Thank you to Dr Roger Knight for this fantastic article about how the Royal Navy’s administrative and financial structure was altered at the end of, and following the Napoleonic Wars. Roger’s interests for most of his museum and teaching career have been in the field of naval history. He read history at Trinity College Dublin and completed his Ph.D at University College, London in 1972, on the Royal Dockyards in England at the time of the American Revolutionary War. For twenty-seven years he worked in the National Maritime Museum, starting in the manuscripts department in 1974 and leaving as Deputy Director in 2000. From that time until 2014 he was Visiting Professor of Naval History at the Greenwich Maritime Institute, University of Greenwich. He is now a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Historical Research, University of London.

Thank you to Dr Roger Knight for this fantastic article about how the Royal Navy’s administrative and financial structure was altered at the end of, and following the Napoleonic Wars. Roger’s interests for most of his museum and teaching career have been in the field of naval history. He read history at Trinity College Dublin and completed his Ph.D at University College, London in 1972, on the Royal Dockyards in England at the time of the American Revolutionary War. For twenty-seven years he worked in the National Maritime Museum, starting in the manuscripts department in 1974 and leaving as Deputy Director in 2000. From that time until 2014 he was Visiting Professor of Naval History at the Greenwich Maritime Institute, University of Greenwich. He is now a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Historical Research, University of London.

In 2005 he published with Allen Lane, Penguin, The Pursuit of Victory: the life and achievement of Horatio Nelson. As part of a Leverhulme grant project on the victualling industry at the time of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, he published with Martin Wilcox, Sustaining the Fleet: War, the Navy and the Contractor State, 1793-1815 (Boydell, 2010). His most recent book was Britain against Napoleon: the Organization of Victory, 1793-1815, again published by Allen Lane, in 2013. He is currently working on a book for Yale University Press on British convoys in the Napoleonic War, to be published in 2022. For more details see http://rogerknight.org.

This article was originally a paper given at the National Maritime Museum/Institute of Historical Research seminar at the IHR, 25 March 2014

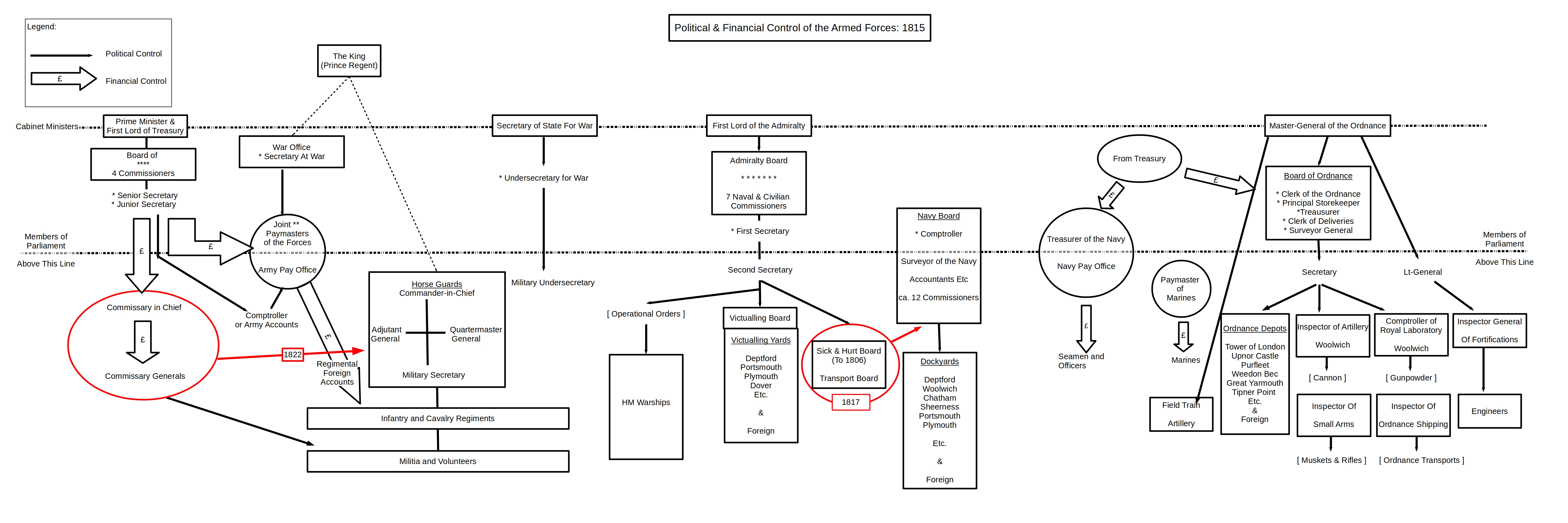

In 1832 the Navy Board was abolished by Lord Grey’s Whig government, after five years of instability in the administration of the navy, brought about by bizarre political circumstances. This began with the appointment in 1827 of William, Duke of Clarence (later William IV) as Lord High Admiral. For William’s term of office of fifteen chaotic months, the First Lord of the Admiralty and the Admiralty Board was replaced by the Lord High Admiral, advised by a Council of four. Five years later the end came for the Navy Board, but it was not the only loser. Further radical reform of the financial resulted in the Board of Admiralty ceasing to become a great, independent Department of State. By 1835 Treasury financial and political control of all the armed forces was complete.

