HMS M33 is one of only three surviving British First World War warships today, half way through the centenary of that conflict (although there is a very real chance that number might be reduced to two before long, if HMS President can’t secure funding for restoration and a permanent berth – see http://www.hmspresident.com/). Having lost its berth in London, HMS President cannot currently be visited, and given that HMS Caroline is now undergoing further restoration work, to return to public display in the Spring, if you want to visit a British WW1 warship right now, M33 is the only option.

I visited HMS M33 back in July, a few weeks before seeing HMS Caroline, and in fact there are many points of comparison with Caroline so if you haven’t yet seen my blog on that vessel, I’d encourage you to do so. Both ships fall under the umbrella of the National Museum of the Royal Navy, and a similar philosophy seems to have been adhered to with their restorations. Both vessels seem to have had a fairly ‘light-touch’ restoration, focussing on conservation and sympathy with the existing fabric. The effect has very much been to present M33 as a worked-in and lived-in vessel, complete with chipped paint and rust-stains.

Naturally, there are differences – the light cruiser Caroline is two and a half times the length of M33, and four times the displacement. While Caroline was a sea-going vessel intended to act with the dreadnought fleet, M33 had a very different purpose, effectively as a mobile, seaborne artillery battery to act with land forces. While Caroline fought in the climactic sea battle of Jutland, M33 took part in another famous and controversial action, the campaign at Gallipoli.

