Dr Joanne Bailey of Oxford Brookes University provides our first discussion on masculinity and the Royal Navy from aspects of her current research. Please click on the images to view them at real size.

My current research, titled A Manly Nation, aims to chart ideals of British manliness from 1750 to 1918. Manliness was a term that contemporaries used and it evoked values that were often rooted in the male body and emotions. These values could be quite similar over time, but shifted as notions about bodies and emotions changed.

Having got as far as identifying the key aspects of manliness that I want to write about I have been struck by the way that some cultural motifs seem to embody many of them. The British sailor is one. Scholars have shown how his changing form was closely related to ideas about national, class, sexual and gender identities. Isaac Land describes how Jack Tar developed into a cultural figure intended to stir patriotic hearts from the 1770s: replete with the qualities of dignity and heroism.i One version of Jack Tar was plain-speaking, independent, patriotic and humorous; popularised by the songwriter Charles Dibdin (1745-1814) who explained in 1803 that he portrayed ‘the character of the British tar[, as] plain, manly, honest, and patriotic’.ii The other Jack Tar was explicitly ‘domesticated’, partly due to the mid eighteenth-century pro-natalist concern to swell the population and make it a fighting force. The sexually promiscuous seaman was provided with a wife and children to emerge as warrior, husband and father, symbolic defender of home and family.iii

My impression is that these were often two distinct imagined sailors. In both Jack Tar was typically manly, but this manliness could change in style as it was adopted for different purposes. The sailor’s tears are a good way to explore this distinction.iv

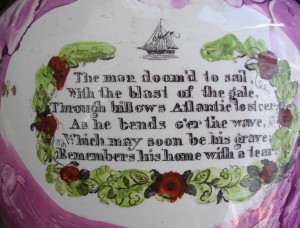

Verse from Lord Byron, The Tear (1806) on jug (probably 1830s):

While the rough-diamond sailor was certainly appealing to some audiences in theatres and songs, I wonder if he retained too much of his rough sea-legs and humour to appeal to other genteel constituencies. Did the Jack Tar who conjoined home, family and tears with courage appeal more to them? Furthermore, was he intended for a largely feminine audience?

The tear-shedding Jack Tar was common in the later Georgian period, personifying a manliness shaped by the cultures of sensibility and domesticity which dominated in turn from around the 1760s to 1860s. The Lady’s Magazine, for example, a magazine for admirers of sensibility, published stories about sailors in the 1780s. These sailors were very much men of feeling. In ‘The Patriotic Parting’ (1782) Mr Townshend, the progeny of a sea-faring family had ‘for some time bridled his rage for glory’ after he married a wealthy lady, due to his ‘Paternal and uxorious affection’. But his ‘love for his country grew predominant over his love as an individual, his love for himself, his wife, or his son’ so that he sought a commission. Ordered to Boston, he served there some time, and on his return home was captured but fortuitously freed by a British privateer. Eventually he returned safe to his native shore. He immediately made his way home to his wife and son. At home he caught up his son and ‘shed over him a deluge of parental tears.’ His wife was soon back in his arms; ‘the summit of all her wishes’. The story’s moral was ‘That the man in a public line of life, who shall not be ready to sacrifice all his interests as an individual, to saving his country when endangered, is neither a good husband, a good father, or what is greater, a good patriot’.v

These domesticated sailors were usually shown expressing their reluctance to part from loving families. The engravings accompanying two of the Lady’s Magazine’s stories show the sailors’ wives and infants standing at the coast waving off the departing sailor. In The Fortunate Affliction the wife and small daughter kneel to pray at a coastal outcrop as a sailing ship departs. In The Patriotic Parting above, the man turns to wave at his wife, and their son sorrowfully buries his head in his mother’s skirts. There is no doubt that manliness was central to these idealised sailors. Mr Townshend was heroic and self-sacrificing. He possessed all the admirable manly attributes, therefore, but in their genteel, sensible form. Crucial to this were his tears.