The Navy Board, responsible for ship design and building and the dockyards, was deeply unpopular with the serving navy in the 1820s. In 1831, An anonymous pamphleteer who signed himself ‘Commander’ published a short pamphlet entitled The State of the Navy of Great Britain.

I know not why or wherefore, but certain it is, that the Navy Board is the most unpopular department of our whole naval establishment and, in their professional views, are completely at variance with all practical seamen. They have the character of invariably opposing every kind of plan or improvement suggested to them, unless emanating from one of their own body…The Navy Board should bear in mind that one set of men have to build ships, and another have to fight them. There can be no question which of the two are most interested in their state of efficiency; the honour, credit, and even the lives, of one party are at stake, whilst the other risks nothing…and so it will continue until the whole Board is re-modelled and constituted (as I hope at no distant day to see it)…’

1

and he wanted the Board to be made responsible to admirals and captains. This was to come about in 1832.

This complaint was not new. Similar friction between captains and dockyard officers can be traced back through the eighteenth century and beyond. There had always been local difficulties between the civil and military officers in commissioning warships, accentuated by the social distance between the sea officer gentlemen and the lesser technical workers, by national and local politics and a host of other tensions. The natural tendency of the sea officer to blame the dockyards and shipbuilders for failure and shortcomings is a long tradition which has not completely died today.

Comment on this period is still dominated by the 1897 account of the naval bureaucrat, Sir John Briggs, who was a junior clerk in the Admiralty during the Napoleonic War and rose to Chief Clerk at the end of the nineteenth century. His account of that period was published in Naval Administrations after his death. Briggs chastised Lord Melville, First Lord from the end of the Napoleonic War and for most of the 1820s, whose ‘retrograde proclivities’, as he called them, were only too well known, and therefore ‘nothing in the shape of reforms or improvement could reasonably be expected during his tenure of office’.2 Melville was seen as a cold personality and was very unpopular, and indeed, when it came to appointments, carried the principles of the old Scottish ‘Dundas despotism’ into the navy. Our anonymous ‘Commander’ contrasted the difficulties that sea officers had with Melville with the welcome he had received from the Duke of Clarence. ‘To become a popular First Lord’, he remarked, ‘is not a difficult task, but it requires some little tact’ 3 Briggs characterised Melville’s administration as ‘the era of donkey frigates, over-masted sloops, and coffin gun-brigs’.4 He took his prejudices further by describing Sir George Cockburn, the Duke of Clarence’s fiercest antagonist on his Council, as ‘the most uncompromising representative of things as they were. He seemed to live in the past and was impressed by the conviction that everything that had been done was right; that what was being done was questionable, and every step in advance was fraught with danger’.5

This controversial period in the 1820s has been variously treated by recent historians. Andrew Lambert whose writing stresses the technological development of the navy, is a staunch admirer of Lord Melville and of his Comptroller, Sir Thomas Byam Martin, for laying down a sufficient fleet.6 His brief criticism of Clarence ‘unorthodox, if well-meaning enthusiasm for gunnery and an experimental cruise that led to a breakdown of relations with his Council’.7 Roger Morriss has traced the arguments of these years in his detailed 1997 biography of the talented and outspoken Sir George Cockburn, and in particular the steady breakdown in relations between the Duke and his Council, of which Cockburn was a ferociously effective member. Cockburn rather than Clarence, naturally enough, is the centre of this book, though the paths of the two officers were parallel and conflicting for the best part of a year and much can be gained from this account. In the recriminations that brought about Clarence’s resignation, he said that he would only remain if Cockburn was sacked from the Council.8 A rigorously administrative and political approach was taken by Ian Hamilton in his long 2011 study, The Making of the Modern Admiralty, 1805-1927 and in his articles on John Wilson Croker, the Admiralty secretary. The purpose of this paper is to look beyond the Admiralty, across the administration of the British government to see what was happening in Parliament and other departments of state, and to analyse how these political forces impacted on the abolition of the Navy Board.9

The Navy had always been administered by two separate authorities, both with medieval origins. The Admiralty Board was responsible for policy, politics and senior appointments. The Lord High Admirals had been appointed from the mid-fifteenth century, but from 1628 this powerful position had been held ‘in commission’ ie by several commissioners rather than one, and though it reverted for periods to being held by one person, the Lord High Admiral. The last such appointment in the eighteenth century had been the Earl of Pembroke in 1708-9, and just before him Prince George of Denmark, between 1702 and 1707. But during the eighteenth century the administration stabilised as the Board of Admiralty, overseen by the First Lord, a member of the cabinet, and five commissioners, usually all MPs. There were a relatively small number of supporting clerks, housed in Whitehall in the Ripley building of 1723.

