HMS Nubian is not a famous name, but as Alex Clarke writes here, it should be…

|

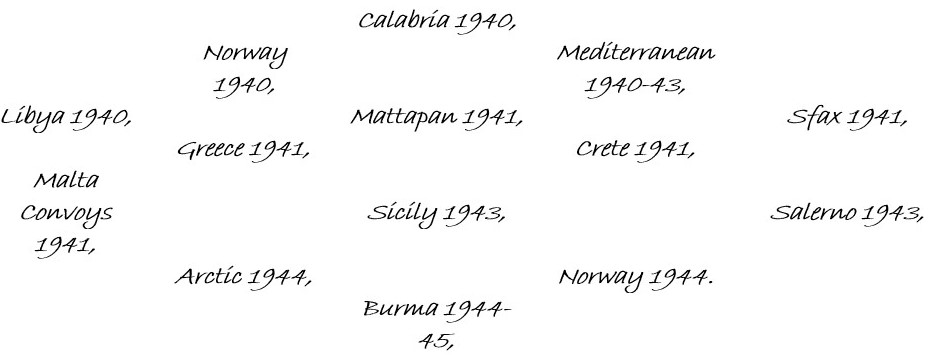

| Figure 1. The Battle Honours of HMS Nubian. Picture: Authors Own Creation. |

“The dominion of the sea, as it is an ancients and undoubted right of the crown of England, so it is the best security of the land… The wooden walls are the best walls of his kingdom”

These are the words of Thomas Coventry, Baron and Lord Keeper of the Great Seal in a speech to judges, 17th June 1635; three hundred and ten years later he could have replaced ‘wooden walls’ with HMS Nubian. After all her battle honours (above) run like a list of the Royal Navy’s WWII, this was a ship which could easily lay claim that title of Swiss army knife destroyer (although to be honest HMS Ashanti, HMS Eskimo and HMS Tartar could make a good run for it as well), HMS Nubian.[i] Only HMS Warspite would exceed her in WWII battle honours and with all this it’s no surprise that she has already been mentioned in this series in the articles about (in order published) HMS Afridi, HMS Ashanti, HMS Tartar and HMS Gurkha.[ii] Despite this, HMS Nubian is in many ways the quietest achiever of a class which, despite the press attention some of the members achieved and despite their involvement and sacrifice, were not flaunters.

This is typified by the report compiled by the RN of Nubian’s service after WWII, it describes that after taking part in the landings at Salerno and Sicily.[iii] She then “had a busy time helping to stop supplies from reaching Rommel, and sank at least two big merchant ships and one destroyer”. [iv] Whilst conducting what was considered the “probably the best work of her career” she regularly bombarded Pantelleria, Lampedusa, Catanai, Augusta and Salerno, expending thousands of rounds in support of allied troops – nearly 2,000 rounds into Salerno alone during a 10 day period in September 1943.[v] Even with all this written about her, all the reports on her service, when writing to enquiring cadet unit officer, Nubian was summed up by the head of the Historical section minimally[vi]:

“H.M.S. Nubian was a destroyer of the ‘Tribal’ Class, completed in 1938, which served with distinction throughout the Second World War. She was in the Mediterranean until after the end of the war with Italy in September, 1943, taking part in the Battle of Mattapan, the defence of Crete, the capture of Sicily, and other operations. Following a refit in the Tyne in the winter of the 1943-1944 she served in the Home Fleet for the rest of 1944, and in the Far East in 1945. She was placed on the disposal list in 1949.”

This itself, is not entirely accurate, as while Nubian started WWII, along with the rest of the 4th Destroyer Flotilla (DF) she belonged to then, in the Mediterranean – they didn’t stay there.[vii] With the war not starting as quickly there as expected, 4th DF was called back to Britain and were almost immediately employed in operations around Norway. However, the Mediterranean didn’t stay so quiet and soon Nubian and her sister Mohawk were transferred from 4th DF to 14th DF, in fact they were back in warmer waters by the 17th of May 1940[viii]. This meant that by March 1941 they were reliable fleet units that Admiral Cunningham felt comfortable using in critical roles.

