Thank you to Dr Peter Cole for this museum gallery review of ‘Europe and the Sea’. Peter Cole is a professor of history at Western Illinois University. He wrote Wobblies on the Waterfront: Interracial Unionism in Progressive-Era Philadelphia. His next book, Dockworker Power: Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area comes out in December 2018. He can be found on Twitter as @ProfPeterCole.

The Berlin-based German Historical Museum (Deutches Historiches Museum), the country’s national historical museum, currently has a very impressive show that any and every maritime historian would appreciate. This exhibit covers several thousand years of history along with a vast array of themes broadly connecting Europe and the (maritime) world. The effort at “thinking big” is commendable. It goes without saying, given the massive sweep of time, space, and theme, that a great many subjects are not covered or could be more fully explored. However, that should not deter anyone from attending if in Berlin in the next few months.

Pierre Bontier and Jean le Verrier, chronicle: Conquête et les Conquérants des Iles Canaries (The conquest and the conquerors of the Canary Islands), c. 1405 © The British Library Board, Egerton 2709, f.2.

Exhibition curators Dorlis Blume, Christiana Brennecke, Ursula Breymayer and Thomas Eisentraut center the sea in their examination of two thousand years of European history. To some people, this approach might seem counterintuitive though, no doubt, maritime historians need no convincing of the sea’s tremendous import. The curators divide up the subject into more than a dozen different sections that feature individual port cities in order to highlight specific themes and eras.

Their approach is most logical as port cities always have been the obvious, and very real, connection between land and sea. People, information, and goods circulate via port cities. They drive economies. They are places of excitement, creativity, and cultural exchange. Port cities are where knowledge of all sorts—cultural, geographic, nautical, political, religious, and so on—is exchanged. So, too, news from distant lands. Generally, they are where change happens and new trends emerge. They are, to use a modern word that equally applies to ancient times, cosmopolitan—as peoples from many different cultures interact and, accordingly, change the inhabitants of said port cities.

Head of Odysseus, copy of a Hellenistic original, c. 250 A.D. © Kunst- und Kulturzentrum (KuK) der StädteRegion Aachen, Monschau

Athens (and its port Piraeus) are the predictable, and appropriate, place to begin a survey of the intersection of European and maritime history. Before exploring Athens, however, viewers first confront a small statue titled, “Europa on the bull” (c. 500-BCE). This artifact tells the ancient Greece myth that bequeathed to the continent its very name. It also is, seen in a feminist manner, about how the god Zeus abducted and raped a woman, Europa. It may seem a curious place to start though the story has roots among the seafaring Phoenicians and the Mediterranean island of Crete.

From Athens, the exhibit travels through the Mediterranean and Ionian Seas and up the Adriatic all the way to Venice, the great and legendary city-state. In the first centuries of the second millennium, this city of islands dominated trade amongst the European, Mediterranean and Asian worlds. The section highlights how Venice came to control an empire from southern Europe and northern Africa, through the Levant, and into the Black Sea. One painting explores its Arsenal, a city-owned complex of shipyards that pioneered mass production techniques commonly much more associated with the rise of industrial production.

The exhibit does not focus much on naval history. The most extensive treatment is the pivotal Battle of Lepanto. In 1571, a fleet of the so-called Holy League—with Venetians at the helm—engaged in a massive naval battle against an Ottoman navy. The combined forces of Venice, Spain, and other Catholic European powers defeated the Ottomans. The exhibit provides the standard explanation of the battle as seen through the lens of religion; that is, with Europe seen as Christian (though already divided between Catholic and Protestants) and the Ottomans as Muslim “infidels.” Of course, there was a long-standing presence of Muslims in various parts of Europe, including what now is Spain and throughout the Balkans.

View of Seville, c. 1600, unknown Spanish artist © Museo Nacional del Prado

Seville, in Andalusia, was the Spanish empire’s first great port city. For a while, Seville served as the exclusive entrepot for all ships representing the Castilian royalty (and, today, houses the Spanish colonial archives, Archivo General de Indias). A wonderful 16th century painting of the port, choked with ship traffic, also makes clear how curious that this city became such an important port; after all, it is located 80km from the sea, up the Guadalquivir River—a name with Arabic origins that complicates what Lepanto supposedly represented. Seville also signifies European imperialism that began with the Portuguese and Castilian monarchies dispatching technologically sophisticated ships, starting in the 15th century, to explore (and conquer) the Atlantic world and beyond.