The Navy Board and its much more numerous support staff were housed in Somerset House, in the Strand. The responsibility here was for the naval establishments and finance, especially the dockyards, materiel, shipbuilding and design, and could trace its origins even further back to the mid-fourteenth century with appointment of the Clerk of the Kings Ships. By the fifteenth century this official headed, in Susan Rose’s words, ‘busy, well-organised and relatively well-financed ‘departments of state’.10 The successor of these officials was the Navy Board, headed by a sea officer, the Comptroller of the Navy, consisting mainly of civilian technical staff, of whom the most senior were appointed by the First Lord of the Admiralty. The most important was the Surveyor of the Navy, responsible for warship design and building, but other civilian administrators and accountants had significant functions. From the seventeenth century the Navy Office was staffed by an increasing number of clerks, matching the increased size of the navy. Their imposing offices in Somerset House were situated next to the Navy Pay Office and the Victualling Office.11

One of the themes of this paper is to trace the relationship between successive heads of the two main boards, the First Lord of the Admiralty and the Comptroller of the Navy, upon which the efficient running of the navy was overly dependent. Party, politics and patronage could and did make for difficulties in achieving a comfortable working relationship. The first noticeable tension between the heads of the two boards arose during the American Revolutionary War when the ambitious and forceful Comptroller, Captain Charles Middleton, challenged the First Lord, the urbane, competent but politically weak Lord Sandwich, over the right to appoint dockyard officers, claiming (logically) that the Admiralty had no way of knowing which dockyard officers were competent and only the Navy Board could do this adequately. Sandwich dealt with Middleton tactfully, for the First Lord was not going to give away patronage rights and thus political power, so the situation was unchanged.12

After the fall of the administration of Lord North in 1782, and the departure of Sandwich, the ensuing peace in the 1780s brought Lord Howe to the Admiralty, along with his quarterdeck skills, but not much else. Another long-term cause of friction within the navy was that between the different traditions and behaviour of those whose natural ground was the quarterdeck, conflicting with the more subtle political world of the bureaucrat. After a couple of years, Howe and Middleton were hardly on speaking terms and Howe took pleasure in either goading or ignoring Middleton, who spent the decade of the 1780s trying to make the dockyards more efficient. Howe’s surprise inspection of the dockyards, for instance, when he found much to criticise, was undertaken without the First Lord informing the Comptroller that he was intending to inspect them, in spite of the fact that the dockyards were very much Middleton’s territory. But Middleton eventually won the political battle. Howe resigned in 1788 on the question of Middleton receiving his flag. As Middleton had had an undistinguished career at sea, Howe opposed his promotion to rear-admiral, but William Pitt, the Prime Minister, backed Middleton and the First Lord’s isolation from the rest of the Cabinet contributed to Howe resigning in disgust.

Ten years of relative peace between the two offices followed. William Pitt’s brother, Lord Chatham, succeeded Howe, and was idle and aloof. Nevertheless, Middleton, frustrated by William Pitt’s reluctance to implement reforms in the Navy Office and dockyards, suddenly resigned, to the relief of his Navy Board colleagues.

Middleton was succeeded by Captain Henry Martin, who had little ambition and died just as William Pitt relieved his brother of his duties in 1794. Lord Spencer, aristocratic whig and bibliophile came in as First Lord with the Portland Whigs in coalition with the Tories. His character was famed for affability rather than effectiveness. He came to the office at the same time as the Comptroller, Captain Sir Andrew Snape Hamond, and there were few altercations for the rest of the 1790s.

This calm came before the hurricane, for between 1801 and 1805 the Navy was continually at the centre of a bitter political storm. The First Lord of the Admiralty in Addington’s government formed in 1801, Lord St Vincent, as a committed Whig and the toughest and most intransigent naval officer of his generation, was determined to root out what he saw as wholesale corruption in the dockyards and victualling yards. This conviction was matched by his distrust of contractors: and he went all out to cut government expenditure. There were unquestionably reforms to be carried out, but St. Vincent brought quarterdeck methods to a part of the administration which operated, as bureaucracies do, by negotiation – and not by directives and confrontation. The First Lord carried on a vitriolic struggle with the Navy Board, and he and Hamond carried the battle into Parliament. If St Vincent could have abolished the Navy Board, he would have done so. In June 1802 Hamond declared in the House of Commons with impatience that ‘it was impossible to go on as things now stood’. Under pressure, he later modified this to more appropriate Parliamentary language, and with a large dose of irony, ‘that the Navy Board was not thought so well of by the present Admiralty as by their predecessors’.13 As it was, in 1803 St Vincent set up the Commission of Naval Enquiry ‘to enquire and examine into any Irregularities, Frauds or Abuses, which are or have been practised by Persons employed in the several Naval Departments’. After the Peace of Amiens was signed in March 1802, St Vincent sacked dockyard employees and cancelled timber and shipbuilding contracts, leaving the dockyards short of supplies, a particularly dangerous embarrassment when war was resumed in May 1803.

The struggle did not end with the demise of Addington’s administration. When St. Vincent left office in 1804, Henry Dundas, Lord Melville took over as First Lord, did well briefly, reversing some of St Vincent’s policies, encouraging the dockyards and contractors, by which means the fleets got to sea, and ensured that Nelson had enough ships to fight the battle of Trafalgar. But Melville was then obliged to resign after the scandal over the Treasurer of the Navy’s accounts some years before, which was exposed by the tenth report of St. Vincent’s Commission of Naval Enquiry. Charles Middleton took over, at a very advanced age, elevated to the peerage as Lord Barham for his trouble: As he was so old it looked a makeshift appointment – as indeed it was. Barham’s period at the Admiralty was short as the Tory government fell in 1806 after the death of William Pitt. Hamond then quietly resigned as Comptroller of the Navy Board.

