To recognize this year’s 400 anniversary of the 1619 arrival of the first Africans to Jamestown, I will discuss Morris Russell’s 1810 protection pass. This document highlights the contradictions of American citizenship but unfortunately reveals very little about Russell himself.

In 1796 “An Act for the Relief and Protection of American Seamen” allowed American sailors to pay 25 cents for a document that proved their American citizenship. In a letter from Attorney General Charles Lee to President George Washington the following July, Lee wrote that there were many problems with the act, namely that “it does not specify or prescribe how the proof of the citizenship of a Seaman is to be authenticated” and also “the citizens in the several states naturalized after the 26th of march 1790 … are neglected & concerning them no provision has been made.”1 Lee outlined his considerable criticism of the bill, especially that the proofs allowed for citizenship were “too loose” but never mentions another group totally ignored by it; namely free African American seafarers.

In 1813, two American ships, Revenge (14) and Governor Gerry (18) were captured by a squadron of British ships. H.M. Ship Royalist (16) took on board parts of the crews as either prisoners of war or newly pressed men. The captain, Gordon Bremer, wrote to Lord Keith in Plymouth about a specific captured crew member, Morris Russell. Russell was an African American seaman and because of his race, Bremen didn’t know what to do with him. Keith forwarded his inquiry to the Admiralty, who confirmed that it was acceptable to impress Russell unless it could be proved he was actually American.

Russell was able to present a document he had signed in 1810, and took oath that he was a citizen of the United States.

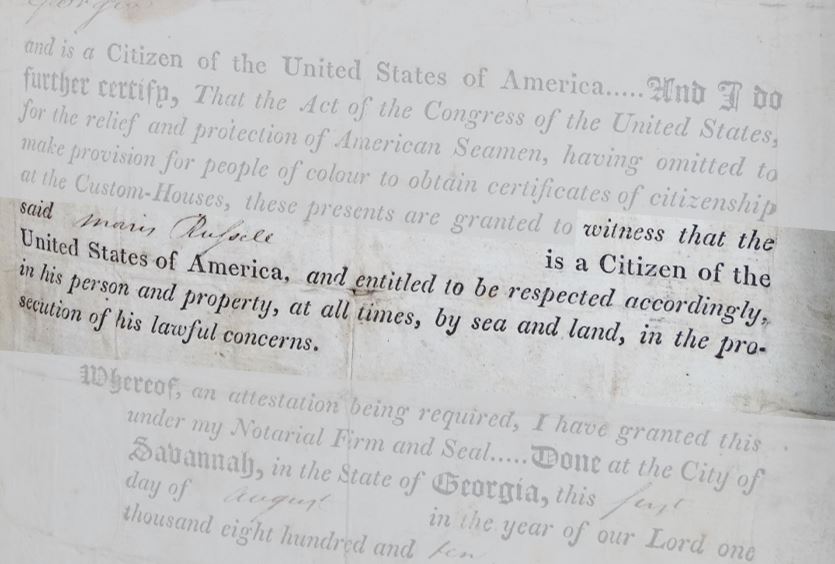

Russell presented his protection pass to Bremen. This document was signed on August 1, 1810, at a customs house in Savannah, Georgia, witnessed by public notary Richard M. Stites.2 The document is interesting for many reasons. It gives a vague description of Russell, who was about 20 years old. He was nearly five feet nine inches in height, and was born in Savannah. Though it does not give any further physical details, the document is specifically a “provision for people of colour to obtain certificates of citizenship” and continues that “the said Morris Russell is a Citizen of the United States of America, and entitled to be respected accordingly, in his person and property, at all times, by sea and land, in the prosecution of his lawful concerns.” The document acknowledges the omission of free Black sailors in the original 1796 act and declares Russell an American, due the consideration and protection of his home nation.

