Thank you to Elizabeth Rynecki for this fantastic guest blog post about her father’s experience doing maritime salvage.Elizabeth Rynecki’s narrative non-fiction memoir, Chasing Portraits: A Great Granddaughter’s Quest for Her Lost Art Legacy was published by NAL/Penguin Random House in 2016 and received a Kirkus Starred Review. She wrote, produced, and appeared in the documentary film, Chasing Portraits (distributed by First Run Features). She’s been featured in the New York Times, been a guest on NPR affiliate stations, and been a speaker at bookstores, libraries, book festivals, and film screenings around the world. Her limited edition, six episode podcast, That Sinking Feeling: Adventures in ADHD and Ship Salvage is available on Apple, Pandora, Spotify, and even YouTube. Elizabeth has a BA in Rhetoric from Bates College and an MA in Rhetoric and Communication from UC Davis. She lives in Oakland, California with her husband, two sons, and three black cats. She can be found at www.ElizabethRynecki.com and at the following social media Threads, BlueSky, Instagram or Substack.

Thank you to Elizabeth Rynecki for this fantastic guest blog post about her father’s experience doing maritime salvage.Elizabeth Rynecki’s narrative non-fiction memoir, Chasing Portraits: A Great Granddaughter’s Quest for Her Lost Art Legacy was published by NAL/Penguin Random House in 2016 and received a Kirkus Starred Review. She wrote, produced, and appeared in the documentary film, Chasing Portraits (distributed by First Run Features). She’s been featured in the New York Times, been a guest on NPR affiliate stations, and been a speaker at bookstores, libraries, book festivals, and film screenings around the world. Her limited edition, six episode podcast, That Sinking Feeling: Adventures in ADHD and Ship Salvage is available on Apple, Pandora, Spotify, and even YouTube. Elizabeth has a BA in Rhetoric from Bates College and an MA in Rhetoric and Communication from UC Davis. She lives in Oakland, California with her husband, two sons, and three black cats. She can be found at www.ElizabethRynecki.com and at the following social media Threads, BlueSky, Instagram or Substack.

My father was a ship salvage engineer for more than 30 years. I’m a writer, a filmmaker, and a podcaster, and so a few years ago, he asked if I might be interested in his files. My curiosity about Dad’s career soon resulted in more than a dozen large, black plastic storage bins scattered across my office. Some hug the edge of the squat bookshelf, others are stacked against an overstuffed filing cabinet. A tenuous path leads from the door to my desk chair where I sit and take stock of the boxes, each adorned with two-inch wide blue tape emblazoned in my Dad’s handwriting with just one word: SALVAGED. His idea of archival indexing leaves something to be desired.

Peeking out of the top of one of the boxes is an orange paper envelope with the phrase, “Here are Your Pictures”, printed on it. On the front of the first envelope, someone has written: Ellora. But there are many others: Mimosa, Mobil Oil, Huichol, Magnificence Venture, SeaTiger, Ocean Ranger. There are thousands of photographs buried in these boxes — photos that belong to what my Dad sometimes calls “ancient history.” Some family photo collections capture birthday parties and beach vacations. My Dad’s collection showcases stranded, damaged, and wrecked ships with names that sound only vaguely familiar — like distant cousins I can’t quite place.

These photos don’t mean much to me, though they document the variety of jobs my Dad worked on over the course of his career as a salvage engineer and consultant. I match a few of the photos to the job summaries in his marketing materials listing several of his more challenging projects, all with successful recoveries: an overturned barge in Khutze Inlet (Canada), a cargo ship sunk at the dock in Palermo (Italy), explosions and a fire at Fort Mifflin Terminal (Philadelphia, PA), an oil spill in San Juan Harbor (Puerto Rico).

Despite the advantage of being his daughter, armed with a lifetime of hearing stories about the jobs, I feel like I’m wandering through a history museum with poorly written exhibit labels. I can read the words, but they don’t explain much. I need a guide. I need help.