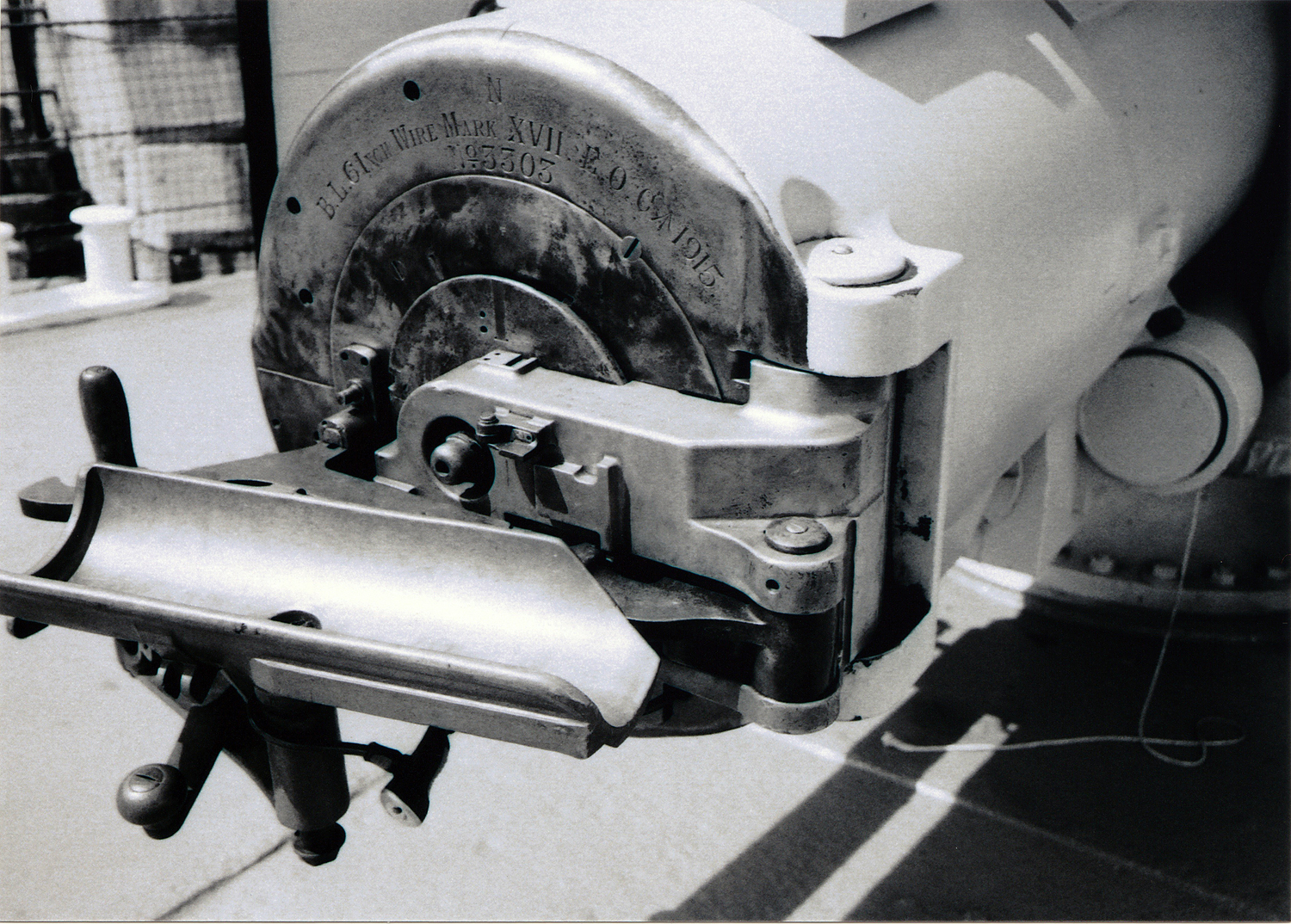

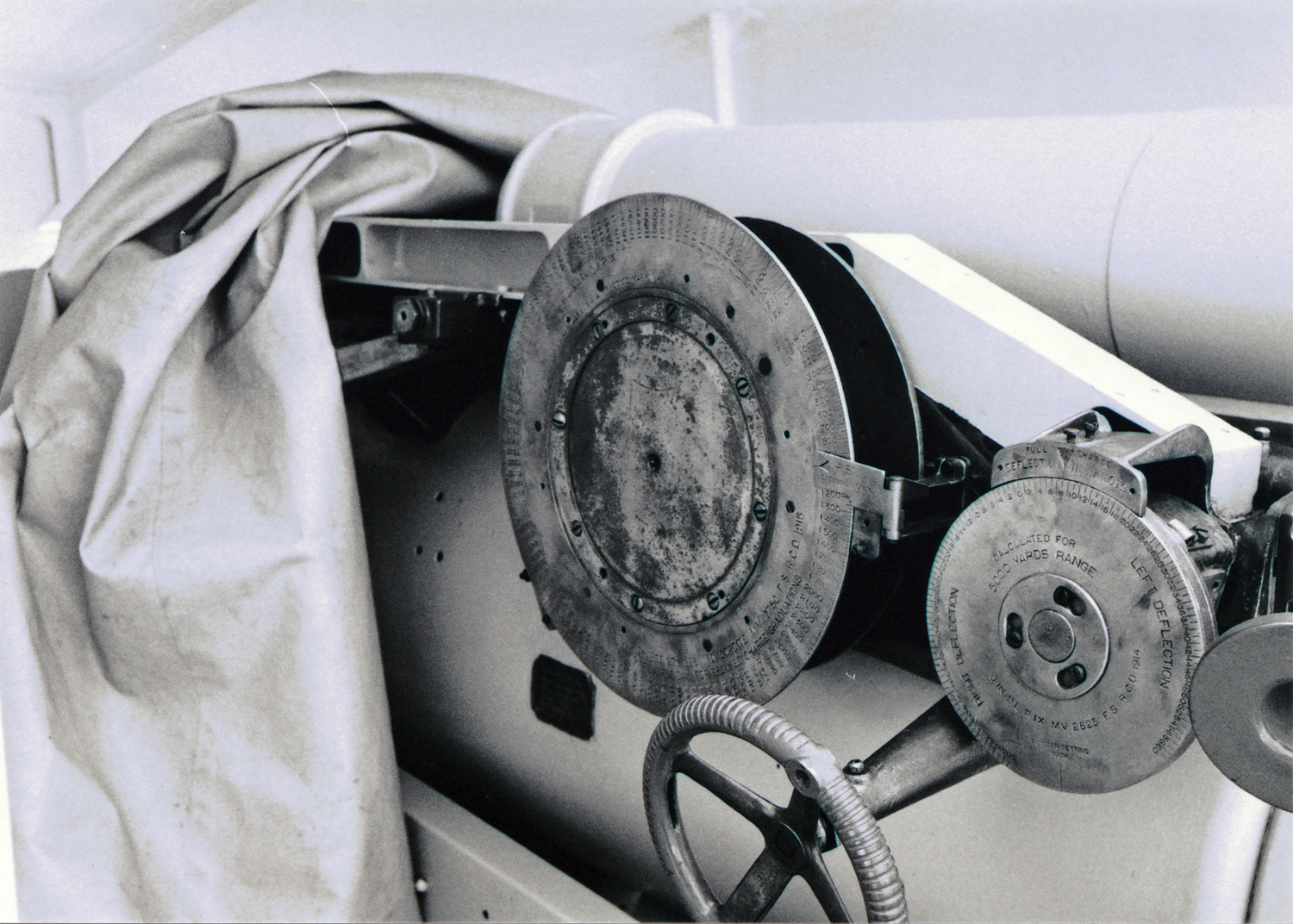

M33 was conceived shortly after the outbreak of WW1, after three river gunboats built for Brazil but pressed into RN service showed their value as shore bombardment vessels off the Belgian coast in late 1914. These craft, known collectively as monitors (after the US Civil War ironclad), were designed for shallow waters and proved highly useful for supporting amphibious operations. At the same time, they were much cheaper and, to put it bluntly, more dispensable than seagoing vessels. M33 was ordered in March 1915 as part of a series of craft to make use of a number of 6 in. guns that had just become available from the new super-dreadnought Queen Elizabeth-class, which mounted fewer than initially planned. Therefore, a new class of monitor was hurriedly designed by young Admiralty constructor Charles Lillicrap to make use of the supply of guns and mountings. M33 was to be built at Harland and Wolff, but the work was passed to the nearby Workman Clark shipyard.

One of the main differences between the two vessels as they exist today is that M33 is dry-docked, in the historic No.1 Dry Dock at Chatham, while Caroline is displayed afloat. This enables the visitor to M33 to inspect the exterior of the hull at close quarters, which the NMRN has exploited to the full. Rather than simply fitting steps from the top of the dry dock, the museum decided to make access to the vessel via the base of the dry dock, and a platform the length of the vessel gives a wonderful standpoint for inspecting both M33 and the 200-year-old structure it resides in. The hull has been painted in the striking black and white ‘dazzle’ camouflage it wore in the Russian Civil War in 1919.

