Brenna Gibson of the University of Southampton discusses late-medieval Suffolk seafarers. Please click on the figures to view them, they will appear larger in a new browser tab.

Of nyce conscience took he no keep.

If that he faught, and hadde the hyer hond,

By water he sente hem hoom to every lond.

But of his craft to rekene wel his tydes,

His stremes and his daungers him bisydes,

His herberwe and his mone, his lodemenage,

Ther nas noon swich from Hulle to Cartage.

Hardy he was, and wys to undertake;

With many a tempest hadde his berd been shake.i

Geoffrey Chaucer, ‘ The General Prologue ’ , in The Canterbury Tales

Intro/Context

As an island nation, seafarers during the fourteenth century formed the backbone of England. Without the complex trade networks that English seafarers created, England would have been completely cut off from any influence, goods and culture the Continent offered. Closer to home, they not only fished the seas both inshore and offshore, but they also were an integral part of the country ’ s martial and diplomatic endeavours through the transport of armies, supplies and envoys. It is because of the numerous wars seen throughout the fourteenth century that we have records of mariners today.

The fourteenth century saw the reigns of Edward I, Edward II beginning in 1307 and Edward III beginning in 1327, as well as Richard II in 1377. These reigns witnessed a wide array of domestic and international challenges, with each monarch succeeding and failing at different times. Edward II inherited the throne in 1307 at age fourteen, after the death of his father, Edward I, and with it an ongoing war with Scotland. He quickly withdrew from this war, much to his barons ’ annoyance.ii Clashes with his barons led to domestic turmoil, which the Scottish took advantage of by weakening the English hold in Scotland and even raiding in Northern England. Eventually, Robert Bruce pushed the English completely out of Scotland during the Battle of Bannockburn on the 24 th of June 1314, which led to a truce that lasted until 1323.iii On top of this defeat, years of harsh weather and bad harvests created a deflated market and caused widespread famine (and consequently, deaths) in 1315.iv Power fluctuation between Edward and his opposition caused distrust between the king and his subjects, so much so that Edward had very few supporters when his wife, Queen Isabella of France, invaded England in 1326. This conflict continued until Edward ’ s death in 1327, the cause of which is highly debated.v

The reign of Edward III is seen as the most unified of the fourteenth century, particularly in comparison to Edward II. While initially under his mother ’ s influence when he took the throne, Edward put an end to her attempts at power by 1330 and initiated rebuilding the domestic-state of his kingdom. Sir Thomas Gray describes the ideal way to keep power and maintain peace with his lords and society as a whole, and it is certainly a view that Edward III, more so than Edward II, had as well:

It is always said that running water is the strongest thing that can be, for although it is gentle and soft by nature, because all of the particles of water take their part pushing equally in the flow, therefore it pierces hard stone. It is just so with a nation that with one mind, turns its hand to maintaining the estate of its lords, who do not desire anything save the good of the community, nor individually strive for any other aim. Amongst such a people an upheaval of society is seen very rarely, at least regarding changes in the estate of their lords, which is the greatest dishonour to the people.vi

While his motivations were numerous, Edward III gave his people a single vision by declaring himself king of France and starting the Hundred Years War. With important victories at the beginning of the Hundred Years War, as well as his creation of the Order of the Garter, Edward III and his reign are remembered in a more positive light than his father. However, it is during this time that the English population was once again struck down by disease; in 1348, 1360 and 1373, England was hit with the Black Plague, which devastated the population numbers even more than the famine in 1315. Port towns, perhaps more so than any other types of English towns, were most at risk from the Plague since England, as an island nation, would have had to ‘ import ’ the disease from other countries. In fact, these cities were in ‘ constant, almost daily contact with the continent or with the Channel Islands ’ .vii While records tend to contradict one another, it is believed that the original strain of the Plague came into England through Melcombe, Bristol or Southampton, and was transported home on ships returning from the siege of Calais.viii

