Jane Bowden-Dan provides us with the second article in our ‘Naval Medicine’ series. Greenwich Hospital always provided for mentally ill seamen, but the Royal Navy also sent patients to Bethlem, Hoxton House, or other private madhouses. Following the closure of Old Bethlem (or “Bedlam”) in 1815, the Admiralty opened a new lunatic asylum at Haslar in Gosport, inspired by a Quaker retreat which was the first to use ‘moral management’. This article considers confinement, the use of restraint, and possible maltreatment of seamen. At the naval lunatic asylum, new philosophies of mind, perceiving insanity as a somatic disease, offered the hope of a cure. This article is a revised version of a paper given by the author in the British Commission for Maritime History Seminar Series at King’s College London on 7 November 2013.

Madness – Manacles or Moral Management? Treating Insanity at Haslar Naval Lunatic Asylum

Introduction

The treatment of insanity at Haslar Naval Lunatic Asylum, which opened in 1818, is our subject. But before we go to Gosport, we must consider the late 18th century.

Distorted judgements on the treatment of the insane in Georgian England abound. The gradual disappearance of belief in devilish “possession” requiring extraction of ‘the Stone of Folly’, and its replacement by a brutal madhouse of ‘shit, straw and stench’ [1] is a cliché. Such a view is adopted from early 19th century reformers who neatly supposed that the period before their establishment of public asylums from 1808, was one of neglect or worse. There was, however, a change to thinking that insanity was a matter of public concern, at a time when the monarch himself – George III – suffered mental alienation and ultimately dementia.

Drowning at sea was a recurrent nightmare for the Georgians; and the Nation’s “Jolly Tars” – the sailors of the Georgian Navy – were of concern and appeared odd to those on land. Physician to the Fleet from 1779-83, Sir Gilbert Blane (1749-1834) thought that cases of insanity were seven times more common among sailors than among the general population.[2] Dr Roland Pietsch, University of New York in Berlin, has written and spoken about treatment at sea and sailors’ notions of masculinity. Using sea surgeons’ journals, he has offered possible explanations for the mental health issues affecting sailors of the Royal Navy in the 18th and 19th centuries: a youthful, heroic stereotype; trauma; diet; isolation; and especially alcohol. However, by 1800 naval surgeons worked not only afloat, but, increasingly, on dry land, at naval hospitals and infirmaries at home and abroad. The largest of these was the Royal Naval Hospital at Haslar, part of which in 1818 was set apart for insane officers and seamen.

To illustrate earlier work on how ideas of health and disease affected the ‘wooden world’ of Nelson’s navy I used a well-known cartoon, by James Gillray (1757-1815). ‘Extirpation of the Plagues of Egypt;- Destruction of Revolutionary Crocodiles; -or- The British Hero cleansing the Mouth of the Nile’ is a political interpretation of the Battle of the Nile, 1 August 1798, and the capture of French Prizes (though the French flagship L’Orient explodes dramatically in the middle distance on the right). Britain’s new hero, Horatio Nelson, brandishing his club of ‘British Oak’, wades knee-deep across Aboukir Bay disciplining the ‘Plagues of Egypt’ of the print’s title, represented as French tricoloured, but weeping, ‘Revolutionary Crocodiles’. Gillray uses metaphors of disease and hygiene.

Developments begun during the period of victories of the so-called Seven Years’ War (1754-63) brought the Royal Navy its fighting superiority in the age of Nelson. Gradual medical developments over the same period gave it one other vital advantage over its rivals – relative good health. Disease remained the greatest threat to the lives of seamen throughout the French Revolutionary Wars, but the British fleets maintained the best fed, cleanest and best disciplined crews afloat. By modern standards, the lives of officers and ratings remained brutish and short, but they were generally less unpleasant and longer than those of their foreign counterparts.

However, were any medical developments at this time in the treatment of the insane, significant? What were the implications for the massively-expanding British Navy of new ideas about madness? Were new forms of discipline itself, associated with medicine, being created in the Navy?

