Please extend a hearty welcome to Dr Jessica Floyd, who is joining the staff of the website. In this post, she discusses her work and some of what she’ll be looking at in her series Sea Chanteys.

Please extend a hearty welcome to Dr Jessica Floyd, who is joining the staff of the website. In this post, she discusses her work and some of what she’ll be looking at in her series Sea Chanteys.

As this is my first post for Global Maritime History, I thought that I would begin by laying out a little about myself, my interests, and how I came to the sea chanteys of the early modern sailor. My dissertation work investigated bawdy narratives of unexpurgated sea chanteys and the path that I took to arrive at such a topic attests, in many ways, to the concept of how an academic’s life outside of the stacks of books, papers, and lectures often intersects with his or her research interests and initiatives or forces him or her down a particular path which arrives at his or her object (s) of focus.

My dissertation work was partially the result of a long fascination with the erotic. As a young girl, my room was littered with books like The 120 Days of Sodom, The Story of O, and Venus in Furs. It was not until I made it to an undergraduate literature course on the seventeenth century, at Towson University, that I realized (with the help of Dr. H. George Hahn III), that I could focus my entire academic career on that material, however. It was in that course that I learned of the work of John Wilmot, the Second Earl of Rochester and he, along with other Restoration rakes, became my focus and my obsession throughout the remainder of my undergraduate and master’s degree careers. As a young student, I was elated to learn that academia gave me a space to explore sex and sexuality and that, much to my surprise, the world has had quite a colorful and verbose relationship with the erotic. By the time that I made it to my master’s program at the University of Maryland, College Park, however, my research had become a little stale and I was pressed with the realization that I would need to develop something for a final capstone project. I was still passionately in love with the Restoration rakes, especially Rochester, but I needed something new to pursue.

In my family, we discuss everything and the trouble I was having with finding a topic for my master’s capstone project was no different. There was never a taboo subject in my household and, thus, my whole family was always aware of what I was studying. In fact, one question always posed during a late Friday night or Sunday-dinner gathering focused on what bawdy or salacious poem or play I had discovered or analyzed that week. One night, after the whole family had enjoyed several drinks, my dad asked me if I had ever considered sea chanteys. Of course, I had never heard of sea chanteys. With a wry smile and without skipping a beat he proceeded to sing, in his merry baritone voice, “Barnacle Bill the Sailor.” The lyrics of the song were so much like the erotic, Restoration poetry I had read that I knew instantly that I had to pursue the topic further. There was so much laughter in the room, there were so many provocative innuendos, satirical possibilities, and complex metaphoric constructions that I was overcome with excitement with the prospect of what my investigation might uncover.

