The third part of this series on British naval aircraft prototypes, in contrast to parts one and two, will discuss a specification that was successful and spawned an aircraft with a familiar name. The Blackburn Ripon was, after all, a mainstay of the Fleet Air Arm in the interwar years. The aircraft that was the standard equipment of Fleet Air Arm torpedo flights from the late 1920s to the mid 1930s, however, was the Ripon Mk.II in its various versions. The Mk.I can be regarded as essentially a different aircraft that merely pointed the way to the type eventually adopted. It is a little-known waypoint on the journey between the single-seat Dart and the definitive Ripon II.

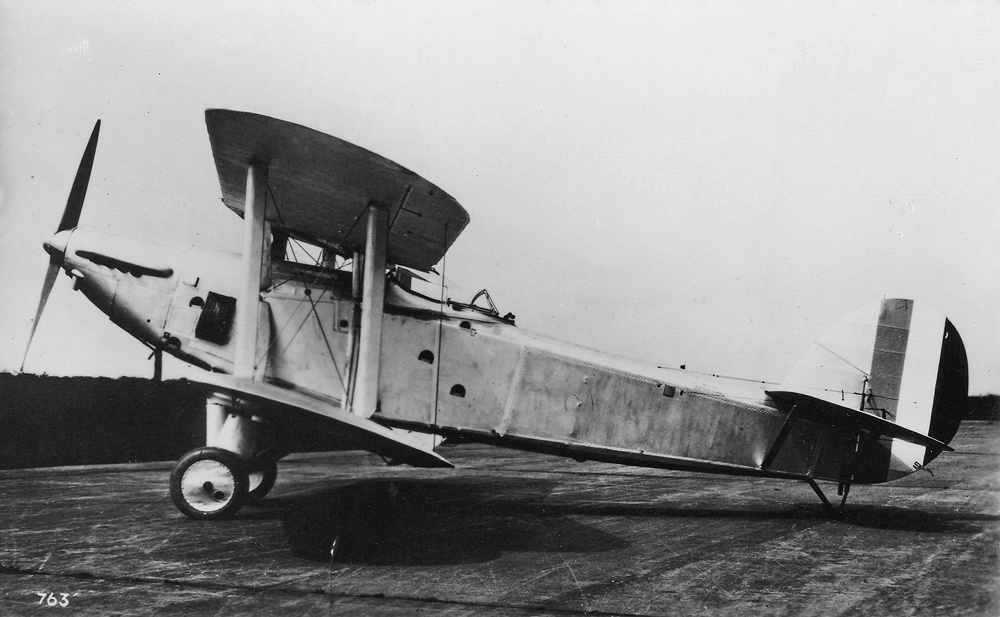

Blackburn Ripon Mark 1 N203 as a landplane (author’s collection)

Specification 21/23 was issued to the industry in 1923 for a ship-based torpedo aircraft to replace the Blackburn Dart (see Part 1) and which was only just coming into service. The new machine had to be able to carry (and deliver) an 18-in torpedo or three 520 lb bombs over a short range. Interestingly, the specification required a long endurance for the aircraft in reconnaissance condition and stipulated a second crew member for navigation and to operate a defensive gun. The Fleet Air Arm’s previous ship-based torpedo bombers had all been single-seat types. Moreover, the service had dedicated reconnaissance machines for which a specification had been issued just the previous year (see Part 2), so the requirements of 21/23 suggest that the Admiralty was already considering combining some functions into fewer types – a move that would not be completed until the mid-1930s and which resulted in the Fairey Swordfish. Conventionally for the time, the new type was requested to have interchangeable wheel and float undercarriages.

Blackburn Ripon Mk.1 N204 as a floatplane (author’s collection)

Three manufacturers, Blackburn, Avro and Handley Page offered designs. Blackburn was a natural choice, as the Northern manufacturer was the existing provider of torpedo aircraft. Moreover, Blackburn had developed the Dart into a two-seat convertible land-and-float-plane known as the Velos for the export market. AJ Jackson in Blackburn Aircraft since 1909 (Putnam, 1968) suggests that design work did not start on the 21/23 design until 1925, which suggests that the Admiralty had set a long deadline for submissions or that details of the requirement were changed, perhaps several times. Indeed, KJ Meekcoms and EB Morgan in The British Aircraft Specifications File 1920-49 (Air Britain, 1994), there was an amendment concerning ‘short range bombing’. In any event, the aircraft penned by Major F.A. Bumpus, Blackburn’s chief designer, was clearly an evolution of the Velos. The aircraft wasknown under Blackburn’s internal designation system as the T.5 for the fifth torpedo aircraft developed by the company, following the Blackburd, Dart, Velos and Cubaroo. The Velos’ two-bay wing cellule was replaced with a single-bay structure, and the general form of the machine was somewhat slimmed down. The general form of the aircraft was, however, clearly derived from the earlier machine in its structure and the shape of its flying surfaces, fuselage and engine installation. The latter very much reflected Blackburn practice since the Dart, with a coolant radiator for the Napier Lion engine set behind a series of shutters to control cooling. As with the Dart and Velos, the cockpit was set high, with upper nose decking that sloped downward to a kink at the engine cowling. The rear cockpit was set close behind the pilot’s cockpit, with a Scarff Ring mounting for the Observer’s Lewis gun.

