Arlene Spencer is just completing research for an historical non-fiction book she is writing about early seventeenth century, English, merchantman Master Richard Williams alias Cornish. She researches history and writes full time from her home in Seattle. For more information about the earliest English settlement fishing and trade stations on Damariscove Island, Maine or Monhegan Island, Maine; early English trade in America; Williams alias Cornish; or her book please follow her on Twitter @pencilnubs. Arlene is also joining the staff here at GlobalMaritimeHistory, so please welcome her!

New Evidence: Was Thomas Weston, Seventeenth Century London Merchant among the First to Sail Fish to Virginia’s Starving Colonists?

Thomas Weston, early seventeenth century London merchant, was by the end of 1623 among the first to ship fish into the Virginia colony. Record of three colonial Virginia court hearings: the first Virginia records we have involving either Weston or his ship, Sparrow, will be considered. These three hearings came to my attention during research for a book I am currently writing about a contemporary of Thomas Weston’s, Richard Williams alias Cornish.

Besides this article, only W.C. Ford, editor for the Massachusetts Historical Society from 1909 to 1929, published anything about the Virginia colony’s court records in which Weston is first recorded. Indeed, a biographer wrote of Weston, that after 1622, “His activities and movements thereafter remain obscure…”1Ford only reprinted two of the three colonial court hearings involving Weston that are referenced in this article. Nothing else has been published about the historical record of Thomas Weston in Virginia.2This article begins to remedy that.

In the historical canon Weston is usually not at all associated with Virginia. In 1619, he was a failing business man who was terrible with money, but he offered a small group of English Leyden Separatists, of all things, financing. Afterward, he signed a contract with the separatists promising them financial support and sailing vessels, including a small leaky ship called Mayflower. These separatists were the Pilgrims who in 1620 sailed aboard the Mayflower and founded Plymouth colony, the first successful English colony in New England, and the second English colony in America to thrive after Virginia.

Most of what we know about Weston is told to us in William Bradford’s firsthand account, ‘Of Plymouth Plantation’.3 4 One of America’s colonial founding fathers, Bradford was a Pilgrim, a Mayflower passenger, and Governor of the Plymouth colony from 1621 to 1657. Others of Weston’s contemporaries, such as Winslow (Good Newes From New England), Pratt (A Declaration of the English People Th First Inhabited New England), and Morton (Mourt’s Relation) wrote about him but none had the personal dealings with Weston that Bradford had. From these seminal works we only learn about Weston during the years 1619 through 1623. These are the years he was involved in the founding of Plymouth and an attempted second colony, Wessagusset. The history of Wessagusset is not recalled in this article, but is fascinating. Each of Weston’s contemporaries, noted above, wrote about it. Since Bradford, we learned almost nothing new about Weston until two findings were published. The first was a series of legal records from Weston’s later years when he lived in Maryland; and the second was Weston’s ancestry and a series of lawsuits in London that are related to his business dealings during his thirties, all of which were illegal. This second article gives us the first insight we have had into how Weston began his career.5(Coldham 1974, 163-172). He started his career as a merchant in his early thirties in London but ten years later became heavily involved in the business of establishing the first colony in New England, Plymouth (Bradford 1898, 127, 142).

Thomas Weston had much loftier goals in mind years before arriving in Virginia with fish to sell. In 1619, the English Scrooby Separatists (by then going on their twelfth year living in Leyden, Holland), first met with a representative of London investors named Thomas Weston, who conveyed his fellow investors’ willingness to finance the Separatists’ colony in the New World. The Separatists sought a new home at Plymouth Colony where they could live and worship according to their beliefs (Bradford 1898, 55). Weston and his fellow investors were interested in Plymouth Colony but more so in New England and her natural resources. In seventeenth century English, “ye” meant “the”, “&c” meant “etc.”, and “yt” meant “that”. Bradford described Weston and London investors’ motivation during the colony’s inception:

“Unto which Mr. Weston, and ye cheefe of them, begane to incline it was best for them to goe, as for other reasons, so cheefly for ye hope of present profite to be made by ye fishing that was found in yt countrie..” (Bradford 1898, 55).

The investors in the Plymouth colony needed to form a company, request a grant of land, and negotiate rights, such as fishing rights. “The typical instrument of English economic expansion overseas at the end of the sixteenth century was the chartered company. These corporations, endowed by the Crown with certain prescribed monopoly rights and possessing extensive influence in Parliament and at court, were created to serve as the spearheads of expansion in a period when the state itself was too weak or too disinterested to take the initiative.”6

Image taken from page 313 of ‘Humour, Wit, & Satire of the Seventeenth Century, collected and illustrated by J. Ashton. L.P’

In 1620, after his meeting in Leyden, Weston and other London investors traveled to Plymouth, England where, through his buy-in of £ 500 he joined West Country merchants, (merchants from the West England counties of Dorset, Somerset, Cornwall, and Devon) and together formed the Council for New England. It became the monarch-authorized company that financed, oversaw, and ran Plymouth Colony. These Council merchants were, like Weston, also interested in New England because of her fisheries. As written in the Council for New England’s own records, these merchants’ primary fishing grounds, Newfoundland, had by 1621”…fayled of late yeeres…”, so, a new fishery was then of particular importance to them.7 8

Though they had heard rumors from mariners of great runs of New England fish, the English in 1620 did not know much about the fisheries off the northeast coast of America. “Not only are there no records regarding correspondence, provisioning, or any other aspect of a New England fishery prior to the first decades of the 17th century, the glorious abundance that New England fishing offered came as a great surprise to the first European explorers. Furthermore, it took a while before the earliest entrepreneurs realized what time of year was best for fishing. …the first English explorers and chroniclers claimed the best fishing season was from March through May and it was not discovered until later in the 1620’s and 1630’s that the fish were biting best during the raw months of January, February, and March.”9

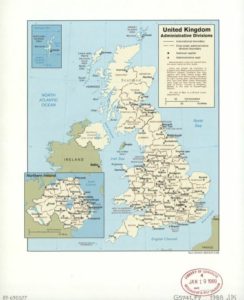

Regions of the United Kingdom. Library of Congress, Digital ID http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g5741f.ct001689

It got the attention of the aristocracy and the powerful in London that the merchant class of the West Country was expanding its market. “English fishing-ships based on West Country ports carried their catch directly from Newfoundland to Spain and brought back specie [sic. coin form of currency], wines, salt and other products to England. With this development the stage was set for prolonged conflict between the West country ports, anxious to develop an expanding dry fishery, and the London chartered companies which sought to organize the trade along monopolistic lines.” (Easterbrook and Aitken, 30).

That Weston invested his own money in a business as an individual along with other investors who together owned a company through joint stock was not new. What was relatively new was this: as individuals, those investors were not necessarily wealthy, courtiers, nor aristocracy anymore. This was a recent emerging economic engine in England: the first of what eventually becomes the middle class. The practice came about because then, in recent prior decades, English merchants had learned from their more affluent and successful Dutch competitors to, as an individual trader, no longer trade solely in one good (i.e. wool cloth, coal, or fish), but to instead diversify trade goods, buying different kinds of goods and then selling those goods by, crucially, creating and maintaining trade routes through relationships with trade partners within Britain and internationally.10

This new middle class or merchant class placed fishing or trade stations on the eastern American coast, tiny though they often were, they were managed and operated by a factor (overseer of trade) who was responsible to their merchant employer back home in England for all trade or truck (barter) transacted by the station. These rudimentary English outposts, though not great in number, were the precursor of the English settlement of New England, particularly existing before the arrival of the Pilgrims. Some were simply rough individual homes built by men who created lasting relationships with neighbor tribes through trade. Others lived in rudimentary stations fishing and processing their catch into dry or salted fish ready for sale after long voyages to markets in America, France, Spain, and Britain. 11

“Early in 1622 Weston, in spite of his large promises, had abandoned the Plymouth settlement…. His finances were failing, and he sought to recoup himself by colonizing on his own account, perhaps by more devious methods. In January he and John Beauchamp sent over the little Sparrow, a ship of thirty tons, to fish and trade. The Sparrow went on to the fishing grounds, but her master sent a boat to Plymouth bearing six or seven men, the advance guard of Weston’s colony of “rude fellows” [sic. Wessagusset].” (Foster 1920, 169).

