Thank you to Henry Jacob for this wonderful post about depictions of Colonial representations of Panama and Central/South America in the early 20th century. Henry is a Yale graduate and currently completing an M.Phil. in World History at the University of Cambridge as a Henry Fellow. During the 2022-2023 Academic Year, he will be a Fulbright researcher in Panama. Jacob studies Anglo-American designs for inter-oceanic transit in tropic and polar regions. His writing has appeared in numerous peer-reviewed and online publications, including The Latin Americanist. He has won various grants as well as departmental and university-wide awards, including Yale’s highest undergraduate honor. Outside of scholarship, Jacob leads two global organizations (Society of Undergraduate Humanities Publications) and (Publish & Prosper) devoted to student publishing. You can find more information about his work here.

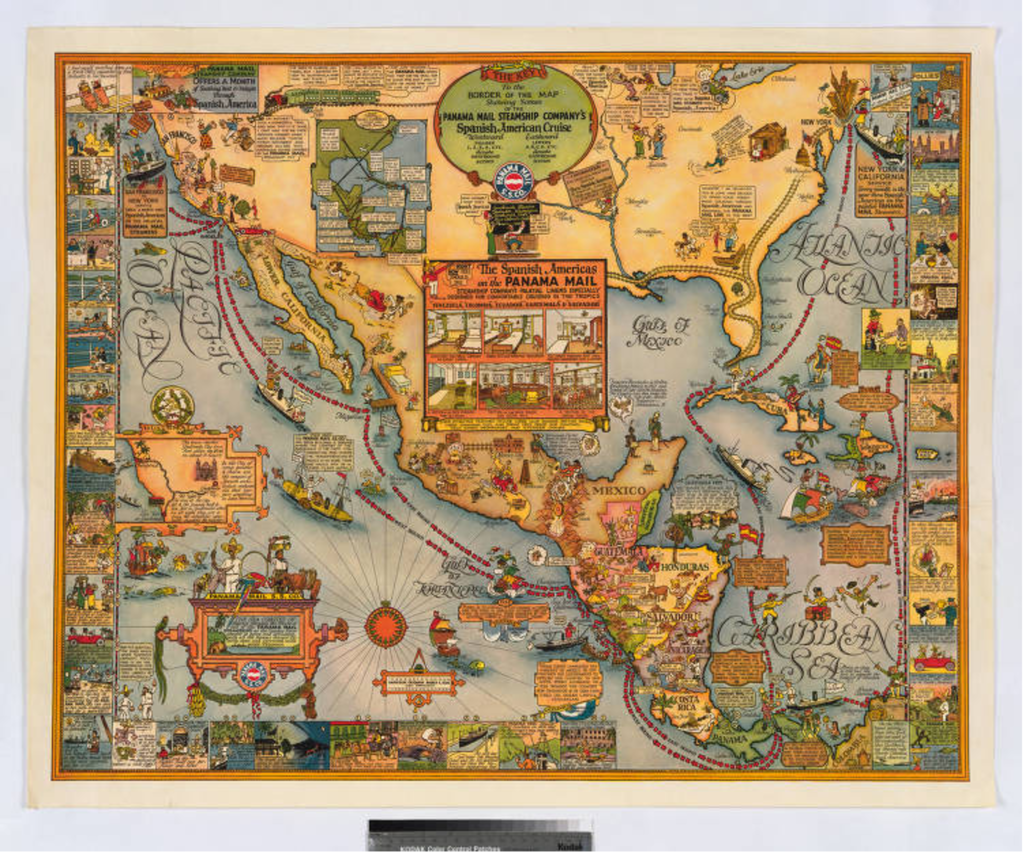

Harrison Godwin’s 1928 pictorial map, The sea coastes of America shewing the ports of call of the Panama Mail Steamships as the country there aboutes is lying and situated, with all the havens thereof, exactly done and corrected with great diligence, confronts its viewer with a visual cacophony. 1 However, what appears to be a multifaceted narrative is actually a narrow one. Godwin’s The Sea Coastes presents a unified argument: the tropics may seem threatening, but ultimately can be rediscovered and tamed through the company that commissioned the map, the Panama Mail Steamships Company (PMSC). Indeed, by accenting the map with famous explorers, Godwin suggests that tourists can become cruise line conquistadors. The map’s iconography and text reassure its presumably white and affluent clientele that they will have access to exciting far-away places without sacrificing the comforts of home. Godwin advances this thesis in two ways. First, the map collapses temporality by fusing past and present; it renders the arc of history as continuous, starting with Spanish colonization and culminating with the PMSC. Next, Godwin simplifies and sanitizes the exotic to appeal to sightseers wary of the foreign. Multiple images present native peoples as voluntary participants in transforming the natural resources and indigenous culture into appealing commodities, ready to be enjoyed by the traveler. Moreover, depictions of the steamship at the center of the map persuade prospective customers that they can sail in the luxury to which they are accustomed. Godwin’s use of cartoons renders playful or pristine what might otherwise seem frightening or unclean. In the end, The sea coastes shows that the PMSC enables vacationers to become the ultimate bourgeois adventurers.

