The second part of this series on British naval aircraft prototypes focuses on a machine and a specification that is all but completely forgotten – the Hawker Hedgehog.

The sole Hawker Hedgehog in its original form with simpler undercarriage and no centre-section fuel tank

Since the requirement that spawned the Blackburn Blackburd in 1918 (see Part 1), the Air Ministry had developed a new system of specifications that would persist until after the Second World War – the now-familiar numerical system with two sets of digits, the second being the year in which the specification was issued, and the first being the number of the specification issued that year – so Specification 37/22 was the 37th requirement of 1922.

In the early 1920s, the Air Ministry seems to have treated the introduction of new types of aircraft much as the process had had been managed during the First World War. Requirements for new aircraft were issued at the same time as, or even before, the types they were due to replace came into service. Specification 37/22 called for a naval reconnaissance aircraft to replace the Blackburn Blackburn and Avro Bison, which had only flown that year and would not go into service until 1923, and the older Parnall Panther.

The rapid introduction of new types was clearly a hangover from the end of WW1 in which front line aircraft could be considered obsolete after a year or less of service. The situation in 1923 was somewhat different, with aircraft of increasing complexity taking longer to get into service, and perhaps more importantly, peacetime removing the urgency for advancing the state of the art. The situation would eventually lead to types remaining in service far longer than was ideal, as with the Fairey Flycatcher which first flew in 1923 and was still in frontline service in 1934, despite the service initially expecting its replacement to be in service within a couple of years.

In 1923 though, the Air Ministry still expected to have to replace types quickly, a situation perhaps reflected in the number of specifications issued (48, compared with 20 in 1930). This led to the issuing of a requirement for a three-place fleet reconnaissance aircraft. The specification seems to have been less onerous than that which it proposed to replace, 3/21, with no insistence on an enclosed cabin for the radio operator and equipment. The resulting aircraft had to have wings that were foldable for stowage aboard ship, a good view for all crew members, and be tough enough to withstand the rigours of shipboard service. Part of the thinking behind the expected new wave of designs was the emergence of reliable air-cooled stationary engines, which offered almost as much power as liquid-cooled powerplants but with much lower weight and complexity, without the gyroscopic forces of a rotary.

The industry responded with an interesting array of layouts for the time. Blackburn offered the R.2 Airedale, a semi-monococque monoplane with high-set, semi-cantilever wings of very low aspect ratio. Avro, by contrast, submitted a triplane, the Type 550. Fairey tried with a development of its successful IIID biplane, the IIIE or Ferret. Hawker’s effort was the T.2 Hedgehog, a conventional biplane. All were to be powered by air-cooled radial engines, unlike the types they were intended to replace (which were driven by the Napier Lion liquid-cooled engine in the case of the Avro and Blackburn, and a Bentley rotary in the case of the Parnall). The Hawker, Fairey and Avro designs were to be powered by the Bristol Jupiter 9-cylinder air-cooled radial, while the Blackburn had an Armstrong Siddeley Jaguar 14-cylinder engine. Handley Page also offered the HP19 Hanley, which had been developed for an earlier specification.

The Air Ministry perhaps understandably was not interested in Avro’s triplane. Handley Page was rejected, allegedly because of a breach of the Official Secrets Act! The other three types were ordered as prototypes, three of the Fairey, two of the Blackburn and one of the Hawker.

Considering Hawker’s later record with elegant, beautifully proportioned naval aircraft, the Hedgehog can be considered dumpy and awkward. That it was somewhat less lumpen than the three types intended for replacement is hardly to Hawker’s credit. It’s unclear whose hand penned the machine’s stubby lines, as it was initiated around the time that Captain Thompson was handing over the reins of Chief Designer to WG Carter. It’s also unclear who decided to name the type after a distinctly land-bound and unthreatening animal. (The RAF-wide naming policy at the time seemed to be to name fighters after birds, bombers after towns and cities, and reconnaissance aircraft after animals. It’s not apparent how the Blackburn Blackburn managed to buck this trend, but as it was initially given the capability to act as a torpedo bomber, perhaps this enabled the company to make an argument).