Image from page 356 of “A short history of England and the British Empire” (1915)

The Julian calendar was used in England during the seventeenth century. The first day of the New Year was not January 1 but the 24th of March. Today, to make it clear to the reader whether the historical date is Old Style (O.S.) or New Style (N.S.) we write Julian dates into a specific format arranged: ‘older O.S. date’, ‘back slash’, modern, N.S., or Gregorian calendar year. For the purposes of this article new style dates are used unless otherwise noted.12

The colonial Virginia court records, written by scriveners or scribes, were written in Secretary , the writing used by the British during the early modern period. Secretary contains many letters we recognize today, but includes holdouts from the medieval era: individual symbols for prefixes and contractions, standardized abbreviations, and in some cases wholly different letters from what we know. It may be helpful to keep this in mind.13

In a portion of a letter Thomas Weston wrote from London, dated January 12, 1621/2, to Governor Bradford at Plymouth Colony, he described a new partnership and the plan for Wessagusset and the Sparrow:

“Beachamp” was John Beauchamp, another London based investor in the Council for New England. Although by this time Weston had quit the Council for New England Beauchamp had not, and so they evidently parted ways. In part of a subsequent letter to Bradford, dated April 10, 1621/2, Weston explained his new business further:

Image from page 359 of “The history of England, from the accession of James the Second” (1914)

After Weston’s “rude fellows’” voyage aboard the Sparrow from London to Damariscove Island (Maine), sailing just under 2,800 nautical miles, (hereafter, nmi.), one of Weston’s contemporaries described that upon their arrival in the New World, “When for instance, the forerunners of Weston’s colony at Wessagusset reached the Damariscove Islands, in the spring of 1622, the first thing they saw was a May-pole, which the men belonging to the ships there had newly set up, “and weare very mery.”14That the fishermen there before Weston’s men arrived had erected a May-pole, used during festive seasonal celebrations and encouraged by King James, but not considered Christian behavior by the Puritans, demonstrates the fundamental differences between sailors or fishermen and the Puritans that made for fraught relations between Plymouth and her rougher less disciplined “rude” English counterparts on nearby coastline and islands, including Weston’s men.

Weston’s attempted second colony, Wessagusset, was meant to be a trade and fishing station. It was located in Massachusetts “nearly opposite the mouth of the Quincy River, and a little if anything north of it… upon the north side of the cove, or indenture of the shore, opposite the mouth of the Quincy River. This cove is unmistakably that now called King’s Cove, formerly known as Hunt’s Hill Cove.”15It is worth noting that others place the historical site of Wessagusset at present day Weymouth. Of Wessagussett, “In 1635 the settlement’s name was changed to Weymouth. While the town was incorporated in 1635, town records began in 1641… The first land division occurred in 1636.”16

To be clear, when she first landed at Damariscove Island, Weston was not yet aboard the Sparrow. He arrived in America for the first time, later in 1622 (Coldham 1974, 167). Of her first American sailing, Bradford wrote the number of passengers the Sparrow carried from Damariscove Island to Plymouth was “A small party, of seven “passengers” but Pratt recalled about ten men, total (Bradford 1898, 137) 17

Sparrow’s 30 tons may seem small by today’s standards too small to cross the Atlantic, but “As late as 1600, the average size of English ships involved in London’s foreign trade was only about 80 tons.”18In a partial national survey taken in 1560, seventy-six ships were included each weighing 100 tons or more. The 1577 survey counted one hundred thirty-five vessels in the 100 tons and upwards range, but six hundred fifty-six ships of between 40 and 100 tons range. But the later survey, the 1582 survey, was the most comprehensive. That year – thirty years before Sparrow’s trans-Atlantic voyage, ships at the 10-80 tons range totaled one thousand two hundred-four ships or 82.8%…” of total ships counted in Britain in 1582 (Friel 2009). It appears from this data that compared to larger ships, at least thirty years before Sparrow sailed the Atlantic, the use of smaller vessels was becoming more common.

After she sailed Weston’s ”rude fellows” from Damariscove Island in 1622 to Bradford’s Plymouth Colony (about 118 nmi.) it is not certain what happened to the Sparrow in the months thereafter. It is most probable that she wound up being used by the Plymouth Pilgrims as a fishing vessel. We do know that she is eventually returned to Weston.

Perhaps the first record of her after Weston’s arrival, Bradford may have described the Sparrow when he wrote that in 1623:

Those who knew Weston noticed in him after this near death experience an end of “his former flourishing condition”. That Weston finally met some of the very dangers in which he placed Plymouth and Wessagusset colonists in may have had a lasting impact. Importantly, Bradford does tell us that Weston recovered “his small ship”.(Bradford 1898, 179). Among the final words Bradford wrote about either Weston or the Sparrow he gives a fascinating description of an event that nearly sank her (a probable second time), through which we learn some details about her design:

To be clear, Weston did not pay his ship’s company but put them on shares, meaning they would divvy up any earnings the voyage made. The ship’s company considered turning pirate but in the end was talked out of it and was very generously given wages by Plymouth Colony. They then sailed the Sparrow to trade with the Narragansett people. It was probably their first voyage to trade with them, because they were not aware of what specifically the Narragansett sought in trade, and so Weston and his ship’s company did not make money on that voyage. It became worse when in a storm they avoided losing the Sparrow by cutting her mast and tackling. Fortunately, they succeeded and they did save her from being driven onto her anchors.

It was these harrowing experiences that brought Weston and the Sparrow to Virginia. In 1623, the last Bradford ever wrote about Weston and his “little ship” was:

Weston and his ship’s company had agreed to sail for Virginia “after they had been to the eastward”, a reference to English deep sea fishing stations to the east of New England in the Atlantic, which included Damariscove Island. It was at one of these stations, Weston and his “rude fellows” either fished, traded for, or purchased a cargo of fish before sailing the Sparrow to Virginia.

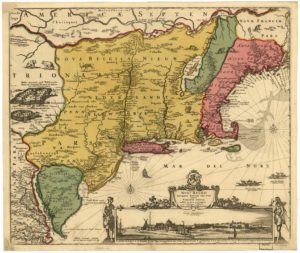

Map of Virginia by Captain John Smith. LIbrary of Congress Digital ID http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3880.ct008919

Around this time, in Virginia, the colonists there were still reeling and recovering from the Great Indian Massacre not quite a year before, on March 22, 1622 N.S. It was the first time there was any violent uprising against Jamestown and it literally caught the colonists off guard. Believing they were on friendly terms with their neighbors, the Powhatan Indians, the Virginia colonists were suddenly and violently set upon inside the colony fortifications. One quarter of the colonists were killed. After the attack, Virginia’s settlers repeatedly conducted military raids against the Powhatans. They were still being conducted into the end of summer 1623 when peace was agreed upon on both sides. It was probably about five months after the last of the retaliatory August raids that Weston first arrived in Virginia.19 20 This citation, of the Minutes of the Council and General Court (hereafter, MCGC) is a part or what remains today of the Virginia colony’s original court records (which today begins in 1622/3, though the colony was founded in 1607). It is an incomplete record. Thomas Jefferson, who rescued the pages, then scattered, pulled back together what he could and saved the collection for posterity. He attempted to place them back into order by date (the first time anyone had done so in one hundred-fifty years). Not until the turn of the twentieth century when it was transcribed from Secretary, by McIlwaine, was it easily accessed. First, it was published as a nearly monthly serial, in issues from April 1911 through October 1923 in the MCGC, The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography (hereafter, VMHB) published by the Virginia Historical Society; and then years later as a book, MCGC of Colonial Virginia.21

It was amid this strife that the first colonial Virginia court record involving Weston or the Sparrow occurs:

Philippe Stubbes, Anatomy of the Abuses in England, pg 32

Howbeck’s testimony, here, refers to “Canada” which not only did not yet exist as a nation, the word had then only recently been recorded for the first time.24It is in Lescarbot’s Histoire de la Nouvelle France (1612) that the word Canada is first used. He described only a region of the St. Lawrence River as being Canada.25 The timing of Lescarbot’s first use of ‘Canada’ dovetails with this record of the use of the word. Too, one of Weston’s sailors gave us a clue. As it is recorded, in his testimony he clarified what the name ‘Canada’ referred to, “…at Dambrells Cove in Canada,…”(McIlwaine 1916, Vol. 24 (4): 343). ]For the purpose of this article, according to these testimonies, I take it a priori that amongst English fishermen, like Weston’s company of seamen and traders, the name, ‘Canada’, during the 1620’s, referred to a geographic region that included Damariscove Island. Today it is located in Boothbay Harbor, Maine, approximately 108 nmi. from Wessagusset. The island has been known by many similar names: Damoralls Cove, Dambrels Cove Island, Dermer’s Island, and others.