Matapan is an interesting battle, mostly because it has a distinction of being one of the few battles which conformed to one side’s pre-war doctrines. The RN did manage to use an air attack to slow down the enemy, it did use cruisers to then track that enemy, whilst the battle fleet closed in and it did fight it at night. What is often forgotten about this battle though is that it was a convoy protection battle, at this time the RN were heavily involved in protecting convoys of filled with British Army personnel, equipment and supplies to Greece – it was too tempting a target for the Italian navy to ignore.[ix] However, as is often with chases the British forces started to spread out, needing to concentrate his cruisers on the enemy, Cunningham turned to his cruiser like destroyers, HMS Nubian & HMS Mohawk to fill the gap – “to form a visual signal link between Pridham-Wippell’s cruisers and the battlefleet”.[x] This of course served two purposes, it kept the need for ‘noiser’ radio communication to a minimum, but it also provided a means of preventing the Italians managing to slip unnoticed between the two groups of the British Force, either with the intention of escaping or surprising the main force.[xi]

Despite its billing as conforming to pre-war plans/exercises, the battle was not all the British hoped it would be, rather than the Battleship Vittorio Veneto (which had been damaged, but not crippled by an air strike from HMS Formidable’s swordfish) they had to make to do with three heavy cruisers, the already crippled by aircraft Pola, plus her sisters the Zara and Fiume which Admiral Iachino had despatched back to recover her.[xii] In the night action which took place, the destroyers role was find and fix the enemy with searchlights, so that the battleships could pummel with reduced risk of a torpedo being sited on to them.[xiii] It was a short sharp battle, the RN had prepared extensively for night fighting, from technology such as flashless charges for gun firing (again to minimise the exposure of their position, but also so as not to blind gunners), to the as important regular practicing of it.[xiv] With all this focusing on supporting the battleships, even with the melee action that had developed, the British Destroyers, even the Tribals didn’t get to be as prominent as they might have been in a larger action.

Still though, it was HMS Nubian which took the final action in the battle, firing a torpedo into the Pola that caused her to sink at 04:03hrs on the 29th of March, after the British destroyers had finished evacuating her crew.[xv] It was a battle which didn’t go quite as hoped, even though it went to plan – and despite the debate about a poorly worded signal from Cunningham, it never really could have, because to catch up with the main fleet would have left the British force very close to the Italian coast, it’s air force and fighting in daylight, i.e. victory could well have still resulted, but certainly not a practically lossless victory (the RN lost two swordfish & crews) that was achieved. Cunningham if given the opportunity, would probably have wished such an outcome for the next operation, where HMS Nubian would be damaged, it was an operation on scale of Dunkirk in both risk and necessity, but in its own way it would be far more fraught.

Crete was a direct result of Matapan, without the victory there, the troops and supplies to Greece would not have been able to be kept going at the same level; so when German and Italian forces invaded, the British would not have been as exposed. The first evacuation was from the mainland to Crete, in the scheme of things this went straightforwardly, however the forces as they arrived on Crete for whatever reason didn’t ‘gel’ and as such didn’t form a cohesive defence.[xvi] Therefore even though Cunningham set up a naval defence, which successfully prevented enemy forces coming by sea (with some help from the Luftwaffe and an Italian navy reluctant to commit heavy units), it was ultimately for nought as the enemy came by air and without the organisation in place, the ground forces were dislodged very quickly – requiring a further evacuation.[xvii] This evacuation was a far more difficult task, it was a task which would move Cunningham to make his most famous pronouncement “You can build a new ship in three years, but you can’t rebuild a reputation in under three hundred years”.[xviii] HMS Nubian, came very close to being the part of the three years rather than the three hundred.

