Jamestown Fort and Colony Approximately 1620s

In July 2003, historian and author, Adam Goodheart’s Op-Ed, ‘The Ghosts of Jamestown’ ran in The New York Times. Goodheart happened to be driving by the Jamestown National Historical Park when the U.S. Supreme Court majority struck down a then Texas law prohibiting same sex intercourse between consenting adults.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote of the ruling, “Liberty protects the person from unwarranted government intrusions into a dwelling or other private places. In our tradition the State is not omnipresent in the home. And there are other spheres of our lives and existence, outside the home, where the State should not be a dominant presence. Freedom extends beyond spatial bounds. Liberty presumes an autonomy of self that includes freedom of thought, belief, expression, and certain intimate conduct. The instant case involves liberty of the person both in its spatial and more transcendent dimensions.”2

Historic Jamestowne Source Virginia.org

“Cornish” was Richard Williams alias Cornish, an early seventeenth century British mariner who in August 1624 was Master of a British merchant ship called the Ambrose.4 I have been researching Cornish, full time, for the past five years for a book I am writing about him.

Why, after hearing the news, would Goodheart drink to Cornish?

Witnesses before the Council and Governor Source British Heritage Travel

(Modern spelling and McIlwaine’s edits used).

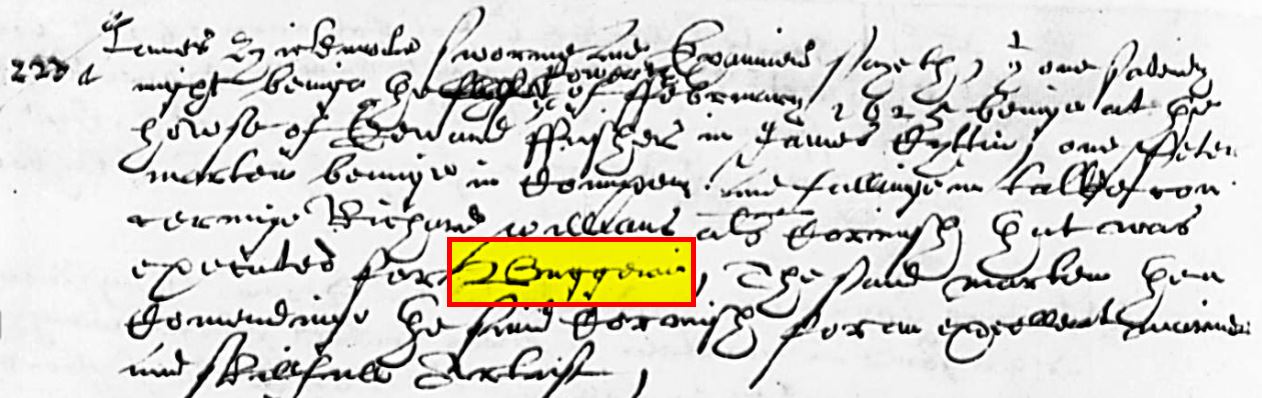

At this first mention of Cornish’s trial in the historical record the official charge against Cornish is not given but the charge is alluded to in later testimony. Though also omitted by McIlwaine in 1917 and replaced with “[unnatural crime]” it is testified that the charge against Cornish was “Buggerie”.5

The word “Buggerie” in the original 1626 document. James Hickmote’s testimony. Source Library of Congress, Image 238. Minutes of the Council and General Court.

A School History of the United States by David B Scott 1879 pg 33

Supreme Court Justice Kennedy, based on the amicus briefs studied before ruling on that 2003 case, wrote of America “…it should be noted that there is no longstanding history in this country of laws directed at homosexual conduct as a distinct matter. Beginning in colonial times there were prohibitions of sodomy derived from the English criminal laws passed in this first instance by the Reformation Parliament of 1533. The English prohibition was understood to include relations between men and women as well as relations between men and men…Nineteenth century commentators similarly read American sodomy, buggery, and crime-against-nature statutes as criminalizing certain relations between men and women and between men and men…according to some scholars the concept of the homosexual as a distinct category of person did not emerge until the late 19th century…Thus early American sodomy laws were not directed at homosexuals as such but instead sought to prohibit nonprocreative sexual activity more generally. This does not suggest approval of homosexual conduct. It does tend to show that this particular form of conduct was not thought of as a separate category from like conduct between heterosexual persons. Laws prohibiting sodomy do not seem to have been enforced against consenting adults acting in private. A substantial number of sodomy prosecutions and convictions for which there are surviving records were for predatory acts against those who could not or did not consent, as in the case of a minor or the victim of an assault. As to these, one purpose for the prohibitions was to ensure there would be no lack of coverage if a predator committed a sexual assault that did not constitute rape as defined by the criminal law….In the 19th century in America, “Under then-prevailing standards, a man could not be convicted of sodomy based upon testimony of a consenting partner, because the partner was considered an accomplice. A partner’s testimony, however, was admissible if he or she had not consented to the act or was a minor, and therefore incapable of consent” (Kennedy 2003, np).