Although the sailor who shed a tear was a protagonist of stories in women’s periodicals, and a commercial success on decorative ceramics, I’m not sure that he was intended to appeal primarily to a feminine audience. Emotions were physically experienced in very specific ways in the culture of sensibility through the overflow of hearts, tears, and nervous trembling. These were qualities to be nurtured in men as well as women. Manliness in the later Georgian period therefore incorporated feeling, genteel sensitivity and benevolence though they were combined with traditional admirable masculine virtues such as fortitude, stoicism and courage. All were compatible in the correct balance. Courageous naval officers at the start of the nineteenth century, after all, were applauded for their ability to emote, as Nelson reveals.

This was perhaps therefore extending to lower ranks, as suggested in the verse from Lord Byron’s poem The Tear, printed on the lusterware jug above. Perhaps the extent to which the sailor represented a generic manly ideal rather than something specific to seamen or to an model intended to appeal to women was that this poem also has a stanza devoted to a soldier shedding a tear; a type of man who would become a key representative of British manliness by the later nineteenth century.

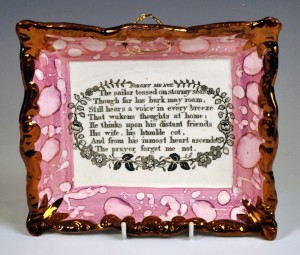

Though sensibility waned in the nineteenth century these tearful manly sailors continued to be important. Numerous ceramics dating from the turn of the eighteenth century through to the mid nineteenth century were decorated with a sailor taking his leave of his wife and small children, and inscribed: ‘The Sailor’s Farewell’. vi Typically these decorative objects also carried moving or moralising verses. Physical distance from home was especially significant, with the sailor’s humble abode, wife and family rooting him in Britain. A verse linking sailor with home is shown on the lusterware plaque below. It comes from The Heart’s Motto: Forget Me Not, written by Bernard Barton (1784–1849). This poem also implored readers to remember a soldier, sculptor, poet, who would all prefer to be remembered than to achieve glory, travel, and fame. Interestingly, however, it is the sailor who was the most domesticated of these men. His thoughts in times of danger were on his wife and cottage.

A Decorative plaque, probably mid-nineteenth century, verse from a poem The Heart’s Motto: Forget Me Not, written by Bernard Barton (1784–1849) a poet from a Quaker family:

Here the manly sailor was integrated into the nineteenth-century cult of domesticity, a cultural concept of great power for much of the century. It had emotional power for men themselves, and not just women. A Wolverhampton Commercial Traveller writing to his prospective wife in 1811, for instance, used a verse on the tar to lead into his reflection on their forthcoming marriage:

The water still breaths in his life’s dying embers

The death wounded tar whose his colours defends

Drops a tear of regret as he dying remembers

How blest was his home with wife children and friends vii

In the popular ballad/song The Sailor’s Tear (1835) the song-writer uses the sailor as the ideal manly Briton, melding feeling, domesticity, and fighting:

He leap’d into the boat

As it lay upon the Strand;

But oh! his heart was far away,

With friends upon the land,

He thought of those he love’d the best,

A wife, and infant dear, —

And feeling fill’d the Sailor’s breast,

The Sailor’s eye, — a tear.

They stood upon the far off cliff,

And wav’d a ‘kerchief white,

And gaz’d upon his gallant bark,

‘Till she was out of sight.

The Sailor cast a look behind

No longer saw them near,

Then rais’d the canvass to his eye,

And wiped away a tear.

Ere long o’er ocean’s blue expanse,

His sturdy bark had sped;

The gallant Sailor from her prow,

Descried a Sail a-head;

And then he rais’d his mighty arm,

For Britain’s foes were near,

Ay then he raised his arm, but not

To wipe away a tear.viii

The potential tensions of attaining apparently incompatible aspects of the manly man – being both a tender husband and father and a fighting man able to perform his duty to the nation – were resolved in this kind of imagery. The wife and infants and home were the sailor’s motivation to leave them: to defend and protect them. Thus he was in these three stanzas transformed from loving husband to the mighty foe of Britain’s enemies.