Suffolk Ports in the Fourteenth Century

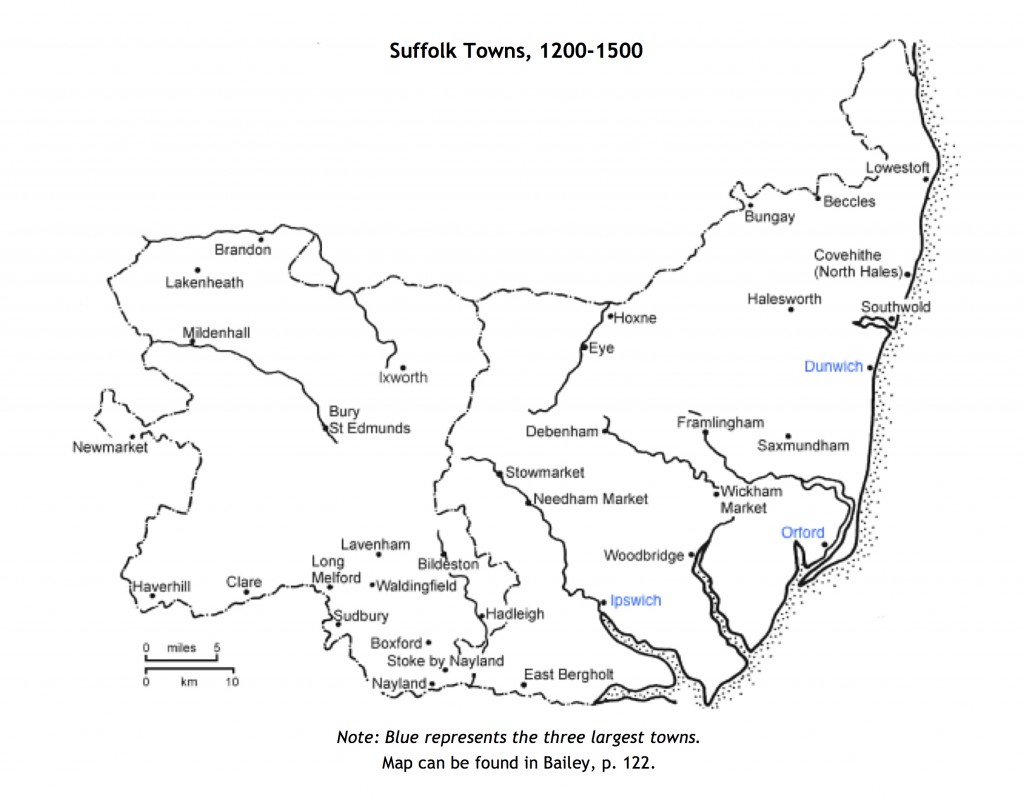

Suffolk, much like the rest of England in the fourteenth century, was primarily agrarian in nature, even in the larger port towns of Ipswich, Orford and Dunwich.ix However, the added aspect of maritime trade (bolstered by its safe, large harbour) helped make Ipswich the largest town in Suffolk.

As can be seen in Table 1, Ipswich sits comfortably as the largest town in Suffolk in 1327, with the margin between itself and the next largest towns (Beccles and Bury St Edmunds, respectively) growing from 1327 to 1332. In fact, by 1332, the port towns on this list make up over half the taxable wealth.

Ipswich, Dunwich and Orford were each centres of a wide variety of trade, including wool and grain. However, each port had its own significance. With many specialist tanners residing in the city, Ipswich was the centre of the leather trade, with its main trade overseas consisting of ‘ wine, ale, herrings, hides, linen and canvas cloth, wool, millstones and salt ’ . In addition to acting as the largest town and port in Suffolk, Ipswich also served as the ‘ centre of the county ’ s administration and system of justice ’ .x Dunwich and Beccles exist only because of the herring trade for which they was established. Orford was a military stronghold. The smaller port towns of Orwell and Gosford on the Deben Estuary, both of which no longer exist today, relied heavily on the imports of German and French wine.xi

Source Material

Despite the fact that documents surviving from the fourteenth century are often incomplete or damaged, because of the high number of wars during this century a huge number of records still exist. Seafarers appear in Exchequer accounts, the Chancery and the Patent Rolls, among other records. From these records, three key pieces of information can be taken: the name of the owner or master of the ship, the name of the ship and the port from which the ship sailed. It is these pieces of information that I am most interested in, as opposed to the amount paid or what was being transported.