Figure 1: A starburst compass gives a measure of gravitas to the map.

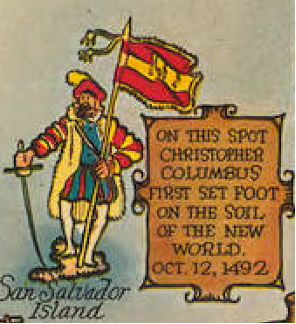

Figure 2: Christopher Columbus, with pompous posture and regal attire, poses next to an identifying scroll. This image signals the accessibility of history.

This map conflates the past and the present to show that tourists can participate in a single narrative of colonization; Godwin suggests that clients can reach a long-ago time through travel with the PMSC. Indeed, the cartographer represents the company as the apotheosis of the imperial mission. The starburst compass and the baroque cartouche elevate the graphics, lending a level of old-world legitimacy to The Sea Coastes, as shown in figure 1. Moreover, a loop of red dashes and arrows mark the cruise’s grand “East Bound” and “West Bound” voyages; when seen from a distance, these tracks resemble those found on antique maps, which trace discoverers’ circumnavigations across the globe. 2 Godwin presents the period from 1492 to 1928 as harmonious and uninterrupted, simplifying the history of the Americas. Instead of presenting a chronological timeline that reads from left to right, Godwin indicates bygone centuries through floating visual signs. For example, in figure 2, an official placard identifies Christopher Columbus in the middle of the Atlantic, staking his claim on San Salvador. This destruction of a linear narrative opens the possibility for vacationers to enter the past. With all of the Spanish Americas before them, potential customers can imagine themselves as daring explorers.

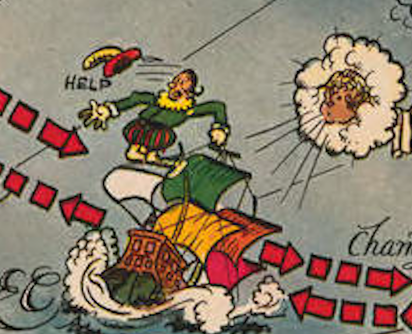

Figure 3: The physical dislocation of the flailing Alvarado implies the disarray of the Spanish imperial mission. His boat not only sinks into the water, but Alvarado himself hovers in the air, disconnected from his vessel.

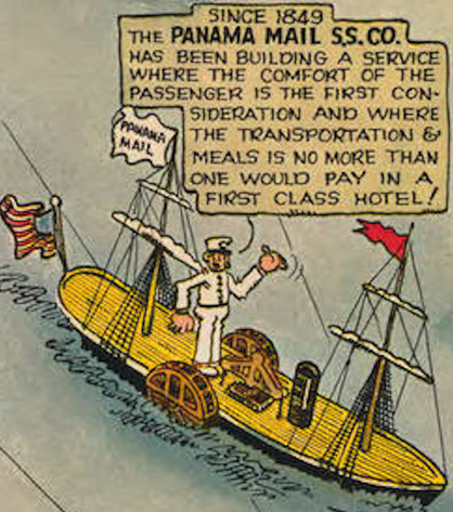

Figure 4: The captain of the Panama Mail S.S. Co. (PMSC) delivers a monologue on the virtues and “comfort” of the PMSC.

At times though, Godwin goes further, brashly overwriting the accomplishments and passages of former discoverers. As portrayed in figure 3, the PMSC cruise ship literally bumps Pedro de Alvarado, a 16th century conquistador, off course. The red lines traverse through and over Alvarado, challenging his place on the map; the flustered explorer cannot even control his own boat; he screams “Help” as a gust of wind shoves his rickety ship into the ocean’s swells. 3 Godwin does not allow the buffoon Alvarado even a shred of dignity: his plumed hat flies off his head. This degrading image highlights the supremacy of the US and the PMSC. After all, figure 3 depicts a pristine Panama Mail Boat, decked with an American as well as a company flag, sweeps past. Unlike the floundering Alvarado, the captain of the PMSC stands strong and erect. This commander and the flags suggest that the corporation and country wield control over the sea in a way that the Spanish never could. Godwin’s treatment of Alvarado is notable but not isolated: the PMSC’s voyage often supersedes those of the past. Even more, the bright dotted lines – specifying the PMSC’s route – encircle most of the Americas. This visual cue gives the impression that the cruise line, and by extension its passengers, displace earlier claims for ownership that conquistadores made. Thus, the map hints that tourists will replace discoverers and that the routes of the PMSC will improve upon prior excursions.

