While mulling over what I should write about in this, my first blog on our new website, I thought I should pay tribute to naval historians past and present, then I thought to discuss the navy itself as a general concept – the Royal Navy of the United Kingdom and all navies of all countries in all periods, the very stuff which this website is designed to research and present. That lead me to think about what navies have done for their countries, especially of course what the Royal Navy has done and is doing for my country. It was inevitable that this train of thought should lead to a question many people have addressed in recent years and which has exercised my mind and my passions in journal articles, conference speeches, lectures to students and private conversations. Just why do we need a navy?

While mulling over what I should write about in this, my first blog on our new website, I thought I should pay tribute to naval historians past and present, then I thought to discuss the navy itself as a general concept – the Royal Navy of the United Kingdom and all navies of all countries in all periods, the very stuff which this website is designed to research and present. That lead me to think about what navies have done for their countries, especially of course what the Royal Navy has done and is doing for my country. It was inevitable that this train of thought should lead to a question many people have addressed in recent years and which has exercised my mind and my passions in journal articles, conference speeches, lectures to students and private conversations. Just why do we need a navy?

Navies are expensive, highly technical and by their nature as armed services, questionable in a world largely at peace. In the past navies were vital to the very existence of states, more so to England perhaps than any country. The largest state on a large island stuck out into two oceans on the edge of a great continent, England naturally looked to the sea as an efficient means of communication with our neighbours in the British Isles and with our European neighbours across the North Sea and the Channel. The sea was – and remains – the source of good food both offshore and inshore, and was the workplace of fishermen for generations. It was the route whereby the wealth of other nations could be imported – spices, sugar, chocolate, tea and coffee, silks and raw cotton. It was the route for the export of our goods, especially wool and corn, and in later years of a vast array of products made in the first great industrial factories. It became the route by which our culture, our politics, our religion, our moral code and of course our language was spread throughout the world, for good or ill.

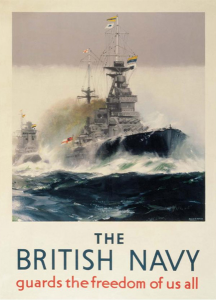

Protected by the growing strength and efficiency of the Royal Navy in the Seventeenth century, English – and then British – trade grew in size and extent, reaching across the narrow seas and the great oceans almost with impunity. Surely that was the purpose of the navy, expensive to run, difficult to manage but vital to the country’s prosperity in its protection of the merchant mariners’ rights to the freedom of the seas.

But the ease with which we could make contact peacefully with our neighbours and even distant lands carried with it a hidden threat. The danger of invasion by other states who wished to own us or to subdue our rising power and wealth.

At the time this thought coalesced I was drafting a talk to be given at a conference at the National Maritime Museum in the summer of 2013. My talk was about the manner in which naval officers delivered the nation’s political strategy, especially in safeguarding the freedom of the seas for peaceful commerce. In my research I re-read a chapter in a volume of the Oxford History of the British Empire which made me rethink my thesis – that the main purpose of a navy was to safeguard the nation’s wealth generated by maritime trade.(1)

In N A M Rodger’s chapter he dismissed this idea and – as so often with his work – cogently put forward a different argument well supported by evidence, the argument that ‘the [British] navy’s primary function was to guard against invasion’. Cogently, but for me not totally convincingly. Even after thinking about Dr Rodger’s essay carefully, referring to many of his sources and giving time to consider his argument, I still subscribe to the idea – which he describes as the ‘approach traditional among naval historians’ – that the function of a navy is to protect a nation’s right to trade. On our maritime planet, especially for an island nation with global connections, that means protecting the freedom of the seas. I will discuss this in more detail in an article I will publish on the BNH website soon, and hope that it will ignite a debate amongst our community about the purpose of navies in the modern world.

And so with that in mind I thought I should write my first blog for our new website about the importance of navies, to my country and to others, starting hares running and inviting discussion, as blogs should. It starts with a brief look at the development of navies in a global context.

The naval history of Asian and south-east Asian states is not well known to western history studies partly because of the Eurocentricity of university courses. However, there are useful lessons to be learned from a brief examination of the naval history of China and Japan, although these states did not have the political will or strategic need to expand beyond their immediate maritime boundaries that drove the maritime exploration and related naval projection of the European states. (2)

In Ming dynasty China, rulers encountered criticism at home for wasting money on building ocean-going junks, and within a few years of their explorations westwards they withdrew their navies and embargoed international trading for all but essential goods, turning their political and military attention inwards. Their early technological superiority at sea did not come into conflict with western navies until much later in the evolution of European naval capability. It was not until the 1660s, when China invaded Taiwan to expel Dutch and Spanish traders that such encounters began to happen in earnest, when the better sea-handling characteristics of Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and, much later, English square-rigged, deep-draught and keeled vessels and the superior firepower enabled by corned gunpowder and broadside-firing tactics gave western ships the edge. The response of the Asian states to growing western maritime power was to ignore it due to a different set of priorities. It is this set of priorities which is at the heart of the question of sea-power today.

This inward-looking orientation of the largest Asian states formed Halford J. Mackinder’s hypothesis of the differing priorities held by continental (‘Heartland’) states and by maritime (‘Rimland’) states, inhibiting major clashes between them until the Nineteenth century when long-range land transport became practical, later followed by the military possibilities of long-range, large-scale air transport enabling blitzkrieg invasion. At the time he propounded his theory, Mackinder thought the evolution of land transport would allow the Asiatic continental states to rise, and that sea-power was redundant.

