Research isn’t usually the way it is depicted in movies and television- invisible ink inscriptions, hitherto undiscovered and uncatalogued manuscripts that you can somehow call up from the depths of the stacks, being chased by armed and ferocious enemies who are hell bent on stealing your documents. Sometimes, though, research does take on a sense of the odyssey, bringing you off well-worn paths to unexpected environs and taking far longer than you would have anticipated.

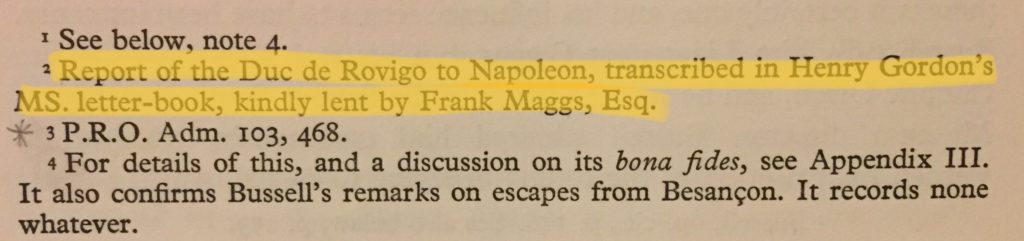

This story begins with a footnote. While major strides have been made in the study of prisoners of war in the last decade, for the Napoleonic wars, at least, there are few ‘core texts’ in the historiography. Of three attempts to discuss British prisoners of war in France during this period, Michael Lewis’ book stands out. Lewis had picked up the subject of prisoners of war while teaching and working with the Society for Nautical research. The fruits of his interest are encompassed by his published summary and description of prisoner William Henry Dillon’s diaries through the SNR, and his book “Napoleon and His British Captives, published in 1962.

Full to the brim with evidence of close research of original documents, attempts at cross referencing, and a nascent database of the prisoners in France, Lewis’ book is frustratingly sparse on citations. Scattered enticingly throughout, I have made chasing down these citations one of my research missions for my PhD. Right in the heart of an intriguing story of a prisoner of war, by the name of Edmond Temple, who escaped by breaking his parole, is a mysterious and unhelpful reference to “Henry Gordon’s letter book”. Henry Gordon was a commander living at the depot in Verdun, and was of some authority. He had been called upon by the French to ratify Temple’s (and several other midshipman’s) parole, and was thus, under considerable scrutiny after Temple’s notorious escape. Needless to say, I wanted that letter book. Would there be more about Temple? Perhaps other midshipman had attempted to escape after he had ratified their word of honour. And these were just the questions relating to Temple and his friends, Gordon’s name had appeared in several other places during my research, and I wanted to know more about his own story.

Unfortunately, hours of scouring the National Archives, National Maritime Museum, British Library, and National Army Museum collections and catalogues turned up no references to material by anyone of that name. I went back to the footnote: was Frank B. Maggs Esq. someone I could trace?

Advice from a fellow PhD student and bookseller, Rachel Roepke pointed me in the right direction, Maggs Brothers Booksellers. After some digging, I found out that Maggs, an old and prestigious company, not only still existed, but that they had been in the habit of producing catalogues of their items for as long as they had been in business.

Back to the archives. Unfortunately, these catalogues had never been systematically collected by the British Library. However, several places, the national maritime Museum included kept a list of the catalogue titles. I browsed through the titles for likely culprits, and made a list for those that seemed like they might cover the right categories, from 1958-1962. Something like fifteen or sixteen titles.

Further exploration in the National maritime museum archives revealed that Lewis’ papers had been preserved, and that these papers not only included his personal and professional correspondence, the original Dillon diaries, but also the notes he had taken while writing “Napoleon and his British Captives”. a literal goldmine for tracing the thought process he had while organising his research and writing up his book.

The top of one page of notes was entitled “William Henry Gordon” (see below). And contained his memoranda on some of the letters. Someone else’s notes, while valuable in their own way, are unfortunately no substitute for the original. And as I had already found to be the case with Lewis’ summarisation of the Dillon diaries, he had a tendency to leave out some of the juicier bits. Besides, his handwriting was practically illegible (a year later, and I still have not gotten to grips with it. So, if you, yes you, can read the text in the picture below, please let me know, I’d love your help!)

I needed to find the catalogue entry for the Letter book. So I emailed Magg’s booksellers. A prompt, polite and, generous response was forthcoming. Magg’s did indeed have a collection of their old catalogues, kept in the office tea room of their Bedford Square premises and I was welcome to look through them (many thanks to Bonny Beaumont for the invitation). Armed with my list, it took a surprisingly short time to locate the entry for:

‘GORDON (Commander Henry), later Vice Admiral, LETTER BOOK kept as a Prisoner of war at Verdun, 1803-12, dealing with the affairs of naval prisoners. 8vo, original sheepskin. 1803-12. 18 pounds 10 shillings.’

Unfortunately, the companies sales records are not kept on site, but are in the care of the British Library. So next steps on the Gordon saga will have to be contacting the archivists at the British Library, in the hopes that the records, held off site, can be consulted and the correct entry found.

Even if I never do get to look at the original letters, tracing the whereabouts of the book has been fascinating.

Nice story. Those old historians and their lack of references, eh?

As for the handwriting, it kinda resembles my own handwriting. Definitely not the nice 19th century clerical hand. I can “translate” easily except for one recurring word. Busy at the moment, but drop me an email if you’re not in a big hurry, and I can help out by translating a sample.