Susan Constant, Godspeed and Discovery at Jamestown Docks – May 2008.

Photo by Bill Barber Creative

For the past four years I have researched early seventeenth century English ship’s Master, Richard Williams alias Cornish, or Richard Cornish, full time, to inform an historical non-fiction book I am writing about the mariner.

I first learned of Cornishe while reading that his was one of the earliest executions in Jamestown. Curious to know more I looked further into his case in the Minutes of the Council and General Court, (hereafter MCGC or Minutes), the earliest historical legal record of the Jamestown colony in existence today.1

The historian who first transcribed the MCGC, H.R. McIlwaine, finally making it accessible to the public, published two different versions. The first was serialized from 1911 to 1923 and the second was published in 1924 as a book.2

In the January 1913 issue, where a transcription should have been, McIlwaine instead noted in brackets that he omitted from publication the minutes of a deposition that existed in the original historical record.3 In the following issue, dated April 1913, he did it again. The minutes of existing historical testimony once more was not published.4

Ship with Sails Furled and Arrow Pointing to the Right by Master W with the Key Ship engraving on paper dated 1475-1485.

It happens that these two records McIlwaine censored pertained to one legal case, the 1624 accusation by sailor, William Couse, of “buggerie”,5or sodomy, against ship’s Master, Richard Williams alias Cornishe, he said occurred aboard the Ambrose while at anchor in the James River.6

About one hundred thirty-five years after the last of the Virginia Colony’s earliest court records were written down, ““…a young …Thomas Jefferson began collecting manuscript and… Later he remembered that he “spared neither time, trouble, nor expence” to gather [sic. records] that were “on the point of being lost, as existing only in single copies in the hands of careful or curious individuals, on whose deaths they would probably be used for waste paper.” The collection of legal and legislative volumes Jefferson gathered came from various sources. They were gifts, loans, and purchases… Jefferson rescued one volume of Virginia laws (volume 9, one of two “Charles City” manuscripts) from a tavern where it had been, as he warned, regarded as “waste paper” by tavern-goers who used it to scribble on.” He wrote that some of the manuscripts were “so rotten, that, on turning over a leaf, it sometimes falls into powder.””7

The documents Jefferson collected included the MCGC: what remains today of the Jamestown colony’s first judicial and executive or legal records.8

Judicial and executive proceedings were carried out in accordance with the practices of the Anglican Church but only in the spirit of the British law practiced and administered at that time, at home in England. Of jurisprudence typical of early English colonies “As revealed by the Journals, [sic. the MCGC] the kind of justice administered during these early decades was pragmatically simple.” For example, it was not until 1680, nearly seventy years after the founding of Jamestown, that attorneys were in regular practice in the colony.9

While early Jamestown was not as pious in its Anglican beliefs as early Plymouth’s adherence to Puritanical Separatism, Jamestown was a religious colony. British civic or social norms were Anglican, probably then still guided by Elizabeth I’s Protestant British Bishop’s Bible, and strictly adhered to. There was no separation of Church and State. Since the colony’s founding, it was improper and a punishable offense to miss church and punishments were issued.

Print of Captain John Smith landing in Jamestown Virginia 1607. From The Story of Pocahontas and Captain John. 1906 Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

The colony’s leadership was comprised of two branches. “…the Council was the General Court, for the membership of the judicial panel was drawn from the appointive upper chamber of the colonial assembly.”10 At this time, the second branch, the Governor was appointed by the Virginia Company of London (the corporation that founded and operated the colony). “In the period covered… the Council had not begun to find it necessary to hold separate meetings for the transaction of its several kinds of business. In the minutes… executive and judicial items are freely intermingled, the latter, very naturally, predominating, since as a court the Council, the governor acting with it, had both original and appellate jurisdiction, and a great many cases arose; whereas the governor as an executive did not find it necessary except occasionally to call on his Council for advice. …Though the charter of the Virginia Company of London was abrogated in 1624, the form of government which the company had evolved went on, the king taking the place of the company. The three-fold functions of the Council – executive, judicial, and legislative – continued.”11

In fact, the historical record contained in the MCGC contributed to the earliest conceptions of the American legal system. Jefferson, the primary author of the Declaration of Independence, studied the MCGC noting the colonial criminal sentencing of those early decades of Jamestown. Jefferson included Cornishe’s case in a list he himself wrote of different kinds of crimes and the resulting sentences the Jamestown Council ordered as an “…outline for his Bill for Proportioning Crimes and Punishments, written in 1777.” Jefferson “…later employed this list in preparing Query XIV of the Notes on Virginia, copying it almost verbatim in his discussion of the revised code.”12 13

Wives for the Settlers at Jamestown, from United States a History, by John Clark Ridpath 1893.

