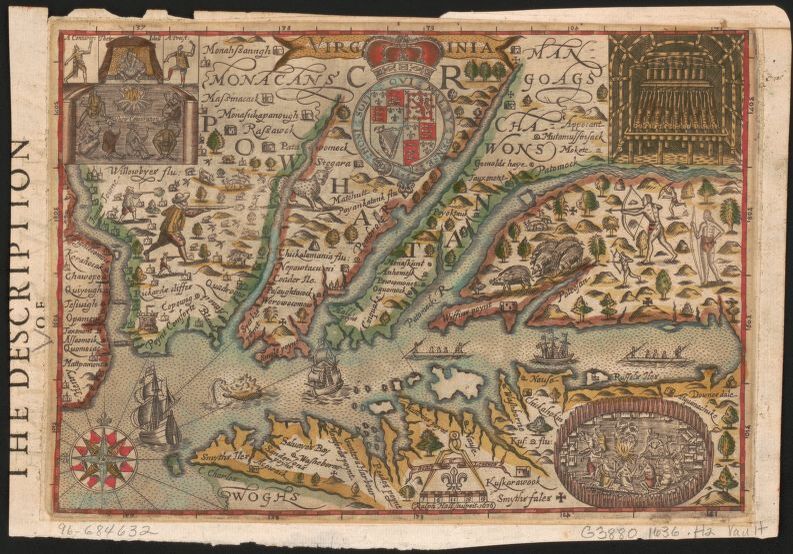

Virginia map by Ralp Hall c 1637. Credit Library of Congress Item Call Number G3880 1636 .H2

Nearly everything that was taken to and from the colony is repeatedly described, sometimes in detail, in primary and secondary historical sources as coming from aboard vessels. The Virginia Company of London’s business records, the Jamestown colonists’ trade with Indians, colonists’ personal belongings and merchants’ goods coming to Virginia from England, market products shipped from the colony to British and European ports to sell, colonial military armor and weapons, munitions, servants, slaves, livestock, letters to and from home, etc. had to get from the ship in the James River to the shore of the Colony on Jamestown Island or from the land to the ship. The ships sailing on behalf of the Company were merchantmen or merchant ships.2 Some, but not all, were among the largest of the English merchant fleet. Loaded merchantmen, upon arrival at the colony, had to sail from the Atlantic Ocean and up the James River to deliver cargo at Jamestown. These laden down and seafaring vessels were not riverboats and required a significant depth of water to allow for the submerged portion of the ship (called the ship’s draft). To get the ships’ cargo into Jamestown Colony on the island, they had to be able to sail close enough to shore where, in the James River, the draft could be accommodated and the ship could be moored and unloaded while at anchor in the James. Percy’s description suggests to those first colonists this was a factor, if not the factor, that determined their selecting the island that became Jamestown.

On that first day there, George Percy may have jumped from the ship onto Jamestown Island, but as the colony grew, increasing amounts of cargo meant English lighter boats (a kind of river barge) or shallops would have carried and ferried cargo from ship to shore or the reverse. But to unload and load cargo like livestock, victuals, or tobacco and other items of great volume and weight, a dock, wharf, or waterfront, certainly a wooden wharf-side crane, in the James, at deep enough water, would have been particularly valuable – especially to a joint-stock company whose colony was expected to make money, such as the Virginia Company of London’s Jamestown Colony.

The findings from archaeological studies of other early 1600’s (also called the Early Modern Era) English colonies’ waterfronts, contemporary to Jamestown, like English Newfoundland3 or Fort George in Popham’s Colony, Maine4, demonstrate that today, four hundred years later, archaeological evidence of English colonial waterfront features have been discovered, and so may also yet exist within and along the James River in proximity to the Jamestown Colony historical site.

