Lou Roper teaches History at SUNY—New Paltz, which is located near the Hudson River midway between New York City and Albany. A specialist on early modern England and its empire, he is the author of three monographs, including most recently Advancing Empire: English Interests and Overseas Expansion, 1613-1688 (Cambridge UP, 2017), and the co-editor of five volumes of essays, including most recently Agents of European overseas empires: Private colonisers, 1450-1800 (with Elodie Peyrol-Kleiber, Agnès Delahaye, and Bertrand Van Ruymbeke, Manchester UP, 2024). His most recent article, ‘Reorienting the “origins debate”: Anglo-American trafficking in enslaved people c. 1615-1660’, appeared in Atlantic Studies last year.

I’m afraid I couldn’t resist the temptation to respond to the invitation from the GMH editors to historians to talk about their new/forthcoming work on their site. By happy coincidence, their notice arrived between publication last March of a volume of essays I co-edited with Elodie Peyrol-Kleiber, Agnès Delayhaye, and Bertrand Van Ruymbeke on ‘private’ agents of empire published by Manchester University Press and the submission of another manuscript of essays that I am co-editing with Joseph Wagner to Amsterdam University Press on the subject of colonising failures.

The Manchester volume includes treatments of the careers of these agents in contexts that include Dutch trafficking of enslaved Africans to New Netherland, the historiography of ‘settler-colonialism’, the inter-colonial commerce in mules, and migration to sixteenth-century Spanish America. The Amsterdam volume includes cases ranging from New Sweden to the moribund Danish attempt in Guinea to early efforts to colonize the Bahamas.1

The Guinea Company

My ‘contributions’ derive from my continuing interest in seventeenth-century (especially prior to 1672) English overseas interests and naturally builds upon prior work that confirmed the centrality of the traffic in enslaved Africans to those interests. Led by the former indentured servant Maurice Thompson who also oversaw the first English slaving voyage to an English colony (St Christopher) in 1626, the ‘engine room’ here provisioned colonies, pursued trade with Native American societies, and became involved in the ‘Guinea trade’ during the 1630s before assuming control of the Guinea Company in the mid-1640s.

This group pursued the uniquely ambitious global vision of the Anglo-Dutch merchant Sir William Courteen that they had inherited. This ‘national settlement’ of English overseas interests, as they termed it, sought to link Indian Ocean commerce—and, ideally, China, Japan, and even Pacific Coast of America—to Courteen’s Caribbean operations with the ‘Guinea trade’ as the linchpin. Accordingly, Indian fabrics (and saltpetre) would be exchanged for African gold; those fabrics, along with European commodities, such as Swedish iron, would be traded for enslaved people and ‘elephants teeth’; and enslaved people, along with other ‘supplies’, exchanged in America for tobacco, sugar, and other plantation commodities.2

The execution of this had the most profound geopolitical consequences. The Guinea Company and their associates prodded the English Republic to pass a Navigation Act (1651) against ‘interlopers’ on their patch and then to pursue war (1652) against their fierce Dutch rivals; demonstrations of how ‘mercantilism’ looked in the mid-seventeenth century. The sudden ‘restoration’ of Charles II in 1660, though, curbed their supremacy in overseas matters as it forced a merger between the group and the king’s brother, James, duke of York, who, with his cousin Prince Rupert and others in his network, had a keen interest in the traffic in enslaved Africans and imperial affairs. The new partnership, though, seamlessly continued the anti-Dutch policy of the 1650s.

English Trafficking of Enslaved Africans and Santa Cruz

The global significance of the competition between the Guinea Company and the Dutch is particularly manifest in the company’s promotion of the ‘Western Design’ (1654-55) against Spanish interests in the Caribbean. This endeavour married the company’s longstanding desire to increase the volume of its commerce in enslaved Africans and other commodities to Habsburg America with the Cromwellian view of the Spanish monarchy as ‘Antichrist’. This conjunction was enabled by the friendship that quickly developed between the government of Felipe IV and the Dutch Republic after their eighty years of war ended in 1648.

In addition to trafficking enslaved Africans to places such as modern Venezuela, the Guinea Company also moved to establish a colony on the island of Santa Cruz (modern St Croix) in 1649 after the execution of Charles I brought its political allies into the ascendancy. This colony is the subject of my essay in the volume for Amsterdam UP cited above.

Santa Cruz proved to be the only direct involvement of the Guinea Company collective in American colonization although they attempted a corresponding one at island of Assada (‘St Lawrence’, as the English called it) near Madagascar as part of an intended chain of operations that was to stretch from Run in the Spice Islands to Barbados. The Indian Ocean venture almost immediately ran afoul of Native hostility (as the attempt to takeover Run crashed in the face of Dutch ‘insolence’).

