Thank you to Heather Haley for this fantastic article on naval medicine in the age of sail Royal Navy, and about medicine chests specifically.

Naval surgeons in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries endured often intolerable working conditions in damp, confined spaces. With little room for their equipment, surgeons conducted operations and tended wounded shipmates in a poorly-ventilated candle-lit space below the waterline as the vessel itself oscillated violently by the recoil of cannon fire in the midst of pitched battle. In addition to these harrowing situations, surgeons attended all courts martial that resulted in physical disciplinary action, including flogging.i In fact, the most common, if infrequent, wounds sustained by seamen—lacerations and bruises—resulted from floggings conducted by the captain as a means to maintain order and discipline.

During the Napoleonic Wars, a sentence of several hundred lashes was indicative of the severity and nature of the crime, but the presiding surgeon would often halt the punishment after one hundred lashes or when the sailor exhibited signs of severe exhaustion or unconsciousness. Upon release, the seaman was placed under the care of the surgeon, who cleaned the wounds with brine and applied salt packs to prevent infection. Victims of flogging typically recovered after months of intensive care by the ship’s surgeon, but bore horrendous scars for the remainder of their lives.ii The consequences of such wounds sustained by disciplined crew members included pain, blood loss, and infection. Pain, while incapacitating, ultimately subsided and blood loss, if not immediately addressed through cauterization or sutures, could be fatal. But the greatest risk to servicemen was disease—typhoid, malaria, and typhus fevers—which resulted in the deaths of many crew members. Immediately rendered incapable of completing their daily duties, let alone fighting in combat, seamen who fell victim to contagious infections were isolated and placed under the care the ship’s surgeon.iii

The number of surgeons on board a Royal Navy vessel correlated to the ship’s rating (see Table 1). Rarely did a vessel maintain a full medical complement since surgeons and their mates, or surgeon’s assistants, were either already engaged with another patient, altogether absent, or on rare occasion deemed incompetent by the captain. In times of great stress, injured crew members received limited attention. Mirroring the simultaneous situation in the Army, surgeons were in short supply. There were 1,250 surgeons in a British Army that increased to 300,000 by the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars. The ratio of Royal Navy surgeons to crew was disproportionate as there were only about 1,450 doctors for approximately 130,000 sailors. With an average ratio of one surgeon to every 100 men, this was twice the proportional provision witnessed in the Army.iv

Table 1. Allocation of Naval Surgeons by Rate of Ship

|

Rate |

Guns |

Men |

Surgeon |

Surgeon’s Mates |

| 1 |

100 |

880 |

1 |

5 |

| 2 |

84 |

750 |

1 |

4 |

| 3 |

74 |

600-700 |

1 |

3 |

| 4 |

60 |

400-435 |

1 |

2 |

| 5 |

36 |

240 |

1 |

2 |

| 6 |

28 |

200 |

1 |

1 |

| Sloop |

12 |

80-110 |

1 |

1 |

| Bomb Ketch |

8 |

60 |

1 |

0 |

| Fireship |

8 |

45 |

1 |

0 |

| Yacht |

8 |

40 |

1 |

0 |

Source: Michael Crumplin, “Surgery in the Royal Navy during the Republican and Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815),” in Health and Medicine at Sea, 1700-1900, ed. David Boyd Haycock and Sally Archer (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2009), 72.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the professional standing of a surgeon was inferior to that of a physician. There were only a handful of physicians assigned to vessels in the Georgian Navy, only one to each of the larger squadrons, but there was always one medical man aboard every vessel upon whom the officers and subordinates relied for medical treatment: the ship’s surgeon. The social status and professional ability of surgeons varied. While at least two former surgeons were honored with a knighthood, “their pretensions to gentility were insecure.”v A dubious challenge for historians is uncovering the social background of naval surgeons. However, historian M. John Cardwell shed light on this subject through his quantification of the data he found in the wills of Navy surgeons collected by the Navy Office. These documents list the name, rank, ship, and disposable property of the testator. Submitted between 1786 and 1807, with the exception of one dated 1817, these wills listed the parents of the testator as executors and beneficiaries, often providing the address and occupation of the family patriarch. This small sample gives a general and reliable picture of the often humble social beginnings of English naval surgeons of the Napoleonic Wars.vi