There then followed an interesting and not much remarked upon ten years from 1806 until the end of the war in 1815, when the Navy Board was led by Captain Sir Thomas Boulden Thompson, made a rear-admiral in 1809. This Comptroller served with five First Lords – Charles Grey, Tom Grenville, Lord Mulgrave, Charles Philip Yorke and the second Viscount Melville and through periods of great difficulty and change, which saw the expansion of the navy. Thompson implemented the reforms of the Commission of Naval Revision, which involved wide-ranging changes in the bureaucracy: new technology was introduced into the dockyards, yet there were no strikes and their work rate went up radically: by 1815 at Portsmouth, for example, the throughput of docking warships, measured in ‘ton-dock days’, more than doubled between 1793 and 1815. Thompson brought the Navy Board and Office, and the organisations which it governed, to a peak of efficiency in the last years of the war.

Exactly how he managed to achieve so much needs explanation, but it has not been explored, though undoubtedly money was more plentiful, at least in the last three years of war. Thompson had an unassailable seagoing reputation in the fighting navy as one of Nelson’s captains, with distinguished service at Santa Cruz and the Nile. Commanding the Leander, he took home Nelson’s despatches, but was caught by Le Genereux one or the two French 74s which escaped the Battle of the Nile, and was overwhelmed in a very bloody engagement. Thompson was wounded and taken prisoner, eventually returning to England in an exchange of prisoners. Exonerated with honour by the court martial on the loss of his ship, Marshall describes the scene: ‘Upon the return of Captain Thompson to the shore from the Alexander, in which the court martial had been held, he was saluted with three cheers by all the ships in the harbour at Sheerness’.14 this is the only sign I have found of a particularly high service-wide reputation. Thompson then fought at Copenhagen, when he lost a leg, and as a result came ashore, with a pension and a baronetcy. This quiet, respected officer has been largely overlooked by historians, and he kept a low profile – efficient administrators are often ignored – hardly spoke in Parliament, yet made one of the most valuable contributions to the British war machine during all the Napoleonic war.

After the end of the Napoleonic war, Thompson retired in 1816 and was succeeded by Thomas Byam Martin, who served for fifteen years until his dismissal in 1831. He was a different character from his father, Henry Martin, Comptroller in the 1790s. Byam Martin had been a successful frigate captain – acerbic and forceful, and whatever the volume of political criticism, was no shrinking violet. He got on with his First Lord, Lord Melville so well ‘in the most confidential situation nearly fifteen years’, that he is said to have agreed the Naval Estimates privately in the First Lord’s office.15

However, the expense of the Napoleonic war had swollen the National Debt to unprecedented levels and a peacetime House of Commons was intent on slashing state expenditure: The Admiralty made immediate economies, laying up the fleet so that only a sixth of the tonnage was in commission, if measured from its highest point, in 1813. Some economies were made as a result of Parliamentary Select Committees in 1817 and 1822. The Transport Office was abolished in 1817, and as it had taken over the Sick and Hurt Office in 1806, all these functions were taken over by the Navy Office. A review in 1821 reduced clerical staff by 50 clerks in the Admiralty, Navy and Victualling Offices. Cuts in the dockyards were also made. The Admiralty commissioners were reduced by two from seven to five. The Treasury tried to reduce salaries, but the Admiralty fought back.

All these traditional, imperfect checks and balances were, however swept away in February 1827. Lord Liverpool, the Prime Minister, who had been in office for fifteen years, suffered a stroke. After the usual manoeuvring, George IV asked George Canning to form a government. Although Canning had been a brilliant foreign secretary in 1807 to 1809, and again in 1822 to 1827, he was highly distrusted by the right wing of the Tory party, which was anyway split on the issue of Catholic Emancipation. The First Lord of the Admiralty, the 2nd Lord Melville, declined, as did many others, to serve under Canning, in spite of the fact that he, like Canning, was pro-Catholic. Melville resigned, Canning’s biographer concluded, ‘for no reason than that so many of his colleagues had done so, and his condescending assurance that he did not wish to ‘unnecessarily accelerate’ his retirement only added to Canning’s disgust. ‘This is the basest of all’, Canning wrote, ‘for here is no reason pretended except that of prudent speculation. I’ll accelerate him’.16

In some desperation at finding a suitable First Lord, Canning turned to the sixty-two year old Duke of Clarence, the future William IV.17 He was made Lord High Admiral on 2 May 1827. It was a time of high political drama. Charles Greville observed in his Memoirs that:

‘it is not possible to imagine greater violence and more intense curiosity and anxiety than have been exhibited. The violence and confusion of parties have been extreme – the new Ministers furious with their old colleagues, the ex-Ministers equally indignant with those they left. [Canning’s] first measure was very judicious – that of appointing the D[uke] of Clarence Lord High Admiral – nothing served so much to disconcert his opponents’.18

In taking this unorthodox decision for short-term political gain, one said to have been suggested by John Wilson Croker, the First Secretary of the Admiralty, Canning was harking back a hundred and twenty years. The patent that appointed Clarence was essentially the same as the 1702 patent which appointed Prince George.19 But Clarence had just become the heir to the throne, since Clarence’s older brother, Frederick Duke of York, had unexpectedly died in January 1827, and this overlooked fact meant the exclusion of the Lord High Admiral from the deliberations of the Cabinet.20 All this was due to the long tradition of keeping the monarchy apart from the levers of power: the government was following the precedent of the French wars when the Duke of York as Commander in Chief of the Army was excluded from higher deliberations of strategy. When Lord Chatham was Master General of the Ordnance, with a seat in the Cabinet, when he was excluded from its deliberations when appointed to command the Walcheren expedition in 1809.