Early industrial society had already developed a variety of ad hoc expedients and institutions for handling the insane. It also employed an eclectic range of therapies.[3] The life work of Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802) for example should make us hesitate before claiming that the mad were treated brutally or that there was no ‘psychology’. Darwin was the foremost physician in the English Midlands, a leading medical author, educationalist, scientist and best-selling poet. He used digitalis from foxglove as an anti-maniacal, and even derived a ‘rotative couch’ from Brindley’s mill-stone. Watt made a detailed engineering design using Darwin’s specification for this whirling chair, intended to dispel alienating thoughts. Darwin was a founder member of the Lunar Society of Birmingham, an English coterie of philosophes who celebrated progress, deplored slavery, and, for the most part, saluted the advent of the French Revolution.[4]

The status of insanity and demarcating the insane

Michel Foucault (1926-86) the French philosopher suggested that madness was invented in the ‘Age of Reason’ to stigmatise unreason.[5] Foucault had an undifferentiated view of insanity; although there was, in fact, considerable interest in its different forms.[6] The Georgians’ interest is evidenced by the very popularity of Bethlem (popularly called “Bedlam”) as a public resort. Bethlem encouraged ‘penny visiting’, which was more than casual morbid curiosity, allowing the public to see inmates, and view treatments such as bloodletting, cold baths and drugging.[7] Before the Admiralty converted F Block of the Royal Naval Hospital at Haslar, in Gosport, for lunatic patients in 1818, some officers and seamen were sent to Bethlem. Dr Martin Wilcox of Greenwich Maritime Institute let me view, pre-publication, his recent work on the “Poor Decayed Seamen” of the Royal Hospital for Seamen at Greenwich, commonly known as Greenwich Hospital. Dr Wilcox’s Database, covering 1705-63, suggests the poor mental health of some pensioners. Some of the apparent cases of madness had almost certainly suffered psychological damage of the kind hinted at by Jeremiah Raven, which we would now call Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: “The Invisible Wound”. Raven was expelled from Greenwich Hospital in October 1756 after suffering periodic “fits” of insanity, during which he became violent and disruptive. He attributed his illness to a fire in the spirit room of the fourth-rate HM Ship Dragon (60), in which one of his messmates had burned to death.[8]

We can infer that widespread psychological damage, which we would now call PTSD, arose from intense, prolonged engagements at sea. An example would be the ferocious night action off the Spanish Mediterranean port of Cartagena on 28th February 1758. The engagement started at 8pm and went on until gone midnight, probably 1am. The 80-gun Foudroyant – sailing from Toulon was then the flagship of the French Rear-Admiral Duquesne de Menneville (the former Governor-General of New France, now Canada, who had done so much to start the war). Foudroyant had also been the French flagship at Minorca. Captain Gardiner of the smaller, third-rate HM Ship Monmouth (66) had been the unfortunate Admiral Byng’s flag-captain at Minorca. Dr Nicholas Rodger says that Gardiner “redeemed his honour with his life”, and that the capture of the Foudroyant did much to restore the Royal Navy’s reputation at a pivotal time.

But the price was high: the British ship suffered 30 killed, including Captain Gardiner, and 80 wounded. Foudroyant had 139 killed. Seventy, yes 70, broadsides, or broadside-equivalents were fired by Monmouth alone; representing 1,944 lbs of shot, against the Foudroyant’s 1,164 lbs.; fired at times from a distance of considerably less than 100 yards. We may scarcely imagine the possible psychological effects of deafness from the concussion of the guns.

But Greenwich Hospital had “no convenience for lunaticks” in the words of the Directors writing to the Governors of Bethlem.[9] Nine men in Dr Wilcox’s Database are recorded as having died at Bethlem, which does not include those who were sent there from Greenwich Hospital on a temporary basis. Nor, as we shall see, was Bethlem the only insane asylum used.

This print of 1735 of the concluding scene of William Hogarth’s (1697-1764) The Rake’s Progress (1733) shows the ‘penny visiting’ (by two fashionably-dressed young ladies0 at Bethlem, and the dissolute Tom Rakewell’s final descent into madness. One of the other inmates, who are all suffering various delusions, is an ‘astronomer’. He may be attempting to solve the long-running longitude problem. He is shown staring fixedly at a drawing he has scratched on to the back wall of a globe marked with lines of latitude and longitude. A fellow patient has made a paper telescope (perhaps for measuring lunar distances, or making other celestial observations). Indeed, “longitude lunatic” became popular slang for anyone who was deluded. Seamen from the Royal Navy – then the largest employer – were not only over-represented in the category of men who had no family, but also as inmates of Bethlem.

