Letters that the Royal Navy could not categorize as from admirals, officers, important navy boards, or other important people were sorted in “promiscuous” boxes and what they contained could vary widely, producing interesting finds for researchers. In a box of Promiscuous A letters from 1811-1813 are two anonymous letters complaining to the Admiralty about changes to the uniforms of the Royal Navy, issued in 1812.

Letters that the Royal Navy could not categorize as from admirals, officers, important navy boards, or other important people were sorted in “promiscuous” boxes and what they contained could vary widely, producing interesting finds for researchers. In a box of Promiscuous A letters from 1811-1813 are two anonymous letters complaining to the Admiralty about changes to the uniforms of the Royal Navy, issued in 1812.

Two months ago I started writing a Discuss-a-doc post about the ever-fascinating American protection passes in use before and during the War of 1812. Having written about Morris Russell’s 1813 pass, I discovered that my second document was part of a much bigger event than I had anticipated. I have since decided to lay those papers aside because they require much more work than I am able to give them at this time. Such is the way of historical research.

Instead, I thought it would be interesting to look at two letters in a single box—ADM 1/4368 or Promiscuous A, 1811 to 1813. Promiscuous boxes are fascinating because they contain the “dregs” of the Royal Navy filing system. While in-letters from naval boards, admirals, captains, and even lieutenants were sorted into their own boxes, promiscuous boxes received the letters of all the men and women who wrote to the Admiralty who did not fit into the typical institutional categories. This, as we will see, included petty and warrant officers, but also civilians. Marc Isambard Brunel’s many appeals to the Admiralty for his due payment for inventing the mass-production assembly line for the Portsmouth blocks were all placed in Promiscuous B.1 But Promiscuous A boxes are additionally interesting because, as they contained letters from writers whose surnames began with “A”, they also contain anonymous and missing letters.

Selection of a letter to George, Prince Regent, proposing changes to the uniforms of the Royal Navy, 1812. The National Archives, ADM 1/5214, March 20, 1812.

Having been directed to look at the 1811 Pro. A box, I was able to find two anonymous letters about clothing. To be specific, the letters are about the new naval uniform regulations which were introduced in 1812. In March of that year, Charles Philip Yorke, First Lord of the Admiralty, submitted to George, the Prince Regent, the list of changes for his approbation. He noted that the new regulations would take place on the Prince Regent’s birthday and that he hoped to have the orders approved in time for the officers have new uniforms made according to the new pattern. The Prince Regent approved of the changes. 2

An 1812 epaulet for captains with over three years seniority. Part of a pair, they belonged to Captain John Stockham. National Maritime Museum, UNI0098, 1812.

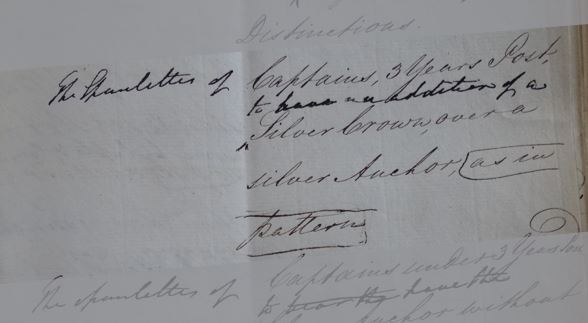

They were minor: a new uniform was devised for the Admiral of the Fleet, adding additional marks of his status like an additional row of lace on the sleeves. Captains under three years seniority and commanders were allowed full epaulets while lieutenants were distinguished by one epaulet on the right shoulder. Changes to the appearance of the captain’s epaulets were also made, adding a crown over the silver anchor of a captain with three years seniority and a silver anchor to those with less than three years seniority. 3

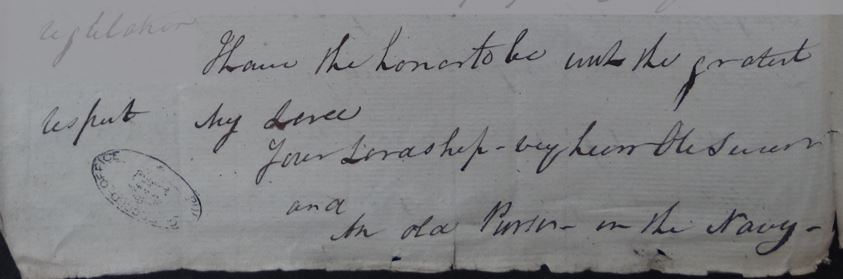

Very few changes were made to the uniforms of warrant officers, which was the subject of the two anonymous letters.4 Arriving within days of each other, the two writers almost seem to be in conversation, though at cross-purposes. First, on April 3rd, 1812, “An Old Purser in the Navy” wrote to Lord Melville, newly appointed First Lord of the Admiralty, with disappointment that no changes were made to the purser’s uniform, though “the surgeons have the distinction of an embroidered button hole on the collar.”5 He continued that,

I therefore by leave very humbly to offer my opinion to your Lordship in stating that it would be highly proper for the pursers & masters to have the first an anchor embroidered on the collar—and the latter one anchor with a small one on each side being in perfect unison with the victualing and navy office seals. Firmly believing that your Lordship will complete what your illustrious father intinded by giving the pursers the same rank as the masters and surgeons … who can now be even commanded by surgeons mates who have only been in the service a few days … I therefore venture to say that it is the most mark’d indignity to those class of officers that was ever known in any service.