Replicas of The Discovery The Godspeed and The Susan Constant moored at the Jamestown National Park docks in Jamestown Virginia

Jamestown Sydney King Paintings US National Park Service

And crucially, early Virginia’s justice was different from English Common Law because of those precedents.

Had Couse’s case against Cornish been tried in England, it would have come before the Court of Admiralty and not a Council. So, Cornish’s trial must have been a proceeding that anyone then in the colony dealing in merchant trade but especially mariners followed closely. Everyone would have been interested in the Council and Governor’s verdict but sailors would have followed this trial to see how charges brought against English mariners, even a Master of a ship, for crimes alleged in waters in the New World, would be adjudged before the non-Admiralty Jamestown Council.

Walter Mathew was the only other person besides Cornish and Couse aboard the Ambrose on the day in question. Mathew, was, according to the record, also the only other person besides Couse to testify in the trial. A month after Couse testified,

Page 49 Source Richard of Jamestown by James Otis 1910

(Modern spelling and McIlwaine’s edits used).

After Walter Mathew testified Richard Williams alias Cornish was found guilty of sodomy. Though the Minutes do not provide the execution order, from testimony that follows we know that Cornish was hanged.12

The Colony’s leadership’s word was final. It was against the law for a colonist to speak publicly against the Jamestown Governor’s or Council’s rules, orders or verdicts and though it was unusual, doing so was even punishable by death.

Yet, a year after Cornish was found guilty somebody spoke out. Also before the Governor and Council in James Cittie, on December 12, 1625 William Foster testified that…he demanded of a Mr. Nevell why Master Cornish was hanged. “Nevell answered [sic. describing Couse] he was hung for a rascally boye wrongfully, And that he hath heard Mr Nevell say so divers tymes” (McIlwaine 1916, 340).

Page 83 Source Richard of Jamestown by James Otis 1910

In the testimony that followed, Jeffery’s reaction to learning of his brother’s execution was described again, this time by,

(Modern spelling and McIlwaine’s edits used).

One of the colonial Council who, along with Governor Wyatt and the other Council members, oversaw Richard Cornish’s sodomy trial, was Virginia Company Treasurer, George Yeardley. He had most recently served as Governor of the colony and would once more after Wyatt. His second appointment began in 1624. The Governor after Yeardley’s second tenure was John Harvey who “took advantage of the position to advance his private interest “by foule and coveteous ways,” and in kind pardoned other corrupt Council members because, perhaps referring to Governor Yeardley, Governor John Harvey “…found his delinquencies to have been in imitation of “the example of a former governor who passed unquestioned for many notable oppression”” (Morgan 1971, 191). Indeed, when Yeardley’s term as governorship ended he was expected to give up his tenants to the incoming governor. He did not. In fact of Yeardley “…the records contain accusations against him of detaining servants belonging to other planters and of keeping as a servant a young man whose relatives had paid his way” (Morgan 1971, 192). Governors were among the most powerful of the Colony’s leadership.

Three weeks later more about Jefferey Cornish’s reaction is recounted. Jefferey must not have been known to this next witness personally since Avenlinge, here, simply refers to Jefferey as “one who came aboard”.

The Governor and Council had heard enough.

Pillory Page 134 Source Richard of Jamestown by James Otis 1910

Yet, two years after Cornish hanged, a year to the day after Nevell’s punishments were ordered, and despite the example made of Nevell by his having been punished, men continued to speak out.

The Council and Governor heard testimony that at Edward Fisher’s house in James City, Jamestown, quoting McIlwaine,

Masten was indeed running a real risk speaking for Cornish. He was a servant known as a Duty Boy, an apprentice sailed to the colony from England, aboard the ship, Duty. Taken off the streets of London, many of the Duty Boys were petty criminals or worse. From the Mayor of London’s point of view sending them to Virginia got rid of them. The colonial leaders saw it as a boon, as well, receiving poor delinquents nobody would miss. Young street criminals would have little social standing practically making them young men without rights, and youths easier to take and keep, thereby giving Virginia planters young healthy servants. Once Duty Boys arrived at the colony, “They were bound to serve for seven years under any planters who would pay ten pounds apiece for them. After their seven years’ service, they were to be tenants bound for another seven years. If, however a Duty boy committed a crime at any time during the first seven years, his term as a servant was to begin again for another seven years.”13

Work In the Colony Source Unknown

There was more testimony about what was said at Edward Fisher’s house two years after Cornish hanged.