This initial court record ends with an incomplete phrase, “It is ord…”. It probably would have read, ‘It is ordered…’ noted when the court gave orders, but there is no record of any orders related to this hearing in the MCGC (McIlwaine 1924, 10).

Besides the Massacre there were other reasons the colonists of Virginia were starving by 1623. Food provisions from England in resupply shipments frequently arrived spoiling and inedible. As well, new colonists often arrived with little to no food provisions for themselves for after their voyage and so required food from depleted stores set aside by the starving colonists.26

Though today we may observe that they could have foraged, raised food, or fished, the colonists of Virginia were a mix of English skilled workers. They were not mostly yeoman who knew how to farm for large numbers of people, nor could they forage for hundreds of settlers. While the colonists had traded with Indians for corn and other food goods, trade had stopped since the Massacre. Though some households kept a kitchen garden, these probably varied in their ability to feed the entire household throughout the year. Few had the resources or time to make butter, cheese, soap, or candles. So, at this time most of these goods were still being imported from England. Food staples were, too. Their situation also had a lot to do with provisioning. Even by 1624 there were hardly any cattle in the colony, yet. That some colonists could have fished for themselves is certain but most would not have had the time. The entire colony was tending full time to tobacco, the only staple crop being raised in large quantities by every Virginia colonist, intended to earn their colony’s investors a profit and the pressure was on. At that time the Virginia investors still had yet to see any profit. Besides, the number of fish needed to feed the colony required skilled labor to catch and then process the fish so it could be stored. Deep sea fishing and processing was not a specialty common amongst these colonists who did not in Virginia, have readily available the ships necessary to be able to fish at sea (Kingsbury 1935 Vol. II, 121, 231).

Image from ‘E Allde Newes From Sea 1606 Ward and Danseker Two Notorious Pyrates’

But some English merchants like Weston did, and Virginia’s situation provided him, already on the eastern seaboard of America, with the opportunity to finally legitimately succeed. From “Canada”, Weston brought into James Cittie (Jamestown) a cargo of salted or dried fish sometime just before January 9, 1623/4 that would feed numbers of people and probably keep for months.

In this, the first colonial Virginia court record we have today that mentions Weston or his ship, Sparrow, we read of his apparent intention to sell or trade fish. To Weston, this business transaction is likely the continuation or a variation of the fishing and trading business that he had planned for Wessagusset before departing England, as he described it to Bradford (Bradford 1898, 138-140, 145-147). This court hearing is perhaps record of the first of Weston’s presence in Virginia, as on this date he evidently had to demonstrate that the Sparrow belonged to him and the fish was his to sell (proof he would not have been required to provide to the Virginia leaders if he was known to them or if he had arrived (to do business in the colony) with an official commission from either the British trade council or the colony’s company, the Virginia Company of London authorizing Weston’s sale of fish). Finally, from the colony’s Governor and Council’s standpoint, that this court record exists at all probably demonstrates that they were ready to do business with Weston (singularly, upon sworn testimony), without official warrant from London, because at that time they were eager to obtain badly needed protein.

John Howbeck, evidentially, was someone who was in a position to be able to verify that the ship and fish were Weston’s (which was apparently good enough for the officials to authorize the sale of fish). Since he could swear an oath to it, in court, it is likely that Howbeck was the purser (the seaman responsible for the lading, shipping, and delivery of the cargo) during that voyage from the fishing station to Virginia. The other man is probably James Carter, Master (a ship’s captain, today). Carter sailed another ship, the Truelove, from England to Virginia at least twice in 1623 (Kingsbury 1935 Vol. IV, 252). That he is a party in this hearing may indicate that Carter was the Master of the Sparrow on her voyage from “Canada” to Virginia. What was being called into question, it seems, is whether or not the Sparrow and the cargo of fish were entirely owned by Weston. As such, it might have been that Carter, as Master, knew that the man named Maunder had a financial stake in the ship or the cargo, or both. Maunder was probably Edward Maunder, a merchant who for a time lived in Virginia (McIlwaine 1919, Vol. 27 (1): 140).

[caption id="attachment_5006" align="alignright" width="300"] Library of Congress, possibly 1624?, found http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3720.ct004901

Library of Congress, possibly 1624?, found http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3720.ct004901

It is perhaps telling that in the MCGC, as it exists today, this first court hearing involving Weston and the Sparrow happens to also be the first in which the commodity, ‘fish’, or the word, ‘Canada’ was used. Wisely, Weston shipped fish into the Virginia colony at a crucial time. We do know that at least five months before Weston’s arrival; other vessels brought cargoes of fish for the Virginia colonists, probably the first to do so. A vessel vaguely described as “a barque”, made two runs from Canada (with fish); the Furtherance arrived “with above 40,000 of that fish which is little inferior to Lyng, for the supply of the colony”; the Samuel; the Ambrose; and “other ships” arrived in Virginia in the summer of 1623. These were ships sent by either the Virginia Company or English merchants.27It appears that no cargoes of fish sailed to Virginia, for the benefit of the colonists, before the summer of 1623. Small personal stores of dried fish were probably sailed from England, Canada, Newfoundland, and European ports as individual deliveries to colonists in Virginia, before this time, but none intended as a colony supply. In other words, Weston was probably among the first merchants to bring a cargo of fish to sell to the starving Virginia colony, and perhaps, too, among the first to bring fish from “Canada”.

The, “other ships” that arrived in Virginia in summer 1623, may have been a reference to the John and Francis, the Adam, and the Tiger each expected with fish from Canada.

In late 1623 O.S. when Weston arrived, the colony’s governor had set prices for certain commodities because, they being scarce, the colonists buying the fish were facing price gouging. For fish from “Newfound-Land” per Hundredweight the price in the Virginia colony was s. 15 in ready money or £ 1 s. 4 in Tobacco which was also used as currency in the Virginia colony. Fish from Canada per Hundredweight was £ 2 in ready money or £ 3 s. 10 in Tobacco (Kingsbury 1935, Vol. IV, 271-273). Since, in the Virginia court record we are not told the amount of fish that was aboard the Sparrow, we cannot estimate the value of Weston’s cargo, but the fixed pricing protected customers while creating a market for Weston and other merchants. This fixed pricing included fish from Canada indicating that at that time it was a common commodity.