An archaeological discovery of a feature (an archaeological term for an historical structure) like an early Jamestown dock or pier, if proven to have indeed been part of the early Jamestown waterfront, would be evidence of the very first permanent English shipping commerce site in America. Particularly if it is associated with Jamestown, according to The National Register of Historic Places’s historical nomination site criteria, that feature (or historical site) would likely be of high significance.5

Virginia Company of London Seal

Besides recognizing the importance of an historical waterfront feature’s site, if found and placed onto the National Register, the new information that could be learned from the study of such a site would increase what we currently understand about the early Jamestown Colony’s fort and waterfront placement and site arrangement, shipping commerce, and waterside construction. In addition, we would potentially learn more about what occurred on such necessary infrastructure, like a waterfront, during the Jamestown Colony’s first three decades, or Company years. For example, if a Powhatan canoe was to be uncovered in the clay bed of the James, near the Colony site, dating to this period and indicated from artifacts or historical structures’ diagnostic features that it was in use by the colonists (rather than Indians), the colonial English use of a James River Indian’s canoe, for instance, would reveal surprising new information about English and Native relationships and trade. As another example, English, Dutch, or Spanish anchors dated to the era of exploration (before Jamestown) but possibly also still in the James, today, could tell us more about this earlier European exploration. Or, if a larger Jamestown era anchor was discovered off the island it could reveal where the English merchantmen sat at anchor (if more than one – perhaps in numbers) in the James in front of the colony, and when. Also, the volume of commerce could be better understood if different kinds of cargo or its containers, dated to the period, were found, and so on. As a tool, the earliest English James River colonial commerce records still in existence can describe for archaeologists what types of historical vessels, boats, materials, trade goods, etc. typical of the period may be found; possible site locations and identification clues; historical context; and can help interpret findings.

APVA Preservation VA Jamestown Rediscovery Excavation in 2007of Building Foundation. Source Colonial Williamsburg A Teachers Guide Col Jamestown Unearthed PDF page4.

So, what have historical documents and the archaeological record revealed so far about an early 17th century colonial Jamestown waterfront or port during the Colony’s Company years?

Of the cross-Atlantic business and embarkation process detailed in a portion of the transcribed court minutes dated “1623 December 11th … Capt. Barwick [said] that Capt. Sampson sayth that upon a report that all was delivered some 2 tuns of his goodes aboard the the Furtherance …” to three different men in Virginia from England: cider, ammunition, shoes, butter, sugar, Aquavitae, and from the Company: pitch, tar, tools, and pails. Placed aboard another ship, tobacco was the cargo that “…was sent home in the Temperance …” A business process, likely conducted at or upon the Jamestown waterfront, is explained: in order for goods to be received aboard ship “… at the packing up of those sayd goodes …” a ticket from the Virginia Company was required. Captain Barwick at first did not have it so the intended cargo was not allowed on board. After he obtained the ticket days later, Barwick gave it to Captain Sampson, and then the cargo was allowed to be loaded and Sampson “… did receave it aboard …” described as 2 hogsheads of tobacco packed with 220 pounds weight tobacco to ‘sail home for England’. Of the Company’s pitch, tar, tools, and pails described earlier, “[sic. Mr.] Nun sayth that he was at the packing up of those sayd goodes kept in the lighter w[hich] were the lighter of goods which were pitch & tare & certyane tooles & payles which did belong to the Company.”7

Shallop btw pgs 32 and 33 from Some Notes On Shipbuilding and Shipping In Colonial Virginia by Cerinda W. Evans 1957.

In this last historical record, is now the first mention of servants, so critical to the Virginia Company of London’s financial goals, and involves a dispute heard by the court “… held 9th of March 1623[/4]” (McIlwaine 1911, 146). A servant, Richard Grove, testified that he was initially promised or bound into service to a Mr. Proctor but during their voyage together from England to America, Grove wound up serving a Mr. Horne aboard ship and “… since they came ashore …”, at Jamestown, Grove understood from Horne his servitude was, in the colony, instead to be to Horne, confusing Grove, and leaving Proctor without a servant. The first witness, “Phetty place Close … acknowledged that the goodes that were Mr. Horne demandeth of Mr. proctor are Mr. Hornes[.]” The second witness, Thomas Flower, clarified for the court that before they were about to sail for America,“… Mr. Horne had furnished a man to come for this Countrie & when they were ready to come away he told Mr. Proctor that his man was sicke, to w[hich] Mr. Proctor said that he take no care for a man if you wilbe ruled by me youe shall have one of my men when we come to Virginia[.]” Fortunately a solution was reached. “Itt is agreed by the consent of both p[ar]ties that Thomas Flow shalbe assigned o[ver] to Henry Horn for 3 yeares provided that if the said Henery Horne do propose to give him out or assigne him to another Mr. Proctor [shall] have the refusell of him paying as an other will …”(McIlwaine 1911, 146-147).9

These quotes from portions of just a few Jamestown shipping records reveal a variety of trade partners, trade goods, and the kinds of business transactions that happened, some of which apparently occurred during or around the time they disembarked.

