From the earliest days of naval aviation in the UK, aircraft types were developed which, for one reason or another, did not enter service. These ranged from private ventures offered to the Admiralty on spec to aircraft formally requested through an official requirement. Some of these were short-lived, others tested for years through multiple evolutions with a range of powerplants and other differences. Some prototypes lost out to other, more successful types, sometimes they were developed into successful machines, and sometimes the whole requirement was scrapped and all proposed types abandoned. This series aims to give an overview of the prototypes considered and ultimately rejected for naval aviation.

The first aircraft to be considered is the Blackburn Blackburd, a torpedo bomber conceived during the First World War and representing the wave of aircraft that bridged the wartime and interwar periods. The Blackburd appeared as a result of a convoluted and rapidly changing system of specifications. It was originally requested in 1917, bizarrely via a specification issued for a seaplane, N.1B (KJ Meekoms & EB Morgan, The British Aircraft Specifications File, Air Britain 1995). This requirement was for a single-seat seaplane to replace the Sopwith Baby for coastal patrol, anti-submarine and anti-zeppelin work. The Blackburd, however, along with its rival the Short Shirl, was actually intended a replacement for the Sopwith Cuckoo ship-based landplane (i.e. with wheeled undercarriage) torpedo bomber. When the Royal Air Force and Air Ministry were created in 1918, the Admiralty and Royal Flying Corps specification systems were merged and the Blackburd and Shirl were given their own requirement separate to the N.1B seaplanes, specification Type XXII.

The Cuckoo had been the first dedicated torpedo aircraft designed for launching from an aircraft carrier, and was adapted from the Sopwith B.1 bomber design in response to a request from the Admiralty in 1916. Such was the rapidity of naval aircraft development that in 1917, the Admiralty was considering the replacement of an aircraft, with a significantly more capable machine, in a class that did not even exist a year before. By that year, the first proper aircraft carrier, HMS Furious, was engaged in landing and alighting tests, and the next generation of continuous deck aircraft carriers had already been initiated.