The Governor and Council ruled.

14 (Modern spelling and McIlwaine’s edits used).

Page 86 Source Richard of Jamestown by James Otis 1910

In that 2003 New York Times Op-Ed, Goodheart, “…had a date the other night with a guy who has been dead for almost 400 years. His name was Richard Cornish, and the last time he got involved with another man, he was executed for his crime. That was at Jamestown, Va., in 1624, and his case was the first recorded sodomy prosecution in American history” (Goodheart 2003, np).

But, vague though it is, mention is made of another earlier Virginia colony sodomy trial that occurred two years before Cornish’s, despite none of its trial transcripts existing today. While short, the account depicts, too, how justice proceeded in the colony. One of the founders of Jamestown, Captain John Smith in his Travels and Works, wrote that in June 1622 in Jamestown’s General Assize Court “…where not fewer than fifty civil, or rather uncivil actions were handled, and twenty criminal prisoners brought to the bar; such a multitude of such vile people were sent to this Plantation…three of the foulest acts were these: the first for the rape of a married woman, which was acquitted by a senseless Jury; the second for buggering a sow, and the third for sodomy with a boy, for which they were hanged.”15 (Modern spelling used).

As he is remembered today, he is also acknowledged, “Records don’t show whether Richard Cornish felt like a martyr almost 400 years ago as he stood on a Jamestown gallows with a rope around his neck. But he was adopted as one by the [sic. College of ] William and Mary Gay and Lesbian Alumni Association. GALA and a number of activists and historians recognize Cornish as the first man prosecuted and executed for homosexuality in the British North American colonies.”16

This article goes on to explain that GALA raised money for an endowment and created a scholarship in Cornish’s name. It still exists today. Of the College of William and Mary’s GALA “…they say it doesn’t matter that records and some historians suggest that Cornish’s actions weren’t victimless – that he committed forcible sodomy along with what today could be called sexual harassment. Whether Cornish, a ship’s captain, was a hero or a heel depends on who’s looking.” (Bowers 2007, np).

Even in the years immediately following Cornish’s hanging, it depended on who was looking, and as we’ve read, people were doing more than looking.

Still from Sky 1 TV show, Jamestown

According to the testimony, despite the risks they were facing, after learning of Cornish’s demise William Foster must have been stunned in order to demand of Edward Nevell ‘what happened?!’ Cornish’s brother was so shocked to learn that Richard had been executed, and for sodomy, that Jefferey Cornish vowed before others that he would kill the Governor. Nevell, while explaining what happened, claimed the execution was by “a scurvy boy’s means” referring to Couse and said, ‘no other came against Cornish’. A year after his execution at least these three men, at risk to their limbs, liberty, and lives made it known that they believed Cornish’s execution was unjust.

Yet the year after, two years after Cornish hanged, it continued. Risking having another seven years added to his servitude, before a group of people Peter Masten questioned Cornish being found guilty of the charges because Masten thought Cornish an “excellent man” and mariner. Thomas Hatch, as testified, stated explicitly “Cornish was put to death wrongfully”. Hatch was warned of the serious personal risks he was facing saying publicly that Cornish should not have been hanged, and Hatch continued, responding that he knew the risks. He was willing to be hanged to say out loud what, according to the testimony, was weighing on his conscience because it was something with which he was still struggling two years after Cornish’s demise.

Based on their individual personal knowledge of Cornish at least these five men, under the jurisdiction of the exact same Jamestown colonial laws and leaders that executed Cornish, at real peril, spoke publicly against Couse’s accusation and against Cornish’s execution – something they perceived as very wrong.

Of other instances in the early American historical record of colonists’ experiences after being found guilty of sodomy,

In England, after the 1860’s, “A committee advising the British Parliament recommended in 1957 repeal of laws punishing homosexual conduct…Parliament enacted the substance of those recommendations 10 years later” (Kennedy 2003, np).

