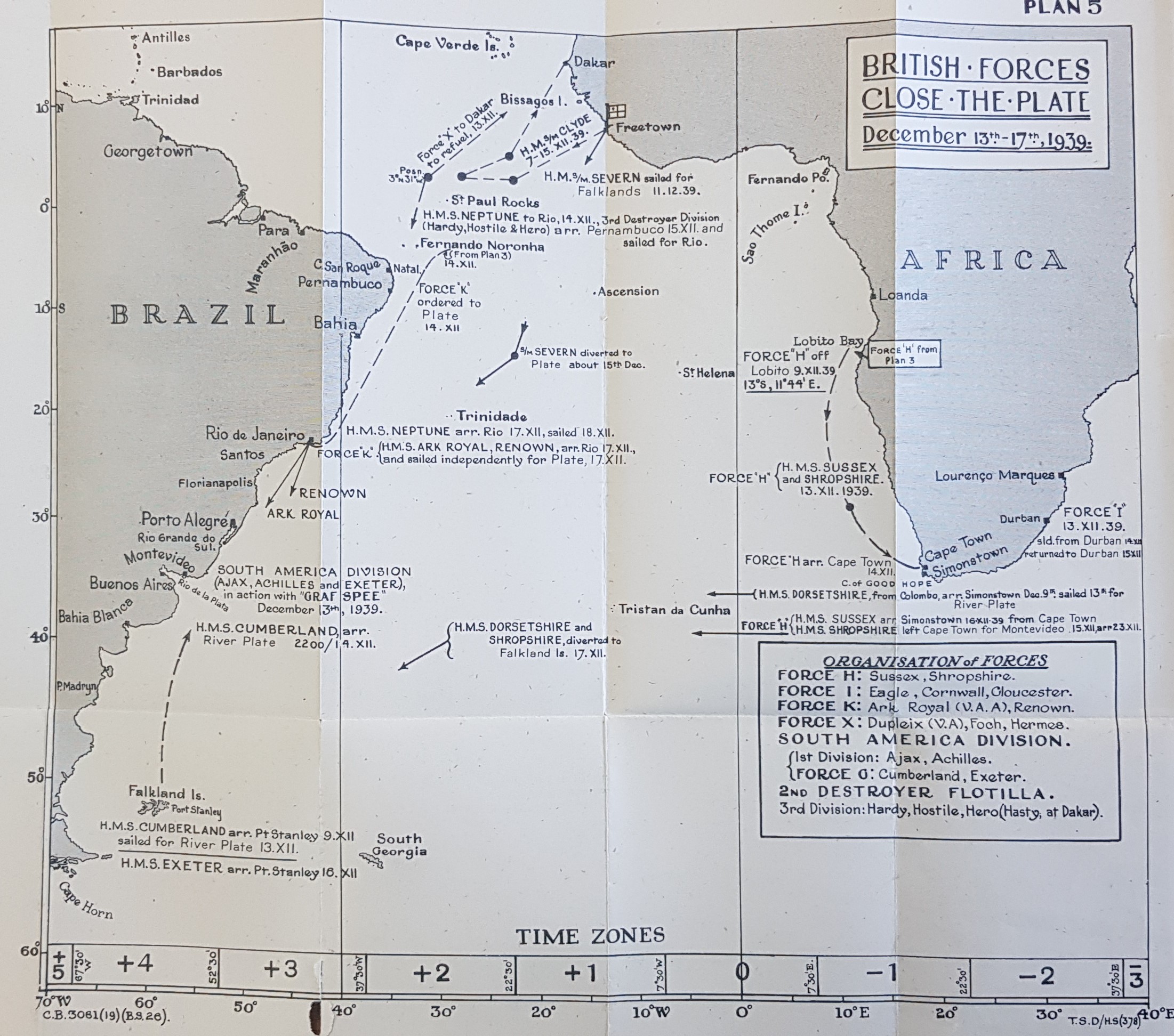

From ADM 186/794 – the forces closing the River Plate

The time for the Graf Spee in Montevideo is defined in many ways by the Hague Convention (XIII) which concerned the Rights and Duties of Neutral Powers in Naval War and had been agreed prior to World War I on the 18th October 1907. Specifically the following articles1:

Art. 12. In the absence of special provisions to the contrary in the legislation of a neutral Power, belligerent war-ships are not permitted to remain in the ports, roadsteads, or territorial waters of the said Power for more than twenty-four hours, except in the cases covered by the present Convention.

Art. 14. A belligerent war-ship may not prolong its stay in a neutral port beyond the permissible time except on account of damage or stress of weather. It must depart as soon as the cause of the delay is at an end.