Clarence was to be advised by a council. On 12 April 1827 Canning wrote to Lord Melville – not surprisingly in a sardonic tone – that ‘His Royal Highness appears very good naturedly disposed to retain the whole of your Board, or at least as many of them as are disposed to stay’.21 There were four on this Council, of which the most dominant, if not the most senior was Vice-Admiral Sir George Cockburn. In order to compensate partly for the absence of the head of the navy at Cabinet, Cockburn was made a member of the Privy Council which gave the junior member of the Lord High Admiral’s council increased influence and access to powerful figures.22 Unsurprisingly, this disastrous administrative arrangement soon led to major ructions between the Lord High Admiral and a junior but well-informed and politically powerful member of his Council.23

After only a hundred days as Prime Minister, Canning died, and, after Lord Goderich’s short unsuccessful administration, the government which followed was led by the Duke of Wellington. He tried to manage his senior royal sea officer, the Duke of Clarence, who, though he had a council to advise him, could argue that all power was in his hands, whereas it had in effect all but disappeared, quite apart from his ignorance of the Cabinet’s intentions.24 Clarence’s letters to senior admirals were completely uninformed on political or strategic considerations, and contain nothing but issues on the appointment and promotion of junior officers on station, and one or two platitudes about how an admiral ought to behave. To Edward Codrington out in the Mediterranean, Clarence explained his frustration: ‘The fighting after all is the first duty of a British Man of War… As the state of the country will not permit like the Duke of York of my commanding in case of war the Fleet before the enemy, I am determined to do my best to send our Navy as fit as possible to conquer the world’.25 Three months later he wrote: ‘I recommend to you firmness and coolness’, when Codrington had displayed plenty of the first, but none of the second, in his dealings with the Turks at the battle of Navarino in 1827.26 It is no wonder that he congratulated Codrington having just heard of the news of the battle, ‘on your splendid victory you have obtained and rejoice that you are quite well. I admire you for your conduct on the day of the battle…’.27 The Cabinet, on the other hand, wishing to prop up Turkey to neutralise Russia in the Eastern Mediterranean, was highly displeased that any shots had been fired.28

Only perhaps to Sir Charles Ogle on the North American station are Clarence’s letters better informed, for he had served there as a captain: but his advice and sentiments were hardly profound. ‘I do not believe the Americans will ever turn against us singlehanded. Still, however, we ought to be prepared for the worst’.29 Disconcertingly, in his letters to Sir Robert Stopford, Commander-in-Chief at Portsmouth, he addressed his official letters to that admiral ‘Dear Bob’, reflecting that he had known Stopford for 48 years.30

Yet Clarence was popular with naval officers. Over a decade of cutbacks and with few ships commissioned, the fighting navy felt neglected. One way in which the Lord High Admiral endeared himself to the serving navy was his frequent visits to Portsmouth to inspect the fleet and dockyard, though doubts were raised about the expense of these exercises, which, as Clarence’s private secretary noted to Stopford, was ‘a very delicate point to touch although no doubt the expenses are exceeded by such visits’.31 But some seamanlike reforms were made. A committee of senior officers, led by Rear-Admiral Sir Thomas Masterman Hardy, was charged by Clarence to review gunnery systems, complements and drills, and at the end of Clarence’s term it reported in August 1828 with some sensible practical improvements.32 The Lord High Admiral required quarterly reports on gunnery exercises and the expenditure of ammunition and he made reasonable decisions on promotions.33

In July 1828 Clarence took things further. Without telling his Council, he embarked on the Royal Sovereign yacht in the Thames, ordered the members to meet him at Portsmouth and to stay there at his pleasure. Cockburn immediately took issue with this order, arguing that it was against the Act setting up the Lord High Admiral’s administration, and that for the Duke to hoist his flag at sea was contrary to constitutional form. Clarence sailed to Plymouth, exercising the guardships – which never usually left their moorings in peacetime – in manoeuvres and gunnery, though nobody in London quite knew where he was: the row within his Council dragged on and eventually Wellington persuaded George IV that he should force Clarence to resign.34 He was succeeded by Lord Melville who returned to his post as First Lord.

Clarence had been disastrous. He had issued orders on his own account, not in conformity with his patent, which had been drawn up to specify that all orders from the Lord High Admiral should be acted upon by members of his council. Towards the end of his period of Lord High Admiral, Melville wrote to him emphasising the importance of acting with and through his Council:

I am persuaded that with the official experience which Your Royal Highness must have acquired it is unnecessary for me to remind you that nine-tenths, or probably a much larger proportion, of the business of the Admiralty office is more of a civil than of a strictly naval character, and that the official course of proceeding in regard to it ought to be in conformity to what prevails at the War Office, or the Ordnance Office, or any department where the business is of a similar description with what is transacted at the Admiralty…No man’s physical health and strength are equal to it and any attempt at a different course of proceeding must be most injurious to the public service.35

Clarence was the last sea officer to lead the navy. Subsequent First Lords of the Admiralty were politicians, although the First Naval Lord, the most senior service officer serving on the Board of Admiralty under the First Lord, could be very powerful. By the end of the nineteenth century these officers were known as the First Sea Lord, of whom Sir John Fisher and his combustible relationship with the First Lord, Winston Churchill, at the beginning of the First World War is probably the most well-known example.