Their treatment at that institution was delivered in bespoke premises on the line of London’s city wall at Moorfields, in a bizarre Baroque masterpiece. In 1815 the hospital moved from Moorfields to a new building in St George’s Fields, now the Imperial War Museum, when the prevailing aim was to abolish, if possible, mechanical means of restraining aggressive patients.

A little more about Greenwich Hospital: inevitably some older, mentally ill seamen – possibly with what we would now call senile dementia – were lucky enough to have pensioner places at the Royal Hospital at Greenwich – established in 1694 – “British sea power in stone” (according to Professor Eric Grove). Fig 2 is a somewhat fanciful image of a Pensioner by Charles Castle from the early 19th century.

Fig 2 © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London (PAD 2210)

First Lord of the Admiralty, John Montagu (1718-92), 4th Earl of Sandwich, had sponsored the Infirmary at Greenwich. Best known for her affair with Lord Sandwich, was Martha Ray (1743-7 April 1779), a talented singer. She lived with Lord Sandwich as his mistress, and gave birth to five children, while Lord Sandwich’s wife was suffering from mental illness. Ray was murdered by a soldier-turned-clergyman, James Hackman, who was infatuated with her. The events surrounding the murder were used in the popular novel Love and Madness (1780) by Sir Herbert Croft (1751-1816).

So, Georgians, and then Victorians, had little difficulty in accepting that lunacy existed as a generic reality, yet actually demarcating the insane often remained controversial in individual cases. Standard types: the jilted lover gone demented; the tramp; or the ranting religious maniac, epitomised insanity in the public mind. For most people, madness was still conceived more in terms of deeds and demeanour, than of disease or any permanent disposition. A gamut of conditions was recognised from mere melancholy to mania and complete madness.

Confinement and maltreatment

Harmless lunatics were traditionally left alone to experience the most solitary and alienating of afflictions.[10] Authority intervened only when insanity’s public presence became a threat.[11] Although it is hard to be precise, by 1800 no more than about 5,000, ‘lunatics’ were confined in England in all establishments.

Hoxton House (Miles’s), Shoreditch, east London

The conditions in Bethlem were perceived as savage even by contemporaries. Parishes were also regularly boarding-out lunatics in private dwelling houses. During the reign of George II (1727-60), as population grew, the number of these private madhouses increased steadily. They were founded on the principle of profit (perceived by some as a basic flaw) and “the trade in lunacy” also acquired a reputation for corrupt and brutal practices.[12]

Accordingly, an Act of 1774 made provision for the licensing and inspection of private madhouses. Printed advertisements for them are a rewarding source of information about conditions. The principle of “no cure – no money” was a popular one. Early cure and the use of kindness are referred to in late 18th examples, such as an advertisement for Joanna Harris’ madhouse at Hook Norton from Jackson’s Oxford Journal, 1778. She refers to family tradition, an assistant surgeon-apothecary, and the use of “the utmost Tenderness”. The restoration of the lunatic was the primary objective in many private madhouses from the second half of the 18th century.[13]

The official use of licensed madhouses for naval and military lunatics is notable. From 1791 and probably earlier, contracts were made by the Admiralty for the confinement of insane officers and seamen of the Royal Navy at Hoxton House (Miles’s), near Shoreditch Church, east London. This was a large brick building with quite extensive grounds for patients’ exercise, surrounded by market gardens. Miles’s business of handling naval lunatics, whose care was underwritten by the State, grew extraordinarily large. Until 1814, the Navy conveyed 10-20 new patients there a year.

Batavia Hospital Ship

Moored in the Thames, off Woolwich, the Batavia Hospital Ship – a hulk -received “naval maniacs” from Hoxton House when they were considered fit for convalescence. The only documents relating to the Hospital Ship, which I have seen so far, are poignant burial records for February 1814 at Woolwich, Kent for two men, aged 37 & 40. Their “abode” is described as “Hospital Ship Batavier”.