The regulations as to the question of the length of time which these vessels may remain in neutral ports, roadsteads, or waters, do not apply to war-ships devoted exclusively to religious, scientific, or philanthropic purposes.

Art. 16. When war-ships belonging to both belligerents are present simultaneously in a neutral port or roadstead, a period of not less than twenty-four hours must elapse between the departure of the ship belonging to one belligerent and the departure of the ship belonging to the other.

The order of departure is determined by the order of arrival, unless the ship which arrived first is so circumstanced that an extension of its stay is permissible.

A belligerent war-ship may not leave a neutral port or roadstead until twenty-four hours after the departure of a merchant ship flying the flag of its adversary.

Art. 17. In neutral ports and roadsteads belligerent war-ships may only carry out such repairs as are absolutely necessary to render them seaworthy, and may not add in any manner whatsoever to their fighting force. The local authorities of the neutral Power shall decide what repairs are necessary, and these must be carried out with the least possible delay.

These are the talking points which Millington-Drake, Langsdorff, Dr Guani and everyone else involved would be referring to them constantly. Art 17 is the most critical, especially after the report concludes that 72hrs is all they need – after all the damage is listed as2:

- Fifteen holes on the starboard side and twelve on the port – including large & small

- Fire-fighting apparatus damaged – but not material to seaworthiness

- Cracks claimed to be on the stern by the Germans were not observed

- A shell burst had destroyed a lot of the galley and laundry

- Repairs necessary for the drinking water boiler…

- When asked if there had been any damage to the engines, the Commander apparently replied “these were below the armoured deck and had suffered nothing, so were not inspected.”

What is interesting is that it’s obvious issues must have happened with the engines, especially considering what is admitted in publications by the crew post war, whether it’s down to the wear & tare of the long distance operations, the battle or a combination of the two – but Langsdorff did not show them to the inspectors. This might have made the difference in the debate of seaworthiness and it’s notably in contrast to the stories of HMS Glasgow & HMS Carnarvon of WWI, where the Royal Navy was far more open in allowing Brazilian inspection teams to look around the ships. Whether this is because there really wasn’t many issues down there (in which case what is the harm of looking; surely that would add to the magnificence of the ship, to have survived so much with so little damage) or because there was actually a significant amount of damage (which would revealed the ‘truth’, but also could have given him a chance for a longer stay).

The reality was it was unlikely that the Graf Spee was ever going to get the 30 days Langsdorff was asking for, even if Millington-Drake had not been as good at diplomacy and as popular figure in Uruguay as he was. The big what if is of course, if Langsdorff had realised support was going to be so lacking within this nation, would he have gone to Argentina? Probably yes, would they have granted him more time, possibly – but the same factors would have affected them as Uraguay. There might be a significant local German expat community, but the British have been there a long time, have deep connections, have a benevolent America supporting them and are the ones who control the sea – antagonising them in favour of a power who cannot help you, would not be good politics. The aside from the Glasgow & Carnarvon story is that yes this takes place after the Battle of Coronel, but no one in South America then doubted that the British were still the major sea power providing the securing upon which global trade depended. This meant that in realpolitik terms it made sense to be as helpful as possible, just as with the Graf Spee it made sense to be very letter of law.

Either way if Langsdorff had secured 30 days for the Graf Spee, the question becomes would she have survived that long? HMS Ark Royal was coming and as a ship in a neutral harbour, Graf Spee displayed a lot of lights at night. The RN would have had the choice, apologise for violating a neutral or take the risk that submarines or other support might show up. If Tsingtao in January of 1939 and the soon to come Asama Maru incident of January 1940 with Japan, especially the Altmark Incident of February 1940 with Norway, demonstrate anything, they show the RN is full committed to the philosophy of “It’s better to ask for forgiveness, than beg for permission”. Would such actions have caused repercussions, probably, but would they have been acceptable? Yes. Especially in light of the German’s own propaganda, by categorising the Battle of the River Plate as a great victory, portraying their ship as hardly damaged, they actually provided the narrative themselves that the British, whether the RN or the Ambassadors of the Foreign Office would have been able to deploy to back up such actions.

As such considering all this, considering the timeline of the Ark Royal the odds that on the 18th of December 1939, whatever the decisions by any parties, the Graf Spee would have been sunk. Whatever the case and whether by her own crew or by the Fleet Air Arm’s Blackburn Skua Dive Bombers of 800 & 803 squadrons supported by the Fairey Swordfish Torpedo Spotter Reconnaissance (the idea of having one airframe for multiple roles did not originate with the F35 program) of 810, 820 & 821 sqns, Graf Spee’s life expectancy was not to be measured in weeks after the 13th of December, day of course, but an argument could be made for hours.