Over a Thai lunch, I complain to Dad about not understanding the technical details of his files. I bemoan the fact that my liberal arts education (which I value) has not prepared me for the technical summaries delivered to clients or the mathematical formulas and physics equations that fill the books he wrote for the U.S. Navy Supervisor of Salvage and Diving. “The truth is,” I tell Dad, “I’m lost.”

I poke the pad thai noodles on my plate, embarrassed about the simplicity of what I want to know. I ask anyway, hoping his answer might help guide me in a rewarding direction.

“Which was your biggest job? Most memorable?”

“The Igara,” he says without hesitation. “The complexity of the project, difficulties with the stability and structure, explosive cutters, and blast effect, made it challenging. It was a high-risk job requiring real guts, the work of hundreds of men, and dozens of salvage ships.”

I heard his words, but my thoughts kept wandering. I couldn’t quite put my finger on why, until it hit me. Dad always came into the picture after a disaster. But I wanted to know what happened before. After all, the salvage jobs themselves were just the aftermath—the story began long before the calamity.

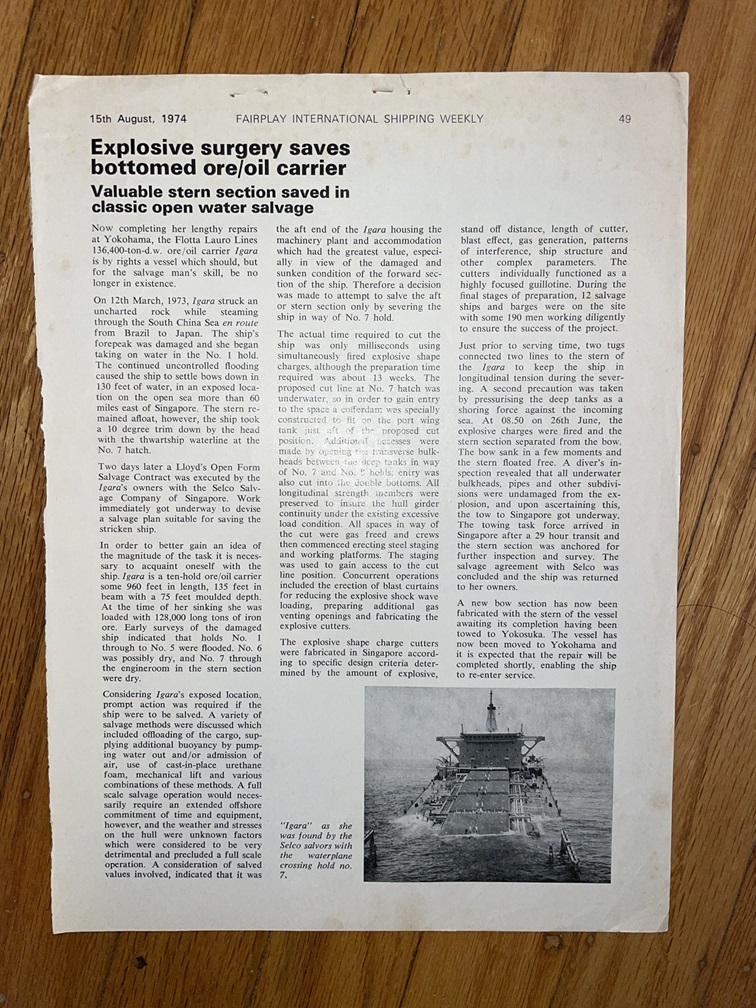

The Igara (with her cargo holds full of more than 100,000 tons of iron ore) departed Port Vitória in southeast Brazil and headed to her destination in Muroran, the port city on the south coast of Japan’s Hokkaidō Island. The best sea route would take the ship east, distance-wise over halfway around the world; first across the Atlantic Ocean, rounding the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa, then across the Indian ocean before turning north and winding through the congested and tricky waters of the Indonesian archipelago. After passing through Sunda Strait, the channel between Java and Sumatra, the Igara headed north through the South China Sea toward Japan. While the vessel followed the same route taken by mariners for centuries, the heavily laden ship not only had cargo holds full of iron ore, but also fuel, fresh water, ballast water, and provisions. In short, the draft of the ship required deep waters.