The official warrant or commission that Weston apparently did not have before arriving in Virginia with fish to sell to colonists had been issued properly in England, prior to their departures, at different times, to at least four other merchants. These records are important when considering whether Weston was truly among the first merchants to give the Virginia colonists succor, as these are the earliest re-supply commissions specifically for fish for Virginia. Three of the entries are commissions granted the right to fish in New England ‘for the relief of the Virginia colony’. The fourth may or may not have been. The first, in July 1612 was given to a ship sent to fish for the colony but returned to England where sailors filled “the town with ill reports, which will hinder that business…” and never got any fish to Virginia. The second commission, issued in October 1618, was “38. Project of the intended voyage to Virginia by Capt. Andrews and Jacob Braems, merchant, in the Silver Falcon… to fish upon the coast of Canada”.28”But the Silver Falcon never reached Virginia. ‘Near the Bermudas she met with a frigate of the West Indies and had trucke with her.’ exchanging their goods for ‘upwards of 20,000lb weight’ of tobacco.” (Note, too, that the Silver Falcon was only of 10 more tons than Sparrow). Braems returned home to England where some of his voyage’s investors claimed of the Silver Falcon, “she returned ‘richly laden with tobacco, plate, pearls and other rich goods worth some £40,000. They were sure they had been cheated of a huge profit from these glamorous goods…”.29Again, fish never arrived in Virginia. The third entry is November 8, “Commission for Arthur Champernoun, for setting out the Chudley to fish in New England this year.” (Sainsbury 1860, 34). ”In November, 1622, Arthur Champernowne had a commission from the Council for New England permitting his vessel, the Chudleigh, an ancestral name, to trade and fish in the waters of New England. This vessel did not sail, it is likely, before the following spring…”which would be 1623 O.S.30So if Champernowne departed in the spring the Chudley may have been the first to sail fish into Virginia. Champernowne’s sailing may predate everyone’s. Interestingly, a December 19 entry reiterates Champernowne’s commission but crucially adds, “Capt. Squibb to have a similar commission for the John and Francis.” which, as recounted above, arrived in Virginia and then was set out again for Canada to return to with fish. If Champernowne’s commission was indeed “similar” to that of Squibbs, he, too, may have shipped fish from Canada to the relief of the Virginia colonists in early 1623 O.S. I find no record of this. There is a fourth entry pertaining to fishing rights in New England before summer 1623 but importantly pertains to Mr. Thomsen who was set out by the Council for New England in their financial interests only and not to relieve the Virginia Colony (Sainsbury 1860, 34). It appears that the attempts to bring fish “to the relief of Virginia” may have begun in early 1623 O.S. but had at least begun, in small numbers, by late 1623 O.S.

Returning to the first court record, two of the men listed as “present” under the record’s date were Councilmen, leaders of the Virginia Colony that judged and ruled on court proceedings. The third man, Dr. Pott was a freeman of James Cittie. There were two other hearings that day and all three happened to be Admiralty hearings, court hearings specific to the business of sailing (McIlwaine 1911, Vol. XIX (2): 141-142).

In the VMHB McIlwaine transcribed the court record as saying, ‘John Howbeck, aged 35, swore that the Sparrow was Mr. Weston’s and that Weston bought “Becham” out of the ship’. As already stated, McIlwaine adjusted at least one word, “fish”, between his two published transcriptions. Indeed another word in this record changed between the first published transcription and the second. In the second, McIlwaine spelled “Becham” as “Becgam”. The letter ‘g’, may have been transcribed in place of the ‘h,’ in the second transcription, because our modern day letter ‘g’ looks like the Secretary letter ‘h’. McCartney, in her book of biographies of early Virginia colonists follows McIlwaine, by publishing an entry and profile for “Becham” (and “Becgam”) for which the entirety of the biography is taken from this one court hearing. The original handwritten court record online reads as “Bocham” it sounding phonetically like, ‘Beaucham’ or Beauchamp without the ‘p’ sound. (McIlwaine 1911, Vol. XIX (2): 141-142) (McIlwaine 1924, 10)31McCartney makes no mention of Beauchamp.32 Whatever the scrivener may have written, Ford had thought the same thing about this surname (Foster 1920, 170). In a footnote Ford wrote, “Weston is said to have bought Beauchamp out of the Sparrow “before she came from Plymouth.” One Maunder, the purser, laid claim to some interest in her…” Ford did not cite this quote but it appears to be the record of the January 9, 1623/4 Virginia hearing he quoted (Foster 1920, 170). It is helpful to recall that Weston wrote Bradford April 10, 1621/2 about the ship, and included her name, Sparrow (Foster 1920, 145-147). Altogether, the case can be made that it was probably Beauchamp, Weston’s former business partner, discussed in this court hearing and not someone named Becham. In fact, as already stated, Beauchamp was a Plymouth Colony investor who remained invested in Plymouth after Weston left the Council. This might in part at least explain why Weston said in court that he bought the Sparrow and her cargo from him, whatever cargo was sold with the ship.

That it might indeed have been Beauchamp mentioned in this first case is important because it happens that Thomas Weston in fact had not bought the Sparrow, but went into debt to John Beauchamp for her. That debt was still not paid by 1641. “On October 1641 Abraham Halsey of London, gentleman, aged 56, deposed in London that he was a witness to a deed of 29 March 1622 made between Thomas Weston of London, merchant, and John Bewchampe, whereby Weston contracted a debt of £ 486. John Bewchampe, citizen and salter of London, aged 49, deposed at the same time that the debt was still outstanding except for £ 50 “in Cadize and Crewell Ribboning.” Bewchampe had sent his power of attorney to Anthony Jones, merchant and planter in Virginia, “to aske, demand, sue for recovery and residue of the said Thomas Weston.” (Coldham 1974, 167). Weston moved to Maryland in 1640. That Weston moved when he did is interesting timing because a suit was probably filed on Beauchamp’s behalf, in Virginia, apparently in 1640 or 1641, but I have found no record of it.

It is helpful, here, to remember the two 1621/2 letters Weston wrote Bradford and that he wrote them just after he had signed the deed with Beauchamp for the Sparrow, in London, as witnessed by Halsey. The Sparrow was not paid for, though. So, the testimony, as recorded in the initial Virginia hearing, on January 9, 1623/4, was apparently not the truth and the witness probably perjured himself. Too, it is likely that when Weston wrote Bradford that Beauchamp and he went into a partnership, it was not true. Perhaps Beauchamp had simply sold Weston the ship, for a promissory note, and no partnership had ever existed. True or not, to do so might have been strategic. Beauchamp, always remained an investor in the Plymouth Colony even after Weston left the venture, so Weston might have described a partnership with Beauchamp, someone Bradford would have known and trusted, as a means to ensure Weston could expect good relations with Bradford upon his arrival in America.

“Novi Belgii Novaeque Angliae : nec non partis Virginiae tabula multis in locis emendata” Library of Congress Digital ID http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3715.ct000001

The second colonial Virginia court hearing occurs two years after Weston’s initial arrival in Virginia, on February 20th, 1625/6 and also involved a witness (this time Thomas Ramshee, a successful planter in the Virginia colony) who also swore and testified that Weston owned the Sparrow. Once more, a witness for Weston apparently perjured himself. Ramshee also testified that Maunder had, on the initial voyage to America, been her purser but was too poor to properly outfit himself for the voyage and so borrowed money from Weston. At the time of this hearing Maunder was no longer in the Colony but sent notice to Weston that a discrepancy existed in debts between he and Weston. The court did issue an order this time requesting that Mr. John Baynam (likely Weston’s factor in Virginia) bring Weston’s accounting to Weston, after which Weston was supposed to bring the accounting to the court, including goods and debts Baynam received from Maunder. It is not recorded in the MCGC that Baynam delivered Weston’s accounting to him or whether Weston delivered his accounting to the court, as ordered, but from the last of these three colonial Virginia court hearing records we know that indeed he did (McCartney 2007, 589) (McIlwaine 1924, 96).

A year later in court, in James Cittie, on January 11, 1626/7, Thomas Weston, “Merchant”, filed a complaint, which is the last colonial Virginia court record in which the Sparrow is mentioned. He alleged that Bainham (Baynam) had paid James Carter (mentioned in the original hearing) seventy-four pounds of tobacco, which was rightfully Edward Maunder’s (also mentioned in the first case), who was, at this time, in England. Carter was described as master of the Anne (another merchant vessel) who had recently died. Baynam was ordered to re-pay Weston seventy-four pounds of tobacco he (Baynam) had paid to Maunder because the court in its February 20, 1625/6 hearing had, this record says, ordered Maunder to pay Weston and had not given warrant for Baynam to pay Carter. Baynam said that he would pay Weston. It sounds like, in the end, Baynam paid twice. It is interesting to note that in the time in between the first of these three suits, and this one, the cargo in question was fish and tobacco is here being discussed. (McIlwaine 1919, Vol. 27 (1): 39) (McIlwaine 1919, Vol. 27 (2): 140). Tobacco was a form of currency in Virginia. The record does not tell us that payment was made, and we do not read of the Sparrow in court again, so it is likely that it was.

