The city’s namesake was the first person ever to survey or chart the Pacific Northwest. British Commander George Vancouver produced some of the most accurate and detailed maps of the region ever, even by today’s standards. So, it is appropriate that the Vancouver Maritime Museum (VMM) located at 1905 Ogden Avenue in the Kitsilano neighborhood of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; provides more than an informative and pleasant museum tour at a scenic beach. It also houses a repository of varied historical archives available to the public, for the simply curious or for scholarly research. Aside from some exhibits in the University of British Columbia’s Museum of Anthropology, the VMM is the only maritime museum in Vancouver.

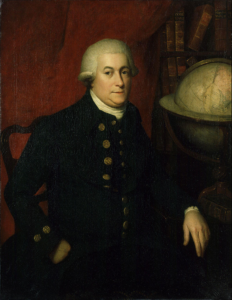

Late 18th c. Believed to be George Vancouver from the National Portrait Gallery London. Artist Unknown. Source Wikipedia

Captain George Vancouver’s “charts of the North American northwest coast were so extremely accurate that they served as the key reference for coastal navigation for generations. Robin Fisher, the academic Vice-President of Mount Royal University in Calgary and author of two books on Vancouver, states: “He put the northwest coast on the map…He drew up a map of the north-west coast that was accurate to the 9th degree, to the point it was still being used into the modern day as a navigational aid. That’s unusual for a map from that early a time.””1

Commanding the HMS Discovery and the HMS Chatham on April 1, 1791, Vancouver departed England to fulfill his commission to explore the Pacific Northwest for the British Kingdom. The Vancouver Expedition came to be because in 1789 “the Nootka Crisis developed, and Spain and Britain came close to war over ownership of the Nootka Sound on …Vancouver Island, and of greater importance, the right to colonise and settle the Pacific Northwest coast. …When the first Nootka Convention ended the crisis in 1790, Vancouver was given command of Discovery to take possession of Nootka Sound and to survey the coasts” (Wikipedia, George Vancouver).

Map of Vancouver British Columbia Canada. Source Lonely Planet

In the middle of June 1792 Vancouver was the second European to enter Burrard Inlet or the present day harbor of the City of Vancouver. The commission was granted, too, so that finally, after 400 years of searching, it would be determined whether a Northwest Passage, a direct waterway between England and the Orient, existed across the North American continent. If it did, it would be a great advantage to British trade. In the end Royal British Navy Commander George Vancouver returned home to England and reported that no, the Northwest Passage did not exist.

But had Vancouver been wrong? Was the Northwest Passage, in 1792, still to be discovered?

One of Vancouver’s original charts of the North American Pacific coastline, including most of the coasts of the Canadian province of British Columbia, and portions of America’s Oregon and Washington State coastlines, hangs prominently in the Vancouver Maritime Museum’s Navigation Gallery.

Also on display in the Navigation Gallery, is “The Arnold 176 chronometer, probably the Vancouver Maritime Museum’s greatest treasure, …used by Captain George Vancouver during his five-year voyage of exploration in the Pacific from 1791 to 1795, which resulted in the charting of the Northwest Coast from California to Alaska.

“The Arnold 176 was made by John Arnold in London, likely prior to 1787. Arnold numbered all of his time pieces, hence the name “Arnold 176.” Chronometers were exceptionally accurate timepieces, used at sea to help navigators plot longitude. A slow or fast running chronometer would throw off the navigator’s calculations, and could lead to shipwreck. Most ships carried four to five chronometers to check against each other.”2

Opened in 1959, the Vancouver Maritime Museum displays artifacts and educational material in sixteen different galleries, two of which are specifically designed for children, though all of the galleries include information suited to visitors of any age, including rotating exhibits some of which tour the nation. The Heritage Harbour is an outdoors exhibit just meters from the museum and features 12 historical vessels which visitors are welcome to climb aboard and tour.

The two featured exhibits currently on display are: Making Waves Exhibit, on view through winter 2020, depicting the origins of the Greenpeace organization and this Vancouver nonprofit’s first voyage in 1971 to Alaska to protest nuclear testing and its subsequent work fighting to end international whaling. The other currently featured exhibit is Celebrating the St. Roch, in which the actual restored vessel is on view until August 2019.3

May 7, 1928 the RCMP St. Roch was launched directly across the water from Vancouver, for her maiden voyage, from Burrard Dry Dock in North Vancouver on Burrard Inlet.4

In the 1930’s and 40’s some of the first and only patrols in the Arctic Ocean and later the Northwest Passages were commanded “…by Henry Larsen, a Norwegian Canadian, in a small wooden Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) schooner, St Roch, especially built as a floating police detachment, and with a crew of 7 and 10.”5 St. Roch was among the first Royal Canadian Mounted Police vessels to enforce the law where today Canadian and American ice breakers and American nuclear submarines monitor the seas (Reidel 2015). Not nearly as powerful as an ice breaker or a submarine, nor configured much differently today than her original 1928 design, the St. Roch “is 31.6 metres long with a beam of 7.6 metres, a depth of hold of 3.4 metres and a displacement of 323 tons. St. Roch is made primarily of thick Douglas fir planks with hard Australian Eucalyptus ‘iron bark’ on the outside and an interior hull reinforced with heavy beams to withstand ice pressure.”6

The vessel transported supplies, assisted vessels and small outpost communities, monitored and noted weather, and natural features for the Canadian government, and maintained one of very few floating detachments of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police existing at all at that time in the Canadian territories and waterways north of British Columbia (Riedel 2015).