Poor Conditions

In 1812, Dr John Weir, Inspector of Naval Hospitals, had revealed poor accommodation and treatment at Hoxton House. He recommended the erection of a hospital specifically for naval lunatics.[14]

An enquiry into the regulation of madhouses was then conducted by a House of Commons’ Select Committee, which confirmed, in its Report of July 1815, the existence of exceedingly bad conditions for naval lunatics at Hoxton House. At that time, the naval contingent there comprised 14 officers and 136 seamen and marines.[15]

Haslar Lunatic Asylum

So, in 1818, part of the existing Royal Naval Hospital at Haslar was set apart for insane officers and seamen. The Haslar site had been bought in 1745. It is a glorious 55 acres in Gosport overlooking the mouth of Portsmouth harbour, on the west side. After what was then the biggest construction project in the Country, costing £100,000, the first purpose-built hospital for the Royal Navy was opened from 1754, and took some 1,800 patients.

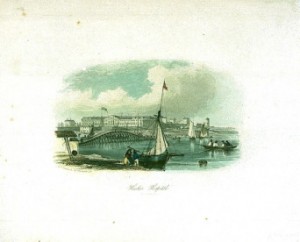

Fig 3 Engraving by J & F Harwood © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London (PAD 1074)

This is a (slightly foxed) engraving of an 18th century vignette of the Naval Hospital. Its distinctive high brick walls were to prevent escape, and the expression “up the creek” refers to Haslar Creek, which was not a good place to be! Nevertheless, late 18th century Haslar was described as “one of the medical wonders of the age”.[16]

Relatives of naval officers removed from Hoxton House to Haslar Lunatic Asylum appreciated that the treatment was better, but were distressed when deductions from pensions were made as a contribution to costs [Hansard 16 July 1844].

What was the treatment at Haslar like? Reformers introduced a new atmosphere of kindness into asylums, but did not forswear restraint. Darwin was familiar with the problem, and his own clinical experience showed that coercion was sometimes salutary. As he put it: ‘Where maniacs are outrageous, there can be no doubt but coercion is necessary: which maybe done by means of a straight waistcoat; ….’[17]

Fig 4 shows ‘James Norris shackled at Bedlam sketched from life by G. Arnald in 1814 …’ the etching by George Crickshank. The story of Norris, a seaman from America, who had been kept chained to his bed in Bethlem for ten years, aroused public anger and was instrumental in leading to the Mad Houses Act 1828 which aimed to regulate the treatment of the insane.

Darwin had argued that in some cases of insanity confinement worked, whereas:

In others there can be no doubt, but that confinement retards rather than promotes their cure; which is forwarded by change of ideas in consequence of change of place and of objects, as by travelling or sailing.[18]

Moral management (later called ‘moral therapy’)

By the early 19th century, spectacular punishment in the Navy was being replaced by confinement, and the use of medical examination to ensure order. Two of the most vicious physical punishments in the Navy were, officially, abolished: ‘running the gauntlet’ in 1806, and, in 1809 ‘starting’ (informal on the spot beating with a single rope or ‘colt’). There are parallels with the creation in the late 18th century of what contemporary English physicians called ‘moral management’ for the insane. It embraced the therapeutic optimism of the Enlightenment, and aimed to displace cruelty with humanity. Treatment focused on the individual, and did not use drugging or traditional medical techniques such as bleeding and purging.

Moral management set the pattern for the better sort of madhouse: small communities with a domestic atmosphere in which there was a mixture of support and manipulation. In 1796 a new model asylum – the Retreat – was opened for Quakers at York by the Tukes, tea merchants by profession. Management there: ‘almost entirely by reason and kindness’, was admired by a Swiss-American traveller. However, the Tukes, like other moral managers, also believed in the therapeutic power of fear. Immediate rewards and punishments were used as if the patients were children. Foucault interpreted this moral management as a ‘gigantic moral imprisonment’. The Retreat could, he suggested, do away with manacles of iron, because it was enclosing patients in ‘mind-forg’d manacles’ (a quotation from Blake).[19] Foucault’s comments were wilful in view of the York Retreat’s successful restoration of many patients to normal social life.[20]

