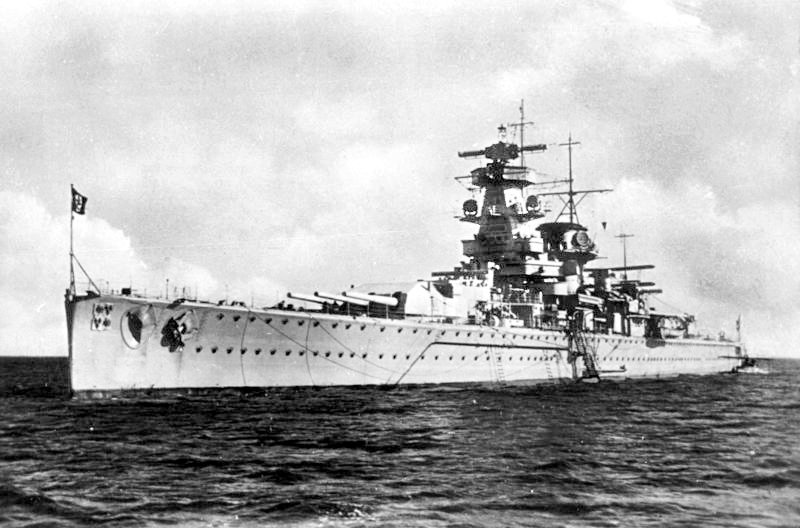

The Admiral Graf Spee

On the 21st of August 1939 the heavy cruiser, usually described as a ‘Pocket-Battleship’, more accurately termed a Panzerschiff or surface raider, Admiral Graf Spee leaves Wilhelmshaven harbour headed by circuitous route for the South Atlantic. This was the culmination of many years of geo-strategy, of various German officers and politicians analysing World War I and coming to the conclusion that a direct confrontation strategy with the Royal Navy wouldn’t work. What they needed to do was pursue an offset strategy as it would be called today, a strategy of economic warfare. The idea was to use surface raiders to draw off RN’s escorts, so that the submarine force could massacre the North Atlantic merchant ships, strangle Britain of supplies and force some form of surrender. Many of the senior officers doubted that such a circumstance would come to pass, but still it was the best chance they had and the best case they could make for a balanced navy.

The Admiral Graf Spee was a Deutschland Class cruiser, they were heavily armed for their displacement of 16,280t (fully loaded); carrying six 11in guns in two triple turrets, eight 5.9in guns in single turrets, eight 21in torpedo tubes and ten 2cm anti-aircraft guns. An outfitting which befitted ships which were replacing pre-dreadnought battleships in service with the German Navy; the Reichsmarine 1919-35, Kriegsmarine 1935-45. They were built to be surface raiders, to pillage global trade, for that it wasn’t just weaponry which mattered. The class also came with a top speed of 28.5knots, a range of 16,300nmi at ~18knots and a pair of Arado Ar 196 seaplanes – all the sorts of for the time conventional things which would make a great surface raider. They didn’t stop there though, one of the most important thing though that she carried, was one of the first working fitted types of the SEEKAT radar, enabling her to find and fix targets in any weather. Ships though are much more than just equipment collected in a metal box, they are their crew, they are their culture, they are their captain, therefore the true measure of their capabilities are a fusion of all of this.

The Admiral Graf Spee, sometimes referred to as the Graf Spee, was named for Admiral Von Spee who had managed, whilst trying to return his Pacific squadron of pre-dreadnought era cruisers to Germany during WWI, to win success at the Battle of Coronel, as well as conduct of several raids and seizures of ships. Arguably the most successful officer of the Kaiserliche Marine (German Navy 1871-1919), his reputation was as one of an innovator, a problem solver, who did his duty in the face of insurmountable odds – which eventually, at the Battle of the Falklands, would destroy him, his force and his two sons who’d been serving in other ships of his squadron. By coincidence of fate, Captain Langsdorff, the commander of the Graf Spee on its mission to the South Atlantic, had been a neighbour of the Spee’s whilst growing up – they’d been a reason he had joined the navy in the first place.