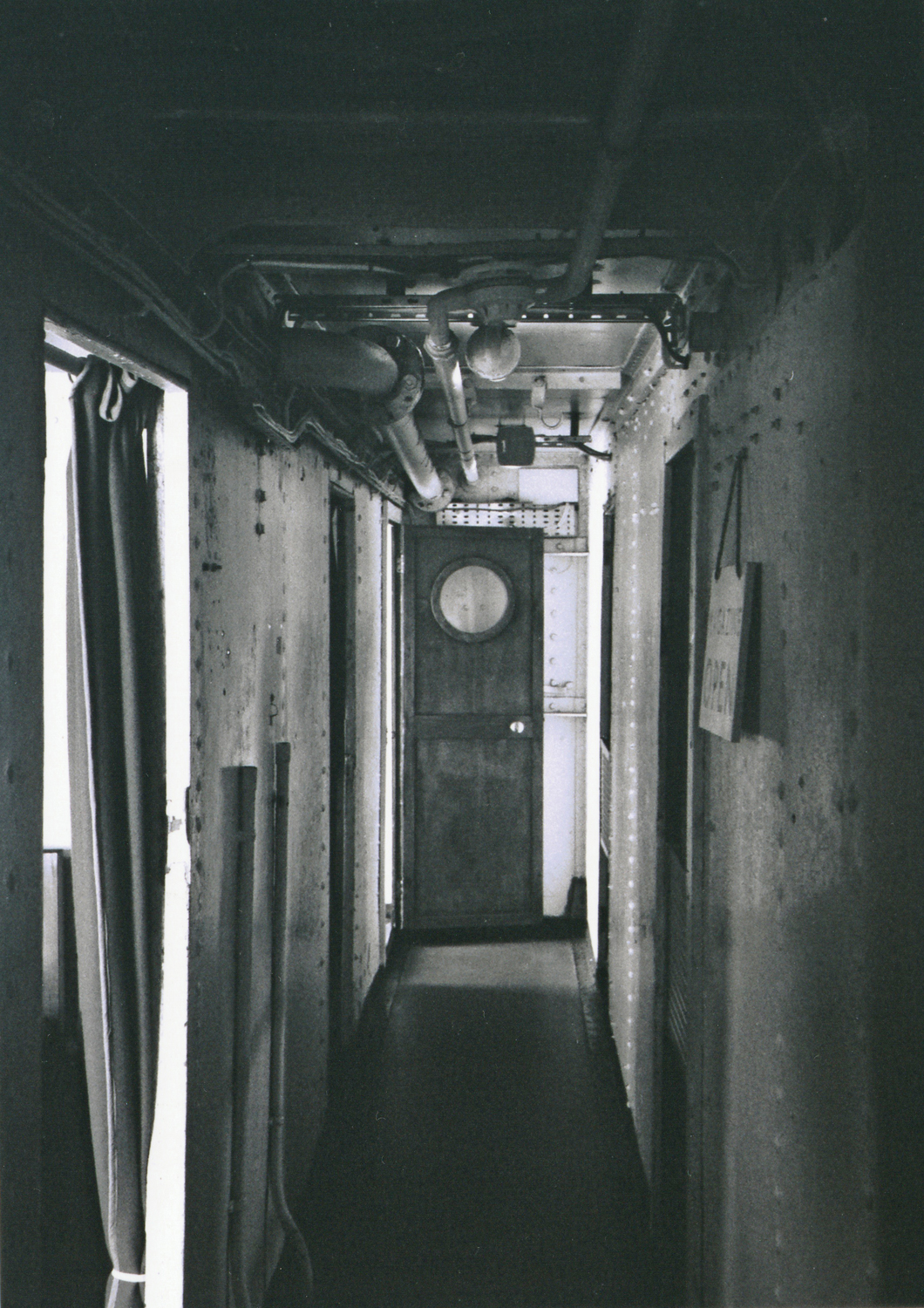

Entry to M33 itself is via a door through the hull which brings you out in the lower deck, with the ratings’ messdeck in the forecastle to your left, and which can be viewed via a platform. This space has been fitted out roughly as it would have been in 1915, and in truth is doesn’t take much more than a few hammocks and benches to get an impression of what it would have been like to live in, exposed frames and deck beams and all.

From there, the visitor moves aft into the engine room space. The machinery was removed in 1943, so the mid-section of the hull (extending into the upperworks) is largely empty, though one or two pieces of original equipment remain. The NMRN has taken the opportunity to utilise the space in the same way as HMS Caroline’s drill hall, to screen a film (in this case about the Gallipoli campaign) introducing the ship and putting it in context. It’s easy to see how this space could be used in future for more specific exhibitions and events in future. The empty areas of M33 also provide another feature that is less apparent in HMS Caroline – access to the structure of the vessel. As Caroline is not yet open to the public below the waterline, and as M33 is so much smaller, the engine and boiler rooms show the frames and beams to good effect, much as the original hull plating can be inspected at close quarters outside.

As with Caroline, visitors to M33 can see the Captain’s and officers’ cabin, wardroom, and after magazine, which have been restored to a semblance of wartime appearance. The main difference that’s apparent with Caroline is the size of these spaces. By contrast, the cruiser feels roomy and spacious. The Captain and officers of M33 existed in hutch-like cabins in the single-deck upperworks, separated from communal areas by curtains only. The Captain’s day ‘cabin’ is more or less filled by a single small desk, and partitioned from his tiny sleeping space. The galley contains barely space for one person in amongst the stove and utensils.

The wheelhouse is by contrast, surprisingly large for such a small vessel, light and airy, and fully enclosed, though there are platforms above which would have been used as an open bridge.

Another important difference between M33 and Caroline is that the former mounts genuine 6 inch 45-calibre Mk.XVII guns on Mk IX pedestal mounting with known histories. The detail and patina of the original guns makes a huge difference from the replicas mounted on the cruiser. These were the monitor’s raison d’être and it really adds to the experience that they are original.

Discreet displays give more information about the men who served on M33 in combat with extracts from diaries and personal belongings helping to bring the ship and its history further to life. Furthermore the volunteers are pleasingly enthusiastic and knowledgeable, happily relating information and anecdotes about the monitor’s history as they show the visitor around.

HMS M33 can be visited at the Portsmouth Naval Dockyard with a combined ticket or a single-attraction ticket from the National Museum of the Royal Navy. It is a must-visit for anyone interested in WW1 naval history. There is precious little ‘real steel’ left from this period, and it is an honour and a privilege to be able to see and touch a craft that was present during such momentous events.

It’s a superb vessel. I was privileged to take part in the filming for the on-board Gallipoli film (I ‘star’ in a few sequences – the Gallipoli landings of 25th April as an infantryman, one of the gunners on the M33’s 6 inch gun when it arrives in August then back to being an infantryman for the evacuation of Gallipoli, all filmed in the space of one day, partly on M33 in the morning and then a frantic drive to Lepe Beach to filming the landing/evacuation in the late afternoon/early evening!). My Great-Grandfather served at Gallipoli, in a Scottish Territorial Force mountain gun unit, so must surely have seen M33 in action, so now that I’m part of the exhibit on board M33 is something I’m very proud of indeed