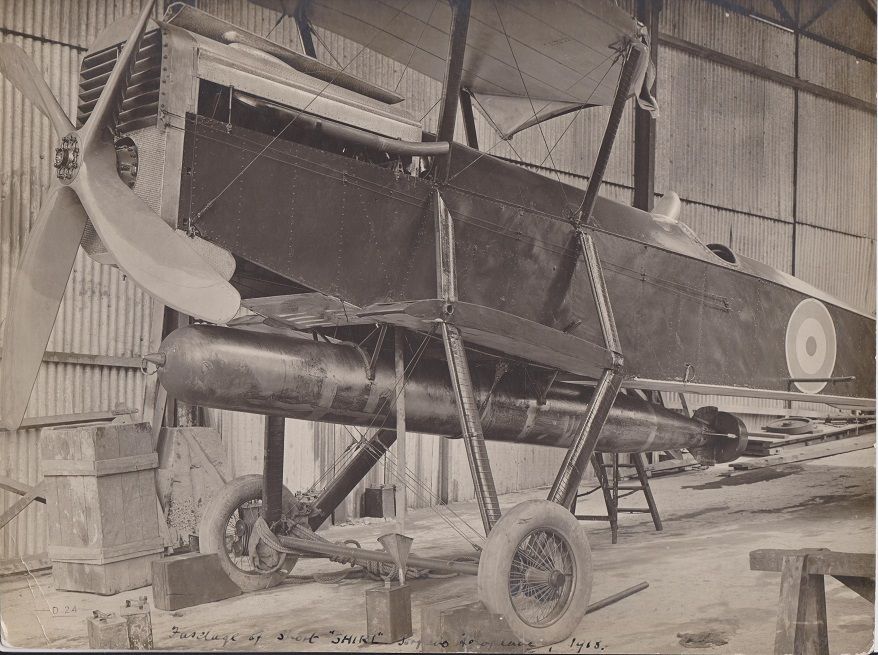

The Cuckoo was a capable aeroplane, its main shortcoming being the unreliable Sunbeam Arab powerplant. It was manoeuvrable and had a decent performance for its size and power. It had, however, been developed to carry a 1,000lb torpedo. In 1916 this was an almost unheard of load for a single-engined aircraft, but nevertheless the Admiralty was unsatisfied. The chief problem with the 1,000lb projectile was that it could not be relied upon to inflict fatal damage on the most heavily armoured warships. The difficulty of dealing a death blow to a dreadnought battleship with guns alone had been highlighted during the Battle of Jutland, as had their the vulnerability to torpedoes. The Royal Navy , by 1917, was increasingly convinced that torpedoes dropped by aircraft could alter the tide of fleet engagements. An aircraft that could carry the capital ship-killing Mk.VIII torpedo weighing in at 1,423lb would increase the Royal Navy’s hitting power significantly. The Blackburd and Shirl were created to fulfil this role, and three prototypes of each were ordered. Both were to be single-seaters (no aircraft at the time could hope to carry both a torpedo and a second crewmember) powered by the 385hp Rolls Royce Eagle, providing significantly more power than the Cuckoo’s 212hp Sunbeam, albeit at a greater weight.

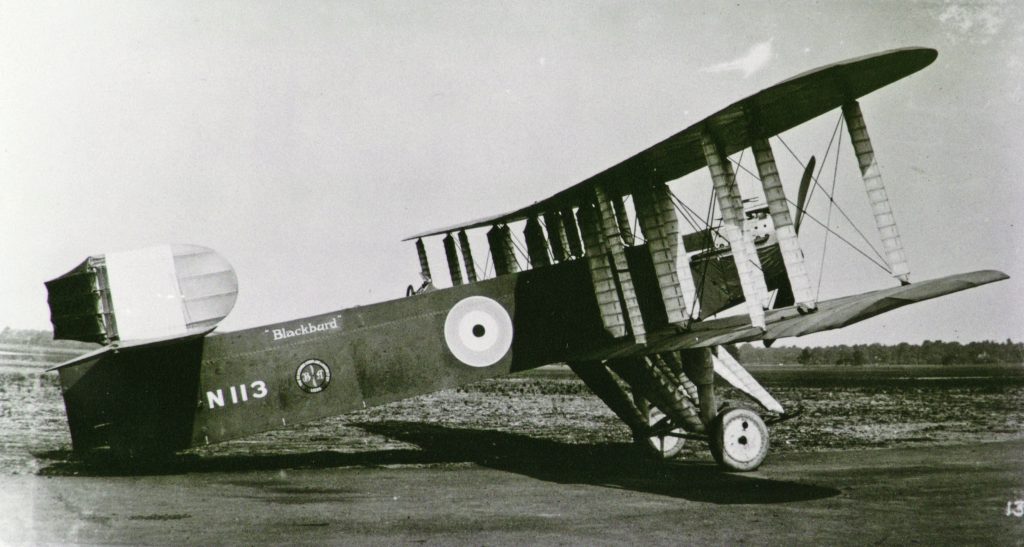

First prototype Blackburn Blackburd N113 with original rudder and smaller radiator (author’s collection)

Due to the need to create a single-engined aircraft that could lift and deliver the enormous Mk.VIII torpedo, Blackburn’s designer, the former Admiralty man Harris Booth, focused on creating a structure of high strength and low weight. Many design strategies were pursued to keep structure weight to an absolute minimum. At the same time, the exigencies of wartime production were prioritised in the Blackburd’s design. The most obvious manifestation of this was in the ungainly fuselage, of constant depth along its entire length and constant width for the forward two thirds. The deep box structure this formed had a high strength-weight ratio and simplified construction, with most of the component members, such as the longerons and spacers, being common items. The wings were similarly simple, of constant chord and section and designed around common components.