Yet very little archaeological work has been done underwater, in the riverbed, or under the shore near Jamestown or near any of Jamestown Colony’s early towns and plants.

In fact, only three underwater or waterfront archaeological sites are listed as ‘in or around the James River’, in the State of Virginia’s most recent public underwater archaeology Report.10 It is understandable that to protect them from looters the location of these three “James River” sites’ is not made clear. But they are dated “1607-1750” – a date range so broad that, to the reader, none of the three sites can indicate for Jamestown’s era at all. For example, during this particular set of 150 years the following occurred: the founding of Jamestown; the expansion of and European settlement down the entire American eastern seaboard; the first western migration into and settlement of an American frontier; and finally, the decades leading up to the American Revolution. Considering the extent of early American history that happened during this range of years, that only three underwater James River archaeological sites are recorded is surprisingly low.11

What’s more, the Report’s authors acknowledge this. “The number of recorded sites that are truly submerged is pitifully small, especially knowing what the total number must really be” (Blanton 1994, 3).

Historic Jamestowne Map Of Discoveries as of 02/05/2020.

But some archaeological research has been done. “Unlike [sic. Capt. John] Smith’s account, George Percy’s narrative documented the Starving Time in great detail from first-hand experiences, and archeological evidence supports many of his claims—including cannibalism.”13 Percy’s quote, above, about tying the first Virginia Company ships to trees on the edge of the Island appears to have also been proven likely. Moreover, these and other studies (each to be discussed next), suggest even wooden artifacts and historical features such as early 17th century English piers, docks, or wharfs, cranes, or warehouses that might have existed as part of a Company Jamestown waterfront could still be present, even intact or mostly intact, under the James, today.

In 1900 and 1901, Civil Engineer, Samuel H. Yonge was hired by the United States Engineer Department, a federal agency (and a precursor to today’s U.S. Army Corps of Engineers) to protect Jamestown from being further swept away by the James River. The island was undergoing physical changes that undermined and appeared to wash away or drown historical ruins and sites that existed at the shore. Yonge wrote of the historical investigation during his conservation project, “… the protection work … led to making personal researches among all available sources of information, which have occupied the leisure moments of a period of two years.”14

During his preservation effort, Yonge found the James River’s wave action abrasion upon the island was causing the erosion or loss of historical sites (Yonge 1904, 257). It is important to point out that until there is a systematic detailed geoarchaeological and hydrological study of the changing shoreline in and around Jamestown Island, it remains and will remain unknown whether any Jamestown historical features, sites, or artifacts moved, and if they moved where they may have ‘landed’ or could be today. No one can say for certain what is or is not now there until a systematic, detailed, and thorough scientific archaeological investigation is conducted. Yonge’s was not this kind of study but, it turns out, we can see today that it was a beginning. Of Jamestown’s specific site within the James River Yonge wrote,

These findings are important. Yonge wrote that while the James’ riverbed was probably eroded a bit in the 300 years between the settling of Jamestown and his 1901 study, at the sides of the river (i.e. the river’s edges at the shoreline), he found little geological evidence of physical change. So, according to Yonge’s assertion, the idea that any cultural or historical evidence that may have once been there was completely swept away is not certain.

Too, he finds that there was once an extended peninsula or sliver of land that protruded from the island and extended out into the deepest channel of the James River, in front of Jamestown Island, in the 17th century. This is interesting; given George Percy’s written account of tying ships to trees on the island’s shore and that shore being near 6 fathoms of water. Yonge continues,

The map that Yonge produced for the U.S. Engineer Department during this preservation contract is perhaps the only modern professionally surveyed map that includes original early Jamestown land grant survey lines of parcels issued to individuals. One of the three early English forts and sounding depths leading away from the island into the river’s main channel are also mapped. Yonge includes this nautical information about the James in his map because, as he wrote, an early Jamestown unloading site (perhaps a waterfront) may have existed at the end of a promontory or peninsula, the end of which he believes met the deepest channel of the James that existed during the 17th century (Yonge 1904, 258-262). On his map, this spot is shown where, just off the island, fathoms lines meet (topographically depicting steepness).