There is a similar poem/song by the same composer and poet called The Soldier’s Tear which follows this format. This fighting man leans upon his sword to wipe away a tear and takes his last look at a cottage in a valley, at whose door there is a ‘girl’. He is leaving his suitor rather than his family. In the final stanza the reader is asked ‘do not deem him weak/For dauntless was the Soldier’s heart,/Tho’ tears were on his cheek’. As these closing words hint, by the mid nineteenth century, tears were far less compatible with manliness and the stiff upper lip was arriving.ix My next task, therefore, is to move forward in time and establish when the sailor stopped shedding a tear.

i#Isaac Land, War, Nationalism, and the British Sailor, 1750-1850.

ii# Cited in Land, War, Nationalism, p. 89.

iii# I think this was in place earlier than might be indicated in Mary Conley, From Jack Tar to Union Jack: representing naval manhood in the British Empire, 1870–1918

iv# For a great overview of tears see Thomas Dixon: http://emotionsblog.history.qmul.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/History-in-British-Tears.pdf

v# Lady’s Magazine, 1782, pp. 343-344.

vi# AAA5177, National Maritime Museum.

vii# Birmingham University, John Shaw to Elizabeth Wilkinson (5 July 1811), CRL, Shaw/4.

viii#Sailor’s Tear, Bodley Ballads, Bodleian Library, Frame 19918. Also see sheet music, Victoria & Albert Collection, S.356-2012, c 19th century, and https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/20159

ix# Thomas Dixon, ‘The Tears of Mr Justice Willes’ – free copy at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13555502.2011.611696#.UpIlA8SpV8E

Really interesting, Joanne – and I couldn’t help thinking of Hector-Andromache-Astyanax and Odysseus-Penelope-Telemachus while reading (I think Odysseus even weeps while listening to a song), so the manly but tender soldier/sailor has a very distinguished history.

I enjoyed reading this post and it reminded me of when MacDuff weeps over his murdered wife and children in Macbeth. When exhorted to ‘bear’ it he retorts ‘I must feel it like a man’ – another, earlier, instance of manly tears.

Very interesting, Joanne. I have been working on a parallel thread which might interest you – namely how do men manage the tension between their need for emotional expression and cultural currents which proscribe this. Song offers some fascinating insights into this.

This is a really fascinating article Joanne. I’m interested in the degree to which the image of the manly weeping sailor was constructed specifically for a female audience. One class of documents that are surprisingly low on manly weeping are Napoleonic POW narratives. Despite the harrowing experiences many of these men endured, their reminiscences are noticeably low on tears. It seems to me that the predominant narrative style is stoicism touched with bleak humour. Of course few of these accounts were originally intended for publication so I wonder how much that influenced the stylistic and emotional motifs they employed?

Also, on an unrelated note, manly weeping also seems to be a transatlantic phenomena, I seem to recall that there are more than a few manly tears shed in Melville’s White-jacket e.g. “In our man-of-war world, life comes in at one gangway and Death goes overboard at the other. Under the man-of-war scourge, curses mix with tears ; and the sigh and the sob furnish the bass to the shrill octave of those who laugh to drown buried griefs of their own.” Sadly, I am woefully badly read in American literature so I don’t know how widespread this is.

Pingback: History Carnival #128 « khronikos: the blog

Excellent piece, Joanne. The tension between the domestic and the martial, the sensible/emotional and the stoical is ever-present for Georgian sailors, I think. Thomas Francis Fremantle writes of shedding tears to Betsey, as you know. What I’m left wondering is what sorts of tears sailors are allowed to shed, as I suspect that this is still highly gendered. Tears of relief after a battle (when thinking of what might have been re: his family), tears of sorrow (for the loss of loved ones) and tears of joy are all acceptable … are there any others? Do you ever find sailors weeping other sorts of tears, though (of pain, frustration, etc.)?