Fourteenth-century records lack statistical information, causing economic historians to struggle to speak with certainty on this period. It is here that the lay subsides and poll taxes can be beneficial, if used cautiously. There were two main tax levies in the fourteenth century: the Lay Subsidy in the first half of the century and the Poll Tax in the later half. During the fourteenth century, the most comprehensive lay subsidies are from 1327, 1332 and 1334. The next sets of taxes with a high amount of surviving records are the Poll Taxes of 1377, 1379 and 1381. The 1377 Poll Tax provided the most comprehensive demographic information, with the information given in 1379 and 1381 proving best for socio-economic studies. All three offer valuable information not only about the amount a person was taxed, but also about their occupation. An important change seen in the Poll Taxes was a sliding scale of taxation, rather than an individual being taxed based on moveable wealth.

The methodology for the gathering of my data is relatively straightforward. Using the records of the Chancery, Exchequer and other material, a database has been compiled that contains prosopographical data on seafarers ’ careers. This database has over 8,000 records relevant to the fourteenth century.xii This information includes the names of their ships and the ports from which they sailed, in addition to the nature, the geographical range, and the dates of their voyages. Often the size of the crews is also recorded, therefore providing valuable demographic data. From here, a comparison is made between the names of shipmasters for whom their ships’ home ports are specified in the naval records with the names of taxpayers listed for those same ports. Due to the problems associated with nominal record linkage, we can never be certain of linking royal governmental records. However, if done carefully, important work can be done on this occupational group.xiii Consequently, certain parameters were created in order to ensure a reliable dataset: each match must have an unusual name, have sailed within 20 years of the tax year, and have been found within a ten mile radius of the port city. In other words, a ‘John Smith’ who is listed from outside the radius is not considered a match. However, John Irp, for example sailed from Ipswich in 1325; he appears in the 1327 Suffolk Lay Subsidy as a member of the city Ipswich.

Socio- Economics

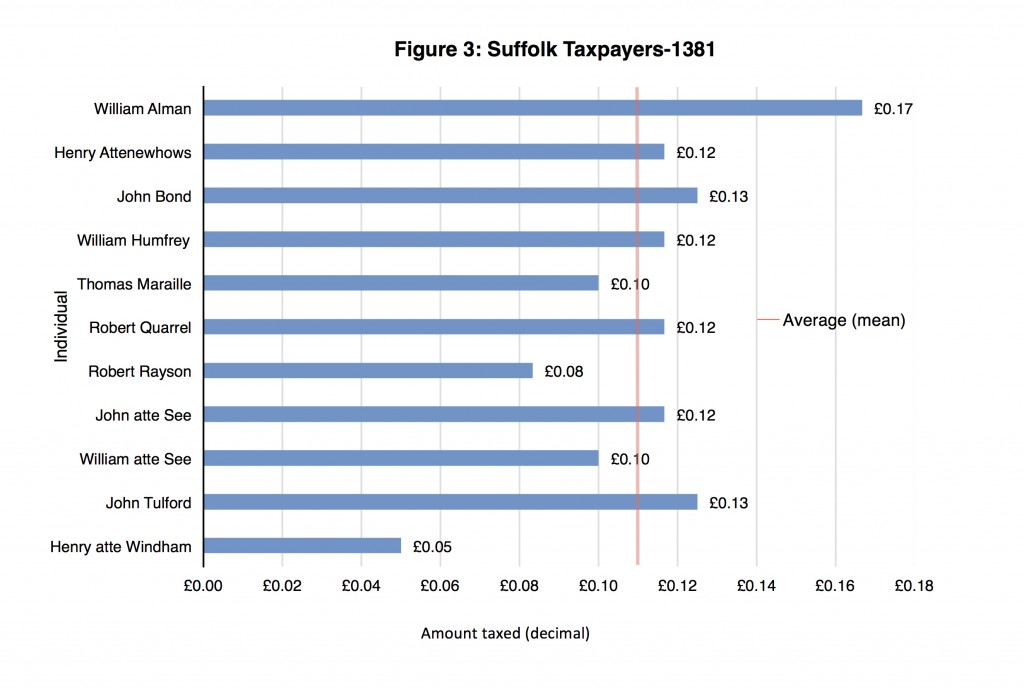

Of the 8,000 records of mariners found in the Chancery, Exchequer and other rolls, roughly 300 of those are unique Suffolk mariners. The Lay Subsidy from 1327 is the main source for Suffolk before the Black Death and the Poll Tax from 1381 for after the Black Death. From these 300 Suffolk mariners, 24 matches were found, which can be seen in Figure 2.