However, we are an oceanic planet and the bulk of trade goods continues to flow by sea. Continental powers depend as much on the sea for economic prosperity as do maritime states and this dependence grows as their industrial economies expand and their extra-mural supplies and markets with it. Mackinder’s hypothesis collided with Alfred Thayer Mahan’s view that global power demanded maritime reach.

In the modern world we have seen the reality that even great continental powers cannot turn their back on the sea. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was financed by sea-trade and built a modern navy; Germany with its short coastline built a large merchant fleet trading across the globe and a navy intended to force a world-wide empire to compete with Great Britain; Czarist Russia, a relatively minor naval power in the age of sail, developed a powerful navy once steam-power enabled large-ship movement in their difficult, often confined waters, and the immense fishing, whaling and merchant fleets of the USSR were backed by an impressive navy which wielded strategic might; the United States, essentially a continental power, virtually created its mercantile export trade on the back of a rapidly enlarged blue-water navy after the Civil War; and China, a sleeping tiger for 500 years, is now becoming the world’s merchant carrier – it is no coincidence that the powerhouse of Chinese trade and the most potent symbols of its burgeoning prosperity lie along its coastline. Mackinder’s Rimland states – the traditional maritime nations – are thus at risk of losing their pre-eminence in maritime trade.

Maritime trade still matters greatly to the modern global economy and thus we see that China, the rapidly emerging economic power, is developing a coherent maritime geo-policy for the first time in half a millennium; it is expanding its blue-water navy which several naval historians predict will become paramount in the 21st century, to the concern of all nations around the Pacific rim and beyond.

Considering all this it seems redundant to ask ‘What is a navy for?’ This central issue, a concern exercising all states since armed ships first entered the sea, was dealt with robustly by Professor Geoffrey Till of King’s College London in a guest article in the US Naval War College Review (Winter 2009), in which he stated that the primary concern of an armed maritime force is to protect trade; his secondary purposes include fighting wars, especially mounting what he terms ‘distant expeditions’, and preventing or deterring third-party conflict at sea.

It seems to me that naval power fulfils many other legitimate concerns of a modern democratic state, such as:

deterring attack, both strategic (e.g. with submarine-borne missiles poised against unilateral nuclear attack – a proven deterrent if now fashionably unpopular), and tactical (defence or deterrence against terrorist attack on coastal assets such as oil rigs or mercantile seaports);

policing actions against piracy, people trafficking, illicit drugs trafficking, customs evasion and oceanic environmental pollution;

and a nation which prides itself as a civilised society with compassion for others in need, would also want to use its navy to provide quick response specialist skills and heavy-lift assistance to victims of natural disasters, both for maritime littoral communities and as ship-borne airlift support for the victims of inland disasters.

All this demands financial resourcing. Being highly-technical and requiring large-scale industrial and technological input and skilled specialist personnel, navies are expensive, as the Ming dynasty found. If the need to maintain a naval presence is important, defending a nation’s assets and maintaining the free global passage of economically vital trade, it will also cost money. Navies have to be designed and trained to fight – in ship-to-ship or ship-to-air actions at sea, as amphibious launch and relief in littoral attack, as power-projection ashore, as logistical heavy-lift support for land war, and for over-the-horizon carrier-borne air support – but ultimately their purpose is the protection of a state’s way of life against external threat. For maritime states on an oceanic planet, armies and air forces cannot do that.

States have to make choices about the kind of society they wish to be and how to resource them, and in tight economic times those choices become ever more difficult. However, Britain does not have a choice. We are not a continental nation, although allied financially, commercially, and increasingly politically and militarily with our continental neighbours. We are gens-de-mer, a maritime nation on an oceanic planet, with experience and expertise in sea-going trade, if not now an inherently maritime culture.

The United Kingdom still has a world-class presence in the maritime economy, both in goods and in services, and still has a high-level naval capability, and we should maintain that disparate set of expertise to leverage our advantages if we are to compete and maintain our level of prosperity.

If we are not big players in the global maritime world we will give away major opportunities to earn foreign income, to carry the world’s goods, to service the world’s shipping, to safeguard our own exports, to protect our coastal strategic assets such as ports, oil rigs and wind farms, and to project vital assistance anywhere in the world when natural disasters strike. We need a strong naval presence, not to wave the White Ensign in the face of Johnny Foreigner, but to protect our trade and our people and those of our continental neighbours going about their lawful business on the high seas.

Now, if that sounds old-fashioned and Blimpish, let us remind ourselves that human nature has not changed just because we are better fed, better housed and have more freedom than our ancestors could have dreamt of. We have enemies out there who would deprive us of that freedom, our hard-won right to think and to speak as we wish. Powerful men, who suborn their poverty-stricken compatriots to steal our hard-earned wealth. Clever men who know better but cynically lie and dangle fantasies in front of our children to fill their minds with religious hatred and urge them to suicide and murder.

Our sea-lanes are increasingly at risk at a time when our naval capabilities are under threat. Navies are not just about strategies and tactics, weapons, logistics and ship design. They are, above all, about the men and women who serve in them. We need a Navy for the future, and must invest in our people to create our naval future.

References in the text:

1) NAM Rodger, ‘Sea-Power and Empire, 1688-1793’, in Oxford History of the British Empire, volume II: The Eighteenth Century (Oxford 1998), pp169-182; online at Oxford Scholarship Online DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/978019822056630.003.0008, last accessed 26 July 2013

2) My interest in the navies of early modern China and Japan was stirred by my former doctoral supervisor, Professor Jeremy Black, who discussed this with great perception in the inaugural Alan Villiers Memorial Lecture at Oxford, in September 2010

© J M J Reay September 2013