When Weston ran or moved to Maryland he might have taken the Sparrow with him. What is known is that he arrived in Maryland, in 1640, with five people (apparently headrights – passengers that allowed him to obtain land in the Maryland colony in exchange for the expense Weston was to have paid sailing them from England to the New World (if indeed he had)). “At the meeting of the Maryland Assembly, September 5th, 1642, “Mr. Thomas Weston being called pleaded he was no freeman because he had no land nor certain dwelling here &ca. but being put to the question it was voted that he was a Freeman and as such bound to his appearance by himself or proxy whereupon he took place in the house.” of St. George’s Hundred . After, he was made a member of the Maryland Assembly, and obtained a grant the following year for twelve hundred acres, on which he built a manor naming it Westbury Manor. Officially Westbury Manor was eventually deemed a safe haven for neighbor women and children in the event of an Indian attack (Johnston 1896, 201).

“In Bristol [sic. England] on 20 May 1644 William Palmer of that City, sailor, aged 24, deposed that he was one of the company of the barque John of Maryland of which Thomas Weston was the Master. When they had left Virginia at the end of June 1643…” attempting to avoid the violence of the Civil War at home, they intended to land in Ireland but the winds did not allow it, and instead they landed in Cornwall, England in September 1643. “Their 25-ton ship was fully laden with tobacco when it left Virginia but, when the hatches were opened by… the company, it was found to be spoiled because of the leakiness of the vessel during the voyage. The deponent knew that Thomas Weston had not been to London or received any goods from there for five years; he could swear to this because he had been with Weston from November 1638 until they arrived at Padstow[sic. Cornwall].”(Coldham 1974, 167-168).

Weston’s death is recorded as a matter of inheritance. In December 1674 a Richard Norman came before William Hathorn a Massachusetts official and swore, “…that Thomas Weston that used formerly to trade in Virginia and soe to New England and afterwards went home for Bristoll and there dyed as by credible and common report.” After which Weston’s only child, Elizabeth Weston, inherited her father’s land. Elizabeth was raised by a Moses Maverick in Marblehead, Massachusetts. There she married Roger Connant. It is not clear why Weston left a young Elizabeth in Marblehead or with Maverick to raise her (Johnston 1896, 201-203).

Neither Weston’s will nor his grave has been located (Coldham 1974, 168).

Thomas Weston remains an important party in the history of the English colonization of America certainly but, too, he was an example of the first of an emerging middle class evidenced in the first Virginia colonial court hearing in which he was involved. From twice attempting colonization he simply sailed a cargo of fish to Virginia assisting in the colony’s survival, perhaps among the first to assist, thus starting his career as a colony-based merchant. His story is not yet complete. That yet unknown information about him probably exists in archives or repositories is enticing. For example, record of the departures or arrivals of any of Weston’s vessels, including the Sparrow, and perhaps their cargoes, might still exist.

Weston, though he did not always operate within the law or responsibly, eventually achieved legitimacy and success as a merchant. That towards his later years he obtained an official position of civic leadership in Maryland and was granted land demonstrates how capable the merchant class, had become, and how legitimate this merchant, in particular, had become. “His little ship” was a means to that success, perhaps his only means as a shipping merchant, at least for a while. Although we do not know what became of the Sparrow, we at least understand how merchant vessels, including small ones, were critical to the survival of the first successful English colonists and the colonization of America. Perhaps eventually through others’ research we will learn what became of the Sparrow, Weston’s “little ship”.

© 2019 Arlene Spencer. All Rights Reserved.

References

- Coldham, Peter Wilson. 1974. Thomas Weston, Ironmonger of London and America, 1609 – 1647. National Genealogical Society Quarterly. Volume 62 (3): 167.

- Foster, Francis Althorp. January Meeting, 1921. Pickering vs. Weston. Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 54 (1920): 229-232.

- Bradford, William. Bradford’s History of ‘Plimoth Plantation’. 1898. Boston. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/24950/24950-h/24950-h.htm

- See Johnson’s ‘Of Plymouth Plant…’ in which Bradford’s manuscript and letters are arranged into chronological order in which the full text of the Pilgrims’ journals, “A Relation or journal of…” (London 1622) is included. Bradford, William. 2006. Of Plymouth Plantation, edited by Caleb Johnson. Xlibris.com

- Johnston, Christopher. 1896. Thomas Weston and His Family. The New England Historical and Genealogical Register. Vol. 50: 201-206.

- Easterbrook, W.T. and Hugh G.J. Aitken. 1956 (2002). Canadian Economic History. Toronto. University of Toronto Press, 31.

- Christy, Miller, Esq. 1899. Attempts Toward Colonization: The Council for New England and the Merchant Ventures of Bristol, 1621 – 1623. The American Historical Review. Vol. 4 ( 4): 693.

- Mathews, K. 1968. “A History of the West of England-Newfoundland fishery.” PhD diss., University of Oxford, 3.

- Harrington, Faith. 1985. “Sea Tenure in Seventeenth Century New England: Native Americans and Englishmen in the Sphere of Marine Resources.” PhD diss., University of California, Berkley, 44.

- Pope, Peter. 1996. Adventures in the Sack Trade: London Merchants in the Canada and Newfoundland Trades, 1627-1648. The Northern Mariner/Le Marin du nord. Vol. VI (1): 2–4.

- Faulkner, Alaric. 1986. Followup Notes on the 17th Century Cod Fishery at Damariscove Island, Maine. Historical Archaeology, Journal of the Society of Historical Archaeology. Volume 20 (2): 86.

- The National Archives. “Palaeography Quick reference.” http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/palaeography/quick_reference.htm Accessed March 24, 2017.

- Hill, Ronald A. “Interpreting the Symbols and Abbreviations in Seventeenth Century English and American Documents.” 2013. Idaho. https://bcgcertification.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Hill-W141.pdf Accessed January 15, 2017.

- Morton. 1883. The New English Canaan of Thomas Morton, edited by Charles Francis Adams, Jr. Boston. The Prince Society, 17.

- Winthrop, R.C., Jr. 1891. November Meeting, Site of the Wessagusset Settlement. Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Second Series. Vol. 7 (27): 27.

- Chartier, Craig S. 2011. “An Investigation into Weston’s Colony at Wessagusset.”, 13. www.plymoutharch.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/50300822-An-Investigation-into-Weston-s-Colony-at-Wessagussett-Weymouth-Massachusetts.pdf.

- Pratt, Phineas. 1858. A Declaration of the English People Th First Inhabited New England, edited by, Richard Frothingham, Jr., New England Historic Genealogical Society. Boston, 7.

- Friel, Ian. 2009. “Elizabethan Merchant Ships and Shipbuilding.” Presentation. Gresham College. http://www.gresham.ac.uk/lectures-and-events/elizabethan-merchant-ships-and-shipbuilding

- Minutes of the Council and General Court, 1622-1624 edited by, H.R. McIlwaine. 1911. The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Virginia Historical Society. Vol. 19 (2): 115, 147.

- Documents of Sir Francis Wyatt, Governor 1621 – 1626. 1927. The William and Mary Quarterly. Vol. 7 (3): 211–212.

- See McIlwaine’s Prefatory Note explaining in what form the original Virginia colony’s MCGC records exist today. (McIlwaine 1911, Vol. XIX (2): 113-123).

- MCGC of Colonial Virginia edited by, H.R. Mcilwaine. 1924. Richmond. Virginia State Library, 10.

- McIlwaine published transcriptions the MCGC twice. It is interesting to note that in the first published transcription, the VMHB version, the word “fish”, was transcribed as “lists” (McIlwaine 1911, Vol. XIX (2): 141-142). In the original document it does appear to read, ‘fish’. Image 5 of Virginia General Court 1622-29, Hearings, With Minutes, Manuscript/Mixed Material, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/mtj8.064_0002_0573/?sp=5 Accessed January 3, 2019.