Said another way, an early English dock or pier (or more) could have been built at the end of a point of dry land extending out into the James off the island (forming a natural causeway), the end of the point being out in the river against where the depths of the river was then enough for the draft of even the largest English merchantmen, full of cargo and people, to sit at anchor while being unloaded.

In fact, as recently as 1807 the shape of the landscape immediately before the Island and Jamestown site was described as, ““… a beautiful cove in the form of a crescent, which stretching on either side afforded a safe and expanded bason [sic. basin]”” (Yonge 1904, 269). No cove is visible, there, today.

We do know today that Yonge correctly estimated, among other things, the site of the then not yet located, first Jamestown Fort.

A circa 1617 map of the James River, attributed to Dutch cartographer Johannes Vingboons, discovered decades after Yonge published his work, lends credence to Yonge’s theory that the then deepest part of the channel may (as George Percy wrote it was) have been very close to Jamestown Island. The Vingboons atlas, discovered in 1932, is a map of Virginia that also includes a nautical map of the James River.15 Of the location of the Colony and its proximity to the deepest fathoms Vingboons mapped in the James, “The depth off Jamestown is steady at 5 up to a small point projecting to the southeast of the three houses signifying the town, in accordance with George Percy’s assertion that “our shippes doe lie so neere the shoare that they are moored to the Trees in six fathom water.” … That the soundings end at Jamestown indicates that ocean-going ships requiring a draft of fifteen feet or more did not venture farther upriver,” (Jarvis 1997, 383). “Besides its role as a finding aid, the Vingboons chart also helps to confirm the tentative identification of the location of the first Jamestown site” (Jarvis 1997, 389). In fact, in 1994, confirmed by dates of early 17th century palisade post holes, fort features, and more than 15,000 late Tudor and early Stuart artifacts discovered there, archaeologist William Kelso located the first Jamestown Fort on Jamestown Island (Jarvis 1997, 390-392). It is just where Yonge speculated in 1903 it would be. If indeed the island’s proximity to the depth in the James necessary for the draft of a seafaring vessel was close by Jamestown Island’s shore, Yonge may not have been wrong to consider that early Jamestown sites may still exist in the James. They might have been waterfront features.

As of the mid 1990’s, three projects attempted to locate “potential offshore components of historic land sites [sic. which] all concern well-known seventeenth-century settlements on the northern bank of the James River” (Blanton 1994, 58). Said another way, archaeologists looked for possible offshore sites along historic Jamestown. Any of these studies could have located remnants of a Jamestown waterfront or pier. The first sought indications of the then still not yet discovered early Jamestown fort, and occurred in the mid-1950’s before modern underwater archaeological theory existed. Their methodology was to attempt, “fixed-interval testing using a power-operated clam shell bucket [sic. which] resulted in 65 random “drops,” or uncontrolled scoops, the locations of which were plotted from shore-based transits. … seventeenth-century artifacts were recovered in 19 of the drops, almost all within 200 ft. of the [sic. modern protective Jamestown site] seawall” (Blanton 1994, 58). It is worth noting that 200 ft. from the colonial Jamestown shore is also the measurement at which Yonge estimated, based on his investigation, deep water would have existed, in the 17th century, off a point of land extending from the island (Yonge 1904, 273). The second study, in 1978, tried to find colonial Wolstenholme Towne on the James by excavating test pits perpendicular to the shoreline but not many artifacts were found. What was discovered based on the geology of the site was, not unlike Jamestown Island, at the possible Wolstenholme site “… the approximate contours of a pre-existing promontory that may have extended 100 yd. or more into the river in the early 1600s” (Blanton 1994, 58). In 1992, the third archaeological offshore study “… used side-scan sonar to examine the shallows off Jamestown Island and detected a rectilinear anomaly that, the team speculated, might represent the outline of a bastion, building, or foundation. Attempts to verify the target through firsthand examination some months later proved inconclusive” (Blanton 1994, 58). Though not found after a second look, a third attempt to find a potential rectangular shaped object off the Jamestown Island, in the river, would be worthwhile. Successful underwater archaeological investigations conducted elsewhere, as the studies discussed below demonstrate, locating or determining what a possible historical site or feature is may require more than one attempt to confirm its existence.

The most recent underwater archaeological investigation was carried out in 2006. It was conducted by “…underwater archaeologists Steve

Photo Credit J Carpenter 2007.

