glory’

“…commanding a Tribal was like owning a Rolls-Royce. No other ship would be quite the same.”i

The Tribal class were only really just coming into service before WWII began, the 1935 batch mostly commissioning in 1938, and the 1936 batch commissioning before the end of March 1939. However, even as they were commissioning, finding their feet; the Tribals were already making a good name for themselves, and in fact even before World War II, the Tribals still managed to get involved in action.

The action of course was mostly to be found in the Mediterranean Fleet’s area of operations, as a consequence of the Spanish Civil War, and thanks to the Mussolini lead Italy, never looking that trustworthy to the RN.ii It was therefore unsurprising, considering the Mediterranean Fleet’s shortage of cruisers to find that the 1st Tribal Flotilla was deployed there; originally named the 1st Tribal Destroyer Flotilla, but by May 1939 this formation had become the 4th Destroyer Flotilla (4DF).iii HMS Afridi was the Flotilla Leader, having passed her acceptance trials on April 29th 1938 (she was commissioned on the 3rd May, completed trials and storing, she had arrived in Malta on 3rd June 1938 – exactly 5 weeks after commissioning to take up her duties. iv)

The 4th July 1938 for her crew was of course not Independence day, but it was still special, as it was the day Afridi left Malta on her first patrol of the Spanish Mediterranean Coast.v Her ‘B’ turret bedecked in broad red, white and blue bands that would hopefully identify her to any would be attackers as British, and therefore neutral.vi During this trip Afridi visited Palma, Barcelona, Marseilles, Gandia and Alperello; carrying out a solo cruise of what was an extensive and at time problematic area. After such solitary duty, when she returned she was immediately thrust to the fore of Mediterranean fleet works, with Rear-Admiral Tovey (Admiral of Destroyers, Mediterranean 1938) embarking on her for the trip to the Ionian Sea where destroyer exercises were scheduled – no doubt him taking the opportunity to familiarise himself with his newest ship.vii This was also an opportunity for the Royal Navy to show off to the Italians, in their ‘back yard’, the quality and capability of the RN’s destroyer force – such an exercises were, as today, often used as a sort of deterrent; on a ‘this is what we can do, don’t make us do it to you’ sort of theory.

Returning to Malta by the 14th September, Afridi met up with her newly commissioned sister ship HMS Cossack, and the then eleven year old County class heavy cruiser HMS Devonshire, off Delos on the 18th September with the intention of embarking on a Black Sea cruise.viii Despite arriving in Istanbul on the 19th September, they had just two days before due to the Czechoslovakian Crisis they were recalled to Alexandria as the RN prepared for war.ix This crisis passed, and with it the two Tribal class destroyers returned to Malta, where Afridi was dry docked.x This is all illustrative of the Tribal class’s peacetime duties, despite having been in commission just seven months, she had conducted what was in effect a war patrol, sailed the length and breadth of the Mediterranean, entered the Black Sea, taken part in major fleet exercises,and visited dozens of ports; by any metric, Afridi had accomplished a lot in to a very short amount of time.xi

Afridi was not alone in doing all this. HMS Cossack, the second of the class, and arguably (due to its war time exploits under Captain Vian) the most famous Tribal class destroyer, was with her.xii Serving as division leader to Afridi’s flotilla leader, her pre-WWII service, especially the first few months were very similar to her older sister’s.xiii There were also differences; it was Cossack’s division (herself, Maori, Zulu and Nubian), which escorted Admiral Cunningham travelling aboard HMS Warspite when he made a goodwill visit to Istanbul (the second visit to the city forCossack) in early August 1939.xiv This was a key part of the Tribal utility, their size, their armaments, their sweeping design, all served to make them psychologically impressive; alongside the refitted and updated Warspite, this was a very daunting force – its intention to impress the Turk’s to not mirror the Ottoman Empire should any conflict occur. There were though perhaps lighter times, touches of soft power, for example when Cossack acted as an ambulance during August 1938; she had been sent to collect the British consul from Barcelona, but he slipped getting into her whaler, so she had to rush him to hospital in Marseilles, making 30knots for the majority of the passage.xv Such halcyon days though wouldn’t last.

With a pre-war period being so crammed, it unsurprising that HMS Afridi’s 247 days of WWII service was similarly crammed.xvi With such a varied pre-war experience, it is perhaps unsurprising that Afridi started WWII leading her flotilla in Red Sea.xvii Where they had been deployed for commerce protection, principally against submarines, but also surface raiders should they arrive; also as a forward force in case a surge to the Far East was needed or reserve for the Eastern Mediterranean. Principally they were where they could rapidly be got to any theatre they might be needed in; whilst also still fulfilling a vital mission. The 4th DF were in effect therefore covering for both the RN’s lack of cruisers, and also acting primarily in a role which was a secondary capability set (for more information about design/concept, please look at the first paper in this series, HMS Sikh). However, when war began Italy didn’t join in straight away, consequently the expected attacks failed to materialise in the Red Sea, or even in Mediterranean; but the attacks did appear in the North Sea and Atlantic – 4th DF was needed at home.xviii As a result between the 10th and 12th of October the ships of the flotilla departed from Gibraltar, leaving behind the Mediterranean in ones and twos.xix