Clearly, members of the professional classes primed their offspring for medicine. However, these medical professionals appeared to have been simple surgeons or general practitioners. The wills did not identify a single physician, a position “which occupied the height of medicine’s professional and social hierarchy.” The only patriarchs who could claim the status of gentleman were clergymen and these men made up a small minority in this sample. The data suggests that the fathers of most naval surgeons were engaged in trade, business, or manufacturing and that the men engaged in agriculture were minor landowners, estate mangers, or tenant farmers. The bulk of these families were financially prosperous, the most fortunate earning an annual income of between £200 and £300. However, the majority of these families, with the exception of clergymen, would have had little formal schooling. Thus, the overall impression of Cardwell’s sample is that the families of naval surgeons lived in relatively modest circumstances and by launching their male heirs into “the gentlemanly profession of medicine, many of these families were entering into uncharted waters.”vii

Table 2. Occupation of Naval Surgeons’ Fathers

-

Occupation No. Agriculture 5 Professions Administration

Architect/Surveyor

Armed Forces

Ecclesiastical

Medicine

1 2

1

4

7

Business/Trade/Service Builders

Mariners

Manufacturers

Merchants

Laborers

Servants

Tradesmen

1 3

3

8

1

1

2

Independent Gentlemen 1 Total 40

Source: M. John Cardwell, “Royal Navy Surgeons, 1793-1815: A Collective Biography,” in Health and Medicine at Sea, 1700-1900, ed. David Boyd Haycock and Sally Archer Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2009), 42.

In a professional structure that imitated the eighteenth-century guild systems that churned out luxury textiles, fabrics, and ceramics to the middling and upper classes, The Company of Surgeons formed in 1745 at the demand of qualified surgeons who apprenticed with a physician or surgeon. Under the previous system, the Company of Barber-Surgeons, training was limited to the treatment of casualties only. In order to protect their interests, the Company denied naval surgeons the ability to treat disease. Increasing complains to the Company of Barber-Surgeons from ships captains about increasing casualties from disease prompted the excuse from the guild that they had no knowledge of disease and, therefore, were not culpable. At the insistence of surgeons eager to learn how to treat infections and reduce the already increasing mortality rates among Royal Navy servicemen, the Company of Surgeons allowed them to do so. Armed with additional knowledge in anatomy, botany, and chemistry, naval surgeons tackled contagious diseases like ship fever (typhus), the gripes and fluxes (dysentery and typhoid), smallpox, measles, malaria, yellow fever, scurvy, beriberi, food poisoning, venereal diseases, and pleurisy and catarrhal fever (colds and sometimes pneumonia or tuberculosis).viii

Central to the medical profession and the survival of sailors aboard navy vessels was the maintenance of a medicine chest. In the period between the American Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, surgeons of the Royal Navy had to procure medical instruments at their own expense.ix Prior to accepting their commission, the ship’s surgeon had

The Company of Surgeons, later renamed the Royal College of Surgeons upon receiving a royal charter in 1800, took great interest in the surgeons and instruments they approved. As medical and pharmacological enhancements came into professional purview, surgeons were not only notified of improvements in the treatment and care of patients, but also the suggestions for remedies and, by extension, the objects to be stored within their medical chests. In fact, discussions of recent innovations in the medical practice frequently circulated in a range of primary sources—medical journals, pamphlets, and manuals—highlighting, for instance, the advancements in the treatment and prevention of disease and the restoration of the human body as a result of suspended animation from incidents of flogging, for example.xi

Image 1. Medicine chest belonging to Sir Benjamin Outram and reputedly used at the battle of Copenhagen 1801. Photograph courtesy Royal Museums Greenwich.

Housed in the extensive collections at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, is a mahogany medicine chest owned by naval surgeon Sir Benjamin Fonseca Outram, purportedly used in the Napoleonic Wars at the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801. The verdant felt-lined compartments that border the interior of Outram’s medicine chest contain glass bottles and vials of varying sizes, which likely held medicinal herbal mixtures such as powdered rhubarb, Epsom salts, sulfur, lavender water, chamomile, and ipecac, to name a few.xii The most intriguing aspect of this collection is a circular cardboard box containing grain and dram counterweights for the small hand-held brass balance (not pictured). Wooden-handled flat metal pallet knives, a small cylindrical glass beaker that measures up to eight fluid ounces, and a stone mortar accompanied by a glass pestle round out the collection.xiii While it is unclear when or from which purveyor Sir Outram purchased this medicine chest, the object itself and its contents are indicative of the eighteenth century trend of a professional object that ultimately transcended into domestic use among elites as a luxury item. Additionally, this medicine chest, its contents, and related medical journals are emblematic of the curious juxtaposition facing late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century medicine: the meticulous attention given to the practical advances in the profession and the paucity of medical instruments and remedies.