Strangely, in 1940, this small police schooner, was unexpectedly and suddenly sent to attempt to navigate the Northwest Passage, to cross the Arctic Ocean: the second vessel ever to do so since “…Roald Amundsen, made the first documented, successful transit of the sea route above the North American continent in 1905-06” (Riedel 2015).

“For almost half a century, the reasons behind orders sending the RCMP schooner St. Roch through the Northwest Passage during the Second World War have puzzled historians and other scholars. True, there were rumors of a defence-related mission, but there was no hard evidence, no tangible proof. Nor did the captain, Sgt. Henry Larsen, provide many clues other than “Canada was at war and the government had realized the need to demonstrate the country’s sovereignty over the Arctic islands” … a statement not verified in official documents. Then unexpectedly last year, during research on Canadian wartime relations with Greenland, two memos were found in RCMP archival files that directly linked the voyage of the St. Roch to a government plan to defend and occupy the island in the spring of 1940 ….”7

In April 1940 Denmark had fallen to the Nazis and the British and Canadian governments feared Greenland, a Danish colony rich in valuable minerals and many natural harbors, could become useful to, or worse, fall to Hitler. Reports indicated Nazi submarines and other vessels were heading for Greenland. “Considering that in 1940 Canada had no arctic airstrips and no RCN vessels available for polar navigation, the RCMP schooner was a logical support ship and patrol vessel”(Grant 1993). From 1940 through 1942 and then once more in 1944 the St. Roch crossed and returned from the Northwest Passage to occupy Greenland (Grant 1993). Though the St. Roch never landed at Greenland its heroism as a small vessel that was frequently ice locked, only outfitted with a radio with a range of only 200 miles, operated by a small crew who lived in unusually tight quarters with nearly no modern amenities working in service to the Allies’ war effort, their sailing against Nazi vessels placed the ship and crew in national and world history (Riedel 2015).

By the late 1990’s it was recognized that something was need to be done if the St. Roch was to be maintained, as she was “in desperate need of restoration and long term preservation.”8 So, in the late 1990’s The “…RCMP catamaran Nadon was christened St. Roch II and set out from Vancouver to retrace the 1940-42 voyage of the St. Roch as a promotion to help raise funds. Money generated from sponsors of the voyage and the publicity of the campaign would be used to preserve the aging St. Roch” (Northwest Passage Hall of Fame St. Roch II). They succeeded and fully restored and preserved the St. Roch on display, today, in the Across The Top Of The World exhibit. A fascinating film featuring actual footage shot by St. Roch‘s crew including Inuit people, arctic mammals and wildlife, seal hunting, sailing in ice floes, and other extraordinary experiences is available for visitor viewing at least once an hour next to the St. Roch at the Museum’s Across The Top exhibit (Vancouver Maritime Museum Map 2019).

St. Roch, Vancouver Maritime Museum

Upon the Museum’s launch “…when the building first opened its doors in June 1959, things were very different. The official dedication (which took place on June 11) was attended by more than 500 people, including RCMP Supt. Henry Larsen, who had spent nearly 20 years on board the St. Roch. Unfortunately, other than the boat, the museum had almost nothing else to share with its guests. The building stayed open for only four days before shutting its doors again for almost a year.”9

But today, besides providing public viewing galleries of artifacts and educational exhibits The Vancouver Maritime Museum maintains and makes available to the public its: W.B. and M.H. Chung Library, an artifacts collection, and the Leonard G. McCann Archives.

“The Library provides public access to information about maritime history, art, culture and technology. The Library holds over 12,000 books and published manuscripts dating 1678-2014; and 510 bound and unbound periodicals. …The primary focus of the collection is the maritime exploration and history of the Pacific Northwest, specifically Vancouver and coastal British Columbia. Other subjects include early Arctic and Antarctic exploration, Canadian naval history, naval architecture and the science of navigation. Alongside the standard scholarly monographs, the Library has collected other types of publications and records including registers of shipping, the record of seamen shipped at the Port of Vancouver and ship’s logs” (Vancouver Maritime Museum https://www.vancouvermaritimemuseum.com/education/library). The Library also retains some of Captain Cook’s original hand drawn charts from his exploration of the Pacific.10

“As the primary local repository for maritime history, the Vancouver Maritime Museum houses over 15,000 objects and 100,000 images either in storage or on exhibit. Our holdings reflect the city’s long connection with Vancouver, the Pacific Northwest and the Arctic, and the collection represents European, Asian, North American and First Nations sources. Objects include navigational tools, books, charts, posters, and uniforms that touch on naval history, the Vancouver waterfront, shipping, recreational watercraft, and marine harvesting. We strive to represent these communities and their connections to the sea, through the acquisition of cultural and scientific objects relating to countries on the Pacific and the Arctic Oceans” (Vancouver Maritime Museum https://www.vancouvermaritimemuseum.com/permanent-exhibit/our-collection).