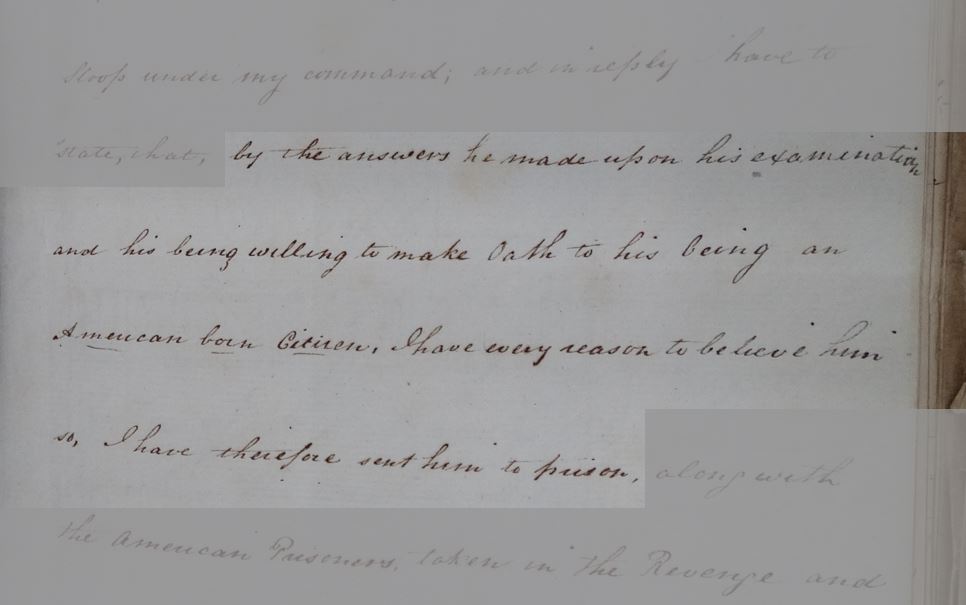

“… by the answers he made upon his examination and his being willing to make Oath to his being an American born Citizen, I have every reason to believe him so. I have therefore sent him to prison…” Captain Gordon Bremer to Admiral Lord George Keith, 14 June, 1813. ADM/1/153/355, June 18, 1813, The National Archives [TNA].

As the nineteenth century progressed, the right of African Americans to carry papers which declared their freedom and their citizenship became more and more fraught. First, opinions about slavery became increasingly polarized in the antebellum period. Ideas about who was and was not an American were also challenged as the United States received immigrants and northern states rejected slavery. And finally, the creation of an ostensibly objective government bureaucracy made it increasingly difficult to deny that documents like Russell’s were evidence of citizenship, despite a Supreme Court decision which maintained the opposite.4

Over the course of the 19th century polarized opinions on slavery, anxieties about whiteness, and the creation of an objective bureaucracy combined to make free Africans “dubious citizens”.

This was all the more complicated because the Constitution recorded no official definition of who was “American”. Congress, however, described naturalized citizens as white men who had lived in the United States for two years.5 From this it is clear that despite no official description of an American, they were assumed to be white and male, with some sort of residence in America.

“…witness that the said Morris Russell is a Citizen of the United States of America, and is entitled to be respected accordingly, in his person and property, at all times, by sea and land, in the prosecution of his lawful concerns.” Protection papers for Morris Russell, signed by Richard M. Stites, public notary at the customs house in Savannah, Georgia, August 1, 1810. ADM 1/153/355, June 18, 1813, TNA.

In 1857 the Dred Scott decision declared that Africans could not be citizens because they were not treated as citizens, a cruel legal catch-22. The inability for Africans born in America to be issued passports was an important part of the case’s evidence.6 Of course, as Russell’s paper shows, they could get papers which declared they were citizens, it was simply that their papers were parsed as “certificates” and Africans themselves were made “dubious citizens”. The American government allowed the physical appearance of non-white Americans to overrule the authority of the documents they carried.