- Though not exhaustive, for other MCGC records in which fishermen or traders referred to, ‘Canada’, see: (McIlwaine 1911, Vol. XIX (2): 142); (McIlwaine 1911, Vol. XIX (3): 227); (McIlwaine 1911, Vol. XIX (4): 382); (McIlwaine 1911, Vol. XX (1): 37); etc.

- Elliott, A. Marshall. Origin of the Name ‘Canada’. 1888. Modern Language Notes. Vol. 3 (6): 165. It is interesting to note that during Elliott’s important research into the recording of the first uses of the place name he did not include a review of the MCGC records which repeatedly includes instances of early seventeenth century English sailors’ and merchants’ use of the name, especially given the relatively close geographic proximity of the St. Lawrence River Valley to English trade and fishing stations, like Damariscove Island.

- Kingsbury, Susan Myra. Records of the Virginia Company of London, Vol. II. 1935. Washington D.C. United States Government Printing Office, 174–182, 449, 496.

- Brown, Alexander. The First Republic in America. 1898. Cambridge. The Riverside Press, 516.

- Sainsbury, W. Noël. 1860. Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series, 1574– 1660. London. Longman, Green, Longman, & Roberts, 13, 19.

- Kaufmann, Miranda. Black Tudors. No date. OneWorld Publications. No page numbers.

- Tuttle, Charles Wesley. Capt. Francis Champernowne. 1889. Boston. J. Wilson & Son, 75.

- Image 5 of Virginia General Court 1622-29, Hearings, With Minutes, Manuscript/Mixed Material, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/mtj8.064_0002_0573/?sp=5 Accessed January 3, 2019.

- McCartney, Martha W. Virginia Immigrants and Adventurers 1607-1635. 2007. Second Edition. Baltimore. Genealogical Publishing Company, 123, 403.

Thankyou, you have provided information about my forebear that has been hard to find.

Hi Geoff,

You are most welcome. I am glad that I have helped. Your relative was a fascinating subject to research. Thank you so much for reading and for your comment.

Thankyou,

Thanks for the great article: I only learned about Thomas Weston today when visiting the Mayflower Museum in Plymouth, England. But there are some loose ends that I’d love to hear about: did Thomas Weston ever collect on his investment in the Mayflower, and if so, how much did he collect and how did he actually get them to pay up?

Many thanks for any leads you can provide!

Hi Sooki,

Thank you for your question and for reading. I do not know if Weston ever claimed to have collected on his investment in the Mayflower (great question), but I would argue that he might have indeed claimed that he did because after the Mayflower he returned to Plymouth and soon after began his successful merchant venture in Jamestown – probably his first. Thanks again, Arlene

Thanks for the speedy reply, Arlene – very much appreciated. It’s a good point (that his successful venture in Jamestown might have helped provide some momentum). I’m curious about these early investments because they led to many important developments (many of course involving dubious/regrettable activities) – some of which had clear potential for high returns and some (like the Mayflower) which must have been wildly speculative and/or resonated with the investor’s own sympathies.

With all those great court records that you dug up, I’m wondering whether there are any records of the actual contractual wording between an investor like Weston and a sailing ‘group’ like those aboard the Mayflower? Again, any pointers you could provide would be highly welcome – it doesn’t have to be the actual contractual agreement between Thomas Weston and the Mayflower, of course, (that would be the ultimate find!!) but rather ANY representative example from that era, involving a ‘voyage into the unknown’, from which one could infer a broadly similar wording.

Many thanks again for your time and effort…

You are most welcome! I believe you are seeking the charter party (the contract to sail) between Weston and the owners of the Mayflower. One quarter of the Mayflower was owned by Christopher Jones (who was ship’s Master on her famous voyage). I have not seen any wording but that is not to say it does not exist. I encourage you to read ‘The Mayflower and Her Log’ by Azel Ames. It is available here https://www.gutenberg.org/files/4107/4107-h/4107-h.htm specifically, Chapter III. It gives as detailed an account of the contract as I’ve seen. Hope this is helpful. I wish you the best!

Aha, great link… Will pursue… Many thanks!!

Great link to Azel Ames – thx! (I already wrote this, but here’s a cool p.s. in case that comment duplicates my earlier reply): I just found a *FABULOUS* PBS story from 2015 entitled “What you didn’t know about the Pilgrims: They Had Massive Debt” with some nice quotes and pointers to further research… the article and replay are at the following link:

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/what-you-didnt-know-about-the-pilgrims-they-had-massive-debt

and here’s a representative item with a relevant quote from Weston:

“When the Mayflower sailed home in 1621 without a profitable lading, Weston wrote a sharp criticism to the Governor. He had been informed about how the high death rate and short supplies had weakened the colony during the first dreadful winter, yet he charged the settlers with greater ‘weakness of judgment than weakness of hands. A quarter of the time you spend in discoursing, arguing and consulting would have done much more …’ ” etc etc…

Hope that’s of some use… I’ll sign off here… best of luck with your own research….

Cheers,

-Sooki

Glad to have helped. Thank you, Sooki – best wishes to you, as well!

Dear Ms Spencer: I just ran across your fascinating article on Thomas Weston , above. I am an off-and-on a genealogy hobbyist, and I just found out that I might be descended from him. An early ancestor of mine (great9-grandfather, I think), Walter Bayne of Maryland, d. 1670, married Elinor Weston (d 1701, Maryland). Quite a few secondary sources state that she is the daughter of Thomas Weston, THE Thomas Weston, whose doings you describe above. These are older sources and don’t have primary-source citations, which is frustrating. The writers got this idea from somewhere, though, and I’d like to see some hard proof of the family connection, if it exists.

At this point, you probably know more about TW than anybody else. I’d greatly appreciate any advice, info, etc that you may have. And keep up the good work, btw. I quite like your stuff, even though it’s not a topic that I ordinarily follow.

Hi Mark,

Thank you so much for reading, your encouragement, and for your kind words. I have located a source that may be helpful in your quest.

https://www.colonial-settlers-md-va.us/getperson.php?personID=I002198&tree=tree1

You will see it argues that the Elinor Weston who married Bayne was not a daughter of Thomas Weston’s and the author fully cites their argument. The citations may be secondary sources but I am hopeful that you could confirm with either Maryland State Archives and or the respective counties’ archives.

I hope that this is helpful.

I wish you the very best in your work.

Hi Arlene,

I am just now finding this article. It is so well-sourced; thank you for this work! I wonder if you found anything about John Hansford in your research into Thomas Weston?

In American Antiquarian Society [April, 1930.] New England’s Contributions to Virginia, p. 20, it is stated in an article about Thomas Weston, “According to the Maryland Archives, John Hansford, of York County in Virginia, was appointed by the Maryland Court, his administrator, with the will annexed….” It seems that Weston was a close associate of John Hansford, both being from London, England and also in York Co. VA.

In Massachusetts Historical Society Proceedings, October, 1920 – June, 1921, Volume LIV, in a lawsuit between Edward Pickering and Thomas Weston, it is stated, “Thomas Weston was born about 1585,” and “About 1620 Weston married Elizabeth, the daughter of Christopher Weaver…” It further states that his only surviving child was Elizabeth, born in 1632, who married Roger Conant. Are you familiar with these sources? I am most interested in your thoughts.

I am researching John Hansford and would appreciate any information or guidance you can give me.

Thank you,

Sharron

Hi Sharron,

Thank you so much for reading, for your kind feedback, and for sharing your queries.

If you haven’t yet, I would follow up my citations for Weston’s years in London. I do not off the top remember John Hansford and they may not have had dealings before Virginia but I would look for record of Hansford in merchant trade (i.e. arranging transport for the emigrants in England or in English merchant trade in the Low Countries. I definitely would check not only York County, VA records and their historical merchant references but I would also look for Hansford in Maryland’s Archives, holdings. If the two men were close they may have conducted business together but that might have occurred later in Weston’s life. I am sorry I’m not more help, here.