“To date, the archival collection includes 60.0 meters of processed fonds and collections related to vessels, shipping companies and maritime personalities” (Vancouver Maritime Museum https://www.vancouvermaritimemuseum.com/education/archives).

The Vancouver Maritime Museum’s artifacts collection and the Leonard G. McCann Archives’ holdings and information about historical vessels can be found by querying the Museum’s Open Collection’s online catalog at https://vmmcollections.com/.

The W.B. and M.H. Chung Library is searchable online through the Chung Library Catalogue at https://chunglibrary.libib.com/.

The Museum’s St. Roch archive has its own finding aid online at https://stroch.net/.

Visitors are welcome to the Library by appointment only and for those not planning to visit the Vancouver region, the Library offers research and copying services. To arrange a library appointment or review the library’s copying fee schedule see https://www.vancouvermaritimemuseum.com/education/library.

Archival finding aids are also available on the Museum’s site at https://www.vancouvermaritimemuseum.com/education/archives.

Three and a half years later, when he sailed into England in September 1795, Vancouver had finally returned home. Though he confirmed for the crown that no, a Northwest Passage did not exist, and even though his charts of the Pacific Northwest coast were incredibly accurate, Vancouver did not include on any of his maps the largest waterways on the Northwest Pacific coast: the Skeena River in northern British Columbia; the Fraser River, the longest river in British Columbia comprising much of the province’s eastern drainage; nor the Columbia River: the natural boundary between Washington State and Oregon, the fourth largest river in the United States by volume, and the largest river in the Pacific Northwest. He evidently never saw any of these major waterways, any one of which could have turned out to be the invaluable Northwest Passage (Wikipedia George Vancouver). Yet, in spite of this, Vancouver was correct. No Northwest Passage existed.

“”Vancouver is the largest port city in Canada,” [sic. VMM Executive Director Joost Schokkenbroek] explains, “larger than the five smaller ones combined. It’s the third-largest in North America. The city of Vancouver deserves a major maritime museum telling that story. Talking about how it developed. Talking about First Nations. The land and the sea. It’s a gripping story to tell””(Donaldson 2019).

Indicating that the VMM is indeed telling that story, the City of Vancouver Archives lists first the VMM’s “Maritime Museum Collection” on their Vancouver maritime history reference guide.11

The Vancouver Maritime Museum’s hours of operation and other information may be found at https://www.vancouvermaritimemuseum.com/

Burrard Inlet, Vancouver, British Columbia

© 2019 Arlene Spencer. All Rights Reserved.

- Wikipedia. George Vancouver. Navigation. Accessed July 3, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Vancouver.

- Vancouver Maritime Museum. Featured Exhibits. Arnold No. 176 Chronometer (Built Circa 1780). Accessed July 3, 2019. https://www.vancouvermaritimemuseum.com/permanent-exhibit/featured-exhibits.

- Vancouver Maritime Museum Gallery Map. 2019 Highlights. Vancouver Maritime Museum. June 2019.

- Twitter. Maritime Museum. @vanmaritime. 2pm, 7 May 2018. Accessed July 3, 2019. https://twitter.com/vanmaritime/status/993596553293053952.

- Riedel, Doreen Larsen. The Most Northerly Route – Looking Back 70 Years. Royal Canadian Mounted Police Scarlet and Gold Veteran’s Association Vancouver Division. January 27, 2015. Accessed July 3, 2019. http://www.rcmpveteransvancouver.com/the-more-northerly-route-looking-back-70-years/.

- St. Roch National Historic Site of Canada. Canada’s Historic Places. Accessed July 3, 2019. https://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=9159.

- Grant, Shelagh D. 1993. “Why The St. Roch? Why The Northwest Passage? Why 1940? New Answers To Old Questions.” Arctic Profiles 6 (1):82-87. The Arctic Institute of North America.

- Northwest Passage Hall of Fame. St. Roch II: Voyage of Rediscovery. Accessed July 3, 2019. http://www.nwphalloffame.org/history/st-roch-ii/.

- Donaldson, Jesse. 2019. “After 60 Years, Vancouver Maritime Museum Sets Sail for the Future.” The Tyee. 3 June 2019. https://thetyee.ca/Presents/2019/06/03/Vancouver-Maritime-Museum-Sets-Sail/

- Vancouver Maritime Museum. Wikipedia. Accessed July 3, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vancouver_Maritime_Museum

- Maritime History Reference Guide. City of Vancouver Archives. Accessed July 3, 2019. https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/archives-reference-guide-maritime-history.pdf

Pingback: Canadian History Roundup – Week of July 14, 2019 | Unwritten Histories