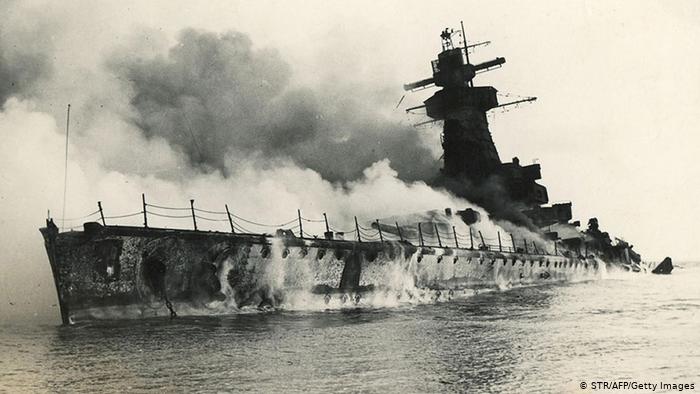

The Admiral Graf Spee, smoking outside Montevideo Harbour – a smouldering tribute to what could have been.

Bibliography

Avameg, Inc, 2012. Arbitration, Mediation, and Conciliation – The Hague peace conferences. [Online]

Available at: http://www.americanforeignrelations.com/A-D/Arbitration-Mediation-and-Conciliation-The-hague-peace-conferences.html

[Accessed 04 March 2012].

Clarke, A., 2014. Sverdlov Class Cruisers, and the Royal Navy’s Response. [Online]

Available at: https://globalmaritimehistory.com/sverdlov_class_rn_response/

[Accessed 11 February 2018iii].

Clarke, A., 2018i. Royal Navy Cruisers (1): HMS Exeter, Atlantic to Asia!. [Online]

Available at: https://globalmaritimehistory.com/royal-navy-cruisers-1-hms-exeter-atlantic-asia/

[Accessed 30 March 2018].

Friedman, N., 2010. British Cruisers; Two World Wars and After. London: Seaforth Publishing.

Hore, P., 2018. Henry Harwood; Hero of the River Plate. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing.

International Peace Conference. (1st : 1899 : Hague, Netherlands); Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Division of International Law; International Peace Conference. (2nd : 1907 : Hague, Netherlands); Scott, James Brown, 1866-1943, 2014. The Hague conventions and declarations of 1899 and 1907, accompanied by tables of signatures, ratifications and adhesions of the various powers, and texts of reservations; edited by James Brown Scott, director. [Online]

Available at: https://archive.org/details/hagueconventions00inteuoft/page/208

[Accessed 18 November 2019].

Konstam, A., 2015. Commonwealth Cruisers 1939-45. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd.

Millington-Drake, E., 1965. The Drama of Graf Spee and the Battle of the Plate. London: Peter Davies.

Morris, D., 1987. Cruisers of the Royal and Commonwealth Navies. 1st ed. Liskeard: Maritime Books.

Scott, J. B., 2008. Source taken from a Series of Lectures given in 1908: Peace Conference at the Hague 1899; Report of Captain Mahan to the United States Commission to the International Conference at the Hague, Regarding the Work of the Second Committee of the Conference.. [Online]

Available at: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/hag99-07.asp

[Accessed 4 March 2012].

TNA – ADM 116/4109, 1940. Battle of the River Plate: reports from Admiral Commanding and from HM Ships Ajax, Achilles and Exeter.. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew).

TNA – ADM 116/4320, 1941. Battle of the River Plate: British views on German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee in Montevideo harbour; visits to South America by HMS Ajax and HMS Achilles. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew).

TNA – ADM 116/4470, 1940. Battle of the River Plate: messages and Foreign Office telegrams. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew).

TNA – ADM 186/794, 1944. Battle Summary No 26: The Chase & Destruction of the “Graff Spee” 1939. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

Whitley, M. J., 1996. Cruisers of World War Two; An International Encyclopedia. London: Arms and Armour Press.

- International Peace Conference. (1st : 1899 : Hague, Netherlands); Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Division of International Law; International Peace Conference. (2nd : 1907 : Hague, Netherlands); Scott, James Brown, 1866-1943, 2014. The Hague conventions and declarations of 1899 and 1907, accompanied by tables of signatures, ratifications and adhesions of the various powers, and texts of reservations; edited by James Brown Scott, director. [Online] Available at: https://archive.org/details/hagueconventions00inteuoft/page/208 [Accessed 18 November 2019]

- Millington-Drake (1964), The Drama of the Graf Spee and the Battle of the Plate, p.306