The deep water and the captain’s luck ran out on an uncharted reef about 190 miles from Horsburgh Lighthouse, a landmark known as the eastern entrance to the Straits of Singapore. The speed and weight of the ship caused severe bottom damage as it ground into and over the reef. Not knowing the extent of the damage, and hoping to get help before things got worse, the captain charted a course for the Singapore docks. Not necessarily a bad decision given what the captain knew, but as the ship headed toward Singapore, more water gushed into the front holds than the pumps could accommodate. As the situation got worse, the front of the ship started digging into the waves, making the problem much worse. Finally, about 70 miles from Singapore, the weight of all that water at the front of the ship caused the bow to sink. Like a seesaw, the bow sank below the waves while the stern rose skyward. If the water had been deeper, the whole ship would have sunk, but in the relatively shallow of the archipelago, the bow sank into the mud and left the stern high in the air. After sending distress messages, the crew lowered themselves into lifeboats and abandoned ship.

At first light, several competing Singapore-based salvage companies dispatched experts to assess the stricken ship and offer salvage support. Smit Salvage signed a Lloyd’s Open Form contract, a “no cure-no pay,” agreement to provide salvage services. Evaluation of what the Italian ship owners would ultimately owe would be sorted out later in a London arbitration hearing. The payment due would be based upon a not-so-precise formula weighing the value of the ship, its cargo, and the risk taken to salvage the ship.

As Smit salvors worked to secure the ship’s hatches, the owners signed a second Lloyd’s Open Form with another salvage contractor, Selco. At first everyone agreed to a provisional salvage plan: unload the cargo with floating clamshell cranes and raise the hull by pumping air into the flooded compartments.

With good weather, relatively calm seas, and a stable hull, the two salvage companies worked together to begin dewatering the ship. But then the winds kicked up and heavy sea swells made it difficult for divers to secure air hoses. When the starboard wing tank cracked and flooded, and several hatches imploded under sea pressure, engineers worried the ship might break in half, causing the stern to sink and making salvage impractical. Smit threw up their hands and surrendered the job to Selco. Selco, determined to honor their contract, called Dad. Could he, they wondered, propose a viable salvage solution for the imperiled ship?

The call from Selco came on a Friday. Dad hopped on a flight out of San Francisco International Airport on Saturday morning. I was four, and don’t remember this particular departure, but I remember others like it – calls to travel agents to find the best flight options, the mad rush to pack, the drive to the airport, the waves goodbye, followed by alone time with Mom. I can only imagine what it must have been like for Mom to single parent a toddler with her spouse halfway around the globe, not knowing when he might call or return home.

In Singapore, Dad reviewed photographs of the Igara and discussed diver inspections of the imperiled ship. In between rain squalls, he visited the stranding site to examine the conditions.

My now octogenarian father distinctly recalls the moment he arrived:

When I got there initially, I caught a helicopter from Singapore to the Igara, landed on board and started looking around, and I was stunned by the whole thing. I just couldn’t figure out what to do.

They called me and I showed up, and I vividly remember, they were asking me, “What is the American method of doing this?” And I kept thinking to myself, ‘beats me.’ You know, I didn’t know. There is no American method.

After his initial examination and a little time to ponder, my father concluded there were a variety of possible salvage plans including unloading the cargo, using compressed air to blow out flooded tanks, and utilizing ballasted-down barges to buoy the sunken part of the ship to the surface. The trouble with all of his ideas was that they required substantial equipment, personnel, and time, none of which were present in the South China Sea. Most pressing was time. The ship’s hull was already under stress and monsoon season was coming. A sufficiently strong monsoon would sink the ship and end the project.

Dad had an idea. Kind of a crazy idea, a bit of a high risk one, but one he thought could work.

But he had a few concerns.

I thought the only viable solution was to cut the ship, but if you cut it, would the stern section capsize? Or would it be stable? And I spent a lot of time working on that part of the problem.