If Bilicki did indeed locate an early Jamestown ship landing site, it is important to keep in mind this is the first known discovery of archaeological evidence of maritime commerce during the early Colony, but more importantly it remains visible at the shore, today, at low tide – indicating that Yonge could be right about there having been little erosion along the James River’s edges or shore (Yonge 1904, 271).

With regard to underwater archaeology across the entire Virginia Commonwealth, the Report states, “Apart from these few examples, most of the underwater archaeological activity undertaken in Virginia has involved the search for or investigation of shipwrecks associated with the Revolutionary and Civil wars. The state’s best known and largest concentration of significant underwater sites lies in the York River near Yorktown …” (Blanton 1994, 58). To be clear, this largest concentration of sites, in the York, is not arrived at by comparison – for there are no other underwater sites that have been investigated in Virginia to the degree those in the York River have been.

If conducted today, could an archaeological investigation even find anything of an English 1607-era wooden pier or later waterfront, in the James, if it had once existed? Yes.

On July 19, 1545, during the Battle of Solent the Mary Rose, King Henry VIII’s “… fully-fitted, heavily armed warship carrying over 400 sailors, soldiers and gunners” sank amid a naval battle with the French Fleet.”18 Fewer than 40 men survived. She went down in the Solent, the body of saltwater between Portsmouth, United Kingdom, in the south of England, and the eastern end of the Isle of Wight, in the English Channel. Salvage attempts were made in the months following her sinking but she was not seen again until 1836 by a diver hired to untangle fishing nets below the surface. Among other things, this sighting confirmed, at least in 1836, that she was not just still visible, but indeed, the Mary Rose still existed. This account caught the attention of a 20th century historian. After searching underwater in the Solent for six years, in 1966 Alexander McKee, “… found that there was no ship to be seen. Instead the seabed comprised a soft mud with ‘occasional eroded lumps of clay upstanding from it, beds of slipper limpet shells in layer-lines as if sorted by wave action, and now and then, quite wide pools of sand …” but based on the 1836 description of the ship’s location, sonar was brought in and sonar confirmed that, though nothing of it was visible on the ocean floor, he had indeed located the Mary Rose (Marsden 2003, 31-32). During 1969 and 1971, using water jets, a crane-grab dredger, and probes, he and his team excavated to determine if the Mary Rose’s superstructure still existed under the surface of the seabed. Nothing was found until the 1970 field season when a student, probing a trench excavated to locate the ship, exposed a plank. Treenail holes in the plank, the very type of nail used in ships’ construction during Henry VIII’s reign, revealed where it had once been attached to a ship’s frame, confirming Mary Rose’s remains indeed still existed (Marsden 2003, 33-34). It took four years and many attempts to confirm a reasonably developed theory about the location of an underwater historical site made of wood that was by then 425 year old – and they succeeded. Not unlike the geology of the James River’s riverbed, “The ship lay in soft yielding Eocene clays that allowed it to sink into the seabed, assisted by the scouring action of the tides below the surface” (Marsden 2003, 71). By the end of the excavation, recovery, and preservation effort, no less than a majority of the wooden ship and an impressive amount of artifacts were recovered from a fully submerged and buried site, of a vessel that was, on the day she sank, 62 years older than Jamestown. The Mary Rose is now a world famous museum and tourist stop where visitors can see the reconstructed original vessel, and even learn about her crew from the archaeological investigation of the site, including where specific individuals were standing on the ship when she went down, and what their roles were.19

In fresh water, in the Thames River in London, a stone quay (a landing place built parallel to the water’s edge) of the East Watergate near Blackfriars, dating from the 14th century, originally fully submerged was excavated in 1973, in part revealing at least three complete and intact oak rubbing posts, attached to the quay to protect moored vessels’ hulls, which were in such good condition that they were hauled off, stolen, after excavation.20 In the same year, during another excavation in the Thames, at the Old Custom House site, also complete and intact “… a late twelfth century clinker-built boat …” was discovered as it had been reused to construct the inboard face of a late 13th or 14th century waterfront on the Thames (Marsden, 1996, 41). The first of these complete wooden Thames River finds, as dated, was not quite 600 years old. The second, was a nearly 800 year old wooden feature, and intact. These two are not nearly all of the wooden underwater antiquities discovered nearly whole or intact, of hundreds of years of age, some older than Jamestown, within the English Channel, United Kingdom or the Thames, or elsewhere in the world.21

What pier or dock or other waterfront feature might have existed in the first three decades of Jamestown that an archaeologist could investigate today?