****

It was in the middle of the political vacuum generated by Clarence’s time as Lord High Admiral that the process began which was to end in the abolition of the Navy Board. On 15 February 1828 Robert Peel put forward a motion for a further Select Committee to, as the House of Commons Journal has it,

To inquire into the State of the Public Income and Expenditure of the United Kingdom, and consider and report to the House, what further regulations and checks it may be proper, in their opinion, to adopt, for establishing an effective control upon all charges incurred in the receipt, custody and application of the Public Money; and what further measures can be adopted for reducing any part of the Public Expenditure without detriment to the Public Service.36

It was a strong, all-party committee of twenty-three, and included the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Henry Goulburn, and government financial experts John Charles Herries and William Huskisson, opposition whigs Lords Althorp and Howick and the radical MPs George Tierney and Joseph Hume. But a chairman emerged who is unknown today. He was an Irish whig of some eccentricity and was to be particularly effective in pressing for economy: he was described by a fellow member as:

a respectable but by no means a superior speaker. He has a fine clear voice, but he never varies the key in which he commences…What he excels in is giving a plain, luminous statement of complex financial matters. In this respect he has no superior; I doubt if he has an equal in the House.

This was Sir Henry Parnell, who hitherto had had little prominence bar regular financial criticism of the levels of government expenditure. The Select Committee was short lived (and its papers have not survived, possibly destroyed when the Houses of Parliament were burnt down in 1834) but it asked hard questions. The two main upholders of the status quo defended the levels of naval manning afloat and ashore. Sir George Cockburn was, for instance, asked why more seamen were needed in 1828 than in 1792, the last year of peace before the French Revolutionary War, and although he gave, as usual, a persuasive answer, the feeling now spread within Parliament that the navy was costing far too much. Sir Thomas Byam Martin overplayed his hand when questioned by the Committee in a performance which was over-jubilant about the naval victory at Navarino, and he gave a passionate, unyielding defence of the current strength of the Navy. The Comptroller’s evidence created a strong impression that the Navy Board was too big and powerful, and not subject to cost constraints.37

The four reports in 1828 which the Select Committee did publish started political momentum towards financial reform of the armed forces, though it was not re-appointed for the 1829 session, much to Henry Parnell’s disgust. In order to be seen to react to the navy’s critics, in January of that year Wellington persuaded Lord Melville to make changes in the organisation of the Navy Board, giving each Commissioner the individual responsibility for specific tasks, such as stores, construction and repairs or transports – rather than having the three Committee system which had been imposed in 1796. As Master General of the Ordnance, Wellington had found that the system had worked well at the Ordnance Board.38

But this was a time of increasing political tension, and discontent and disturbances, and petitions from all over the country for Parliamentary reform. In 1828 Daniel O’Connell’s oratory caused the issue of Catholic Emancipation to come to boiling point and in 1829 the government gave way and compromised. The General election of 1830 was indeterminate, though Wellington’s government resigned in November 1830. Traditional institutions were under attack, and the government was under pressure to reduce governmental costs and the Navy Estimates were especially the target of the reformers. In these years, pages and pages of detailed paragraphs in the House of Commons Journal demonstrate the level of detail to which the Estimates which Parliament were subjected. Just one example:

That a sum, not exceeding nine hundred and two pounds, eleven shillings, be granted to His Majesty, to defray the charge for Provisions for the Officers and Men of the Yard Service Afloat, 1 January to 31 March 1832 39

This was a remarkable flexing of Parliamentary muscle, since there had been no printed Naval Estimates until 1810 available to Parliament at all, and, as a consequence, no informed debate could take place.

Meanwhile, Sir Henry Parnell was busy. What he might have lacked in oratory he made up for in energy and publication. He carried on the work of the Select Committee of 1828 by his book On Financial Reform, published in 1830. It covered many areas of political life which he considered too costly, and particularly the colonies, but the two chapters which cover the economies to be made in the army, navy and ordnance were powerfully argued. (This publication has often been referred to as a pamphlet, but it is very much more than that. I used a copy of the fourth edition of 1832, which means that four editions were published in two years: it was clearly widely read.)

What made his argument in this book so powerful and detailed in its criticisms was that the Select Committee of 1828 had sent in three ‘mercantile accountants’ to examine the books and working practices of the Army, Ordnance and Navy. The two reports from these three private sector accountants (Messrs. Abbott, Beltz and Brookebank) made sweeping criticisms of all three services. For the navy, there were three main concerns: overmanning in the dockyards; manufacturing when the private sector would be cheaper and better: and unnecessary and unfocussed accountancy methods. Much of the evidence for the overmanning in the dockyards came from Sir John Barrow, as second secretary of the Admiralty, from his observations from dockyard visitations. ‘There is not a single trade’, wrote Parnell, ‘carried on in the dockyard(s) which has not a master’, each at a salary of £250 a year. ‘At Sheerness, for instance, the Master Bricklayer superintends five bricklayers’.40 The book was also highly critical of an overabundance of measurers, by which the work of shipwrights and other workers was paid, a system which was imposed by the Commission of Naval Revision in 1809, at the height of the effort against Napoleon. And there was the inevitable comparison with private shipyards. Woolwich dockyard was quoted as an example – 248 shipwrights, 18 clerks, 6 masters of trades, 8 foremen, 8 measurers, 11 cabin keepers, besides the surgeon, boatswain, warders and other supporting staff. A comparable private yard of 250 shipwrights would have two clerks, one foreman, one measurer and ten labourers.