Hans Wilhelm Langsdorff was a proud officer, a good one by the standards of any navy, not just the Kaiserliche Marine he’d joined in 1912, the Reichsmarine he’d served most of his career or the Kriegsmarine he found himself one of the leading personalities off in 1939. He spent much of his career as a torpedo specialist, but his first command was a small vessel the purpose of which was to guide submarines back through their own minefields. This command had caused him to have trouble initially, as he was required to not display a light, so unsurprisingly in the dark at night he couldn’t find the submarines and they couldn’t find him – eventually after speaking with a senior petty officer, he realised whilst the rules forbade a white light, they did not mention a blue. Thereafter he displayed a blue light and every submarine they did find to bring back safely. Such a meticulous attention to rules combined with a creative approach to them when necessary would be the hallmarks of his career and get him to the command of the Graf Spee.

During the course of her mission, the Graf Spee sank nine merchant ships, the Clement, the Newton Beech, the Ashlea, the Hunstman, the Trevanion, the Africa Shell, the Doric Star, the Tairoa, and the Streonshalh. This though is a very simplistic approach to take when evaluating the impact of a surface raider – after all when we consider the effects of any other form of warfare we don’t just count the numbers killed. So for a surface raider we have to consider, but will never really know, how many journeys were lengthened or even cancelled because of her actions. This is before considering the wider psychological impact she achieved with successes in a part of the world the RN and the British public to extent considered safe, if not actually ‘theirs’ in a way. All this is an effect which the Graf Spee achieved with its cruiser, far more so than its sister the soon to be renamed Deutschland did in the North Atlantic.

It could also be considered from the pre-war planning perspective, with the RN and French Navy resourcing eight groups around the Atlantic to hunt her down. What impact could these vessels have had if they had been instead deployed for other operations – the Northern Barrier perhaps or maybe strike operations in support of land forces? That can’t be really know. What is known is that these forces contained four aircraft carriers, including the newest of the RN’s prized (and much requested) fleet carriers, the strike carrier HMS Ark Royal; HMS Renown a British Battlecruiser, two French Battleships, the Dunkerque and Strasbourg; along with twelve cruisers in addition to the four that served under the command of Commodore Henry Harwood in Force G/South America Division. This was a major force commitment, but with Italy not joining the war till June 1940, Japan waiting till December 1941 – the German navy was alone and frankly even these commitments were not a strain on the RN, let alone the cumulative allied force.

Bibliography

Clarke, A., 2014. Sverdlov Class Cruisers, and the Royal Navy’s Response. [Online]

Available at: https://globalmaritimehistory.com/sverdlov_class_rn_response/

[Accessed 11 February 2018].

Clarke, A., 2018. Royal Navy Cruisers (1): HMS Exeter, Atlantic to Asia!. [Online]

Available at: https://globalmaritimehistory.com/royal-navy-cruisers-1-hms-exeter-atlantic-asia/

[Accessed 30 March 2018].

Friedman, N., 2010. British Cruisers; Two World Wars and After. London: Seaforth Publishing.

Hore, P., 2018. Henry Harwood; Hero of the River Plate. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing.

Konstam, A., 2015. Commonwealth Cruisers 1939-45. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd.

Millington-Drake, E., 1965. The Drama of GrafSpee and the Battle of the Plate. London: Peter Davies.

Morris, D., 1987. Cruisers of the Royal and Commonwealth Navies. 1st ed. Liskeard: Maritime Books.

TNA – ADM 116/4109, 1940. Battle of the River Plate: reports from Admiral Commanding and from HM Ships Ajax, Achilles and Exeter.. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew).

TNA – ADM 116/4320, 1941. Battle of the River Plate: British views on German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee in Montevideo harbour; visits to South America by HMS Ajax and HMS Achilles. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew).

TNA – ADM 116/4470, 1940. Battle of the River Plate: messages and Foreign Office telegrams. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew).

TNA – ADM 186/794, 1944. Battle Summary No 26: The Chase & Destruction of the “Graff Spee” 1939. London: United Kingdon National Archives(Kew).

Whitley, M. J., 1996. Cruisers of World War Two; An International Encyclopedia. London: Arms and Armour Press.

The Admiral Graf Spee