Interestingly, in the United States, “It was not until the 1970’s that any State singled out same-sex relations for criminal prosecution, and only nine States have done so…Over the course of the last decades, States with same-sex prohibitions have moved towards abolishing them. The issue is whether the majority may use the power of the State to enforce these views on the whole society through operation of the criminal law. “Our obligation is to define the liberty of all, not to mandate our own moral code.” Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey….Had those who drew and ratified the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth Amendment or the Fourteenth Amendment known the components of liberty in its manifold possibilities, they might have been more specific. They did not presume to have this insight. They knew times can blind us to certain truths and later generations can see that laws once thought necessary and proper in fact serve only to oppress. As the Constitution endures, persons in every generation can invoke its principles in their own search for greater freedom (Kennedy 2003, np).

On February 8, 1625/26, after his execution, Cornish’s accuser, William Couse, was given his choice of Virginia Colony masters to serve, Captain West or Captain Hamor. Couse was evidently staying on in Jamestown. He chose Hamor. Nothing else of Couse’s life afterward is known.17

We know that the Minutes as they exist today are not the complete original Jamestown Council Minutes.18 Some pages have been lost.19

So if the record once included it, no record exists today of Richard Cornish having defended himself at trial. We have no record of his voice in response to Couse’s accusation.

© 2020 Arlene Spencer. All Rights Reserved.

- McIlwaine, H.R. 1917. “Minutes of the Council and General Court 1622-1624.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 25, No. 1 (Jan.): 61.

- Kennedy, The Honorable Supreme Court Justice Anthony. John Geddes Lawrence and Tyron Gardner, Petitioners v. Texas. Court Opinon. 2003. Legal Information Institute. Cornell Law School. June 26, 2003. https://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/02-102.ZO.html. Last visited June 1, 2020.

- Goodheart, Adam. 2003. “The Ghosts of Jamestown.” New York Times, July 3, 2003, np. https://www.nytimes.com/2003/07/03/opinion/the-ghosts-of-jamestown. Last accessed April 26, 2019.

- Minutes of the Council and General Court of Colonial Virginia edited by, H.R. McIlwaine. 1924. Richmond. Virginia State Library, 34.

- Image 238. Virginia General Court, 1622-29, Cases, with Minutes. 1625/26.The Thomas Jefferson Papers at the Library of Congress. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/mtj8.064_0002_0573/?sp=238. Last visited May 24, 2020.

- Crompton, Louis. 1976. “Homosexuals and the Death Penalty in Colonial America.” Journal of Homosexuality, Vol. 1 (3): 277-278.

- Proud Heritage, Vol. 2. Chuck Stewart, Editor. 2015. Santa Barbara. ABC-CLIO, LLC, 364.

- Cocks, H.G. 2017. Visions of Sodom Religion, Homoerotic Desire, and the End of the World in England C. 1550-1850. Chicago and London. University of Chicago Press, 112.

- Swindler, William F. 1980. “Book Review of Legislative Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia and Minutes of the Council and General Court of Colonial Virginia”. William & Mary Law Review Vol. 22[2]:325.

- The List and Index Society. 1969. Oyer and Terminer Records (HCA I), Vol. 45. London. Swift (P&D) Ltd., 3.

- Konig, David Thomas. 1982. “”Dale’s Laws” and the Non-Common Law Origins of Criminal Justice in Virginia.” The American Journal of Legal History 26, No. 4 (Oct.): 357.

- McIlwaine, H.R. 1916. “Minutes of the Council and General Court 1622-1624.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 24, No. 4 (Oct.): 340.

- Morgan, Edmund S. 1971. “The First American Boom: Virginia 1618 to 1630.” The William and Mary Quarterly 28, No. 2 (Apr.): 184

- McIlwaine, H.R. 1917. “Minutes of the Council and General Court 1622-1624.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 25, No. 2 (Apr.): 121-122.

- Smith, John. 1910. Edward Arber, Editor. Travels and Works of Captain John Smith, Part II. Edinburgh. John Grant, 683.

- Bowers, Mathew. 2007. “Gay, lesbian group honors controversial Jamestown figure.” The Virginian-Pilot, March 12, 2007, np. https://www.pilotonline.com/news/article_a8f2ff75-6ef3-5969-99a8-b654cda845b5.html. Last accessed April 26, 2019.

- McIlwaine, H.R. 1914. “Minutes of the Council and General Court 1622-1624.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 22, No. 1 (Jan.): 3.

- Spencer, Arlene. 2019. “New Evidence: Was Thomas Weston, Seventeenth Century London Merchant among the First to Sail Fish to Virginia’s Starving Colonists?” Global Maritime History. 25 February 2019. http://globalmaritimehistory.com/thomas_weston_merchant/. Last visited May 19, 2020.

- McIlwaine, H.R. 1913. “Minutes of the Council and General Court 1622-1624.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 19, No. 2 (Apr.): 114.