Records indicate that during the medieval era in the port of London “wine arriving … from France was either hoisted out of the ship berthed at the quay … or if the ship was moored in the stream … had to offload into a boat which took the barrels of wine ashore … Once on the quayside the barrels were rolled into cellars, which at the Vintry in London were by the waterfront …” (Marsden 1996, 40). At Billingsgate, also on the Thames, the very early (11th – 12th century at least) “part of the waterfront took the form of a sloping artificial beach, possibly for vessels to run ashore. There were also timber revetments and a man-made inlet or dock for a small boat. But by the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries much of the waterfront of London comprised timber and stone quays, in which parts of broken-up ships and boats were sometimes reused.” (Marsden 1996, 40). These are features dating to hundreds of years before the founding of Jamestown in 1607, to be sure. Too, as in the English medieval era, Stuart mariners sailed out of many ports, and not just London. So, the technological know-how brought to Jamestown during its first decades was likely representative of the structure and building practices from a variety of places, not just knowledge from London port. Having said this, it is reasonable to try to understand what any English port’s processes and edifices were for the movement of cargo and mooring of ships and boats, that apparently traded in shipping commerce in the same volume (or similar usage of port type facilities) or that served a population size similar to that of the early Jamestown Colony. Though Jamestown, it is understood during its first three decades, due to injury, disease, starvation, and warfare, had a waning, generally smaller population, a case might be made that 1607 Jamestown and in the decades after, at least its volume of trade from the water was not dissimilar to that of medieval London port.

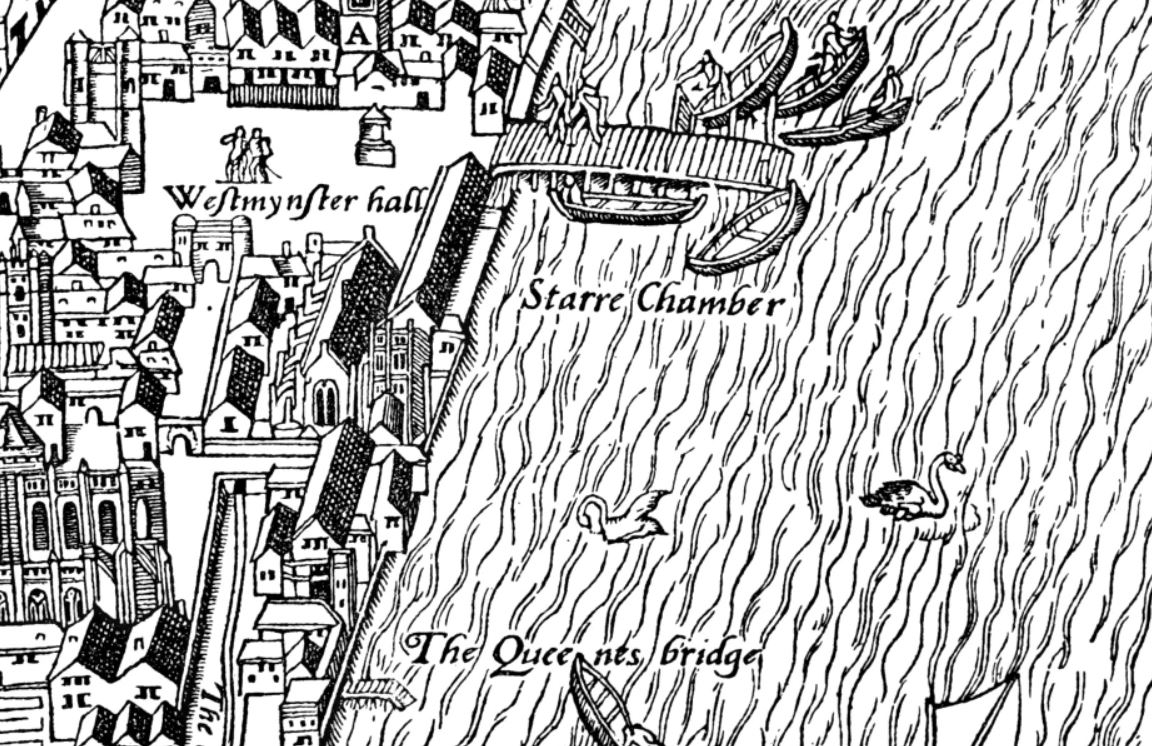

highlighted Three Cranes near Queenhithe in the Vintry Warde London mid 16th – early 17th c – portion of the The Agas Map of London 1561 to 1633

