Ships’ logs are an incredible type of document for maritime historians. They are essentially ideal for modern digital humanities approaches- they are usually lengthy enough to provide some kind of good sample size, provide a mixed of types of data (numbers, text, names, etc) so they can be analyzed in a lot of different ways. On the one hand, they’re – almost dreadfully- routine. For the Royal Navy, by the 18th century- the format, the expectations were rather set. Logs were documents that were critical to the RN’s bureaucratic functioning. Lieutenants kept them, Masters kept them, and Captains kept them. And yet (and yet), there is an incredible amount of diversity in the (I’m guessing, here) thousands of ships’ logs that have been saved between the National Archives and the National Maritime Museum. I read a good many of them when I was doing my PhD- particularly when I was looking at annual celebrations related to the monarchs (it was really interesting, finding evidence that the Restoration was still specifically celebrated late in the 1740s). It would be an incredible project for ships’ logs to be transcribed, and put in to a large database that could be.. really full of interesting information. The “Colonial Registers and Royal Navy Logbooks (CORRAL) project: Meteorology Records of the Admiralty, Naval Forces, Royal Marines, Coastguard, and related bodies, volume ADM55” project certainly looks like a fascinating basis for other projects to build upon.

In this blog, I’m looking at just one blog, that of the Portland. The Portland was a 50 gun 4th-rate ship, launched in 1744 and built according to the 1741 Establishment. 1 Considering that the previous Portland was built in 1693 and broken up in 1743, this is clearly another example of a ‘rebuild’ which is in fact construction of a new ship. The documents I’ll be presenting photographs from were found at the National Archives, and are found at ADM 51/3940. This is a folder of documents, which contains several individual logs- each of which is roughly a year. (Indeed, some cover a year exactly). In this period, the Portland was commanded by Captain Charles Stevens.

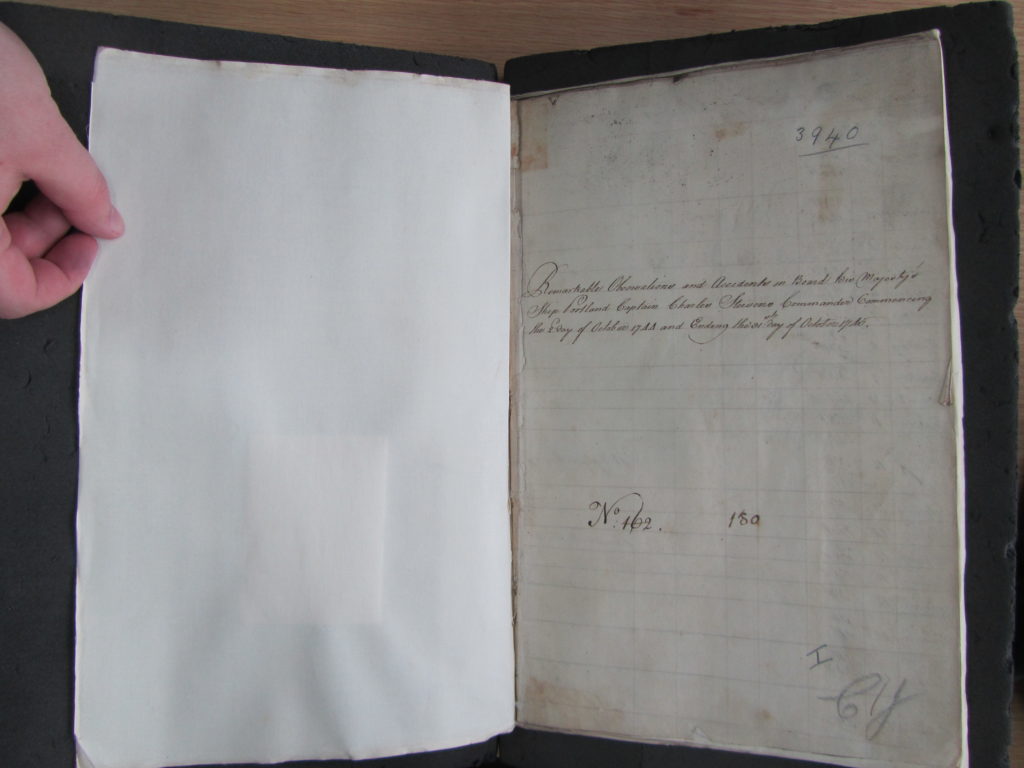

In this first example, the log covers from 6 October 1744 to 31st October 1745. NA Kew, ADM 51/3940.