There was harsher criticism of both the navy (and the ordnance), which, according to Parnell,

defend the practice of manufacturing by claiming that what they make is cheaper and better than they could be provided by contract; but such a defence rests upon what is morally impossible; because private manufacturers can buy materials cheaper, and take better care of them; and they can get labour cheaper, make it go further and superintend it better, and at less expense than any public office… 41 …the employment of a great many officers, clerks, artificers and workmen, and not only adds to the patronage but to the appearance of the importance of a department’. Nor can the Finance Committee suffer themselves to feel any prejudice against the contract system by references to some instances of failure. They believe that most cases of failure may be attributed to negligence or ignorance in the management of contracts, than to the system itself.42

The final straw was naval accounting, which had no clear rules or uniformity. No clear distinction between the duties of the Navy Office and of the Treasurer of the Navy, ‘

it appeared to us that they had been modelled more for the purpose of checking the accounts of the Treasurer of the Navy, than for affording any explanatory detail of the Navy expenditure’ 43

and Parnell here quoted the accountant, Mr Abbott, who said,

Every government office has its peculiar system; and that if he were employed professionally to test the accuracy of any of the accounts he would put aside every book in use, and taking up the original documents, throw them into a totally new shape.

Having marshalled the evidence, Parnell’s conclusion was clear: ‘What is still wanted, ‘is to unite the three Boards of Admiralty, Victualling Office and Navy Office, into one Board’.

Sir Byam Martin took the book as a personal attack upon himself. A parliamentary row followed in 1830 and in the debate the old arguments current at the time of St Vincent in 1803-5 were revived, and the view that the Navy Board was inefficient and corrupt reasserted itself. Martin held strong views on what was required to defend Britain in a future war, yet proclaimed that he was not a politician and was not going to resign. He was, however, governed by pronounced Tory views. He wrote later of Britain at this time as,

A people divided against each other…with feelings embittered by the most rancorous party prejudice, the one desiring democracy and confusion, the other struggling to maintain monarchical institutions and good government 44

In late 1830 Lord Grey formed a Whig Government, the first for twenty-three years and the young and energetic Sir James Graham was made First Lord of the Admiralty. Graham brought in the Admiralty Act (2&3 Will IV c.40) when, for the first time, the Navy and Victualling Boards were abolished and the entire civilian administration of the navy was put under the direct control of the Admiralty. As 1832 is the year of the Great Reform Act, passed amid drama and political disorder in different parts of Britain, this measure of financial reform has been largely obscured.

The government did not merge the Army and the Ordnance that was one of the key recommendations of the Select Committee, to be found in Parnell’s book. The Ordnance survived as an independent government department until it the Crimean War when it was put under the Army Board. Instead Grey’s government decided upon the radical reform of the navy, which had been politically vulnerable since the start of Clarence’s term as Lord High Admiral.

In the years that followed the demise of the Navy Board, the government under Lord Melbourne took even more radical steps which were to take away control of the budgets from all three services. On 20 April 1835 Sir Henry Parnell was gazetted Paymaster-General of His Majesty’s Forces and also Treasurer of the Ordnance. In August of that year the Acts 5&6 Will IV cap.35: ‘An Act for consolidating the Offices of Paymaster-General, Paymaster and Treasurer of Chelsea Hospital, Treasurer of the Navy and Treasurer of the Ordnance’ was given royal assent. The recommendation of Parnell’s book had come to fruition.45

Get rid of the offices of Paymaster of the Forces, Treasurer of the Navy, Treasurer of the Ordnance, Paymaster of the Marines, and twenty or thirty other paymasters, with their deputies, cashiers, sub-cashiers and clerks.

(The mediaeval office of Treasurer of the Navy was to be abolished by Treasury Warrant of 1 December 1836.)

Governments in the mid-1830s, with Parnell as Paymaster-General, brought the expense of the armed forces down to the lowest level ever experienced in the nineteenth century. The Army and Ordnance expenditure in 1827 (when Clarence was appointed Lord High Admiral) together totalled £10.2 million, compared to 1836, only £7.6 million – a reduction of 25 per cent. For naval expenditure the reduction in the level of funding for the same date fell from £6.5 million to $4.1 million: a drop of £37 per cent. The navy, which had been swollen by a great war up to 1815, was eventually brought down. The end of the Navy Board was due to neither the fighting navy’s triumph over civilian naval bureaucracy, nor was the Benthamite ideas of ‘individual responsibility’ in any way responsible.46 It was because there was a widespread feeling that the Navy Board and the extensive establishments that it controlled were too independent and too costly. These major changes wereonly one part only of a government-wide victory of the accountants and the Treasury for the control of all armed forces expenditure. When it lost control of its budgets, the Admiralty ceased to become the great office of state of old, a difference which can be measured by the reduction of the quality and profile of the politicians who oversaw the navy for the rest of the nineteenth century.

Henry Parnell was raised to the peerage as Baron Congleton in 1841 and in the following year, rather surprisingly, in view of the success of his measures, he hanged himself. His monument lies in the still-existing post of H. M. Paymaster-General, handled for many years by a minister in the Cabinet Office, though very recently the duties have been transferred to the Financial Secretary to the Treasury.