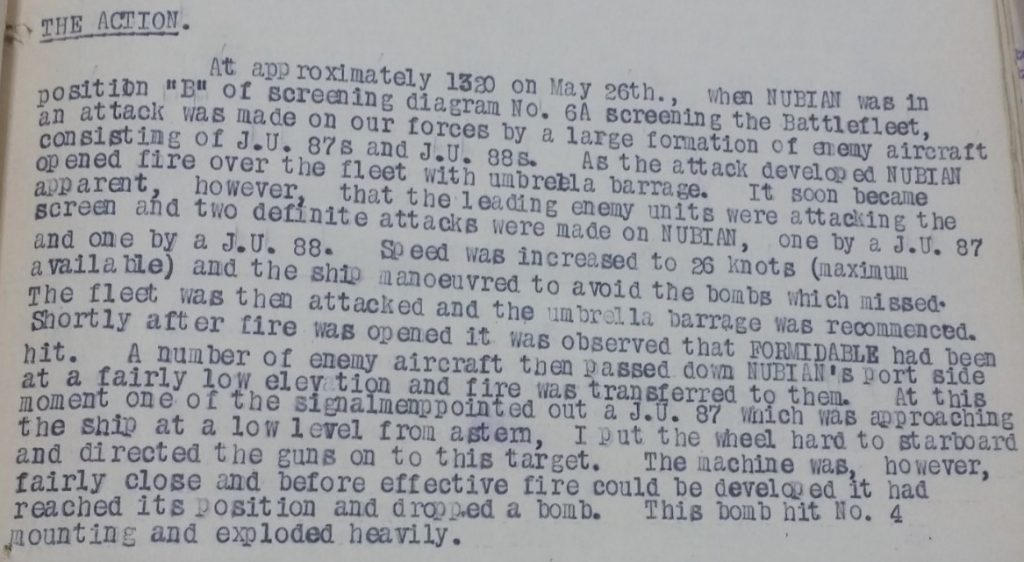

On the 26th of May, the destroyers of the 14th DF were escorting HMS Formidable and other main fleet units after a successful strike against Scarpanto airfield, the force was attacked by Ju87s and Ju88s. The Stuka’s went for Formidable, succeeding in hitting her twice.[xix] The waves kept coming Nubian was mainly focused on by the Ju88s, trying out what was then the new technique of skip bombing.[xx] However, the one bomb which did the most damage by taking out “Y” mounting, was dropped by a Ju87 though, the resulting explosion causing the loss of her stern as well as starting many fires (a sort of reverse Eskimo).[xxi] As with Eskimo though, Nubian was saved by excellent damage control and a miracle – despite losing her rudder, she had kept her propeller shafts and could manage 20 knots, steering by throttling the main engines, she was escorted back to Alexandria by her flotilla mate, HMS Jackal.[xxii] Her survival is made all the more amazing when it is considered that the RN lost 4 cruisers and 6 destroyers, as well as the damage received to HMS Formidable, 2 battleships, 4 more cruisers, another destroyer and a submarine; it was a sacrifice which almost erased the advantages won by Taranto and Matapan.[xxiii]

|

| Figure 2. An extract from HMS Nubian’s commanding officer, Cdr Ravenhill, after action report (TNA – ADM 199/810, 1941). Picture: Authors Own Collection. |

After such damage its unsurprising Nubian was out of action for a while, but she did return to service; but while in Bombay for repairs the RN took the opportunity to upgrade her, fitting radar, changing “X” mount to a twin 4in High-Angle AA system, along with some 20mm oerlikons and moving the depth charge throwers, to name just a few of the changes.[xxiv] This took time, but by October 1942, after 16 months, Nubian returned to the Mediterranean. [xxv] She served there till 1944, being a fixture of operations, evening capturing an entire island (and its garrison) by herself.[xxvi] Eventually though the war in the Mediterranean was done, Nubian returned the waters of Northern Europe, Artic Convoys and even Norway. Her war though, was not to end in those waters, in fact she earned further honour of the coast of Burma, conducting missions like Operation Irregular.[xxvii] Eventually though, even for ships like HMS Nubian, war does come to an end.

Post-war service lives for the Tribal class were cut short by the extent of their WWII service (even by September 1943, Nubian had travelled 53,556 nautical miles, underway for a total of 2,985 hrs, used 16,726 tons of fuel oil and had averaged 18.5knots – according to her then Captain, Cdr Holland-Martin) with its consequent wear on the ships and a change in vision.[xxviii] With lessons from WWII and reassurance of the numbers it had achieved by it, the RN was focused on achieving capability through commonality and maintaining a force of ‘specialists’ as best it could. Cruisers, destroyers, frigates all had roles, all had a purpose, a worn out class which straddled those duties was a complication. So the RN put to one side the experience of capacity and capability that the inter-war general purpose designs had provided it with.

