Matt describes his recent visit to HMS Caroline, one of the last remaining warships from the First World War.

Against the UK’s recent patchy background of preserving historic warships (with the loss of HMS Plymouth to the scrapman’s torch and HMS Illustrious almost certain to go the same way), the restoration of the WW1 light cruiser HMS Caroline as a museum ship is a genuine success story. Caroline, as with many preserved ships, owes her survival more to usefulness in a secondary role rather than her historic status. Until 2011, Caroline acted as the headquarters and training establishment of the Royal Navy Reserve at Belfast, an unglamorous role that secured her future – and at least less lowly an occupation than those endured by HMS Warrior and Monitor M33, which both acted as oil jetties for a time. (Other preserved warships such as HMS Unicorn and HMS Trincomalee spent time as training or accommodation hulks).

That said, Caroline’s historic status is not in any doubt today. She is one of only three Royal Navy ships to survive, and of the three is the only one to have served with the Grand Fleet. Most importantly, she is the only surviving vessel (from either side) to have taken part in the Battle of Jutland, the critical clash of battle fleets that took place in 1916. It was the biggest naval battle of the war, the biggest naval gunnery battle ever, and a turning point in the war at sea. As such, the preservation of Caroline and her opening as a museum ship is a crucial recognition of the importance of the battle in its centenary year – something that has tended to be overshadowed by controversies over the management and outcome of the battle, a clash of personalities between the two main British commanders, and the vast campaigns on land that came shortly after.

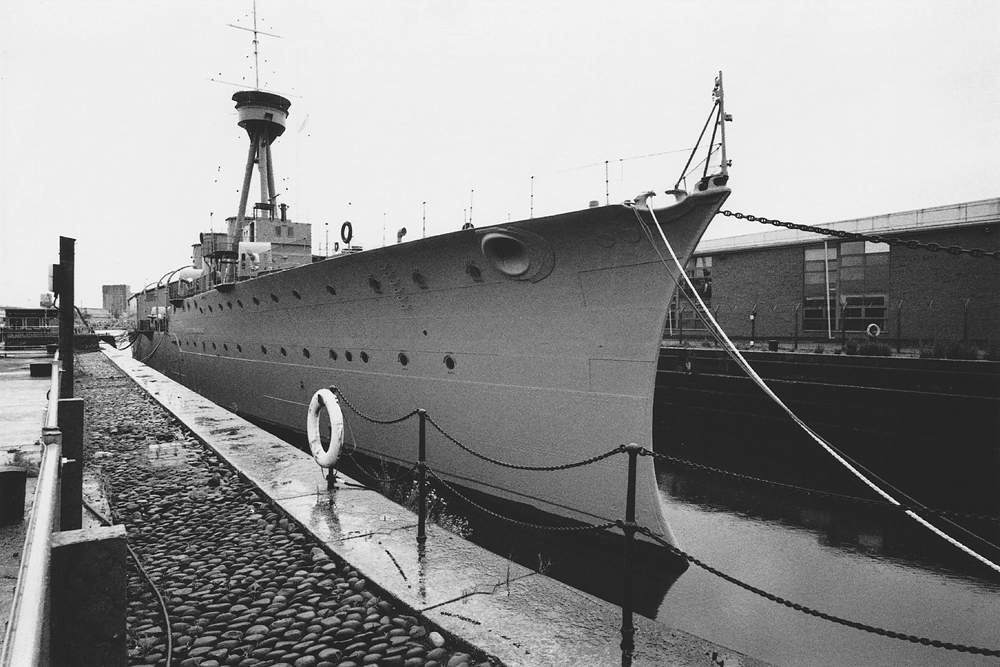

I visited HMS Caroline in December 2014, after the declaration that she would be restored, but before most of the work had begun. Caroline had been afloat for most of her life, and as a working RN vessel had been kept in sound and workmanlike, if inelegant, condition. A large drill-hall had been built on her midships shortly after she was re-tasked as an admin ship. Some time after that, another structure had been built over the aft superstructure (originally the captain’s accommodation) which was, frankly, ugly, and really affected the cruiser’s looks. Naturally, all armament had been removed long since. In 2014, she was rust-streaked and tatty. Promisingly, work to put things right was clearly beginning – a framework was being erected over the foredeck, which, it later turned out, would carry a canopy beneath which the old, rotten deck planks would be removed and new decking fitted.

Much of the work took place out of sight. One of the biggest jobs was the removal of asbestos, which peppered the ship. She was built, and spent much of her active life, before the dangers of asbestos were known, and not only was a fair amount included in her construction, more was added over the years. A myriad of other, smaller but no less important, tasks, such as removing a rifle range and, mercifully, that horrible shed aft) had to be accomplished before the vessel could be opened to the public for the anniversary, then only 18 months away. That all this work was completed in this time, I found nothing short of astonishing. Wisely, the decision was taken to carry out the restoration in phases. Phase 1 would see the major internal work completed, cosmetic restoration, fitting of replica armament, and lifts to allow some disabled access. This would see Caroline reopened for the Jutland anniversary, before being closed again in October for dry docking and some work to the external hull. In time, it is hoped that further internal spaces can be opened up and made accessible. Even with the drill hall still in place, the external appearance gives a good impression of the Caroline’s appearance as a warship.