Conditions in Haslar Naval Lunatic Asylum

At the Royal Society of Medicine, I read an intriguing account of ‘A Visit to Haslar in 1916’, written by Major-General John Richardson, then retired and aged 78. His father ‘Old John’ was the Inspector, and the writer was a one-month old baby when first taken to live in the official residence at the Royal Naval Hospital Haslar. Although the late Richard Holmes tended to avoid drawing on the reminiscences of veterans, mindful of the frailties of human recall; childhood memories can often remain vivid and accurate. So, I shall quote from Richardson’s journal article:

‘On the other side of garden lay the grounds of the lunatic asylum. These and their inmates had a strange fascination for me. When my father first went to Haslar, the asylum was under the charge of a medical officer who apparently held the view that lunacy could be cured or controlled only by the administration of severe disciplinary measures. My father was vexed with what he saw, so he made trips to London and elsewhere to study the latest methods for the treatment of insanity. Before long the medical officer retired.’

‘Dr Anderson came, one of the kindest of men. In spite of opposition, a remarkable change soon came over the methods of treatment in the asylum. Of course there were several dangerous lunatics, but some were found sane and others proved amenable to kindness. Several rough attendants were discharged.’

‘The poor men were gradually given more liberty, and nothing untoward occurred. More grounds were made available, and in these a mound was thrown up and a look-out made where the men could see Spithead and the ships, which they were never tired of identifying. A boat was provided for the use of the lunatics, and in favourable tides and weather, crews of these poor men rowed out to Spithead and fished. Very excellent fishermen some of them were too. I was often out with them, catching whiting, congers, sole and plaice. ….A patient took charge …’

‘As soon as the lunatics were let out of the wards in the morning, some of them took up set places in the grounds. One poor fellow for years occupied a corner under our garden wall, where he swayed incessantly from one leg to the other. The men never seemed to quarrel or interfere with each other’s “pitches”, but they occasionally knocked down an attendant who was cruel to them, when they were, in the early days, punished with blows, solitary confinement, and straight-waistcoats.’[21 & 22]

The letterbook of William Burnett, Comptroller of Victualling, contains memoranda about Haslar Naval Lunatic Asylum. One describes how:

‘the patients tended fruit and vegetables cultivated in the gardens with obvious therapeutic benefit, and annual saving of up to £100 in hospital provisions.’

[The National Archives, ADM105/70 page 101 – 21 October 1833]

The therapeutic effects of cooking were also used.

Haslar cemetery

Many of Haslar’s patients would have died in the Hospital. In about 2009, before redevelopment of the entire site, Cranfield Forensic Institute of Archaeology excavated a small part of the burial field, and estimated that the whole contained a closely-packed total of nearly 8,000 corpses. There were no headstones, coffin plates, or fragments of uniform to enable individual identification. The men were probably buried in shrouds, possibly made from their sailors’ hammocks.

The sample of 30 skeletons excavated revealed that, quite regularly, Haslar’s surgeons had performed autopsies, including the removal of a cranium with a sharp knife or wire. Naval Surgeons were in the vanguard of medicine, and the Royal Navy was always an ‘early adopter’ of new ideas, in the words of Dr Kevin Brown, Curator of the Alexander Fleming Museum. Though it might seem shocking that post-mortems were common, they did give surgeons and physicians the opportunity to study diseases, possibly even ‘head-cases’; at a time when, before the Anatomy Act 1832, such dissection was strictly illegal. Medical Schools were allowed only a few bodies from the gallows per year for anatomy.[23]

Conclusion

I have shown the emergent sympathy towards the insane from the end of the 18th century. It may be explained as part of the growth in individualism, subjectivity and sentiment during the Enlightenment. Explanations of insanity were offered, and the hope of cure to patients (even at Bethlem).

However we have just seen, specifically, that in the spirit of scientific enquiry in the Age of Reason, the somatic cause of unreason was, seemingly, investigated by illegal autopsy, within a Royal Navy which was an ‘early adopter’ of new ideas. More generally, Enlightenment vision failed to prevent the construction in the Victorian era of vast, utilitarian institutions; and the mental health problems of those are still with us.

© J E Bowden-Dan 2013

References

1. Scull A. The Domestication of Madness. Medical History 1983;27:234.

2. Lewis M. A Social History of the Navy 1793-1815. London; 1960. 396-7. One in 1,000, instead of one in 7,000; see Blane G. Statements of the comparative health of the British Navy from the year 1779 to the year 1814, with proposals for its further improvement. Medico-Chirurgical Transactions. 1815. 564-5.