As it exists, today, only a part of the original record, the Minutes start fifteen years after the founding of the colony, immediately after the Indian Massacre of 1622 “and extend over a period during which we have but little detailed information in regard to the inner life of the Colony. We know something of public events, of the war with Indians and the actions of Assembly, but very little in regard to the people themselves.”14

To understand something of those people the last thing students interested in early Virginia needed was history being censored. By editing out historical testimonies McIlwaine did not really omit as much as he prognosticated, given norms common in America in 1913. Indeed, he had censored the historical record but McIlwaine also alerted his readers to the fact that he had done so. So, why did McIlwaine censor the historical record?

Today, Cornishe is believed to be the first person executed on the North American continent for the crime of “Buggerie” or sodomy15 16. The crime Cornish committed is believed by others to have been rape17. The hearing records do not state what Cornishe was charged with but testimony, a year later does read, “…one Peter marten beinge in Compeny and fallinge in talke concerninge Richard Williams als Cornish that was executed for Buggerie,…”18. It is also considered not uncommon for its time, “…the trial of Richard Cornish usefully illustrate the commonplace nature of a homosexual invitation in early seventeenth-century America.”19

Bottom corner of Index pg 549, McIlwaine Ed Mins of the Council and Gen Court, Richmond, VA 1924.

In place of the omitted historical testimonies in the 1913 issues, when he described the content of the skipped records as relating “unnatural crime” or as being “unprintable”20 or deeming it “not fit for publication”21 McIlwaine actually articulated the explanation as to why he censored these two records. His wording might sound judgemental, prudish or his redaction seem unethical to us, today, but it was not just societal conventions that led to the omission. The United States Postal Service, following the 1873 Comstock Act and its focus in particular on prohibiting the dissemination of “obscene acts”, made mailing a publication that printed the actual wording of anything like the contents of the historical testimony recorded in the MCGC during the 1624 trial, through the U.S. Postal Service, a criminal offense.22 The MCGC serial in the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography was probably mailed to subscribers. So, in fact, since the Comstock Act was at that time law, the historical witness testimonies in Cornishe’s trial was, to quote McIlwaine’s explanation of the omissions, literally “unprintable” and “not fit for publication”.

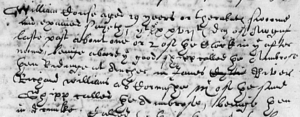

Original record, first censored by McIlwaine in 1913. Library of Congress Image 75, Minutes of Council and General Court.

McIlwaine’s 1924 transcription of original content above, pg 34, MCGC, VA State Library,1924.

Interestingly, eleven years after, though Comstock was still law, McIlwaine did wind up publishing the complete transcriptions of the two historical Jamestown Cornishe trial testimonies from 1624, in his second publication of the MCGC transcription. Why did a second printing of the MCGC even occur? In his own words, in the preface, McIlwaine explains, “The great mass of the records of the General Court of Virginia, both for the colonial period and a later period, was destroyed in the burning of the State court building …on the night of April 2, 1865, when Richmond was evacuated by the troops of the Southern Confederacy.”23 How then did the MCGC survive a fire? It was fortunately not in the court house on April 2, 1865. The MCGC was borrowed from the early Virginia Council (well after 1624, probably during the colony’s first one hundred years) to inform a history book the borrower intended to write. The researcher promised to return the records but fortunately never did. He passed on with the MCGC still located in his personal library. Upon his death, Jefferson purchased the by then forgotten but rediscovered records from the deceased researcher’s grandson in 1778.24 McIlwaine and the publishers of the second version, the Board of the Virginia State Library, learned the invaluable lesson from the record’s own history of just how vulnerable and precious its contents were. In its Preface McIlwaine wrote, “It only remains for the State through its proper agencies and for the historical workers of the State to gather up with pious care the fragments that are left from this reservoir and other reservoirs of Virginia’s history, place them in fireproof repositories, and, further, by publication insure them – that is, their content and spirit – not only from loss by fire but from all forms of deterioration gaining for them, at the same time, in this way wide dissemination and availability.”25 Demonstrating his and the Board’s priority in protecting the complete historical record for posterity, perhaps at the expense of legal ramifications, McIlwaine wrote, too, of the MCGC, “There is no question, however, that they are of such superlative value to the student of early Virginia history as to justify their being printed again, in a volume made up almost exclusively of Court and Council minutes and notes made from these, in which, by the aid of a full index, they may be conveniently studied.”26 So, “…the State Library Board had… determined to have printed in one volume all the minutes of the proceedings of the Council and General court that could be found…”27 The book was a limited printing of 500 copies which may seem small, today, but at the time it was probably an appropriate release for the number of intended users: “…the student of early Virginia history…”. It is unclear if any were mailed and there is no record that either McIlwaine or any Board members were ever charged with any crime.