The T.5’s arrangement was slightly neater than that of the Dart and Velos, which placed their radiators entirely below the engine, while the T.5’s was set a little higher and further forward, beneath the reduction gear, allowing for a reduction in frontal area.

Blackburn Ripon Mk.1 N203 (author’s collection)

Flying surfaces were of a similar shape to those of the Dart and related Blackburn spotter, with rounded tips and sweep-back on the mainplanes, and a rounded fin and (balanced) rudder. The lower wings actually had a slightly greater span than the upper. The rear fuselage was rendered slightly less boxy than that of the Velos as the lower longerons curved gently along their length, though the fuselage was still square in its cross-section apart from the slightly rounded upper decking. The lower wing centre section had a pronounced anhedral, and as the undercarriage, which again was of similar form to the Dart’s, was mounted at the lowest point. This kept the length, and hence, weight, of the undercarriage units to a minimum.

The new aircraft was named the Ripon, in keeping with an RAF-wide policy of naming bomber aircraft after towns and cities. Two prototypes were ordered, N203 and N204, the latter to be delivered as a floatplane. The floats were very similar to those fitted to the Velos, being long, boat-type wooden pontoons with a shallow-vee bottom.

The Ripon was capable of 111 mph at sea level as a landplane and 101 mph as a floatplane. It had an absolute ceiling of 11,250-ft and an endurance of five hours.

The three types submitted – the Ripon, plus the Avro Type 571 Buffalo and Handley Page HP31 Harrow – took part in comparative tests in 1926-1927 at the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment and the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment. During this period, Blackburn moderately improved the design, by fully cowling in the engine and improving the lines of the nose, while also raising the height of the rear deck. Following the trials, the Avro was discarded as a prospective service type – but here is where the unusual nature of the specification presents itself. It appears that, just like with Specification XII (Part 1) and Specification 37/22, none of the machines represented a sufficient advance over existing types. Rather than repeat what had happened with those specifications – cancellation and the issuing of new specifications in due course – the Admiralty and Air Ministry elected to invite the two remaining manufacturers to redesign their submissions to improve performance.

Blackburn took the task very seriously, and the aircraft that emerged, Ripon Mk.II prototype N231, was almost entirely different from the slab-sided Ripon I. The Ripon II’s fuselage was structurally similar to that of the Ripon I, with a tubular steel ‘core’ and wooden rear frame. The form of the fuselage had, though, been completely revamped, with the engine now housed in a slim, pointed cowling and cooling provided by wedge-shaped retractable radiators on each side of the fuselage aft of the engine. The rear fuselage no longer had curved lower longerons, and tapered towards the tail. Both upper and lower decks were curved. The rear cockpit was fitted with a Scarff Ring on first roll-out, but this was later replaced with a Fairey High-Speed pillar mounting to reduce drag and weight, and the cockpit sides were cut down to improve field of fire.

Blackburn Ripon Mk.2 N231 in its original form (author’s collection)

The wings were now composite wood-and-metal units with greater sweepback. The lower wing was still of greater span than the upper but the difference was slightly less. Initially the tail surfaces were similar to those of the Ripon I, but soon N231 received a tall, high aspect-ratio fin and rudder (which was, on later production machines, trimmed to a lower height).

Ripon Mk.2 in its final form (author’s collection)

The new Ripon was evaluated in 1928-29. It was over 20 mph faster than the Ripon I, had a considerably higher ceiling of 15,000-ft and a much better climb rate, though its endurance was reduced from five hours to four. The aircraft was now fit for service, a significant advance on the existing Dart, and would be built in reasonably large numbers (as well as securing export sales to Finland), before being lightly updated into the Baffin, which served into the 1940s. The Ripon I, and the far-sighted decision to persevere with the existing 21/23 designs, allowed the Fleet Air Arm to successfully bridge the gap between generations of aircraft