As for waterfront features typical of the years during Jamestown, the Agas Map of London, which it is believed today, fairly accurately depicts each of London’s buildings, also portrays the Thames River, ships, boats and the infrastructure for embarkation, the movement of cargo, and mooring. The Agas Map is dated (in its published variations) from its first edition in 1561 to 1633. It is helpful because comparatively the Agas Map depicts waterfront infrastructure, being used in London, during Jamestown. The Agas Map’s detailed depictions of piers, docks, and wooden cranes then used may be similar to any of these structures used in other English waterfronts of that time (i.e. Jamestown), and could exist in and along the James, today. For example, as Yonge proposed, the early Jamestown construction referred to in historical records as a ‘bridge’ being built to assist with unloading ships at Jamestown was more likely a late Tudor or early Stuart term then used for what we call a pier or dock, today. His theory seemingly bears out here, too, as at least two different docks, in the Agas Map, are individually called ‘bridge’ but are clearly depicted and appear to be docks (or piers).22

The Court’s and The Privy [Council’s] Bridges, London mid 16th – early 17th c – portion of the The Agas Map of London 1561 to 1633

Queens bridge, Westminster Hall Star Chamber in London mid 16th – early 17th c – portion of the The Agas Map of London 1561 to 1633

Unfortunately, at least as of the date of the Virginia Underwater Archaeology Report, the future of underwater archaeology within the Commonwealth did not look promising. “With the termination of the DHR’s [sic. Department of Historic Resources] nautical unit and in the absence of funding for underwater projects more generally, little work other than “Section 106,” or government mandated cultural resource management (CRM), surveys has been conducted since the late 1980’s” (Blanton 1994, 62).23

“In fact, no body of water in the state, including the York River, can be said to have been surveyed systematically and comprehensively. The virtual absence of archaeologically confirmed wreck sites in those portions of the Chesapeake Bay and Atlantic Ocean that lie in Virginia waters attests to the reality that little survey work has been conducted in these areas; that historical data have not been applied to them; and that informants, specifically watermen, are not providing DHR with the benefit of their knowledge concerning site locations. … Without field examination, which was beyond the scope of this project,[sic. Report], their assessment must necessarily be general in scope …” (Blanton 1994, 82). In the final chapter of the Report, “Chapter 6: Recommendations for Management of Underwater Cultural Resources” under “Historic Priorities”, among other recommendations, it says “A fundamental goal should be to preserve a representative sample of the various site types for each of the designated temporal periods” (Blanton 1994, 91, 93, 95).

That early Jamestown colonial shipping industry, construction, and infrastructure like waterfront or wharf features may exist in or along the James today is possible. Bilicki’s findings during his 2006 general survey of Jamestown island’s surrounding waters is a start. Given what little archaeological research has been done along and in the James, historians are left to make general statements about the maritime uses of these colonial sites. The discovery and study of among the earliest English colonial shipping and commerce, ever, in America, would begin to provide answers to questions historians have long asked, as the archaeological work on colonial Fort George in Popham Colony, Maine or colonial English Newfoundland is doing. That Jamestown discoveries would be made is likely. What we would learn from those discoveries would help us better understand this first permanent English port in America.

© 2020 Arlene Spencer. All Rights Reserved.

- Simmons, Parker P. 1907. American History Leaflets Edited by Albert Bushnell Hart and Edward Channing. The Founding of Jamestown by George Percy. Harvard University, No. 36: 10.

- Elizabethan Merchant Ships and Shipbuilding, Dr Ian Friel, FSA, Presentation Tuesday, 29 September 2009, at Museum of London, Gresham College, pg. 6.

- Pope, Peter. “Historical Archaeology and the Demand for Alcohol in 17th Century Newfoundland.” Acadiensis 19, no. 1 (1989): 72-90. Accessed February 5, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/30303065.