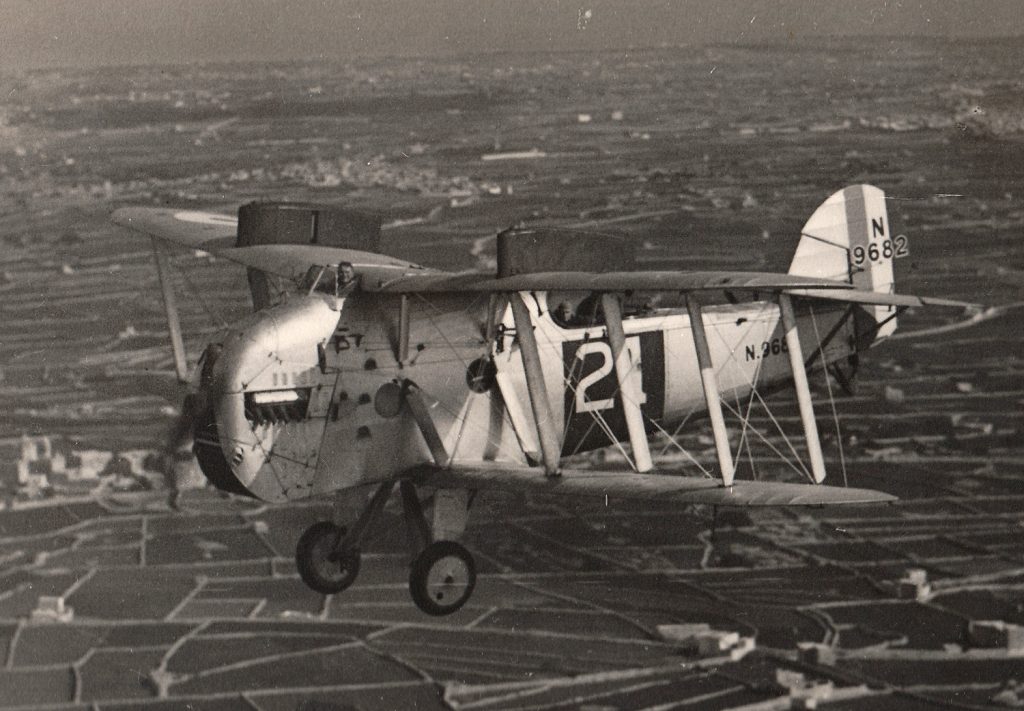

The Hedgehog was a rather bulky zero-stagger single-bay biplane built in an all-wood structure, with a wide-track undercarriage and something of a profusion of struts around the centre section. It was later rendered even more clumsy with modifications including a multi-link oleo undercarriage and a large fuel tank of thick aerofoil form set atop the upper wing centre-section. The one concession to modernity was the capability for the ailerons to be lowered in concert to increase the camber of the wing. Even this was hardly the ‘novel feature’ described by Francis K. Mason in Hawker Aircraft Since 1920 (Putnam, 3rd edition 1991), as Fairey had been using a similar system since 1916, and even the unpromising Blackburd of 1918 had drooping ‘flaperons’, albeit of a simpler type.

Nevertheless the Hedgehog was found to be much more spritely in the air than its unprepossessing appearance suggested, when the sole Hedgehog, N187, first flew in September 1924. The Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment at Martlesham reported that the Hedgehog was ‘exceptionally light and pleasant to handle in the air’, and photographs in Flight of the Hedgehog being thrown around by PWS ‘George’ Bulman seem to bear that out. It also had remarkably docile handling around the stall.

Still, almost unbelievably, the Hedgehog had an inferior performance to the Blackburn Blackburn in some respects, with a slightly lower top speed and significantly lower endurance, and only a marginally better service ceiling and climb.

A Blackburn Blackburn, one of the three types the Hedgehog was intended to replace

The Hedgehog and Airedale were somewhat better than the ponderous Bison and the antiquated Panther, but not the Blackburn. The Fairey was some 10-12mph faster than those two machines, and with a rather better climb (13.4 minutes to 10,000ft compared with 24 minutes for the Hedgehog) but the Air Ministry concluded that the machines designed to 37/22 did not offer a worthwhile improvement over the aircraft already in service and cancelled the specification. The failure to advance on the bulky Blackburn must have come as some disappointment to the Air Ministry and the Fleet Air Arm, but they did not have too long to wait. Fairey developed the Ferret/IIIE into the Napier Lion-powered IIIF, which successfully replaced all the previous types and served in the front line from 1927 to 1936. Its replacement was a further evolved IIIF, the Seal, this time with the air-cooled engine that the Fleet Air Arm had wanted since the early 1920s.

Hawker aircraft in the early 1920s tended to fall into one of two extremes – pleasant and easy to fly, and comfortable, but with a disappointing performance, or high performance but impractical and flawed in their handling. The arrival of Sydney Camm in the Hawker design team while the Hedgehog was under development put an end to those compromises. The next generation of Hawker naval aircraft would be all-round performers. The Hedgehog though remains a footnote in that company’s long relationship with the Fleet Air Arm. Its fate was as obscure as its career. It was retained for experimental use in 1925, but details are sketchy. It apparently tested wings of novel Eiffel 385 section and was then converted to a floatplane but was written off that year in unclear circumstances.