3. Porter R. Mind-Forg’d Manacles: A history of madness in England from the Restoration to the Regency. London: Penguin Group; 1990. 278.

4. McNeil M. Under the Banner of Science: Erasmus Darwin and his Age. Manchester: Manchester University Press; 1987.

5. Foucault M. Folie et Déraison: ….translated and abridged as Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. New York: Random House; 1965. 39.

6. Micale MS. Approaching Hysteria: Disease and its Interpretations. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1973. 99.

7. Andrews J. ‘Hardly a Hospital, but a Charity for Pauper Lunatics’ ?: Therapeutics at Bethlem in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in Barry J. and Jones C., editors. Medicine and Charity Before the Welfare State. London: Routledge; 1991. 65. In this period, “drugging” at Bethlem would have meant the use of a variety of laxatives. Treatment with the ‘old standby blank cartridges’ of chloral mixtures and bromide was not introduced until the 19th century.

8. The National Archives [TNA], ADM 65/81 Petition, undated.

9. TNA, ADM 66/28, Directors to the Governors of Bethlem Hospital, 11 Jul 1730

10. Scull A. The Most Solitary of Afflictions: Madness and Society in Britain, 1700-1900. New Haven and London: Yale University Press; 1993.

11. Porter R. Mind-Forg’d Manacles: A history of madness in England from the Restoration to the Regency. London: Penguin Group; 1990. 38.

12. Parry-Jones WL. The Trade in Lunacy: A Study of Private Madhouses in England in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; 1972. Intro. 9 and Ch 3, 29-31 & 36.

13. Parry-Jones WL. The Trade in Lunacy: A Study of Private Madhouses in England in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; 1972. 102 & 168.

14. Report to the Commissioners of Transports, 13 Nov. 1812, ‘Remarks on the management of such officers, seamen, and marines, belonging to His Majesty’s Naval Service, and of such prisoners of war, as are admitted into the house of Messrs Miles & Co. of Hoxton, for the cure of mental derangement.’ In Papers relating to the management of insane officers, seamen, and marines, belonging to His Majesty’s Naval Service, 1814.

15. Andrews J. and Scull A. Undertaker of the Mind: John Monro and Mad-Doctoring in Eighteenth Century England. London: [publisher], 2001. 153, 161-161. Parry-Jones WL. The Trade in Lunacy: A Study of Private Madhouses in England in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; 1972. 67-68.

16. Vale B. and Edwards G. Physician to the Fleet: The Life and Times of Thomas Trotter, 1760-1832. Woodbridge, Suffolk and Rochester, NY: Boydell Press, 2011. Foreword ix.

17. Darwin E. Zoonomia; or, The Laws of Organic Life, vol I. London: J. Johnson; 1794. 352.

18. Darwin E. Zoonomia; or, The Laws of Organic Life, vol I. London: J. Johnson; 1794. 352. Porter R. Mind-Forg’d Manacles: A history of madness in England from the Restoration to the Regency. London: Penguin Group;1990. 215-216.

19. Foucault M. Folie et Déraison: ….translated and abridged as Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. New York: Random House; 1965. 243 & 278.

20. Porter R. Mind-Forg’d Manacles: A history of madness in England from the Restoration to the Regency. London: Penguin Group; 1990. 225.

21. Richardson J. A Visit to Haslar, 1916. Journal of the Royal Naval Medical Service. 1916. 2, 329-339.

22. McLean D. Surgeons of the Fleet: The Royal Navy and its Medics from Traflagar to Jutland. London: I.B. Tauris; 2010. 100-104. Richardson J. A Visit to Haslar, 1916.

23. Richardson R. Death, Dissection and the Destitute. London: Phoenix Press; 2001. Intro. xv.

This was a very interesting and well-written article. I have just discovered that my Great Grandfather (1851-1931) was a coastguard in Kent (1879-1889) and was interned, after his discharge, in the Royal Naval Hospital at Great Yarmouth. He remained there for 40 years until his death, His wife and 5 children were left to fend for themselves, and they never saw him again. The reason for his internment remains unclear. I hope to find out more.

I wonder if there exists a similar article about the Great Yarmouth R.N. Hospital?