Figure 5: This image represents a man with a piece of gold in one hand and a pickaxe in the other, simplifying the process and ignoring the danger of production.

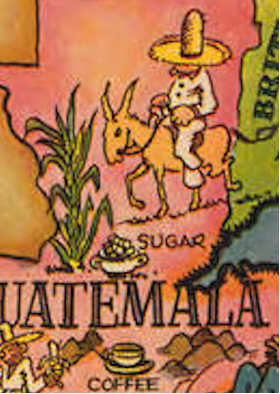

Figure 6: This portion of the map shows a man passing by sugarcane and a cup of sugar on his horse. Below him lies a steaming cup of coffee, ready to be drunk. He functions as a passive spectator to the cultivation of exports.

Godwin collapses not only history, but also the cultivation of exports; in so doing, the cartographer separates the difficulty, and sometimes even the laborer, from labor itself. As a result, he assures potential customers that they will become beneficiaries of the land, which appears so rich that it invites easy exploitation. Often, the indigenous peoples happily convert the most coveted resources into commodities: precious metals as well as delicious drinks and foods; these resources have been compressed into products for the delight of the tourist. Godwin disregards the inherent hazards of mining when he illustrates a Nicaraguan painlessly pulling a shining gold nugget from earth, which is represented in figure 5. More often than not though, Godwin removes the worker from the steps of creation, pairing depictions of the resources with the completed products. Figure 6 displays that in Guatemala, a bowl of sugar rests at the foot of the plant from which it comes; this juxtaposition ignores the brutal difficulty of the harvesting cane; indeed, the man in an oversized sombrero, ambling by on his horse, seems unattached to the industry; he provides only local color. At other times, the cartographer completely untethers the product from its fabrication, such as the cup of the coffee below the sugar. All of these omissions highlight the effortlessness of extraction. Thus, Godwin satisfies visitors that they can amuse themselves without the discomfort of guilt or fear of hostile natives.

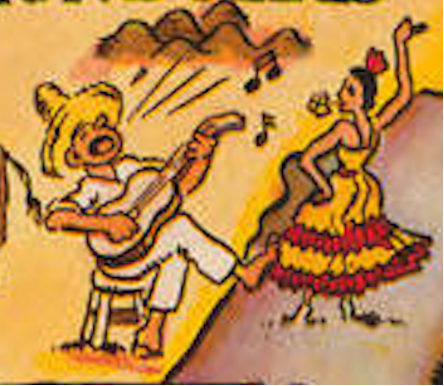

Figure 7: Exotic culture can be found along the border between Honduras and Nicaragua; a man with a guitar sings and a woman with a flower in her teeth dances.

Godwin frames not only the resources, but also the culture of Latin America as something for travelers to consume. The cartographer shows a Honduran musician singing and strumming on his guitar, while a Nicaraguan woman dances Flamenco. These images in figure 7 suggest that vacationers can acquire legitimate ethnic experiences during their excursions. Figure 8 demonstrates how Godwin also includes a cartoon panel along the map’s border of a sightseer with an enormous heap of tangible trinkets. The cartographer promises that visitors will “find everything from household shrines and lottery tickets to genuine guadalajara pottery.” 4 The word “everything” evinces the voracious appetite of Americans for material goods. More significantly though, Godwin fails to distinguish between the sacred and the banal; travelers can buy authentic holy pieces or local crafts as they indulge in mindless games of chance. The tourist’s heap of goodies implies that during a sole shopping spree, he procured a large number of alluring objects at a reasonable price. Although this representation undermines the sanctity of the artifacts, it enhances the map’s message that potential customers can gather (and transport home) all that Latin America offers. In this sense, Godwin depicts commercialism as a form of discovery and conquest.

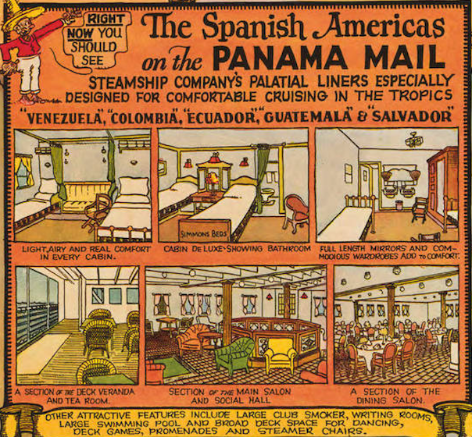

Figure 9. Phrases such as “comfort” (used twice), “attractive features,” and “deluxe” stress the safeness and grandeur of the accommodations.