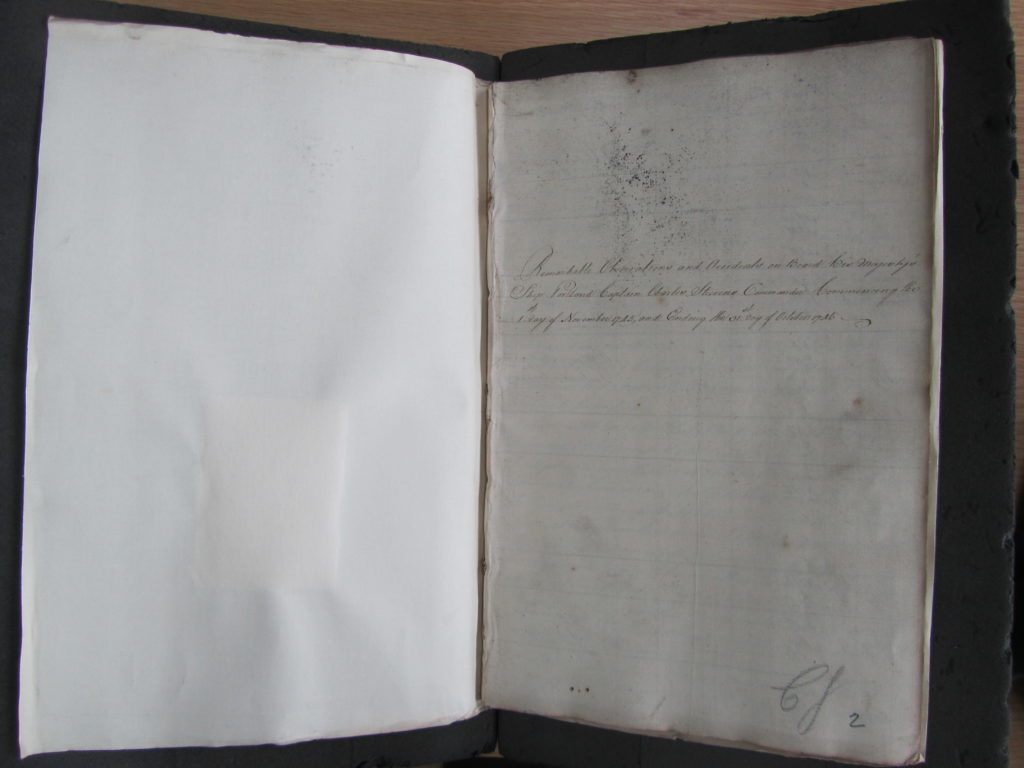

This example is the cover page of the next year’s log- which covers 1 November to 31 October 1746. NA Kew, ADM 51/3940

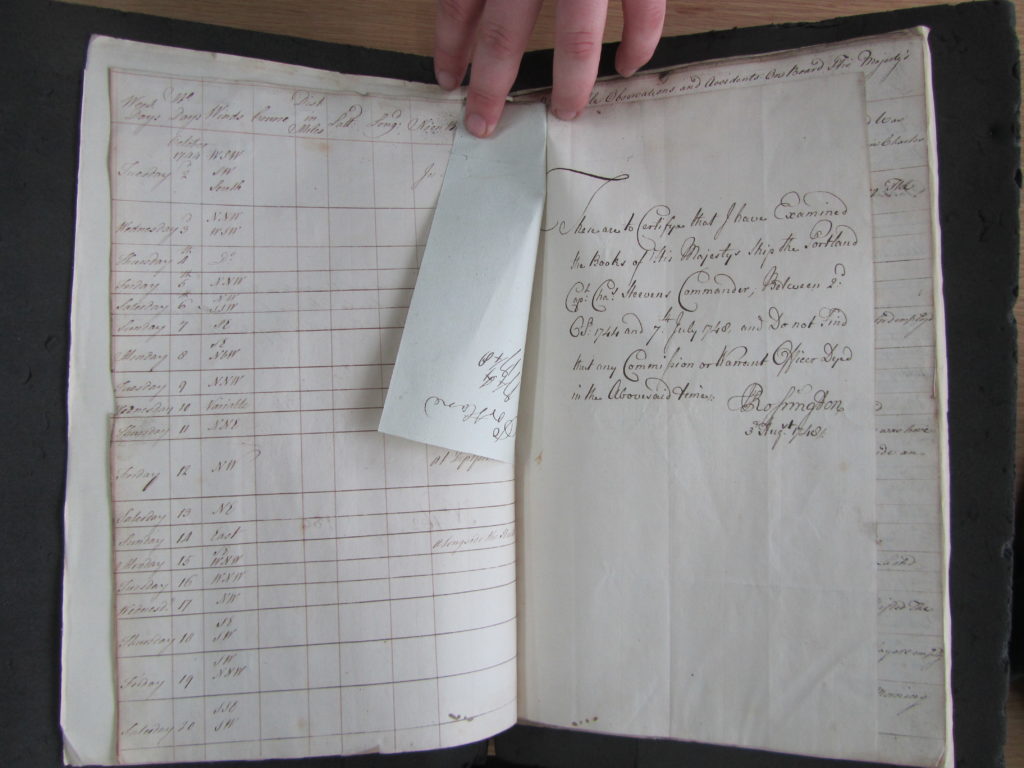

There are all kinds of fascinating things tucked into these documents. For example, here is a note from an administrator who reviewed Portland’s logs- and in this case, to certify that “and did not find that any Commission or Warrant Officer dyed in the abovesaid times”.