Therefore both the idealistic institutions of the United States and also its own bureaucratic authority were readily contorted to make room for slavery, something from which the nation has yet to recover. Citizenship was made “separate but equal”, a condition which continued to be foundational to the treatment of African Americans after Reconstruction. Whites were granted passports, which enshrined their citizenship, while Blacks received certificates, which ostensibly protected their labour from foreign harassment, but did not make them citizens. In this way, these seemingly empowering documents become sullied; it is clear from the roots of American protection papers as a management tool for property and labour that Russell’s passport was primarily for American shipowners and captains to avoid losing workers to British impressment raids.

The War of 1812 was ostensibly fought because the British would not recognize the citizenship of naturalized Americans but the United States did not yet know was an American citizen was.

The impressment of American sailors was one of the instigating factors of the War of 1812. Whether or not it was pretext for war is besides the point; at the time US Congressmen believed that the failure of the British to recognize their sovereignty in designating foreign sailors as neutral and naturalized American citizens was outrageous enough to act as an important talking point for conflict with Britain, regardless of their other goals.7. This means that the United States fought a three-year conflict over the right of people who immigrated to America to feel safe and protected by their new nation. However, it is also clear that America was already in the process of creating a two-tier citizenship consisting of white citizens and non-white “dubious” citizens. This legacy continues today, as questions about the loyalty of Jewish citizens are raised, passport-carrying minors are unlawfully detained, and citizens born in the United States are denied passports.

When Russell was captured by the British in 1813, he risked either being impressed or being sent to England to be a prisoner of war. He was given an oppertunity to work for the British instead of going to prison, but he did not. He gave his protection paper to Bremer and took oath that he was an American citizen. Bremer, on receipt of this document, accepted that Russell was “an American born Citizen“.8 It would take over fifty years for the United States to officially come to the same conclusion.

Further Reading

Examples of seamen’s protection certificates.

Stein, Douglas L. “Seamen’s Protection Certificate: American Maritime Documents 1776-1860.” Mystic Seaport Museum: Collections and Research. https://research.mysticseaport.org/item/l006405/l006405-c041/. [accessed 26 August, 2019].

An extract of the Act for the relief and protection of American seamen.

“An Extract of the Act, Entitled ‘An Act, for the Relief and Protection of American Seamen; Passed in the Fourth Congress of the United States, at the First Session, Begun and Held at the City of Philadelphia, on Monday the Seventh of December.” Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.22301000/. [accessed 26 August, 2019].

The essay that inspired this document discussion.

Hannah-Jones, Nikole. “America Wasn’t a Democracy, Until Black Americans Made It One.” The New York Times. August 14, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/black-history-american-democracy.html. [accessed 14 August, 2019].

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Primary Sources

TNA, ADM 1, Admiralty In-letters.

George Washington Papers, Founders Early Access. https://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/.

Secondary Sources

Robertson, Craig. The Passport in America: The History of a Document. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Trautsch, Jasper M. “The Causes of the War of 1812: 200 Years of Debate.” The Journal for Military History 77 (January, 2013), 273-293.

NOTES

- Lee’s emphasis. Charles Lee to George Washington, 4 July 1796, Founders Early Access. https://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/default.xqy?keys=FOEA-print-01-01-02-0682. [accessed 22 August, 2019].

- ADM 1/153 f. 355, June 18, 1813, TNA.

- Craig Robertson, The Passport in America: The History of a Document (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 15-16.

- Robertson, The Passport in America, 125.

- This definition was enacted in 1790; in 1795 the duration was extended to five years, then reduced back to two years in 1802. Robertson, The Passport in America, 127-128.

- Robertson, The Passport in America, 148.

- These include expansion into British North America and the continued conflicts with Tecumseh’s Confederacy, which the British supported. However, the causes of the war were probably also rhetorical, perhaps more tied up with continued grievances with Britain from the American Revolution and the changing character of the American people. See Jasper M. Trautsch, “The Causes of the War of 1812: 200 Years of Debate,” The Journal for Military History 77 (Jan., 2013), 273-293.

- Bremer’s emphasis. ADM 1/153 f. 355, June 18, 1813, TNA.