John de Whatefeldxiv is by far the richest man in Suffolk during 1327. While he sailed from Ipswich, he was taxed in 1327 for two properties roughly three miles outside Ipswich: one in Sproughton (2 s. )xv and one in Branford (6 s. 8 d. ),xvi perhaps explaining why he did not have a prominent career on shore in Ipswich. The next two richest men were Robert Gardinerxvii and John Irp.xviii Gardiner was taxed for three different properties all in the vicinity of his homeport Gosford: Bawdsey (2 s. ),xix Alderman (3 s. )xx and Boyton (8 d. ).xxi Irp, however, was taxed for only one property in Ipswich (5 s. 1.75 d. ),xxii making him the richest match who both sailed from and lived in Ipswich.

John Irp was a highly successful Ipswich mariner who maintained power both on the sea and on the land. Irp’s first appears in 1310 as a master of a ship sent to fight in the Scottish wars and later appears in 1319 when he is married.xxiii Irp served at either bailiff or coroner (sometimes both) every year from 1324 to 1347, as well as the controller of customs for Ipswich.xxiv A bailiff ’ s main job was to act as the executive officer, presiding over local courts; the coroner’s role was a supervisory one, intended to ensure the proper conduct of the bailiff.xxv Despite this illustrious land-based career, there are still records of a maintained life at sea: a navy payroll shows Irp sailing as ship master on the Godyer during Edward II ’ s campaign in St Sardos, in addition to a record that shows him evading customs charges.xxvi While Irp did lead a powerful life, there were moments of embarrassment. The prime example of this was in 1324. Irp, along with several other men, attacked a ship from Berwick in the port of Ipswich, despite it being under the ‘ safe conduct ’ of Robert de Umfraville, Earl of Angus, and stole its contents. However, this moment did not hinder his steady rise.xxvii By 1333, Irp held ‘ considerable local standing ’ as he was ‘ actively involved in loaning significant sums of money to other Ipswich residents ’ , as well as being ‘ called upon to witness several grants of lands and rents ’ .xxviii In 1338, Irp received a grant at the request of Queen Philippa that ‘ whereas the king lately granted to him the office of controller of customs at Ipswich, during pleasure, he shall hold the office during good behaviour ’ , which ensured he would remain the controller of customs.xxix Irp ’ s career did not end because of any wrongdoing on his part, but instead because of the Black Death, to which he fell victim to along with many others in 1348.xxx

Not all mariners appear in the Navy Payroll, or other records, as John Irp does. As was previously discussed, the English government changed the way taxes were collected in the later part of the fourteenth century. While they do eventually switch back to a lay subsidy system, the Poll Taxes do offer a wider range of information than the Lay Subsidies that came before them. For example, the Poll Taxes in 1379 and 1381 include occupational information on individual people when it was available, allowing for an expansion of the root database.xxxi One such person is William Alman from Benacre. He does not appear in the Exchequer, Chancery, or other rolls; however, because the 1381 Poll Tax has him listed as a piscat ’ , I was able to determine that he was involved in a maritime occupation. Piscat ’ is an abbreviated Latin word; it expands to piscator , which translates as ‘ fisherman ’ . These charts are the most basic way in which the Lay Subsidy and Poll Tax data can be used. In a larger context, this information can be used to compare seafarers between counties, as well as between occupations.