The owner of this medicine chest, Sir Benjamin Outram, was one of the testators in Cardwell’s aforementioned statistical data on patriarchal occupations. The son of a merchant ship’s captain, Outram was first employed in the medical naval service in 1794. He graduated from the University of Edinburgh in 1809 and became a Licentiate of the College of Physicians in 1810. During the Napoleonic War, he performed his professional duties under great stress and received a medal and clasps for recognition of duties performed during firefights against the French vessels Nymphe, Boadicea, and Superb. In addition, Outram was a veteran of Sir James Saumarez’s victory at Algeciras in 1801 and rose to become Inspector of Fleets and Hospitals in 1841. He received a knighthood in September 1850.xiv

Imitating the German wunderkammern—or cabinet of curiosities in which eighteenth century social elites stored and displayed a range of objects intended to spur curiosity and intellectual discussion—manufacturers intended medicine chests to remain open, the contents of which were on full display to inquisitive viewers. However, the cabinet of curiosity and the medicine chest differed in regards to organization. The wunderkammern of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries demonstrated a lack of systemization as specimens from all corners of the world were eagerly jumbled together—the only thing uniting them was the fact that the objects themselves were curious or exotic.xv Many of the chests dating from the 1770s were small, easily portable, and contained anywhere from six to twelve bottles priced either at sixteen shillings or one pound, eight shillings, respectively. Similar to the cabinet of curiosity, these early chests were simple and had no compartments or dividers, which made finding specific contents with any swiftness nearly impossible. Thus, by the end of the century, the chests grew to contain 30-60 items and were partitioned and organized according to accepted professional medical practices. Druggists and apothecaries, who affixed their own labels to the phials and bottles contained within, purchased these chests from wholesalers of medical and pharmaceutical goods or directly from medicine chest manufacturers.xvi

Medicine chests, additionally, reflected the virtues of and appreciation for nature as emphasized by Enlightenment intellectuals. As a microcosm of advancements in intellectual thought, medicine chests physically embodied the control, manipulation, and improvement of the natural world. The careful selection of medicinal concoctions of herbs, spices, and liquids cultivated from the earth and thoughtfully organized within the chest resulted from decades of enhancements in the medical profession. “Patent medicines” predate the Elizabethan Era when English sovereigns granted monopolies in all areas of commerce, including pharmacological patents. These patents did not require applicants to record the specifications of their formula or method of manufacturing as a condition for granting a patent. Thus, the term “patent medicine” is usually associated with secrecy and the success of each medicine resulted from the ambiguity that surrounded them.xvii

The majority of medicine chests constructed in England in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were mahogany. There is mention of imitation of these chests in other wood grains by American manufacturers for American and international consumers.xviii However, the imperial cultivation of the lumber through slave labor in the Americas and the domestic manufacture, sale, and ownership of mahogany medicine chests solidified the object’s existence as a luxury item in Great Britain for professional and private use. Historian Jennifer Anderson suggests that the conception of mahogany as a luxury material was largely a cultural construct resulting from the cultivation of tropical hardwoods by a “vast slave-driven imperial network.” While mahogany gained a reputation for its versatility, colonial Americans appreciated its aesthetic properties. When applied with varnish, mahogany maintained a silky, polished surface, saturated with color that brought out the timber’s distinct wood grains. According to Anderson, mahogany in the eighteenth century was utilitarian because of its abundance, precious because it was rare and required import from the Americas, desirable because of its sensuality and exoticism, and respectable because ownership of mahogany objects signified refinement and gentility in elite social circles.xix

Additionally, the British Empire’s insatiable appetite for mahogany required a specialized division of labor known as subcontracting. Similar to the proliferation of new products in a variety of metal alloys by Boulton’s Soho Works that required “subdivided labor either between workshops or between departments of a single factory,”xx mahogany required a labor network that spread across the Atlantic. Tasked with seeking out mahogany and harvesting the resource, enslaved Africans in the West Indies and Miskito Indians and other indigenous peoples in Central America were arbiters of the natural world and central to the transformation of this natural object into a monetary value and, ultimately, a commodity. Their extensive knowledge of the natural world also empowered them with negotiating skills within an otherwise exploitative labor system. The felling of mahogany trees was not easily standardized because each tree presented its own challenges in size, shape, and distance from the water source for transport. Slaves scored each log with their master’s mark before sending them downstream on rafts of 200 or more where they met with larger sea-faring vessels for their transport across the Atlantic.xxi

