Manikarnika Dutta completed her MSc in the History of Science, Technology and Medicine on a Wellcome Trust Master’s Studentship at the University of Oxford. She has recently defended her DPhil thesis that was part of the Wellcome Trust funded ‘From Sail to Steam’ project at Oxford. Her research examines the health and sanitary regulation of European seamen in colonial Indian port cities, integrating the history of health, imperial governance, maritime exchange and public policy in the British Empire. She was awarded the Taniguchi Medal (2018) by the Asian Society for the History of Medicine for the best graduate essay submission. She tweets at @DManikarnika.

Manikarnika Dutta completed her MSc in the History of Science, Technology and Medicine on a Wellcome Trust Master’s Studentship at the University of Oxford. She has recently defended her DPhil thesis that was part of the Wellcome Trust funded ‘From Sail to Steam’ project at Oxford. Her research examines the health and sanitary regulation of European seamen in colonial Indian port cities, integrating the history of health, imperial governance, maritime exchange and public policy in the British Empire. She was awarded the Taniguchi Medal (2018) by the Asian Society for the History of Medicine for the best graduate essay submission. She tweets at @DManikarnika.

In late eighteenth-century Britain, the christian churches started taking a renewed interest in helping seamen out of their perceived depravity and deplorable living condition. Their sympathy for seamen increased manifold following the latter’s heroics in the Napoleonic Wars. In unreserved acknowledgment of naval and merchant seamen’s contribution to the military and commercial activities of the British Empire as well as transporting preachers to distant lands, the clergy took it upon themselves to improve seamen’s lives. Missionaries designated as Seamen’s Chaplains started preaching the virtues of temperance and righteousness to seamen. Several societies dedicated to protecting sailors from crimps and disease came up in the early nineteenth century. They generated much enthusiasm by seeking to involve common people in religious activities and collaborating with the state to help seamen on shore. The Admiralty aligned itself to their relief measures in British port cities by sanctioning vessels to be used as floating chapels and seamen’s libraries, and supporting daily preaching, prayers and religious tract distribution on ships. The main concern was keeping seamen off public houses and brothels while they were ashore. Special buildings designated as Sailors’ Homes came up in a number of port cities across the Empire to shelter seamen who would have otherwise spent their leave in the company of drunkards and prostitutes,

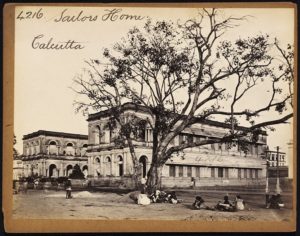

After London and New York, a Sailors’ Home was established in Calcutta, capital of British India, in 1837 under the aegis of the Calcutta Seamen’s Friend Society. The colonial government permitted use of a large old building on Flag Street where once stood Harmonican Tavern – a famous night haunt in the late eighteenth century. The Home was to provide seamen with ‘comfortable lodging, plain food, innocent recreation, and religious guidance.’ The printed programme for the inauguration ceremony noted the intention to ‘suppress crimping and all the evils arising from it to which owners, commanders, officers and crews are subject in the port of Calcutta.’ The manifesto shows that residents were not allowed to bring liquor from outside. The Home had a bar that would not sell more than two glasses of liquor daily to individuals, and reserved the right not to sell any liquor if the customer seemed to be inebriated. The House Committee would expel seamen if found to have exceeded their quota of drinking. The Committee also gave them certificates of character, commending them for not visiting local grog shops and prostitutes. This letter of recommendation increased seamen’s chances of being accommodated in similar institutions in other port cities. In every annual report, the authorities congratulated themselves on successfully eradicating seamen’s drinking impulse and making them better men. However, at least one official went on record staying that the benevolent institution achieved precious little.

Rev. Thomas Atkins was appointed the Sailors’ Home’s Superintending Secretary within ten days of his arrival from Australia in 1838. He was also made the Minister of the Bethel after a few weeks. He later wrote a memoir, where he ruefully reflected upon his work in Calcutta. Apparently one of the benefactors of the Sailor’s Home was a seller of spirits, beer, and wine, and about half of the management committee members were directly or indirectly involved in the liquor trade. They encouraged drinking at the Sailors’ Home, even if in a small quantity, to make seamen crave more liquor. They made no real effort to stop resident seamen from visiting public houses and becoming drunk. Atkins was often awakened by the noise of drunk seamen scaling walls to enter the Sailors’ Home on their return from punch houses and brothels. Such poor management had made the entire endeavour a curse rather than a blessing for seamen and ship owners.

Atkins saw himself as a ‘licensed victualler,’ whose main responsibility was to monitor the store of ‘beer, in barrels and bottles; wines – port, sherry, and claret, in dozens; spirits – brandy, gin, and rum, in large quantities.’ He notified the general committee that bartenders sold sell more liquor than stipulated to residents and were sometimes caught stealing bottles from the store at night. He proposed to discontinue the sale of liquor to avert a possible breakdown of the charity. When the committee rejected his proposal, a humiliated Atkin resigned from his position after having served for 12 months. At the next meeting of the committee, he raised the demand of total abstinence at the Sailors’ Home. His repeated entreaties led to an enquiry, conducted by ‘traffickers in alcoholic drinks,’ which ultimately ruled in favour of selling liquor. Two other members of the clergy associated with the Sailors’ Home resigned in protest. The disjuncture between intention and practice is very evident in Atkins’ reminiscences. Yet, the annual reports of the Sailors’ Home or proceedings of the annual meetings never referred to any disagreement over how the institution was run, or any allegation of mismanagement against the governing committee.

Several other observers were critical of the Sailors’ Home’s early failure to deliver moral progress to seamen. Periodicals reported that in the 1840s, young people leaving England full of hope and aspiration would bury their dreams in Lal Bazar and return home, if they did, with ‘heart contaminated, his principles perverted.’ Personal narratives such as Atkins’ or Montague Massey’s, which called the Sailor’s Home a ‘crying scandal’ in the 1850s, show the lofty ideals of religious humanitarianism were seldom realised in practice, especially in places where public knowledge and involvement in such activities were few and far between. The Calcutta Seamen’s Friend Association had claimed in a pamphlet published on the occasion of the Sailors’ Home completing a decade that within its first 18 months the institution was able to orchestrate closure of all but one of the punch-houses in the vicinity, and the one still open had only a single occupant. Yet, after ten years, scores of punch-houses were found to exist near the Sailors’ Home. They owners made so much profit that they did not hesitate paying up to three rupees per day as licence duty. The minimum licence fee paid by a punch-house keeper in Calcutta was 939 rupees or £93.18s a year, which was more than what attorneys in England paid and whined about. Evidently, the Sailors’ Home was not managed as efficiently as it should have been. The institutions in India lasted longer in comparison with their counterparts elsewhere in the British Empire, but they were also plagued by more criticism. There was an apparent lack or rather suppression of debate within the religious administration. The overdependence on local merchants for financial support, since the colonial state would not entangle themselves in religious matters, seemingly boomeranged as sponsors pushed agendas of their own. If we are to believe Atkins, the winners were the seamen, who were able to find both liquor and a comfortable resting place away from home.

Further reading

Atkins, Thomas. Reminiscences of Twelve Years in Tasmania and New South Wales, Norfolk Island and Moreton Bay; Calcutta, Madras and Cape Town; The United States if America and the Canadas. Malvern: Advertiser Office, 1869.

Kennerley, Alston. “British Merchant Seafarers and Their Homes, 1895-1970.” International Journal of Maritime History 24, no. 1 (June 2012): 115-146.

Kverndal, Roald, Seamen’s Missions: Their Origins and Early Growth. Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 1986.