Interestingly, the curators chose the Canary Islands to represent the impacts of European colonialism. This group of islands is located in the Atlantic due west of modern-day Morocco. While to many people today, perhaps especially in Spain, it is considered Spanish and a lovely place to spend a holiday, the curators thoughtfully explain that it also exemplifies European imperialism. The indigenous peoples who inhabited Tenerife and the other Canary Islands fiercely resisted conquest for more than a century before succumbing to Castilian firepower and diseases.

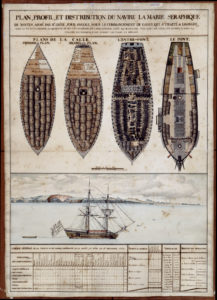

Jean-René Lhermitte, Layout, profile and transactions of the slave ship Marie-Séraphique, c. 1770 © Château des ducs de Bretagne – Musée d’histoire de Nantes

In a similar vein, the port of Nantes stands in for Europe’s centuries-long involvement in “human trafficking,” more typically called the slave trade in the United States. Along with Britain’s Liverpool and Portugal’s Lisbon, Nantes—in Brittany on France’s Atlantic coast—was France’s premier slave trading port. The exhibit highlights Le Code Noir of 1685, which established the rules of slavery and slave trade in the French empire. Subsequently, Nantes became a vital hub for African slavery. The French profited from the buying and selling African slaves as well as from its immensely profitable sugar plantations in the West Indies. So did other European empires.

These and other port cities brought in what became “essential” consumer goods to Europe including sugar, coffee, cocoa, tobacco, cotton and other fabrics, liquor, porcelain, and so on. The tremendous impact of maritime trade upon European diet and culture simply cannot be overstated.

The exhibit tackles the again-controversial matter of human migration in a fascinating and clever

Richard Fleischhut, Emigrants aboard the ocean liner Bremen II, 1909 © Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

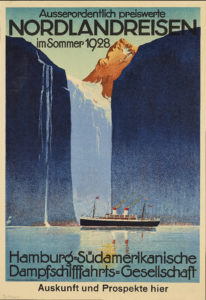

manner. Instead of focusing, first or exclusively, on the recent wave of migration into Europe from Syria, Afghanistan, Mali, and elsewhere, the exhibit focuses upon the out-migration of Germans in the 19th and early 20th centuries. A wonderful examination of the motivations and experiences of the many millions of Germans who departed from its greatest port city, Hamburg, and Bremerhaven that also exits out on Germany’s North Sea coast. Approximately ten million Germans migrated to the United States, alone, from the 17th into the early 20th centuries. This mass movement greatly impacted the US as well as their German homeland. This section also explores the current in-migration to Germany, highlighting the personal stories of five migrants, each from a different country. Other than the nations bordering Syria, Germany has taken in far more people than any other European country; upwards of 600,000 Syrians over the past four years.

Inv.-Nr:P 57/1073

The exhibit also tackles many other aspects of maritime and European history. Brighton (England), just 75km from London, represents tourism. Kiel (Germany) represents maritime research, with a sonar device used to investigate life deep underwater. And so on.

This maritime labor historian would have appreciated a greater focus upon the workers who built the ships, loaded and unloaded the ships, and sailed the ships. There are some excellent paintings of London in the 19th century where massive shipyards were constructed along the Thames River. The sailors and fish processing workers of Bergen (Norway) are featured in some wonderful photographs, as well.

The basic thesis of the exhibit is that, without the sea, Europe as Europeans now know it simply would not—could not—exist. Of course, this maritime historian agrees! For more than two thousand years, Europe has been defined by its relationship with the sea. Indeed, even today, 90% of the goods that humans (not solely Europeans) consume travel for at least part of their journey via ship.

I spent nearly two hours in this fascinating exhibit but one could spend half that time. That said, if one read every panel description (in German, “simple German,” and English), one could spend four hours. Guided tours for an four extra euros are well worth it. Mine, in English, was particularly rewarding as I was the only person on the tour!

The exhibit runs until 6 January 2019. English and German language editions of the catalog are available, too. Unfortunately, at this time there are no plans for this exhibit to travel elsewhere though I do hope that changes.