A topographicall description and admeasurement of the yland of Barbados in the West Indyaes : with the mrs. names of the seureall plantacons: https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:4m90fk45d

Meanwhile, their Caribbean effort (not to be confused with earlier attempts at Santa Cruz) sank with scarcely a trace. The activities of the Guinea Company have largely escaped historiographical attention since they tended not to generate a record found in the sources customarily consulted for colonial and maritime history and the papers generated by their membership—if they ever existed—have disappeared.

Rather, as in the case of the hitherto unknown Santa Cruz venture, tracking the history of this group requires trawling through the uncatalogued and largely unfoliated records of the High Court of Admiralty (HCA) held at The National Archives at Kew/ Last year Graham Moore contributed an excellent blog post on this Aladdin’s Cave to GlobalMaritimeHistory.

Within this mass of evidence we have depositions that reveal that on 27 June 1649, the Guinea Company freighted the 160-ton Jonathan (Robert Harding, master) for a voyage ‘to Santa Cruz in the West Indies from where ‘she was ordered to sail to Guinea and so to Barbados where she was to take in her lading of sugars & indicoes & what other good commodities the said island afforded & so from there was and is to return to this port.’

On board were ‘chief planter’ and supercargo for the company’s goods, Robert Masters, who was to oversee ‘the erection of the said plantation’, and John Barker who had charge of the independent interests of John Wood, a Guinea Company principal, and at least ‘40 servants which were intended for the plantation at Santa Cruz.’ The ship also carried goods worth £1,100. According to Harding, ‘the furnishings of the ship for the voyage in question and the hire of the servants for the colony and the provision and of victuals did come besides the freight cost’ totalled £4700. Harding stayed at Santa Cruz for three months ‘to give his advice’ before departing for Guinea on 11 December 1649 in order to acquire enslaved Africans for the colony.

It bears noting that Wood had as much knowledge of sub-Saharan Africa as any English person in 1649 did having been involved in—and travelled to—that place for almost two decades by the time of the freighting of Jonathan. He was also, as the note above reflects, a close associate of Maurice Thompson and the other Guinea Company leaders.

Accordingly, after depositing the English servants (at least three of whom died in the crossing) and planters at Santa Cruz, the Jonathan made its way to Cormontine on the Gold Coast in modern Ghana, which had become the centre of English involvement in sub-Saharan Africa after its acquisition in 1632. He spent over six months there during which time he acquired 187 Africans, apparently in accordance with the ability of the company’s factors to acquire them. The enslaved people who were boarded in, say, March had to wait in confinement until the Guinea Company operatives secured enough ‘commodities’ to make the voyage a profitable one; five enslaved people died before the ship left the Gold Coast.3

The ‘Western Design’ and Santa Cruz/St Croix

It is the price commanded for ‘Negroes’ at Barbados circa 1650, of course, that constituted the foundation of the Guinea Company’s plans. The conduct of the Guinea trade at this time makes it difficult to pinpoint its lucrativeness. In the first instance, as noted above, the factors at Cormontine engaged in the actual trading with African merchants; ships such as the Jonathan brought the goods that African partners wanted—cloth, manillas (copper bracelets), iron bars, ‘strong waters’—and conveyed the commodities, including human beings, that the English acquired in exchange. These traders would have kept records of their activities, but none have been found dating from this period. Harding, amidst the fallout from the failure, testified in court that ‘every Negro’ was worth 1,000 pounds of sugar per head or £12 10s at Barbados although the experienced mariner Robert Bell claimed that the going rate for enslaved Africans there was £15 sterling there.4

A chronological extrapolation, moreover, sheds some light on the substantial profits involved aside from the reality that the number of participants in the trade speaks to its attractiveness in and of itself: slaving voyages from the early 1660s for which we have accounts indicate that these endeavours brought between £17-20 sterling per enslaved person to traffickers. Even the figures cited in the Jonathan case—possibly exaggerated or affected by Dutch competition or piracy—would have brought approximately £10-12 per human being.5

Having seen their wider plan frustrated, the Guinea Company maintained their hopes for cornering the traffic in enslaved Africans in Spanish America. A vacuum had been created in this lucrative commerce when Portuguese control of it was terminated by the outbreak of the rebellion against the Habsburg monarchy at the end of 1640. In conjunction with the new friendship between the government of Philip IV, which Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of England after 1653, regarded as ‘Antichrist’, and the Dutch Republic after the end of their eighty years of war in 1648, the company leadership successfully promoted the idea of a ‘Western Design’ to the new Protectorate.

The aim of this unprecedented English attack on foreign interests outside of Europe was clearly the supply of enslaved Africans to Spanish colonies: the proposed targets were Santo Domingo, long a location for illicit English trading; Cartagena, the central market for the importation of enslaved Africans into Spanish America; and Puerto Rico, another ‘peripheral’ colony but, perhaps not coincidentally, the location from which the Spanish had put paid to the Santa Cruz colony—was revenge in the mix here?