The decision might have been different had surface raiders still been seen as a threat, but in the immediate post-WWII 1940s no surface raider threat existed. In fact it was only in 1949, the same year as the RN scrapped its Tribal class vessels, submarines ceased to be the only major sea threat, and surface battles reared their heads again, with construction commencing on the Soviet Navy’s Sverdlov class cruisers[xxix]. This might help to explain the survival of the Australian and Canadian vessels of the class, a decision which was substantiated by their excellent service in Korea[xxx]. Whatever the case it is certain that HMS Nubian, despite wanting to be useful to the very end, did not get the preservation or even the honourable end she deserved, instead she was used as target ship in Loch Striven in 1948, before being sent for scrap at Briton Ferry in June 1949.[xxxi]

References

[i] (TNA – ADM 199/810, 1941)

[ii] (Brice, 1971, p. 201) HMS Afridi, HMS Ashanti, HMS Tartar & HMS Gurkha

[iii] During which time HMS Nubian reached the milestone of steaming 300,000 miles since her first commission (TNA – ADM 199/810, 1941) – the distance from the Earth to the Moon and a little over a quarter of the way back.

[iv] (TNA – ADM 199/810, 1941)

[v] (TNA – ADM 199/810, 1941)

[vi] (TNA – ADM 199/810, 1941)

[viii] (TNA – ADM 187/7, 1940; TNA – ADM 187/8, 1940; TNA – ADM 187/9, 1940; TNA – ADM 199/810, 1941)

[ix] (Lambert, 2008, pp. 399-401)

[x] (Simmons, 2011, pp. 109-10) & HMS Sikh

[xi] This can be considered both a practical and expedient use of suitable ships, but also a legacy of Jutland, where the German High Seas Fleet had done such a manoeuvre to escape.

[xii] (Lambert, 2008, pp. 399-401; Simmons, 2011, pp. 129-34; Clarke, 2016)

[xiii] (Simmons, 2011, p. 129; TNA – ADM 186/72, 1925)

[xiv] So short and sharp that Cunningham compared it to murder and only one Italian vessel, the destroyer Alfieri was felt to have offered resistance (Simmons, 2011, pp. 130-1; TNA – ADM 116/3872, 1933-38; TNA – ADM 116/3873, 1937-39; TNA – ADM 186/145, 1929; TNA – ADM 186/158, 1937; TNA – ADM 203/90, 1929)

[xv] (Simmons, 2011, p. 133)

[xvi] This is the only way that it can be explained how a 15,000 strong force managed to defeat a 40,000 strong force…

[xvii] There were Italian landings on the 26th of May, but these were after the British fleet was concentrating on evacuation – they were also not even part of the original operational plan. (Simmons, 2011, pp. 155-60; Lambert, 2008, pp. 401-5; Brice, 1971, pp. 203-6; TNA – ADM 234/319, 1941; TNA – ADM 234/320, 1941)

[xviii] (Lambert, 2008, p. 404)

[xix] (www.armouredcarriers.com, 2017)

[xx] (Brice, 1971, p. 205; TNA – ADM 199/810, 1941)

[xxi] (Brice, 1971, p. 205; TNA – ADM 199/810, 1941), HMS Eskimo (I)

[xxii] (Brice, 1971, p. 205; TNA – ADM 199/810, 1941)

[xxiii] (Evans, 2010)

[xxiv] (Brice, 1971, p. 206)

[xxv] (Brice, 1971, p. 206)

[xxvi] (Brice, 1971, p. 210)

[xxviii] (Brice, 1971, p. 212)

[xxix] (Clarke, 2014)

[xxx] (Brice, 1971; Hastings, 2010; Malkasian, 2001)

[xxxi] (Brice, 1971, p. 213)

My great-uncle manned the pom-poms on the Nubian. He was in the Mediterranean and Japan. Would love to know more from there he went into the first SBS units..

My father Edward Mogey was a Pety Officer on this ship and my young life was filled with it,s exploits.

A fine ship with an exceptional record that should be remembered with pride.

My father joined the Royal Navy in 1931 and demobbed in 1946.

I was born on the 12th May 1945 and my birth was announced on the ships tannoy in Alexandria Harbour with the cry “another one for Churchill”

He is also remembered with pride

My Grandfather manned the Pom-Poms also on the Nubian, he kept a diary (which I have) from its commissioning in 38 till it’s repair In Bombay in 41. There is a mention in dispatches for something he did, found the entry, but as usual, no details.

I have a few photographs of the crew taken in the Mediterranean, it would be great to put some names to the faces.

My Grandfather was Arthur Henry Leonard.