- Tabor, William H. 2002. “Maine’s Popham Colony”. Athena Review Journal of Archaeology, History, and Exploration 3, No. 2. http://www.athenapub.com/AR/10popham.htm. Visited January 18, 2020.

- National Register Bulletin. 1995. How to Apply The National Register Criteria for Nomination. U.S. Department of the Interior. National Parks. Cultural Resources: 2. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalregister/upload/NRB-15_web508.pdf. Accessed January 28, 2020.

- Kingsbury, Susan M. 1905. An Introduction to the Records of The Virginia Company of London. Washington. Government Printing Office, 12.

- Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 1911. Minutes of the Council and General Court, 1622-1624, Henry Read McIlwaine, Editor. Vol. XIX, No. 2, April: 136 – 137.

- Kingsbury, Susan Myra. 1906. Records of the Virginia Company of London, Vol. II. Washington, Government Printing Office: 121, 231, 174–182, 449, 496.

- Theodore W. Allen’s The Invention of the White Race, Volume II, (2012) is recommended reading about the English experience of servitude in Virginia and how English servitude led to the African slave trade and slavery in America.

- Blanton, Dennis B. and Samuel G. Margolin. 1994. Department of Historic Resources Survey and Planning Report. An Assessment of Virginia’s Underwater Cultural Resources Virginia. Williamsburg, No. 3: 2, Appendix A: Historic: 1, 6, North Coastal Plain: 4.

- Two of the three 1607-1750 underwater James River archaeological sites are listed as “piers” and one as “undetermined” any of which may be associated with the settlement of the Colony, but none of which, because of the 150 year date range, specifically indicates for early Jamestown (Blanton 1994, Appendix A: North Coastal Plain: 4).

- Jamestown Rediscovery. Archaeology. Excavations and Research. https://historicjamestowne.org/archaeology/projects/. As of February 15, 2020.

- Fenske, Kelsey. 2016. “History Influencing History: Changing Perceptions of the Starving Time at Jamestown.” PhD diss., College of William and Mary.

- Yonge, Samuel H. 1904. “The Site of Old “James Towne,” 1607-1698.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 11, No. 3 (Jan.): 257-276.

- Jarvis, Michael and Jeroen van Driel. 1997. “The Vingboons Chart of the James River, Virginia, circa 1617.” The William and Mary Quarterly 54, No. 2: 380.

- Carpenter, Jodi. The Museum of Underwater Archaeology. The Jamestown Island Submerged Resources Survey by Jodi Carpenter. https://mua.apps.uri.edu/in_the_field/jc.html. Last visited February 1, 2020.

- Carpenter, Jodi. 2007. ‘Glimpsing Beneath the Waters: A Survey of Jamestown Island’s Submerged Resources.’ Maritime Archaeological and History Society. MAHS News (18) 1:3.

- Marsden, Peter. 2003. Sealed By Time The Archaeology of the Mary Rose Volume I. Portsmouth, The Mary Rose Trust Ltd. xii.

- The Mary Rose Trust. The Mary Rose. Archaeology and The Mary Rose. Portsmouth. https://maryrose.org/archaeology/. Visited February 1, 2020.

- Marsden, Peter. 1996. Ships of the Port of London Twelfth to Seventeenth Century AD. London. English Heritage, 40.

- For instance, see The Vasa which sank on her maiden voyage in Stockholm, in 1628. Vasa Museum. https://www.vasamuseet.se/en. Visited February 5, 2020.

- The Queen’s Bridge and The Privy Bridge. The Agas Map. The Agas Map of Early Modern London. https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/agas.htm Jenstad, Janelle. The Agas Map. The Map of Early Modern London. Ed. Janelle Jenstad. Victoria: University of Victoria. https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/agas.htm. Visited February 2, 2020.

- In the U.S., Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act is the law, here referenced, and requires federal agencies to investigate federal project sites for artifacts that may indicate an archaeological site is present. If one is found, the law requires that the lead public agency, before it may be covered or destroyed, consider what if any impact the project will have on the site and with federally recognized stakeholders, such as the federally recognized Native American Tribes, address what can be done to impact it as little as possible, if anything. Cultural Resource Management is the federal or public agency management of archaeological sites (or resources) usually discovered, during Section 106 work and similar compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). A Cultural Resource Manager is a professional archaeologist who conducts Section 106 and NEPA compliance work.