I am familiar with the quote you cited stating that Elizabeth was Thomas Weston’s only surviving child.

I corresponded with someone else who commented, here, and they were also interested in Weston’s children. I will paste my research findings (from that correspondence) since it may be helpful to you and others.

I begin quoting my prior correspondence here:

You might have heard the account of the More children of Shropshire, England, and their connection to the Mayflower’s 1620 voyage. In case you haven’t, please bear with the following as it explains who Elinor More was and her connection to Thomas Weston.

“Samuel More had married his cousin Katharine in 1611. This marriage had been arranged by the two fathers to consolidate the two estates: Larden in Shipton (about 960 acres) and Linley, near Norbury (about 3000 acres). Whether Katharine and Samuel had any say in the matter is open to question. Samuel of Linley was only 17; Katharine of Larden was 24. It seems an unlikely match but Katharine’s father was keen to settle her with her cousin as he had no sons to inherit Larden: all three had died, the last in a misguided duel over a lover. The marriage contract provided for the two estates to be combined, for Samuel’s father, Richard, to become master of Larden, for Richard to pay Katharine’s father, Jasper, £600 (about £60,000 today), for Jasper and his wife and Samuel and Katharine to live at Larden and, most significantly, for the combined estates to pass to the “heirs of their bodies” of Samuel and Katharine.

“Later, when she was accused of adultery, Katharine declared a pre-contract (betrothal) with a local yeoman farmer, Jacob Blakeway, but she had no witnesses. The declaration of the marriage contract was then deemed to be an admission of the adultery which Katharine did not deny. Samuel had reached the conclusion by the time that Katharine’s fourth child was born (Mary in 1616), that none of her children were his. He thought they looked too much like Jacob Blakeway. Samuel spent most of his time in London as secretary to Edward Zouche, Lord President of the Council of Wales, amongst his several important posts. Jacob was one of Katharine’s father’s tenant farmers.

“In April 1616, Samuel arranged a separation from his wife. Katharine may have moved to stay with relatives in London. The children were sent to live with tenants of his father, near Linley. Katharine sued for an annulment of the marriage because of her pre-contract but, there being no witnesses, she lost the case. Samuel responded with a charge of adultery against Jacob Blakeway. Jacob lost the case and fled in the face of large fines. No more is heard of him. Samuel sued again, this time against Katharine for a judicial separation which gave him control of the children. Katharine’s appeal failed.

“The next steps in this sad story take us back to the Mayflower. Lord Zouche, Samuel’s employer, was a member of the Virginia Company which had been transporting children from London to meet the need for labour in America. Meanwhile, a small band of Puritans (much later to be known as the Pilgrim Fathers), hoped to emigrate to America to gain greater freedom for their religion. A deal was struck: free land for the Puritans in America, £10 share per person to pay for the voyage, unaccompanied children to be looked after by the adults. Samuel paid £80 for double shares for the four children and they were allocated guardians. Ellen (8) was placed with Edward Winslow; Jasper (7) with John Carver; Richard (5) and Mary (4) with William Brewster.” (Virtual Shropshire County, UK. The More Children’s Story. http://shropshiremayflower.com/the-four-more-children/)

Indeed, Bradford wrote, “Mr. Edward Winslow; Elizabeth, his wife; & 2. men servants, caled Georg Sowle and Elias Story; also a litle girle was put to him, caled Ellen, the sister of Richard More.” (Bradford, William. Of Plimouth Plantation. 1898. Appendix 1. Wright and Potter Publishers, Boston Massachusetts, 531. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/24950/24950-h/24950-h.htm#Page_531)

Weston’s role is made clearer if we back up in the story a bit.

“In that same year, by his own account, Samuel went to his employer and a More family friend, Lord Zouche, Lord President of the Council of Wales, Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports and Privy Counselor, to draw up a plan for the disposition of the children.[15] Zouche had been a member of the Virginia Company and in 1617 he invested £100 in an expedition to the Colony of Virginia, which is where the Mayflower was supposed to have landed. It was his actions that were instrumental in putting the More children on the Mayflower.[16][17][18] At that time, children were routinely rounded up from the streets of London or taken from poor families receiving church relief to be used as labourers in the colonies. Any legal objections to the involuntary transportation of the children were over-ridden by the Privy Council, namely, Lord Zouche. Most people thought it a death sentence and, indeed, many did not survive either the voyage or the harsh climate, disease, and scarcity of fresh food for which they were ill-prepared.[19][20]

“Additionally, in 1616, Samuel More, under his father Richard’s direction, removed all four children from Larden and placed them in the care of some of his father’s tenants near Linley.[2][21] The removal was shortly after the youngest child had been baptised, which was on 16 April. According to Samuel’s statement,[22] the reason he sent the children away was “as the apparent likeness & resemblance … to Jacob Blakeway”, quoting from: “A true declaracon of the disposing of the fower children of Katherine More sett downe by Samuell More her husband” together with the “reasons movinge him thereunto accasioned by a peticon” of hers to the Lord Chief Justice of England and it is endorsed, “Katherine Mores Petition to the Lord Chief Justice …the disposing of her children to Virginia dated 1622”.[23] Samuel goes on to state that, during the time the children were with the tenants, Katherine went there and engaged in a struggle to take her children back:[24] “Katharine went to the tenants dwelling where her children had been sequestered, and in a hail of murderous oaths, did teare the cloathes from their backes”. There were at least twelve actions recorded between December 1619 and 8 July 1620, when it was finally dismissed.[25][26]

“The statement details that, soon after the denial of the appeal on 8 July 1620, the children were transported from Shipton to London by a cousin of Samuel More and given into the care of Thomas Weston, “…and delivered to Philemon Powell who was intreated to deliver them to John Carver and Robert Cushman undertakers for the associats [sic] of John Peers [Pierce][21][27] for the plantacon [sic] of Virginia”[28] in whose home they would be staying while awaiting ship boarding.[29][30] Thomas Weston and Philemon Powell were both poor choices, and Thomas Weston especially was quite disreputable. Soon thereafter, Powell would become a convicted smuggler and Weston an enemy of the Crown.[31] As the agent of the Merchant Adventurer investment group that was funding the Puritan voyage, Bradford states that Weston caused them many financial and agreement contract problems, both before and after the Mayflower sailed. Weston’s Puritan contacts for the voyage were John Carver and Robert Cushman who jointly agreed to find the children guardians among the Mayflower passengers. Carver and Cushman were agents from the Puritans to oversee preparations for the voyage[32] with Robert Cushman’s title being Chief Agent, from 1617 until his death in 1625.[33] Within several weeks of the More children’s arrival in London, and without their mother Katherine More’s knowledge or approval, they were placed in the care of others on the Mayflower, bound for New England.[23]

“After the Mayflower sailed, Katherine made another attempt to challenge the decision through the courts. It was this legal action in early 1622 before Chief Justice James Ley which led to the statement from Samuel explaining where he sent the children and why, the historical evidence for Richard More’s early history.[34” (Richard More [Mayflower Passenger]. Wikipedia. Last accessed April 9, 2021.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_More_(Mayflower_passenger)#cite_note-ARW163-168-2) [All links and footnotes, here, are Wikipedia’s]

I use these two sources’ information, here, because they are well cited. The County of Shropshire has the records in their PRO so I am confident about their given account. (If you go to their website, you’ll see that they sell more than a few books specifically about the More Children of Shropshire). I am never eager to use Wikipedia as a citation but I do so, here, because the account is very accurate (of what we know about Weston) and, too, well cited.

I have read that the children were taken to Thomas Weston’s home in Aldgate in London and lived there for weeks before embarking aboard the Mayflower. I cannot verify this. Did she, for some reason, during that three week period call herself Elinor Weston or was thought to be Weston’s daughter during this time by someone else who referred incorrectly to her as Elinor Weston? It is a possibility that she is one and the same person but I have no primary, secondary source to demonstrate or suggest this. This would have to be investigated. The widely accepted historical account is that Elinor More (under Winslow’s care) died aboard the Mayflower, during the voyage, but I am not sure what the documented source of her passing is. If you do not know, either, it would be worth following up.