Godwin suggests that guests need not confront the inconveniences of exploration while embarking on this acquisitive adventure. Indeed, in the center of the map lies a prominent advertisement, as shown in figure 9, which emphasizes the boat’s spotless opulence; this section seeks to highlight how these “palatial liners [are] especially designed for comfortable cruising in the tropics.” 5 That phrase captures the map’s central message: PMSC allows tourists to traverse exotic lands without risk. The top three panels of this ad display the liner’s private accommodations and the bottom three its public areas, offering snapshots of the pleasures vacationers can relish alone or as a group. The images of private cabins emphasize their cleanliness. The linens on the beds in all three rooms, regardless of the accompanying amenities, are crisp white, neatly manicured for respite. In contrast, the bottom picture-frames suggest how travelers might hobnob with equally wealthy patrons in sumptuous, colorful “salons” or on an airy “deck veranda.” 6 The array of chairs – from plush velvet to casual wicker – hint at the ways that passengers can relax and socialize. Additionally, because these pictures are unpopulated, they appeal to clients’ imaginations. Potential consumers can fantasize how they themselves would luxuriate. Above all, this advertisement promises that vacationers can appreciate familiar surroundings while embarking into unknown territories.

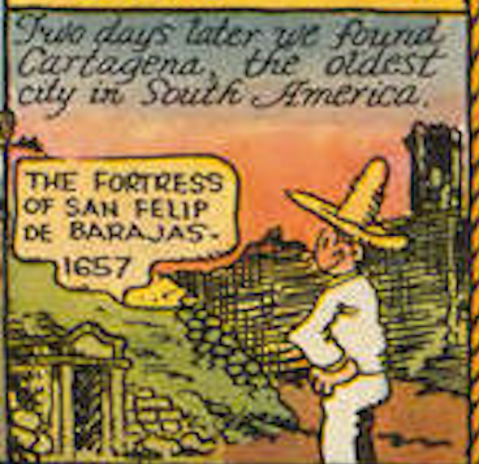

Figure 10: Godwin rewrites history in his cartoon boxes, allowing foreigners to stake their claim over Latin America in the past and present.

Godwin’s crowded map appeals to his audience’s desires; he also preys upon their fears. The sea coastes argues that the privileged tourists who join the PMSC cruise will be able to realize their dreams and stay safe. By joining this trip, they will not only keep up with, but actually surpass, the Joneses, through exposing themselves to the ancient wonders of a vast world. One cartoon, included as figure 10, explicitly promises travelers access to the past with a line of text that reads, “We found Cartagena, the oldest city in South America.” 7 A grinning white speaker stands before the San Felip De Barajas fortress; he appears proud of tracking down the site, as if for the very first time. Even this man’s jaunty sombrero, offsetting his immaculate outfit, signifies his cosmopolitan coolness – and his appropriation of another culture. However, the map also seeks to allay a sightseer’s fear of the foreign. Godwin seems aware that potential customers might worry over the cleanliness of another country or the friendliness of its inhabitants and he ably addresses these anxieties. The ship is scrubbed down and the people awaiting visitors in the ports are welcoming. Even the fun and familiar look of the cartoons offer visual reassurance. Thus, those with enough money to board the PMSC can play conquistador and enjoy a curated experience in the tamed tropics.

Bibliography

Godwin, Harrison. Map. Panama Mail S.S. Co.: The Sea Coastes of America Shewing the Ports of Call of the Panama Mail Steamships as the Country There Aboutes Is Lying and Situated, with All the Haven Thereof. Panama Mail S.S. Company, 1928. From Huntington Library, John Haskell Kimble Collection. https://hdl.huntington.org/digital/collection/p9539coll1/id/12336/. (accessed September 25, 2020).

- Godwin, Harrison. Map. Panama Mail S.S. Co.: The Sea Coastes of America Shewing the Ports of Call of the Panama Mail Steamships as the Country There Aboutes Is Lying and Situated, with All the Haven Thereof. Panama Mail S.S. Company, 1928. From Huntington Library, John Haskell Kimble Collection. https://hdl.huntington.org/digital/collection/p9539coll1/id/12336/. (accessed September 25, 2020). All images from this point are taken from this map.

- ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.