And it had to be cut instantaneously, because you couldn’t piecemeal it. You couldn’t take a torch and start cutting somewhere. So it had to be done just in an instant. And the only way to do that would be with explosives. And I had a lot of experience with explosives.

Dad knew that, done correctly, the bow section would sink, and the stern would float free. They even gave the project a code name: STIMS – Slice Tanker in Milliseconds. The explosion might take a fraction of a second, but the preparation and planning to maximize the chances of success would take time. One hundred and eight days, as it turned out, all the while waiting for a storm that might make it all moot.

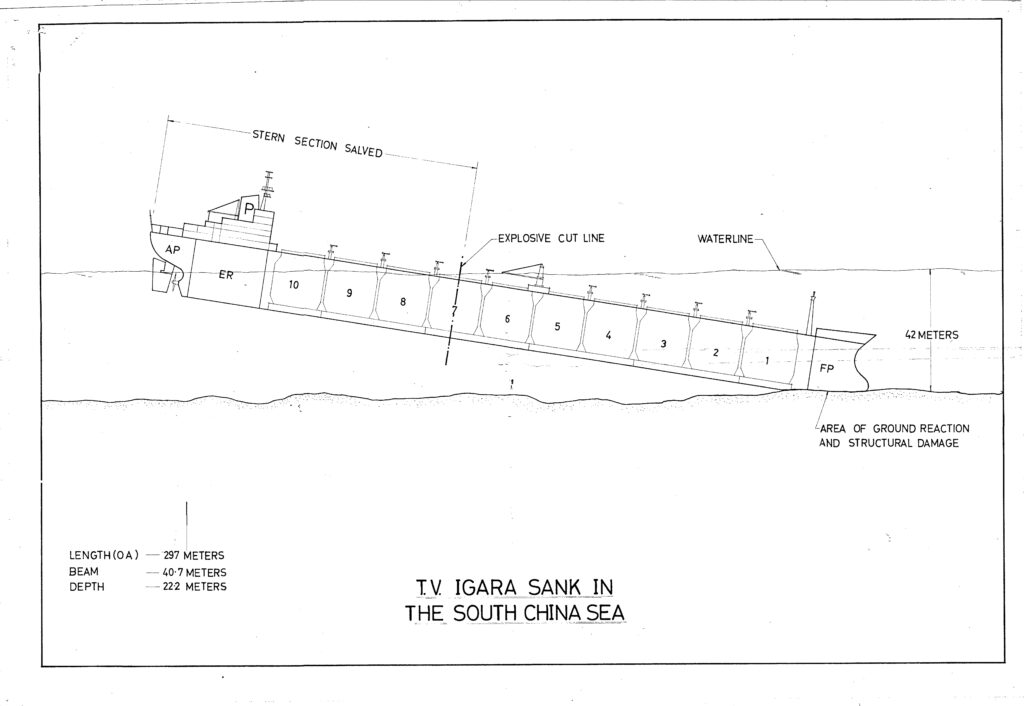

One challenge was where to cut the ship. The 960-foot-long Igara had ten cargo holds. The front six holds were completely flooded, which would make cuts in those holds more difficult. Hold number 7 was not fully flooded, but was still below the water line. So while the ship could theoretically be severed anywhere in front of the valuable stern section, hold seven had two distinct advantages: first that it would require somewhat less work to pump out water, second, and much more importantly, it was at the point of maximum shear, which meant that if some of the explosives failed, the cut itself would still create so much stress on the hull that gravity would finish tearing the ship in half. The decision to cut the ship at hold seven proved relatively easy. Prepping it turned out to be far more complicated.

The team needed the work area for the explosive cut line dry, which meant getting rid of the water in the hold. It is, of course, difficult to get rid of water while you’re in it, and it’s leaking onto your ship through gashes in the hull. The solution: a cofferdam, a watertight enclosure inserted into the undamaged portion of the hold, then pumped dry, making a workable space inside the ship where it was to be cut.