The Richard Cornish Endowment Fund – Created By College of William & Mary GALA LGBTQ Alumni Association.

Unsurprisingly, it turns out that these two redacted historical testimonies eventually being brought to light was very important and not just to my work. Since being revealed, the history of Cornishe’s trial has, at least in America, led to Richard Cornish being today considered a folk hero particularly to the LGBTQ community because he is remembered as the first known person arrested a criminal and executed for having committed sodomy28 Too, that the sentence of execution Cornish received was perceived as just (moral), was not unlike the intent behind the Comstock Act: a law since ruled “an unconstitutional restriction on free speech”29 or unjust, but nonetheless enacted on the same continent Cornishe was executed, 250 years after his death.

Thanks to Thomas Jefferson, upon its creation, the original MCGC was among the first founding documents archived in the Library of Congress where it continues to be held today.

For my work McIlwaine’s omissions offered a way to begin. If I could not read historical trial testimony because it had been considered illicit all I could learn was the record’s context. Knowing of the existence of the testimony or not, if I was to write about him, I had to understand as much as possible about the places Cornishe went, the work of a mariner Master, and as much as possible about the time period. The MCGC in all of its forms has been invaluable helping me to do that. So the historical record when omitted and when printed in full remains crucial to the advances in my work. The omission challenged me to see if I could learn anything at all about Cornishe and once I began to, the full transcriptions of the trial testimony finally revealed the recorded testimonies.

© 2019 Arlene Spencer. All Rights Reserved.

- McIlwaine, HR, ed. 1924. Minutes of the Council and General Court of Colonial Virginia. Richmond: Virginia State Library, v.

- Spencer, Arlene. 2019. “New Evidence: Was Thomas Weston, Seventeenth Century London Merchant among the First to Sail Fish to Virginia’s Starving Colonists?” Global Maritime History. as of April 4, 2019.

- McIlwaine, HR, ed. 1913. “Minutes of the Council and General Court 1622-1629.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 21 (1):61.

- McIlwaine, HR, ed. 1913. “Minutes of the Council and General Court 1622-1629.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 21 (2):144.

- McIlwaine 1924, 34

- McIlwaine Apr 1913, 34

- https://www.loc.gov/collections/thomas-jefferson-papers/articles-and-essays/virginia-records-1606-to-1737/ as of April 2, 2019.

- McIlwaine 1924, xi

- Swindler, William F. 1980. Book Review of Legislative Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia and Minutes of the Council and General Court of Colonial Virginia.” William and Mary Law Review 22 (2): 321-326.

- Swindler 1980, 325

- McIlwaine 1924, xi

- Crompton, Louis. 1976. “Homosexuals and the Death Penalty in Colonial America.” Journal of Homosexuality 1 (3):292-293.

- Clemmons, Harry. 1957. “Some Jefferson Manuscript Memoranda of Colonial Virginia Records.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 65 (2):154-168.

- McIlwaine, H.R. 1911. “Minutes of the Council and General Court, 1622-24.” “Prefatory Note.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 19 (2):113.

- McIlwaine 1924, 93

- Crompton 1976, 290

- Wolfe, Brendan. 2012. “Spotlight: Richard Cornish. Encyclopedia Virginia Project Blog. https://www.evblog.virginiahumanities.org/2012/06/spotlight-richard-cornish/ as of April 2, 2019

- McIlwaine 1924, 93

- Rictor Norton (Ed.), “The Trial of Richard Cornish, 1624”, Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England: A Sourcebook. Updated 15 June 2008 http://www.rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/cornish.htm.

- McIlwaine, Jan. 1913

- McIlwaine, Apr. 1913

- U.S. Obscenity Law on Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_obscenity_law as of April 18, 2019

- McIlwaine 1924, v

- McIlwaine 1924, viii

- McIlwaine 1924, v

- McIlwaine 1924, viii

- McIlwaine 1924, ix

- Goodheart, Adam. The Ghosts of Jamestown. The New York Times. July 3, 2003. https://www.nytimes.com/2003/07/03/opinion/the-ghosts-of-jamestown.html as of April 15, 2019

- Wikipedia Obscenity Laws 2019 as of April 18, 2019

Very well written! Thank you for your hard work in researching and providing such a thorough article on your findings. Very impressive indeed!