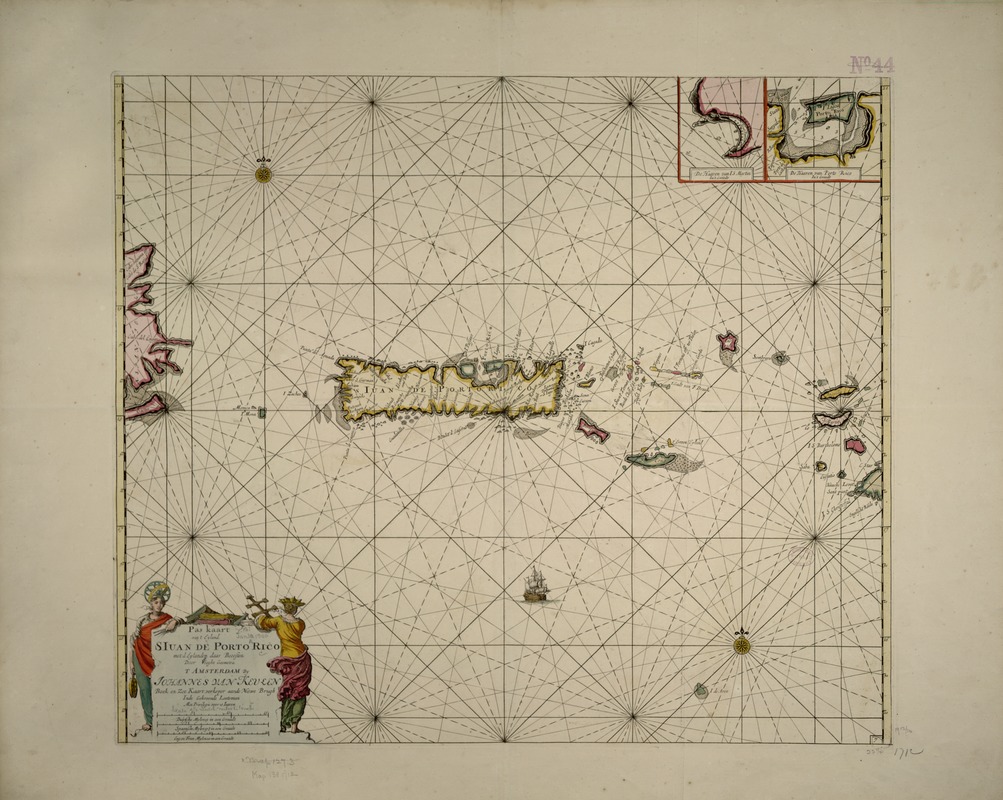

Pas kaart van t eyland S. Iuan de Porto Rico, met d eylanden daar beoosten, https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:x633f921x

Regardless, the Design’s attempt at Santo Domingo failed surprisingly and dismally. The situation, though, was recovered by an improvisational attack on Jamaica; the securing of this western Caribbean base suitable both for plantation agriculture and trade with the Spaniard, both dependent on trafficking enslaved Africans, was finally confirmed in 1662 and it duly became the most important British (after the Union of 1707) colony in the eighteenth century.

REFERENCES

- ‘Global pursuits: English overseas initiatives of the long seventeenth century in perspective’ in ed. Elodie Peyrol-Kleiber, Agnès Delahaye-Dado, L.H. Roper and Bertrand Van Ruymbeke, Agents of European overseas empires: Private colonisers, 1450-1850 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2024), 66-87; and ‘Snatching Imperial Success from Spectacular Colonizing Failure: The Case of the English Attempt at Santa Cruz (St Croix), 1642-1660’ in ed. Joseph Wagner and L.H. Roper, European Colonial Failures, c. 1560-1800: Early Modern Polities, Overseas Interests, and Empire Building (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, forthcoming).

- The National Archives of Great Britain, CO 77/7, Papers of ye Merchants trading to Assada giving reasons why they refuse to join with the East India Company in a 5-year voyage upon the old joint stock, f. 66, 10/21 November 1649 in accordance with the Julian calendar then in effect in the Anglophone world.

- The National Archives of Great Britain, Kew, HCA 13/124, Personal answer of Robert Harding to Rowland Wilson, Maurice Thompson, John Wood and Company, 27 March 1652, unfoliated.

- The National Archives of Great Britain, Kew, HCA 13/124, Personal answer of Robert Harding to Rowland Wilson, Maurice Thompson, John Wood and Company, 27 March 1652; HCA 13/65, Deposition of Robert Bell in Rowland Wilson, Maurice Thompson and Company of Adventurers to the Gold Coast v Robert Harding, 3 May 1652, unfoliated.

- For accounts from 1662, National Archives of Great Britain, Kew, T 70/309, ff. 5r, 8r. For goods involved in the Guinea trade at this time, National Archives of Great Britan, Kew, HCA 13/62, Deposition of William Jacket, 6 March 1649/50, unfoliated.