****

Bibliography

Mss: NMM, Papers of Sir Edward Codrington (COD/)

Papers of Sir Charles Ogle (OGL/)

Papers of Sir Robert Stopford (STO/)

Gunnery Reports (GUN/8)

Anon, ‘Commander’, The State of the Navy of Great Britain (London, 1831)

Aspinall, Arthur, The Formation of Canning’s Ministry, February to August 1827

(London, Royal Historical Society, Camden Third Series, LIX, 1937)

The Letters of King George IV, 1812-1830 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1930)

Bartlett, C.J., Great Britain and Sea Power, 1815-1853 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963)

Bonner-Smith, David, ‘The Abolition of the Navy Board’, Mariner’s Mirror, 31, 1945, pp.154-9

Briggs, Sir J.H., Naval Administrations, 1827 to 1892: the Experience of 65 Years (London, 1827)

Hamilton, C.I., The Making of the Modern Admiralty: British Naval Policy-making, 1805-1927 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011)

Hinde, Wendy, George Canning (London: Purnell, 1973)

House of Commons Journal, 1828, 1831-2

Knight, Roger, ‘Sandwich, Middleton and dockyard appointments’ Mariner’s Mirror, 57, 1971, pp.175-192

Knight, Roger, Britain against Napoleon: the Organization of Victory, 1793-1815 (London: Allen Lane, Penguin, 2013)

Knight, Roger, William IV: A King at Sea (London: Allen Lane, Penguin, 2015)

Lambert, Andrew, The Last Sailing Battlefleet: Maintaining Naval Master, 1815-1850

(London: Conway Maritime Press, 1991)

Lambert, Andrew, ‘Preparing for the Long Peace: The Reconstruction of the Royal Navy, 1815-1830, Mariner’s Mirror, 82, 1996, pp.41-54

Lambert, Andrew, ‘Politics, administration and decision-making: Wellington and the Navy, 1828-30’ in C.M. Woolgar (ed.) Wellington Studies IV (Southampton: Hartley Institute, University of Southampton, 2008) pp. 185-239

Marshall, John, Royal Naval Biography 4 vols. (London, 1823-35)

Morriss, Roger, Cockburn and the British Navy in Transition: Admiral Sir George Cockburn 1772-1853

(Exeter: Exeter University Press, 1997)

Morriss, Roger, Naval Power and British Culture, 1760-1850: Public Trust and Government Ideology (Aldershot, Hants: Ashgate, 2004)

Morriss, Roger, The Foundations of British Maritime Ascendancy: Resources, Logistics and the State, 1755-1815 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011)

Muir, Rory, Wellington: Waterloo and the Fortunes of Peace, 1814-1852 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2015)

Parnell, Sir Henry, On Financial Reform (London: John Murray, 1830)

Rose, Susan, England’s Medieval Nay, 1066-1509: Ships, Men and Warfare (London: Seaforth, 2013)

Strachey, Lytton and Roger Fulford, The Greville Memoirs, 1814-1860, vol. I (London: Macmillan, 1938)

Vesey-Hamilton, Sir Richard, Journals and Letters of Admiral of the Fleet Sir Thomas Byam Martin (London: Navy Records Society, vols. 12, 1898,19, 1900)

Ziegler, Philip, King William IV (London: Collins, 1965)

References

- Anon, ‘Commander’, p.9

- Briggs, p.8

- Anon, ‘Commander’, p.72

- Briggs, p. 9

- Briggs, 11)

- Lambert, Battlefleet, chapter 1

- Lambert, ‘Reconstruction’, p.45)

- Morriss, Cockburn, p.172

- Bonner-Smith,pp.154-5

- Rose, pp. 47, 50

- Knight, Britain against Napoleon, pp.109-117

- Knight, ‘Dockyard Appointments, pp.90-2

- Knight, Britain against Napoleon, p. 221

- Marshall, vol.1, p.397

- Vesey Hamilton,,II, p.386

- Hinde, p.443

- Muir, pp. 286-7

- Strachey and Fulford, I, p.173

- Morriss, Cockburn, p.165

- Aspinall, Letters of George IV p. 264

- Aspinall, Letters of George IV, p.65

- Bonner-Smith, p.156

- Morriss, Cockburn, p.166

- Lambert, ‘Wellington and the Navy’, pp.185-239

- NMM, COD/13/1, 18 Jun 1827)

- NMM, COD/13/1, 16 Oct 1827

- NMM, COD/13/1, 19 Jun 1827

- Muir, pp.297-8

- NMM, OGL/13/27, 28 Feb 1828

- NMM, STO/4, 35 letters, 1827-8

- R.S. Spencer, Clarence’s private Secretary to Stopford, STO/4, 29 Dec 1827)

- NMM, GUN/8

- Ziegler, p.141

- Morriss, Cockburn, pp.169-172

- Aspinall, Corr. George IV, III, pp.412-415

- HCJ, vol. 83, 1828, p.76)

- Hamilton, p.75

- Morriss, Cockburn, p.187

- HCJ, 1831-2, p.104, 15 Feb 1832

- Parnell, p.141

- Parnell, p.150

- Parnell, p.152

- Parnell, 143, 146

- Vesey Hamilton, vol. III, p. 377

- Parnell, p.169

- Morris, Naval Power, pp. 248-252