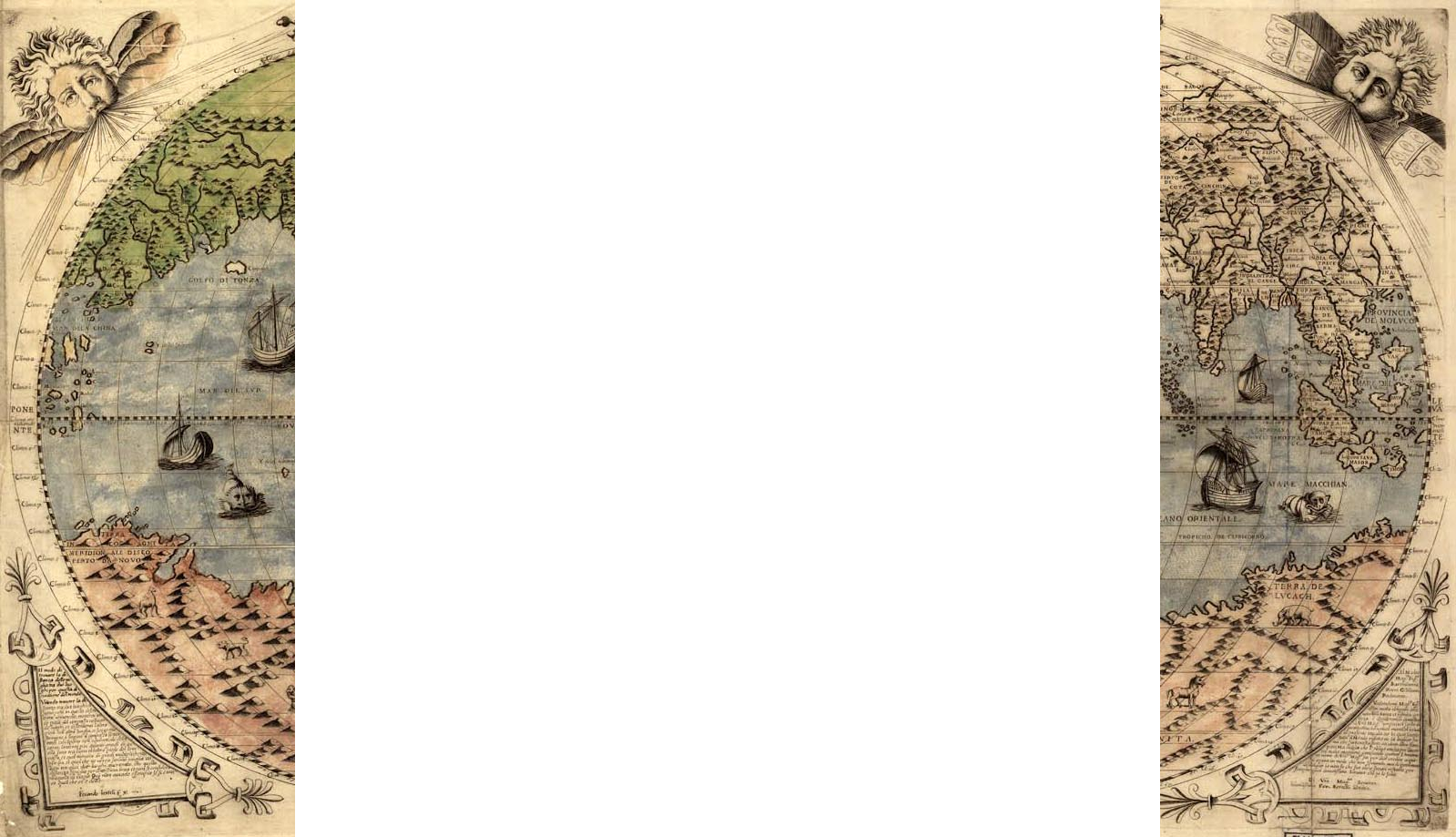

I took my father’s advice and began research for my capstone project; however, I realized, very quickly, that the possibilities the genre produced were not only massive, but that a capstone project would not allow the space or the depth to adequately investigate or treat the genre. It only took a few early stabs at research to realize that very little to none of the material that was collected, collated, and published was bawdy and salacious as I had come to expect from the song that my father shared with me. With what little I knew of sailors, which was all culturally constructed, I had expected to find rough, coarse language, curse-words, slang, and an abundance of sex, especially sex that transgressed into the homoerotic. I became obsessed with finding what I knew to be the “true” and “authentic” sailor chantey which must include bawdy and salacious material similar to what I found in Restoration poetry, prose, and drama. I was quickly overwhelmed. The early materials I gathered sat in a far corner of my office at home for several years, gathering dust, before I began considering the prospect of a PhD program. I finally applied to the Language, Literacy, and Culture PhD program, funny enough, after a long night of drinking with colleagues (see a theme here?). I talked about this passion and curiosity for the genre that had been stoked and then left to fizzle out, unsure of how to proceed. Once I was accepted into the program at UMBC, I immediately launched into the research on the genre, knowing next to nothing about sailors or the early modern maritime world. All of my early research and focus had dealt with the early modern world on land and I had yet to explore the water ways that were so much a part of shaping the landscape even as it is now. The sea chanteys, in a way, ultimately became a way through which I continued with my passion for erotic literature but were also a mode through which I nurtured a newfound fascination with the historical world of Jack Tar. Because of what he sang, I became enthralled with the prospect of understanding who he was, what he thought, how he lived, and what his world was like. I began to wonder if the sea chanteys were a place through which a scholar might investigate the world of the deep sea sailor, through his own language, and a further historical object through which we might conjure the past. My final dissertation work confirmed this for me and my ultimate intent is to not only preserve the songs of the sailor but also to propel this genre back into scholarly focus as, what I argue, is a way through which scholars might place their fingers on the pulse of the maritime world.

This will be cool.

Have you already published anything on sea chanties?

Hi there! I have not yet, but I am in the process of getting something together to publish.

Let me know when you do, my brother in law is a retired seaman and a chantey singer and I’m sure it would interest him.