They gathered again at Scapa Flow the home of their sister flotilla the 6th DF, there they refitted for the northern waters.xx Despite the 4th DF often operating alongside the Home Fleet, after an initial period Afridi’s band were not based with them.xxi Instead of calling Scapa Flow home, 4th DF were mainly based further south at Rosyth, primarily for the escort of East Coast Convoys.xxii Also this allowed them to serve as a sort of forward based reaction force, rather like the battlecruiser force had been when it was based there during the World War I; in theory they were co-located with cruisers, in practice they were the constant as the cruisers were always needed elsewhere urgently.xxiii As the forward based force their key role was scouting (manning often what was termed the A-K line far in front of the main force) for the fleet, a role they were used extensively for, up to and during the Norwegian Campaign especially.xxiv

The Norway campaign was a critical campaign for testing the RN, and especially the Tribal destroyers; this was the campaign where they started to prove their worth and earn their fame. It was during this campaign though that the losses started. HMS Afridi was under the command of Captain Vian (of Cossack fame, when she was lost off the coast of Norway whilst covering the withdrawal of troops from Namsos, on the 3rd May 1940.xxv This was two years exactly after her commissioning.xxvi During this battle the escorts faced what was described in official reports as an “incessant attack” by repeated waves of enemy aircraft.xxvii

In fact it was just as the convoy of transports and escorts reached the safety of the main fleet that a large formation of Junker JU-87 Stuka’s attacked, HMS Afridi was bracketed by two of the dive bombers. They were already turning to starboard when the attack was inbound, so Captain Vian decided to continue the turn; unfortunately both bombs hit, the first in the foremost boiler room causing massive damage and starting a fire, the second took out a lot of the portside just forward of the bridge.xxviii This was too much damage even for a design as strong and sturdy as the Tribal Class to take; and she had to be abandoned. However, Afridi and the 4th DF had succeeded in their mission, the troops had been withdrawn and not a single transport had been lost – like at Dunkirk, at Namsos the Royal Navy had the Army’s back. Even in her end therefore she lived up to example she had set through her service, duty and the mission above all else.

References

i Brice (1971, p.19), this layout of 6 guns was of course very similar to some of the proposals considered when the Tribal class were themselves proposed [ CITATION TNA36 \l 2057 \m TNA351]

ii TNA – ADM 116/3871 (1939), highlights this delicate and complicated situation; however, Brice (1971, p.20), D’Este (1990), Smith (in Critical Conflict, The Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Campaign in 1940, published 2011), and Greene & Massignani (1998), all agree and go into wide detail of the affects of this had on RN and to an extent British Government thinking. Although it wasn’t just the RN, the wider British defence establishment worried about the mediteranean, as shown by the 1928 Air Ministry Report, Air Threat in the Mediterranean (TNA – AIR 2/1457).

iii [CITATION Bri71 \p 11 \l 2057 \m TNA38]

iv [ CITATION TNA403 \l 2057 ]

v Brice (1971, p. 20), a fairly common patrol to be issued with at this time, although considering its requirements, and their capabilities, the Tribal class must have seemed a perfect fit [ CITATION TNA382 \l 2057 ]

vi [CITATION Bri71 \p 20 \m Lyo70 \p 36-7 \l 2057 ]

vii [ CITATION TNA393 \l 2057 ]

viii [CITATION Bri71 \p 20 \l 2057 ]

ix [CITATION Bri71 \p 20 \l 2057 ]

x [CITATION Bri71 \p 21 \l 2057 ]

xi [ CITATION TNA393 \l 2057 \m TNA394]

xii [CITATION Bri71 \p 105 \m Ple08 \p 81-95 \m Car50 \p 165 \m Dan06 \p 116 \l 2057 ]

xiii [ CITATION TNA394 \l 2057 ]

xiv [CITATION Bri71 \p 105 \l 2057 ]

xv [CITATION Bri71 \p 105 \l 2057 ]

xvii [CITATION Bri71 \p 23 \l 2057 \m TNA395]

xviii [CITATION Bri71 \p 23 \l 2057 ]

xix [ CITATION TNA395 \l 2057 \m TNA392 \m TNA396]

xx [CITATION Bri71 \p 24 \m Via60 \p 23 \l 2057 ]

xxi [CITATION TNA395 \m TNA392 \m TNA406 \m TNA408 \m Via60 \p 23 \l 2057 ]

xxii [CITATION Bri71 \p 24 \m Via60 \p 23 \l 2057 ]

xxiii [CITATION Bri71 \p 24 \m Via60 \p 23 \l 2057 ]

xxiv [ CITATION TNA397 \l 2057 \m TNA395 \m TNA392 \m TNA396 \m TNA409 \m TNA4010 \m TNA406 \m Via60 \m Ken42 \m Ken74]

xxv [CITATION TNA404 \m Cre67 \p 75 \m Car50 \p 165 \m Via60 \m Ken74 \p 144 \l 2057 ]

xxvi [CITATION Win86 \p 123 \l 2057 \m TNA406]

xxvii [ CITATION TNA404 \l 2057 ]

xxviii [CITATION Via60 \p 48 \l 2057 ]