Soon, the team began the painstaking process of constructing the custom-built, vertical, gas-tight cofferdam cylinder. Every detail had to be precise. First, they fitted the ship’s holds with vent lines, carefully testing to ensure no flammable gases lingered beneath the surface. Then, with the precision of a well-rehearsed routine, the divers positioned the massive cofferdam into place, securing it with bolts before pressing concrete against its lip to create a flawless, airtight seal. Only then could they move forward with the internal staging.

The pace of the job was relentless. Days bled into nights with no breaks and little room for anything but the task at hand. If Dad called home during those weeks, his diary never mentioned it. On the 32nd day, he wrote, “This appears to be a very difficult job, and very time-consuming.” But the difficulty wasn’t emotional — it was the sheer grind of it all. The contractors were slow, the work stretched on and on. Yet, despite the mounting frustrations, there was a rare moment of satisfaction when a tubular steel catwalk was finally installed that provided secure, dry access to the cofferdam and the critical cut line, a tangible symbol of progress in a project that had so far inched forward with exasperating slowness.

In late April, bad weather forced the support barges and tugs to anchor off the starboard quarter of the Igara. While divers cut pipes and bulkheads to create a completely open loop for the cut line, pumps expelled water from the ship’s double bottoms.

In May a five-man special explosives team from Xplo Corporation arrived with chemical supplies and began blending Astrolite (a two-part liquid explosive mixture, composed of ammonium nitrate oxidizer and hydrazine rocket fuel) and fitting plastic caps with Primacord (a brand of detonating cord). The team tailored explosives to exacting measurements for placement in a continuous ring around Igara.

Starting on the ship’s deck, the team strung one cutter for each section of steel, ultimately placing nearly 1800 feet of linear and curve shaped charge cutters through the wing tanks, double bottoms, galleries, hatch combings, and back again to the deck.

To successfully cut the ship in half, the high velocity explosives needed to work exactly as planned, and fire as close to simultaneously as possible. While the odds suggested that any one individual shaped charge would fire and the entire explosive line would detonate, there were two things which worried Dad: the gas expansion generated during the detonation of the charges, and the resulting shock wave.

For two weeks, the Xplo Corporation field team, my father, and the Selco salvage crew calculated the pressures from gas expansion, the forces and impulse of the expected shock wave, and potential impacts to the undamaged portions of the ship. These complex mathematical calculations, each iteration done by hand, took time. The resulting data led Xplo to recommend sandbagging the shape charges, creating a blast curtain to minimize potential damage to the watertight bulkheads. Dad feared they might disrupt the electrical circuits and cause failure on the explosive line.

While my Dad played out an assortment of scenarios, the salvage crew fortified portions of the ship with both timber and reinforced steel I-beams. After more proposed changes (mostly all rejected) and several long meetings, Dad plotted his departure and packed his bags. He’d been at work on the Igara for over sixty days.

My Dad left the Igara worksite in late May. Early June brought strong wind gusts, heavy rain, and five-foot swells, threatening the ship and further straining the work crews. Despite the pitching sea, the salvage crew finished placing the charges and installing over 600 sandbags. By late June, Selco was primed and ready, with a literal boatload of guests on board, all eager to witness the moment of truth—the cutting.