With the growing demand for mahogany among the British elite, the tropical lumber trade became more palatable for private and jointly-owned merchant vessels since their ships already traveled from North America to the Caribbean “laden with agricultural produce, oak barrel staves, lumber, livestock, dried fish, food stuffs, and English-made textiles and hardware.” However, colonial merchants and ships captains quickly discovered that mahogany was bulky, unlike the easily measured, packaged, and stowed commodities of coffee, sugar, cocoa, and tobacco. Difficult and costly to transport across the Atlantic, expenses associated with conveyance included insurance, landing, wharfage, import duties, and warehouse storage. Upon arrival in England—in a situation similar to that of tea importation from the Far East where professional tea brokers assessed the condition of tea before its deployment to warehouse storage prior to commercial sale.xxii Wood surveyors evaluated, measured, and graded incoming lumber before the commodity changed hands to manufacturers.xxiii

From wood purchase in wharf warehouses to furniture sale, cabinetmakers were central in the diffusion of mahogany as a luxury material. Frequently used as prototypes for American imitations, existing English-made furniture pieces and design schematics allowed manufacturers to become more acquainted with mahogany and with new and more efficient manufacturing processes. A cabinetmaker’s success depended on his “training, skill, and creative intuition” to be able to replicate or adapt designs and translate them into finished products. He needed an intimate knowledge of woodworking to determine what secondary woods he would incorporate into the finished piece. Over the course of the eighteenth century, cabinetmakers increasingly offered imported mahogany as an option for their luxury products, but incorporated cheaper secondary woods for structural and hidden parts.xxiv

As the middling classes redirected their spending habits “towards the virtuous display of finely crafted luxury items used in a context conveying knowledge, taste, and hospitality,” glass became a luxury good among the elite because of its craftsmanship. The introduction of flint glass by George Ravenscroft in the seventeenth century and cut glass by John Akerman in 1719 made London the epicenter for glass marketing.xxv Adding lead to the minerals sand, soda ash, and limestone meant that glass could be colored and cut. This uniquely eighteenth century technology translated to similar markets as the addition of lead allowed for thicker, heavier windows that insulated better. Manufacturers marketed inferior glass not only for windows, but for bottles. At first made of green glass—the thinness only increased the likelihood of breakage—bottles became colorless with the introduction of lead. Alongside the square and cylindrical vials were the wide-mouthed bottles that could hold anything from solids to non-liquid medicaments.xxvi

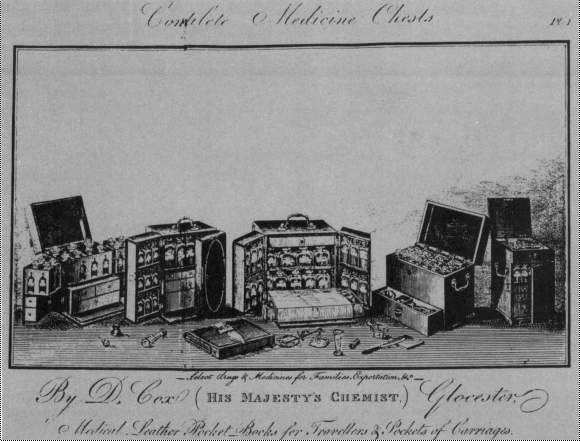

The naval surgeon’s medical chest, like that of Sir Outram, transcended from an essential tool of the medical profession to a luxury item enjoyed by the upper strata of English society, in part, through the distribution of trade cards (see Image 2). According to historian Maxine Berg, the luxury and semi-luxury trades advertised their wares through the distribution of trade cards to repeat consumers. These were small engraved sheets or cards that displayed pictures of the wares, the emblems associated with that particular trade, and sometimes extensive lists of products offered by the proprietor. This form of advertisement was not new to the eighteenth century; in fact, trade cards originate in the Renaissance period with a few surviving examples dating from the sixteenth century.xxvii The proliferation of trade cards as a marketing strategy in the eighteenth century resulted from high excise taxes on newspaper advertisements. Thus, the distribution of trade cards was a cheaper way to market their products, even though proprietors bore the burden for the design, acquisition of materials, and printing.