I located one other child of Thomas Weston’s, a daughter, who I have never seen listed in a family tree or included in any source I’ve read about Weston. We know that Thomas Weston married Elzabeth Weaver. In the Lincolnshire pedigrees register they are listed as married and under them is one offspring, Hestor.( Lincolnshire Pedigrees. Rev. Canon A. R. Maddison, Editor. 1904.The Harleian Society. London, Vol. 3:1047. https://archive.org/details/lincolnshirepedi03madd/page/610/mode/2up?view=theater) I have never seen Hestor Weston on any Thomas Weston family tree.

I looked but I did not find any further record of Hestor Weston at all. Might Hestor have gone by “Elinour” later in life and been your ancestor? Perhaps.

A third possibly could also be kismet – literally just two days ago, a ‘possible daughter’ was added to Thomas Weston’s profile in ‘Early Colonial Settlers of Southern Maryland and Virginia’s Northern Neck Counties’. She would also be someone not noted in Thomas Weston family trees, to my knowledge. She was Mary Weston and a note is included which states,

“Not proved as daughter

Cavaliers and Pioneers, Patent Book No. 4; [Nell Marion Nugent]; Page 324

THOMAS GERRARD, 300 acs. Northumberland Co., 24 Oct. 1655, p. 11, (17). 200 acs. abutting Sly. upon land of Tho. Kedby, Wly. upon a creek issuing out of great Wicocomocoe Riv. &c. 100 acs. Sly. upon land sd. Kedby sold to John Johnson, Wly. upon land sd. Garrard bought of Thomas Watts, Ely. upon land of Mr. James Hawly. 200 acs. granted unto Thomas Watts, Junr., 1 Apr. 1650 & assigned to sd. Gerrard & 100 acs. for trans. of 2 pers: Mary Wesson, Xpr. Peirce” (https://www.colonial-settlers-md-va.us/getperson.php?personID=I072116&tree=tree1)

Given the date of the land transaction I think Mary could have been Thomas Weston’s daughter. I do not know enough about this particular parcel or what land Weston owned or was granted in Virginia to consider this record further, and there were other people named Weston in the Virginia Colony (McCartney Virginia Immigrants and Adventurers). If there is no record of Thomas Weston owning this property she may have been from another Weston or Wesson family. This needs following up, too.

Fourth, and also intriguing – there is an interesting record quoted at the very bottom of Thomas Weston’s profile in the “Early Colonial Settlers of Southern Maryland…”. The very last (of a long list) of legal settlements of Weston’s estate is quoted as “Joane Bennett Land Grant, 1636 – York Co. VA

“Land Office Patents and Grants – Library of Virginia

http://198.17.62.51/cgi-bin/drawer/disk19/CC150/0353/B0110?63

Patents No. 1 p. 346

“Joane Bennett

450 Acres

“To all to whome these prsents shall come I Capt John West Esq. Governr &c send greeting &c Whereas by letters bearing date the 22nd day of July 1634 from &c Now Know yee that I the said Capt John West Esq. doe wth the consent of the Councell of State accordingly give and grannt unto Joane Bennett widow fower hundred and fiftie acres of Land situate lying and being in the Countie of Charles river upon the new Poquoson river East towards the Baye West into the woods North upon the Pinye Swamp & South upon Robert Thresher The said fower hundred fiftie acres of Land being due unto her the said Joane Bennett as followeth (Vizt) [videlicet] fiftie acres for her owne psonall [sic]adventure and fower hundred acres by and for the transportaton at her own pper1 costs and charges of Eight prsons into this Colony whose names are in the records mentioned under this pattent To have and to hold the said fower hundred and fiftie acres of land & to bee held of or [our] Soveraigne Lord the King &c Yeilding and paying unto or said Soveraigne Lord the King &c Provided alwaies that if the said Joane Bennett her Heires or assignes &c Given at James City the 6th day of May 1636 Ut in alij’s

Joane Bennett widd:

Anne Winter Jon Rocto Jon Marshall

Tho: Prewitt Andrew Chant Jon Morris Pole

Carplights”

One may exist, but I have never seen any record of Thomas Weston associated with a Joan Bennett. I believe she is the Joan Bennett who arrived with her husband, Samuel, aboard the Providence, in James Cittie in 1622. They and one other man, William Brown, were servants of William Tiler’s in the Virginia Colony (“Original Lists of Persons of Quality, 1600-1700” by John Camden Hotten, published by Genealogical Publishing Society Co, Inc., 1983, 259. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044010737849&view=1up&seq=283&q1=tiler). McCartney wrote biographies for Samuel and Joan and I’ve attached them to this email for your review. You will see though Samuel dies and Joan remarries it is not to Thomas Weston. So, one wonders why Thomas Weston left her land – was she yet another daughter or someone otherwise significant to him? McCartney only states that the Bennetts had sons so there is no record of Joan having a daughter (and McCartney’s sources are almost all Virginia colony records – there may be records that answer this question, of course, in England). I do not know who her father was. Might Weston and Joan Bennett have had a relationship prior to or after her marrying Samuel and if so, what was it?

Here, I end quoting my prior correspondence and I want to share the same caution I wrote in my correspondence: this research was by no means exhaustive.

You ask for my thoughts. My sense is that Thomas Weston for much of his life sought business opportunities not otherwise afforded to him by birth or status. Certainly by his later years he had been so successful in his dealings that he had amassed wealth. As I understand it most of his business was mariner merchant ventures. All of this bodes well for more/new information to be uncovered about Weston, his business, and his life. I do think it is possible that Weston had more than one child living in 1632.

I hope that I have been helpful. If not, please feel free to contact me through my website with further questions, at arlenespencer dot com

I wish you the very best in your research.

Arlene,

This has been very helpful. Thank you so much!

Sharron

I’m researching my family history in Maryland and came across a rumor that my ancestor, Richard Gardiner, might be connected to the Mayflower passengers. (There was a Richard Gardiner on the Mayflower but no one knows what happened to him or who he was. He was not a Pilgrim some think he was a sailor)

There are a couple of reasons I doubt this:

Richard Gardiner was Catholic, and the Mayflower passengers were Pilgrims (a Protestant sect).

I found information about “Strangers” on the Mayflower, but I’m still unsure if that applies to Richard Gardiner.

Here’s what I do know:

Richard Gardiner was part of the Maryland Assembly.

There are conflicting stories about his fate: some say he returned to England, others say he died in a rebellion. (He also had a son called Richard, I believe)

His children may have fled to Virginia during the rebellion and returned later.

My goal: To find a connection between Richard Gardiner and Weston, Maryland (possibly through the “Weston time” you mentioned).

This connection, if it exists, might strengthen the possibility of a Mayflower link (though still unlikely due to his religion).

I’d appreciate any information you have about Weston, Maryland and its history, particularly during the time period related to Richard Gardiner.

Hi Christa,

I am sorry to say that I have no more information about Weston’s time in Maryland than what I wrote, here. I wish I could help. I encourage you to contact Maryland State Archives, Maryland Center for History and Culture, and Maryland Historical Trust and share your question about a connection between the two men.

Thank you for reading and for your comment. I wish you success in your research. Arlene

Thank you for your research. I was wondering if you know if Weston sailed to Viginia with fish more than once, 1623/1624

Hi Patricia,

Weston was fulfilling a need for food, and then continued to do so, even if the need was no longer dire. The colony was struggling to maintain reliable regular resupply shipments from England. The idea that a volume of affordable food could be obtained for the colonists from nearby probably provided the colony’s leadership with some relief. For Weston, while certainly not the only merchant shipping supplies to James Cittie, he probably helped to form or shore up a more reliable, local supply chain and in doing so started a serious business for himself, and on the western side of the Atlantic. This was an opportunity and Weston took it. Good question! Thank you for reading. Arlene