The interplane struts demonstrated how maximum attention was paid to weight saving. Blackburn developed a steel tube faired with plywood formers and doped fabric – a structure that was both lighter and aerodynamically more efficient than conventional solid spruce struts. While this involved more processes than the conventional strut, the component parts could be mass produced for assembly easily. The controls were similarly simple and optimised for light weight – the ailerons, for example, only had a ‘pull’ function which deflected the control surface downward, after which it was returned to a neutral position by a bungee cord. The ailerons also acted as flaps, with a separate control causing them to droop – the obvious drawback being that once the ‘flaperons’ were dropped to their full extent, the pilot had no means of lateral control! Its value was nonetheless demonstrated when, according to AJ Jackson in Blackburn Aircraft since 1909 (Putnam, 1968), the first prototype Blackburd ‘unstuck’ in a third of the distance than without the flaps depressed.

The Blackburd’s undercarriage is also worthy of note. From 1917, the HMS Furious and the experimental establishment on the Isle of Grain had carried out a series of experiments with skid undercarriage for deck landing. In line with the weight-saving and simplifying approach Harris had taken with the aircraft, the undercarriage was a simple split skid system. Wheels were fitted on a jettisonable axle purely for take-off. The cockpit was placed unusually far aft, almost halfway between the wings and the tail, which must have afforded the pilot a reasonable view downward but a very poor view over the nose.

The result of Blackburn’s unconventional approach was an aircraft whose ugliness remained largely unsurpassed during the biplane era. The angular appearance of the aircraft was striking, and not in a good way. The adage ‘if it looks right, it will fly right’ suggested that the Blackburd risked being very wrong indeed.

As it happened, the Blackburd was indeed unpleasant to fly. It was stable laterally (which was just as well given the total lack of lateral control with the flaps extended) but unstable longitudinally and directionally. It was nose-heavy in all conditions of flight, and very tiring for the pilot to constantly fight the control loads that this imparted. The rudder provided insufficient control authority. Nevertheless, Blackburn’s test pilot RW Kenworthy was able to carry out a series of test flights in the first prototype N113 in June 1918, involving dummy torpedo drops and wheel jettisoning.

Blackburn Blackburd second prototype N114 with larger rudder and deeper radiator, with floats under the wings (author’s collection)

The second prototype, N114, completed in August 1918, incorporated some developments, partly in response to the shortcomings of the first machine. The rudder was redesigned and enlarged, the undercarriage was modified to incorporate ‘hydrovanes’ to assist with ditching at sea, and small floats were attached to the outer wings. A larger radiator, suitable for tropical climates, was also fitted. This aircraft underwent service tests at East Fortune and performance tests at the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment at Martlesham Heath. Over this period the Blackburd was compared with the slightly less inelegant Shirl and overall found inferior, although the Blackburd was slightly faster and significantly lighter. In truth, neither machine was really satisfactory, being much more ungainly and sluggish than the Cuckoo. With the end of WW1, the need for a capital ship-killing aeroplane was less urgent, and the Navy and RAF could concentrate on developing the still-new science of carrier air strike with the Cuckoo.

Short Shirl, showing clearly the undercarriage that had to be jettisoned before the torpedo could be launched (author’s collection)

Within a few years, the development of more powerful engines (such as the Napier Lion) and the tentative adoption of metal structures, of which Blackburn was a pioneer, would allow more practical aeroplanes capable of carrying the larger torpedo. This allowed Blackburn a second bite at the cherry, with the Swift, developed for the RN as the Dart – an aircraft that, while hardly beautiful, was much better proportioned than the hideous Blackburd. It was also a success, equipping the new Fleet Air Arm well into the 1930s and enjoying some export success. The Blackburd, while unsuccessful in itself, had taught Blackburn a very great deal – many of the Blackburd’s innovations in common components (each of the four mainplanes was identical, for example) and high strength-weight ratio structures were carried over, in a rather more elegant package. Meanwhile, Blackburn dealt with the Blackburd’s appalling forward view by giving the Dart/Swift a raised cockpit and sloping nose. Blackburn were the sole providers of torpedo aircraft to the Fleet Air Arm from 1922 to 1935, a fact that can in part be attributed to the lessons learned with the Blackburd, positive and negative.