Medicine chests marketed for domestic use became popular in the last decades of the eighteenth century when chemists, apothecaries, and druggists publicly promoted their use. London chemist Francis Spilsbury published a pamphlet in 1773 in which he commented:

I have frequently taken notice of the Medicine Chests in the cabinet-shops, some containing six bottles, some nine, and some twelve; others larger, with drawers to hold different medicines; which are extremely convenient in any exigency, and would be more universally made use of, if a simple and safe plan could be adopted: and I think it is a pity no person has ever given a hint how to furnish those small ones.xxviii

Spilsbury continued to infer the importance of owning and maintaining remedies in the home, drawing considerable attention to “the many accidents human nature is subject to . . . which would be in a great measure prevented if masters or mistresses of families would keep a small Chest by them.” Circumstances such as travel and isolation in the countryside, when sending for a medical practitioner was especially difficult, served as the reigning justification for the ownership of a medicine chest.xxix

The purchase, maintenance, and use of medicine chests within elite English homes were not only microcosms of Enlightenment ideology, but they reflected the consumption patterns of luxury items. Industrialization and commercial ingenuity in the eighteenth century “was, above all, about consumer products.” The concept of luxury featured prominently in the language of advertising. Distinction, diversity, and individuality were now priorities of elite consumerism.xxx Historian Neil McKendrick argues that in the last decades of the eighteenth century, elites participated in “an orgy of spending” on luxurious and exotic goods, or conspicuous consumption. With sixteen percent of the English population’s exposure to London shops in the mid-eighteenth century, the lifestyle and fashions of the capital city permeated all levels of society. Thus, as the democratization of consumption—or consumption that everyone, regardless of status, had access to—threatened traditional class discipline as a form of social control, elites purposefully purchased luxury objects that set them apart from the middling and lower classes, including medicine chests.xxxi

As a professional object, medicine chests were integral to the survival of Royal Navy servicemen during the Napoleonic Wars. Under the guidance of the Royal Company of Surgeons, Sir Benjamin Outram received additional training and education in the treatment of disease, which was previously unavailable to him. While Outram was responsible for procuring his own medical supplies, the Society of Apothecaries provided him with a considerable list of remedies recommended for display within his medicine chest. Some of these items included diluted acid vitriol, gum Arabic, camphor, opium, and rhubarb.xxxii At the conclusion of their service in the Royal Navy, naval surgeons were free to enter private practice. In so doing, their medicine chests transitioned from the professional to the private sphere.xxxiii As the private medical practice advanced in the capital city in the early nineteenth century, chemists, apothecaries, and druggists capitalized on the market by promoting the use of mahogany medicine chests to the private homes of the aristocracy.

From the cultivation of mahogany to the intricacies of the furniture fittings, the medicine chest was a luxury good that embodied the complexities of subcontracting involved in the production of any single item within the chest. An army of workers—enslaved Africans and indigenous populations, colonists, and planters in the West Indies and Central America, ship captains, sailors, as well as merchants, cabinetmakers, toymakers, and laborers in England and its North American holdings, and chemists, apothecaries, and druggists—were responsible for the felling and transportation of mahogany, and the production and sale of the finished product. Like the inquisitive gaze viewers cast upon the objects displayed in a wunderkammern, mahogany—as the exotic material used to manufacture medicine chests—reflected the “curiosity, suspicion, and fascination with which white people gazed upon nonwhite bodies” in the Americas.xxxiv Ownership of this rarified object remained exclusive to the aristocracy because of the increasing costs associated with the importation of mahogany from the West Indies. By the mid-nineteenth century, medicine chests fell from fashion with the proliferation of medical facilities. For over thirty years, however, these chests were essential in providing “relief and mitigation of the complicated misfortunes of disease” for elite families, their domestic servants, and the neighboring poor until a medical professional could attend to the patient.