Cultural

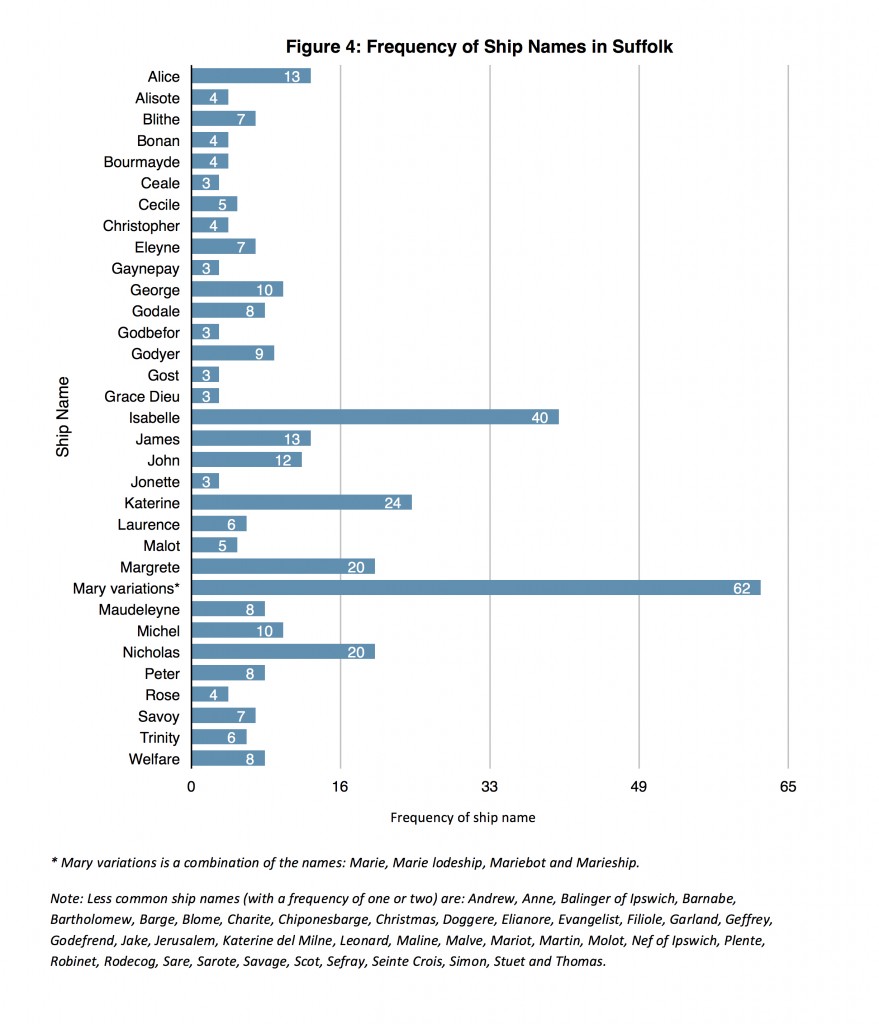

Defining the culture of an unobservable group can prove difficult for historians. What makes up fourteenth-century seafaring communities? There are a few different avenues that can be explored: the demography of the communities, the job distribution between men and women on land, and what objects are passed on through wills after death form one side that can be investigated. However, another side that is not often explored is that of the ship names chosen by ship owners and shipmasters. Ship names can open a window into the world of a fourteenth-century mariner by showing what is important to individuals. Is religion the largest aspect of this person ’ s life? If so, who are they calling on to protect their ship and its crew — a regional patron saint, an occupational patron saint, or a parish saint? If the ship name is not religious, then what does the person find important — a family member or a more personal motivation? Figure 4 shows the frequency of ship names in Suffolk. The most popular ship name is Mary, or a variation of this, with 62 instances of it in the database. The name Mary has connections to a variety of important religious figures: Mary the Mother of Christ and Mary of Magdalene being perhaps the two most important.

The Oxford English Dictionary describes the etymology of the name Mary. With roots in the Hebrew name Miriam, the name Mary has many different translations, some of which are associated with the sea.xxxii For example, St Jerome interpreted the name as stella maris or ‘ star of the sea ’ . Stella maris is used ‘ allusively of a protectress or a guiding spirit ’ and was first used by St Jerome in reference to the Virgin Mary in Liber de nominibus Hebraicis,xxxiii a fourth-century work that interpreted Hebrew names.xxxiv While never linked directly to the sea, the Virgin Mary as a guide and protector was a widely disseminated feeling.

Similarly, St. Mary Magdalene had widely-known links to maritime events, without ever having a direct link to sailors. Mary Magdalene was a follower of Christ, who told the Apostles of Christ ’ s resurrection. She was linked to Mary the sister of Martha of Bethany by Pope Gregory the Great, and therefore with Lazarus. Both of these connotations link her with idea of life and death, but the strongest connection she has with the sea is a metaphorical one: Mary Magdalene is often described as weeping, and the imagery of her tears is associated with the salt water of the sea. However, despite this, there are two voyage legends associated with Mary Magdalene that those living in the 14th century would have known. The first is a story about Mary Magdalene being set adrift off the coast of the Holy Land, but finding her way back to shore through Providence. The second story is of the Queen of Marseilles, who on her voyage to Rome dies in childbirth aboard the ship she is sailing on. However, St. Mary and St. Peter (a fisherman by birth) send another ship to their aid; this ship finds the mother and baby alive.xxxv

Other popular names have strong ties to a medieval seafaring community. St Christopher is not only the patron saint of travellers, but was also ‘ invoked against water, tempest, and plague and especially against sudden death ’ , all problems that these communities had to deal with.xxxvi St George had recently been chosen as the patron saint of the Order of the Garter, and was quickly being associated with Edward III and the Hundred Years War. The ship name George becomes more popular after its dissemination by Edward III.