The purser suggested that pursers in battleships should hold the same rank as masters and surgeons and that those in frigates and sloops should be equivalent to lieutenants. This letter was perhaps published in a newspaper or printed and publically circulated because the purser marked “made public” at the head of the letter.

The anonymous signature of the unnamed purser. The National Archives, ADM 1/4368 f. 128, April 3, 1812.

This letter brilliantly illustrates the close connection between uniform appearance and rank. The purser equated the lack of change in his uniform with the concurrent lack of change in his rank’s authority. His suggestion that masters and pursers should share a uniform distinction—the anchor embroidered on the collar—would equate them in uniform and in rank. To add a further distinction, however, the purser additionally hoped that embroidered marks from the victualling and navy office seals would be added to the collar as well. This would link pursers with their powerful administrative offices, something already an aspect of their uniforms. Pursers’ buttons were stamped with the seal of the Victualling Office, while the buttons of masters displayed the seal of the Navy Office.6

The next letter was received on April 7th. The anonymous author did not sign his name with a hint to his capacity, as the purser did, but his dissatisfaction is with the uniforms of the medical and surgical department. “Gentlemen educated to be so useful and important a profession feel concern to entering a service where they think they are looked down on,” the anonymous complainant observed.7 Both he and the purser emphasized the usefulness and responsibility of the men in the medical and logistical capacities as a reason that they should be given more authority and additional distinctions in their uniforms. The purser also reminded Melville of “the charge and responsibility of pursers—particularly in large ships.”8 The anonymous author of the second letter wanted surgeons’ coats lined with white fabric, with embroidered collars and the right to wear epaulets. “Physicians too,” he added, “epaulets as captains [and] Buttons as the other officers are to wear.”

“In the elegant improvements lately made in the Naval uniforms – no notice has been taken of the Medical & Surgical Department” wrote an anonymous correspondent to the Admiralty. This directly countered the assertion by the anonymous purser that surgeons received an embroidered buttonhole. An extant surgeon’s uniform from 1806 has such an embellishment, however, suggesting that this addition may have pre-dated 1812. The National Archives, ADM 1/4368 f. 129, April 7, 1812.

Medical officers had only received regulation uniforms in 1805, the results of an 1804 petition asking for distinction in uniform and in rank with the officers of the same class in the Army.9 Like the anonymous letter-writers above, the petitioners understood the link between distinctions in clothing and their authority within a military establishment like the Royal Navy. Indeed, naval officers had made the same appeal when they asked to be granted uniform dress in 1746, hoping to be given equivalent dress to their peers in the army. The first blue dress and undress uniforms for naval officers were issued in 1748. As Amy Miller remarks in her book on naval uniforms highlighting the collection at the National Maritime Museum, “the Admiralty was not only clarifying the role of rank and dress, but was also attempting to end the practice of dressing outside one’s station.”10

This is one of the important reasons that military dress, especially naval uniforms, are such an important subject of study: In the early modern and modern period, the dress of civilians became increasingly democratic. Men and women were able to “dress outside one’s station” or at least appear to. New fabrics entered the market like block-printed cotton and cotton blends, which imitated and even surpassed the vibrancy of silks and embroidery. New methods of manufacturing brought down the cost of cloth and also employed working women as wage-labourers, making them powerful and important consumers. In addition, ready-made clothing was gaining ground as an acceptable source of fast fashion, helped by the explosion of slop clothing required by the navy during the French Wars, making such clothes more prevalent, at least for men. However, the military worked in opposition to these civilian trends as officers, then warrant officers, then medical officers petitioned to have their authority recognized through state regulations. Contrary to trends democratizing civilian fashion, naval officers chose to relinquish their sartorial freedom t0 the government, rendering their appearance conspicuous among their non-military peers. In 1857 ratings were issued uniforms, finally completing the process of regulating naval dress begun over a century earlier.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

The National Archives, Kew: Admiralty In-letters, ADM 1, 1660-1976.

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich: Royal Navy Uniforms, Patterns 1812-1825, and 1806-1812.

Secondary Sources

Miller, Amy. Dressed to Kill: British Naval Uniform, Masculinity and Contemporary Fashions, 1748-1857. Greenwich: National Maritime Museum, 2007.

Citations

- See a March 1808 letter Brunel wrote complaining of duties on his allowance from the navy, for example. ADM 1/4380 f. 684, March 24, 1808, National Archives, Kew [TNA].

- ADM 1/5214, March 20, 1812, TNA.

- ADM 1/5214, March 20, 1812, TNA. See also Amy Miller, Dressed to Kill: British Naval Uniform, Masculinity and Contemporary Fashions, 1748-1857 (Greenwich: National Maritime Museum, 2007), 53-54.

- Warrant officers were allowed regulation uniforms in 1787, with the most recent changes being made in 1806. For more details on the history and distinctions of warrant officer uniforms, see Miller, Dressed to Kill, 46-48.

- ADM 1/4368 f. 128, April 3, 1812, TNA; Miller includes an image of the buttonhole embroidery from the 1806 surgeon’s collar in her book, see Miller, Dressed to Kill, 49.

- Miller, Dressed to Kill, 48.

- ADM 1/4368 f. 129, April 7, 1812, TNA.

- ADM 1/4368 f. 128, April 3, 1812, TNA.

- Miller, Dessed to Kill, 48-49.

- Miller, Dressed to Kill, 22.