References

i# Elisabeth Bennion, Antique Medical Instruments (London: Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1979), 154-5.

ii# N. A. M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649-1815 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2006), 492, 494; Zachary Friedenberg, Medicine Under Sail (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2002), 101.

iii# Matthew H. Kaufman, Surgeons at War: Medical Arrangements for the Treatment of the Sick and Wounded in the British Army during the Late 18th and 19th Centuries (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2001), 1-2.

iv# Michael Crumplin, “Surgery in the Royal Navy during the Republican and Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815),” in Health and Medicine at Sea, 1700-1900, ed. David Boyd Haycock and Sally Archer (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2009), 71.

v# N. A. M. Rodger, The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy (New York: W. W. Norton, 1996), 20.

vi# M. John Cardwell, “Royal Navy Surgeons, 1793-1815: A Collective Biography,” in Health and Medicine at Sea, 1700-1900, ed. David Boyd Haycock and Sally Archer (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2009), 42.

vii# Cardwell, “Royal Navy Surgeons, 1793-1815,” in Health and Medicine at Sea, 42, 43, 44.

viii# Zachary Friedenberg, Medicine Under Sail (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2002), 4, 5, 34.

ix# Jonathan Charles Goddard, “The Navy Surgeon’s Chest: Surgical Instruments of the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic War,” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 97 (April 2004): 191.

x# Regulations and Instructions Relating to His Majesty’s Service at Sea (London, 1731: n.p., n.d.), 129.

xi# John Savory, A Companion to the Medicine Chest; or Plain Directions for the Employment of the Various Medicines Contained in It, with the Properties and Doses of Such as Are More Generally Used in Domestic Medicine (London, 1836), 98, 104.

xii# Thomas Ritter, A Medical Manual and Medicine Chest Companion: For Popular Use in Families and on Ship Board, for the Treatment of the Ordinary Diseases of the Human System, 3rd ed. (New York: S. W. Benedict, 1847), 6, 7.

xiii# “Medicine Chest,” National Maritime Museum, accessed October 1, 2016, http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/69172.html; Gloria Clifton and Nigel Rigby, Treasures of the National Maritime Museum (Greenwich, London: National Maritime Museum, 2004), 86.

xiv# John Gough Nichols, “Sir Benjamin F. Outram, C.B.,” The Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Review, April 1856, 429; Cardwell, “Royal Navy Surgeons, 1793-1815,” in Health and Medicine at Sea, 43.

xv# Christopher Ferguson, “The Exotic in the Material Culture of Early-Modern Europe” (lecture, Auburn University, September 7, 2016).

xvi# J. K. Crellin, “Domestic Medicine Chests: Microcosms of 18th and 19th Century Medical Practice,” Pharmacy in History 21, no. 3 (1979): 125, 126; Lillian C. Richardson and Charles G. Richardson, The Pill Rollers: A Book on Apothecary Antiques and Drug Store Collectibles (Fort Washington, MD: Old Fort Press, 1979), 95.

xvii# Richardson and Richardson, The Pill Rollers, 9.

xviii# Crellin, “Domestic Medicine Chests,” 125.

xix# Jennifer L. Anderson, Mahogany: The Costs of Luxury in Early America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015), 15.

xx# Maxine Berg, Luxury and Pleasure in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 168, 169.

xxi# Anderson, Mahogany, 13, 158.

xxii# Markman Ellis, Richard Coulton, and Matthew Mauger, Empire of Tea: The Asian Leaf That Conquered the World (London: Reaktion Books, 2015), 116.

xxiii# Anderson, Mahogany, 34, 35.

xxiv# Ibid., 39, 40.

xxv# Berg, Luxury and Pleasure, 119, 120, 124.

xxvi# R. J. Charleston, English Glass and the Glass Used in England, circa 400-1940 (London: Allen and Unwin, 1984), 92-93.

xxvii# Berg, Luxury & Pleasure in Eighteenth-Century Britain, 186.

xxviii# Francis Spilsbury, The Friendly Physician. A New Treatise; Containing Rules, Schemes, and Particular instructions, how to select and Furnish Small Chests With the most approved necessary Medicine and full Directions how to apply them, To Which Are Added Many excellent Receipts for particular Disorders (London, 1773), 1.

xxix# Ibid., 2; John Savory, A Companion to the Medicine Chest; or Plain Directions for the Employment of the Various Medicines Contained in It, with the Properties and Doses of Such as Are More Generally Used in Domestic Medicine (London, 1836), iv.

xxx# Berg, Luxury and Pleasure, 6, 11.

xxxi# Neil McKendrick, John Brewer, and J. H. Plumb, “The Consumer Revolution of Eighteenth-century England,” in The Birth of a Consumer Society: The Commercialization of Eighteenth-century England (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982), 10, 20, 21.

xxxii# William Turnbull, The Naval Surgeon; Comprising the Entire Duties of Professional Men at Sea, and Compendious Pharmacopoeia (London, 1806), 393.

xxxiii# Kaufman, Surgeons at War, 4.

xxxiv# Anderson, Mahogany, 295.