I visited Caroline again in June 2016, and found the results of the restoration to be extremely impressive. Even though this was the ‘Phase 1’ restoration, nothing about the museum ship felt incomplete or rushed. I suspect most of the successful museum ships in the UK are those that benefit from additional ‘infrastructure’ such as the vessels based at the Portsmouth and Chatham dockyards. Caroline should benefit in this regard from being part of Belfast’s Titanic Quarter, adjacent to the Titanic museum, SS Nomadic, and the historic Harland and Wolff shipyard (with its distinctive Krupp gantry cranes Samson and Goliath). Caroline’s berth in the Alexandra Graving Dock lends a very historic feel in its own right, in keeping with Belfast’s maritime history.

My initial impression was just how original and authentic Caroline feels. Some restored warships are, by necessity, almost brand-new feeling. Stepping aboard HMS Warrior, for example, feels as though the visitor has entered the ship moments after fitting out, and before the crew has come aboard. Obviously Warrior was essentially a hulk before her restoration, so this was unavoidable, but I was delighted to see that Caroline has in no way been over-restored. The years of service are apparent in the layers of paint, the patina of all the surfaces. Many of the original signs and fittings are still in place. Spaces such as the captain’s cabins, the wardroom, washrooms and messes have been re-appointed to resemble their appearance in WW1, and again these feel very authentic. Some of the cabins are labelled according to the personnel who occupied them during WW1, and information is given about these individuals, nicely personalising the experience.

Approximately two full decks are open to the public, plus the forecastle, navigating bridge and engine rooms. Some of these areas, as already mentioned, have been reconstructed to their WW1 appearance. The engine rooms, amazingly still containing their original four Parsons turbines, are largely complete, and visual and sound effects have been added to simulate the experience of the ship steaming at full power.

Other spaces, such as the drill-hall and some of the areas that had been converted to classrooms (and were therefore difficult to put back to their wartime appearance) have been given over to educational and informative facilities. These include a film showing a reconstruction of the Battle of Jutland cleverly projected directly onto the inside wall of the former drill hall. A ‘signal school’ and ‘torpedo school’ use interactive tools to teach about WW1 era communications and weaponry. The ‘dazzle zone’ includes an exhibition about the development and evolution of WW1 dazzle camouflage (providing a nice link with both the other WW1 warship survivors, HMS President 1918 and HM Monitor M33, which both wear dazzle schemes, the latter historical, the former conceptual).

Where the original fittings are still in place, such as on the navigating bridge where the compass binnacle and telegraphs remain, the effect is extraordinarily original. Where some replacement fittings have had to be sourced, such as the 6” and 4” guns, it is slightly less so – the guns are replicas and lack some of the detail of the original articles (as can be seen on Monitor M33, for example). This is, nevertheless, a good way of telling what is original and what is new at a glance without spoiling the overall effect.

What is open the public is extensive, and provides a good few hours’ occupation, even without taking advantage of the cafe in the forward mess deck. Naturally though, a number of spaces are not yet accessible, particularly those deeper in the vessel such as the conning tower, tiller flat (which still includes the original wheels for manual steering) and the boiler rooms. A ‘virtual access suite’ in the forecastle allows the visitor to explore these areas through videos, 3D renderings and audio commentary. All parts of the ship that are accessible to the public are also wheelchair accessible, apart from the engine rooms and the upper navigating bridge. Two lifts have been fitted, and these are remarkably unobtrusive.

Tying the whole experience together is the audio guide, one of the best I’ve seen for this kind of exhibit. Each visitor is given a set of headphones and a small device with a push button. Throughout the vessel, small, unobtrusive infra-red sensors have been placed, and pushing the audio guide button in the presence of these triggers information about the subject, including extracts from crewmembers’ diaries, the ship’s log etc. In this way, the visitor can pick and choose which parts of the guide they want to access, and take the self-guided tour at their own pace.

HMS Caroline is definitely one of the crown jewels of the National Museum of the Royal Navy, and a great (and much needed) addition to the preserved warship sector in the UK. A visit is thoroughly recommended, and I look forward to going back after further phases of the restoration have been carried out.

An interesting account of a welcome addition to the UK’s small fleet of historic ships. I’ve been following the Caroline story at a distance ever since I picked up on it on Airminded a few years ago. I’ve also just come back from a trip to Poland, where I took opportunity to go round ORP Blyskawica at Gdynia.

Definitely recommended for those who can get to see her, Blyskawica is beautifully maintained, although I would have less of her internal space given over to displays that could easily be housed in the Polish Navy Museum which is only a short walk away, and more of it in something like original condition. Officers’ and crew’s quarters, command and control stations, magazines etc have either been gutted or are out of bounds. However, her engine and boiler rooms are a real treat, and the tour route even takes the visitor through one of her boilers, as built by G & J Weir in 1936: ‘When ordering spare parts, quote no B2333.’ Which leads me to wonder whether spares were supplied in the 1950s and 1960s, or fabricated behind the Iron Curtain?

As a fully functioning nerd I must make one critical observation on the picture captions: ‘A replica 4.5″ gun on the Caroline’s starboard waist.’ What! I nearly fell off my chair.

Anyhow, Matt’s little piece has whetted my appetite, and I hope I can get to visit next year.