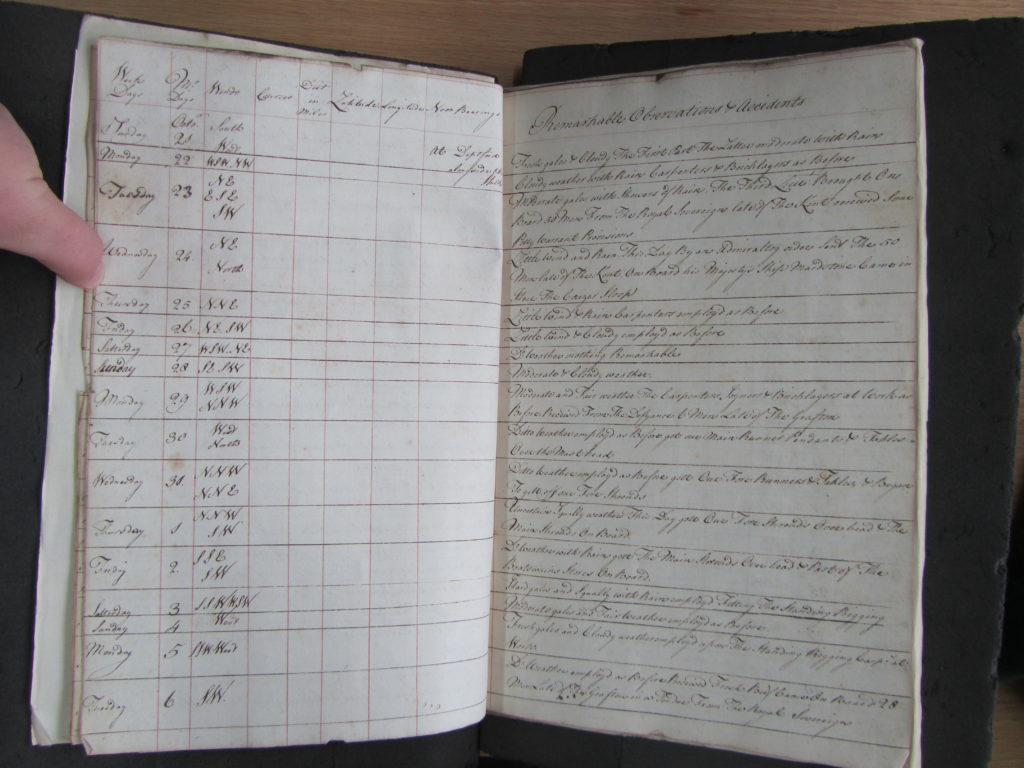

I find the way that tedium and boredom is recorded in these ships’s logs. This past summer, I spent 8 weeks aboard a Canadian Coast Guard vessel when she was in drydock. For the latter for weeks, I was the acting Quartermaster on night watch. Part of my duty was to record the weather conditions every four hours, and to record important events of my watch- in the parlance of these logs ‘remarkable observations’. For the Portland, she spent much of the first few weeks of October 1744 at Deptford, tied up to a hulk. This would certainly be a very similar situation to that which I experienced in October. In these pages, you can see that Captain Stevens is recording the details of what’s going on aboard his ship.

There are some very interesting observations here- for example on Monday the 22nd, the Captain mentions that ‘Bricklayers and Carpenters’ are continuing to work aboard the ship, and again later that week. On some days, such as the 27th, ‘nothing Remarkable’. Yet on other days, there was much happening. For example, on the 23rd, the 3rd Lieutenant brought on board the Portland 50 men (from the Royal Sovereign) who had previously served on the Kent. The next day, they moved to yet another ship- the Maidstone which had entered the harbour. The Portland was not just a temporary berth however, and was clearly making ready for sea. In the next week, efforts are being made to get the ship ready for sea. Shrouds (the standing rigging which provides side-to-side stability for the masts) were brought aboard and rigged, and various stores and provisions brought aboard. Making ready for sea took several weeks- and it was not until early 1745 that they left actually proceeded to sea.

Each time I examine a ships’ log, I am struck by how much information they contain- and their incredible potential and rich potential sources for information, for samples from which we can learn much more about the Royal Navy as a creator and possessor of information. The rise of the ‘Fiscal-military/naval state’ theory and approach to history is an incredibly important vector and one that necessarily considers military institutions as bureaucracies and very large organizations. The next step is certainly things like the brilliant and bonkers Prize Papers project. After that- however- and we’ll need some pretty advanced optical recognition software for this- is the transcription of the masses of Admiralty documents so that in addition to being digitally preserved, catalogued, and in systems that have a lot of meta data, they’ll also be text searchable. The ADM8 Project on this website is one attempt to do that, in a small way. But looking at ships’ logs, the nearly unlimited potential of such projects is clear.