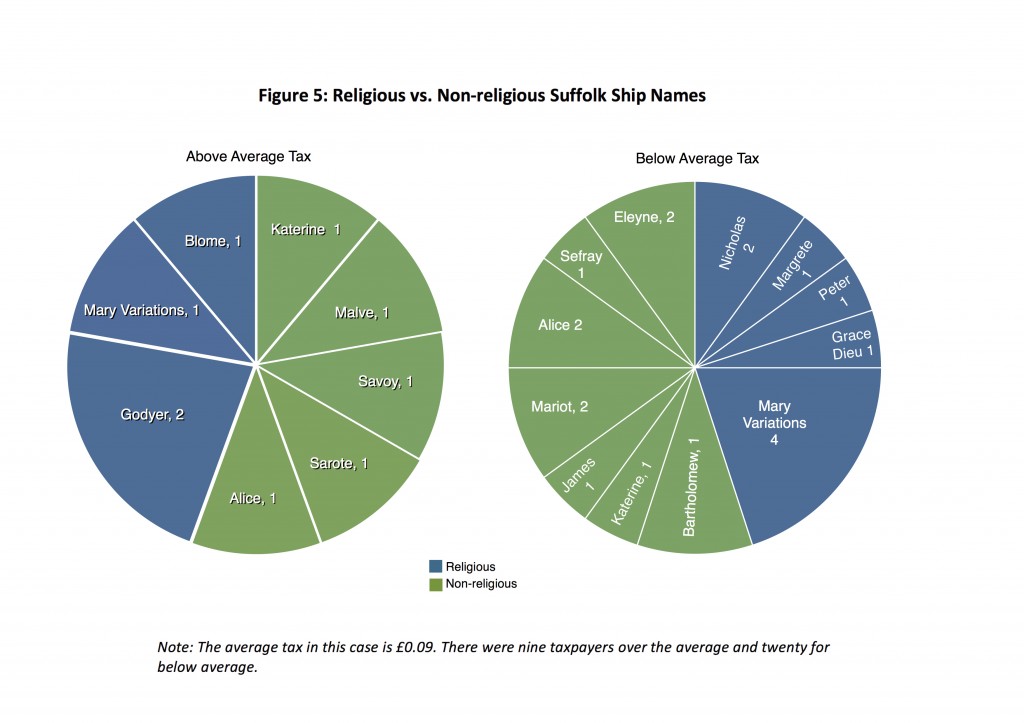

However, it is perhaps the non-saint names that are most interesting. The name Welfare appears eight times in Suffolk records and Gaynepay three times; appearing less frequently are Charite and Plente . All of these names suggest a personality trait or occupational trait that was important to the owner or master. The choice between religious and non-religious names can be investigated further by looking at the available tax information for the ship master, as can be seen in Figure 5.

Conclusion

It is possible to piece together a snapshot of seafaring communities by using all of the sources available, rather than relying too heavily on information from a single source. Fourteenth-century mariners were a complex group because of the unique nature of their work. My research on a larger scale hopes to take what this brief article does for Suffolk and apply it to all maritime counties in England.

Through the economic lens, it is possible to expand on what I ’ ve done here by creating a ‘ basket of goods ’ , in order to analyse more completely seafaring communities before and after the Black Death. Do those mariners who survive make more money as a result of the catastrophic losses seen over this period? Or does their wealth stay the same as a result of inflation? The work of Christopher Dyer and E. H. Phelps-Brown is essential to placing mariners in context with other members of society. Through a social lens, the careers of individual mariners are varied from county to county, and our history of these men is heavily influenced by the documents that survive — for obvious reasons. John Irp shows us that shipmasters did have careers on land; however, an investigation of influential shipmasters across England might show that this is not the case for all of them. The cultural lens is in many ways the most interesting part of the snapshot, as it is compiled from facts that are more open to interpretation. It is also something that can never be proved, only hypothesised. Rationales can be given to explain the choices these men made in the naming of their ships, but in the end it is impossible to know the real reasons behind them. However, it is through the combination of these viewpoints that a more complete narrative is created of this essential occupational group.