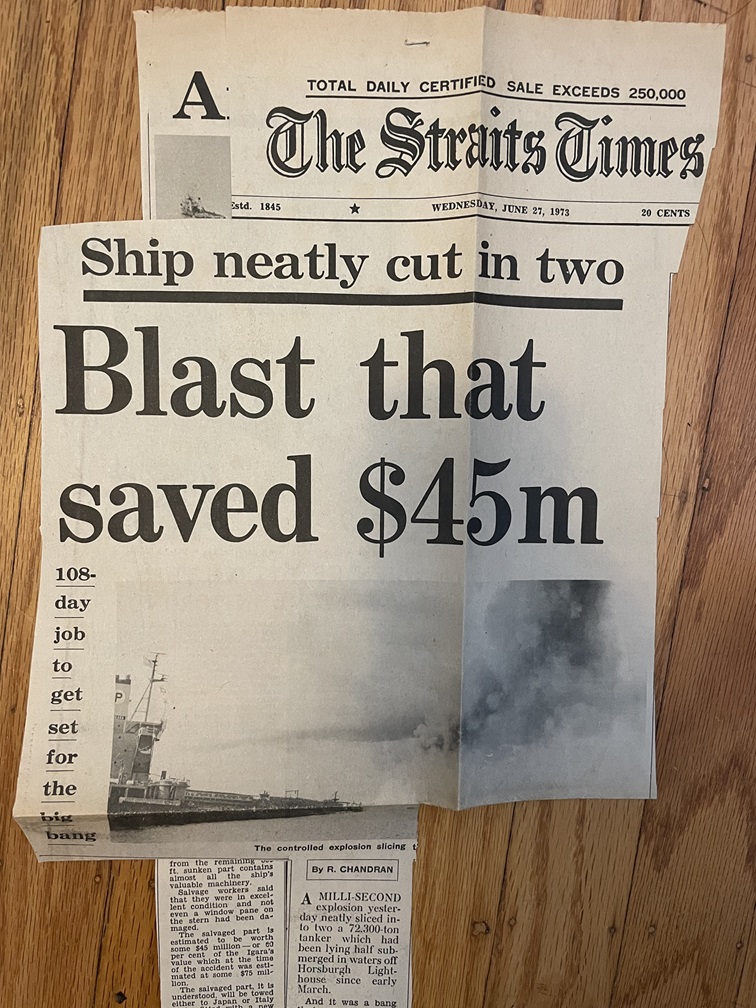

The blast countdown began at 5:30 a.m., and the tension in the air was palpable. With nine salvage ships and barges spread out across the site, coordinating the positions was no small feat. Orders rang out to turn off all radios, transmitters, receivers, and radar — every communication device except for the walkie-talkies. As the main generator aboard the Igara shut down, the explosives crew capped the firing lines, securing the final connections. At 8:43 a.m., the eight seismographic electric detonators fired in perfect unison. A fountain of sea water burst into the air. More than a few guests gasped as the stern appeared to sink, but then, as if a miracle, popped back up up out of the sea. Meanwhile, the bow quietly settled onto the ocean floor.

As the water settled, a small group boarded the Igara to inspect the results. Despite the violence of the explosion, the ship was sound—watertight, intact. Even the most delicate instruments in the engine room, including the sensitive navigational aids, had remained unaffected. Not even a single light bulb had shaken loose. The salvage effort was an enormous success.

It should be noted that at the time of her sinking, the Igara was the largest ever single marine insurance loss in maritime history.

EndNotes:

I hope there are no errors in the descriptions of the Igara salvage job, but if there are things I haven’t gotten quite right, my apologies.

The bow of the Igara is now a popular recreational diving spot.

After the Igara was cut in half and the stern was towed to Japan, a shipyard attached a new forward section. The new ship was called the Eraclide.

Sources

Interview with Alex Rynecki. 6 March 2024.

Blast that Saved $45m. The Straits Times. 27 June 1973. found https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19730627-1.2.2

Loss of Igara Jacks Up the Bill. The Straits Times. 8 January 1974. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19740108-1.2.120

The Business Review. Volume 1. No: 12. Mar/Apr M.C.(P) No: 172/74

- “Explosives Save Ship from Total Write-Off”t

- “The Igara: a “Titanic” Salvage Undertaking”

“Explosive Surgery Saves Bottomed Ore/Oil Carrier: Valuable Stern Section Saved in Classic Open Water Salvage”. Fairplay International Shipping Weekly. 15 August, 1974.

“Talking About – Large Losses and Insurance. Fairplay International Shipping Weekly”. 28 February 1974. Pages 59-63.

“Salvor’s Blast Saved Ship’s Machinery”. Ship Intelligence. [file clipping. unclear of the date it was published.]

“Salvage Effort for ‘Igara’” World Dredging & Marine Construction. September 1974. Pages 47-48

“Hydrography for Surveyor/Engineer.” [file clipping. Unsure of the publication name or date.]

“Worst-Ever Major Ship Casualties”. [file clipping. Unsure of publication.] 19 April 1973.

Igara – Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Igara_wreck