Alexander Clarke’s second article examines the Royal Navy’s reaction to the emergence of the USSR’s Sverdlov Class gun cruisers.

“Although the Russian lack of aircraft carriers would make it hazardous for their Cruisers to operate outside the range of shore based fighter cover, the presumed long range of the Sverdlov Class makes it possible for them to operate as ocean raiders, particularly if the Russians have reason to believe that Allied carriers will not be met.”[i]

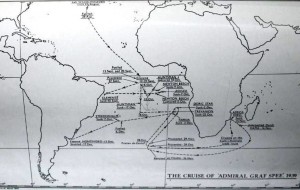

Surface raiders were a potentially deadly threat to a global trading nation such as Britain; whilst submarines were a problem, they were a containable problem – especially before the development of nuclear power. However, as had been demonstrated by the German cruiser Admiral Graf Spee of River Plate fame [ii] and others, surface raiders were for more unrestricted – hence killing them became such a priority. [iii] Therefore when the Soviets [iv] were seen to be constructing a similar capability a reaction was only a matter of time.

Figure 1.The Cruise of the Admiral Graf Spee, illustrating not only the number of its success but the range and breadth of them (Image from National Archives).[v]

The most commonly referenced British reaction to the emerging Soviet surface raider threat is the Buccaneer bomber, which were of course principally focused on not only low level nuclear strike of ground targets, but also the hunting down and destruction of surface raiders. [vi] The Royal Navy’s (RN) response though was not simply limited to this one thing, and in fact whilst carriers were focused on as the premier tool of global reach, it was realised there would never be enough available for the RN to achieve the global presence which would be required to protect the arteries of trade & supply from raiders/hunt those raiders down.[vii] Therefore just as it had during the 1920s and 1930s the RN turned to surface combatants.

While it is important to qualify this work with the understanding that the location and destruction of enemy surface raiders was not the sole, arguably perhaps not even a primary factor in the driving of warship design/development/procurement during this period it was a significant factor which should be considered as it can provide significant lessons for future design/development/procurement. This work will examine the relevant information in two sections: the first section will discuss what the Soviets Union did build, and just as importantly what the RN thought they were building. It is necessary to discern and differentiate both as it is in that the keys to understanding the RN’s and British Government’s operational perceptions as well as their opinion of their own strengths and weakness lie. The second section will move to the RN’s response; investigating what was planned, what was asked for and what was actually built. Wherever possible this work will apply context through the use of comparable allied construction. Finally this work will seek to bring all the threads of discussion together to answer the question that is its purpose; to what extent did the RN’s understanding of Soviet cruisers affected its ship procurement during the beginning phase of the Cold War.

To every action there is always…

The Sverdlov class were the second class of cruisers built by the Soviet Union following World War II (or the Great Patriotic War), they were the successors to the Chapayev class.[viii] However, the Chapayev class was designed during that conflict, and the Sverdlovs were the first class started after WWII. They were a significant part of plans which included Battleships and Aircraft Carriers – plans that were aimed at providing a brand new globe traversing Soviet Fleet.[ix] The Sverdlov’s range of 9000nm at 17kts which meant they were able to traverse vast tracts of ocean, and was not dissimilar to the Graf Spee’s 8,900nm at 20kts.[xi] They also compared well with those vessels put forward by other navies. [x] Due to the planned battleships and aircraft carriers not coming into existence (as a result of various internal political reasons as well as limitations of national industry [xii]) the Soviets had built a scaled/adapted version of the very effective (although ultimately defeated) WWII German navy.[xiii]

The USSR therefore found itself in possession of a force orientated around surface and sub-surface raiders, aimed at defending the USSR and its territory by in effect re-fighting the Battle of Atlantic/Arctic Convoys to prevent American resupply of their western European allies. An understandable strategic decision, as the Arctic convoy battles had left in many ways a greater memory in the minds of the Soviet leadership than the British: due to actual invasion, the USSR (like Malta) [xiv] had on occasions been just one or two ships away from defeat.[xv] Surface raiders were key to such as strategic notions as without their range and operational scope, submarines alone (especially in the pre-nuclear age) could not have achieved anywhere near the required results. However, the mirror was not an exact reflection of the German Navy, whilst Stalin might have insisted on the use of German technology and other modifications, the Sverdlov class were still very much Soviet in concept and design as can be seen by their lines (Figures 2 & 3).

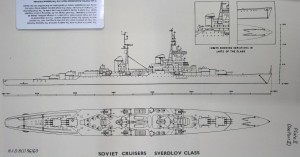

Figure 2: the Sverdlov class (image from National Archives [xvi]), this picture taken from an RN intelligence assessment highlights the clean lines and efficient looking hull bely the many problems which had had to be overcome by the rather undeveloped post-World War II(WWII) ship building industry in the USSR.[xvii]

Figure 3: the Sverdlov class (image from National Archives [xviii]), the fixation of the RN’s raiding worries for several years, this plan illustrates how heavily armed they were with twelve 152mm in four triple mountings, twelve 105mm in six double mountings all combined with a heavy Anti-Aircraft armament, torpedoes, sophisticated sensors, a top speed of 33kts and a range of 9000 nautical miles.[xix]

The Sverdlov’s range and displacement of more than 16,000tons compared positively with that of the pocket battleship/heavy cruiser Admiral Graf Spee.[xx] The 152mm or 6in guns (in RN speak) that provided their main batteries defined the Sverdlov Class as light Cruiser in origin rather than a pocket battleship, and were not dissimilar to those used by Ajax & Achilles at the Battle of the River plate. The choice of those guns instead of larger (nominally 8in guns) was an indicator of the intended purpose of the Sverdlov class.

The original order was for 40 vessels, and they were to be deployed with all the major Soviet fleets.[xxi] Sverdlov class ships first entered service with the Krasnoznamennyi Baltijskii Flot (KBF, Red Banner Baltic Fleet based at Kaliningrad) and Chernomorski Flot (CF, Black Sea Fleet based at Sevastopol). It was only as more of the class came into service that they were allocated to the Severnyi Flot (SF, Northern Fleet based at Severomorsk) and Tikhookeanski Flot (TOF, Pacific Fleet based at Vladivostok). After a transition period the KBF would contain three, the CF five, the SF just two, and the TOF received four.[xxii] All this though was to come; what the allies and the RN especially perceived, was the Soviet’s amassing a surface raider force at their all year ports with Atlantic/Indian Ocean access far beyond that which had been possessed by Nazi Germany.

This threat was felt so because the Sverdlovs’ main battery whilst not able to match those of larger ships (the legacy heavy cruisers and battleships still in service), were (especially in the pre-missile age) more than adequate when coupled with their heavy Anti-Aircraft (AA) armament to defend themselves against any likely opponents.[xxiii] This class of armament was certainly powerful enough to decimate any merchant vessels they found, as well as effective against shore targets of opportunity. More importantly their numbers and disposition meant that while in theory they could be blockaded in during any conflict, the likelihood was that some would already be at sea; like the Admiral Graf Spee had been. [xxiv] The consequence being they would be outside the blockade and would have to be hunted down while they ran amok amongst world’s sea lines of communication (SLOCs) – the very lines of communication that international trade and war supplies would use and therefore that Britain would be dependent upon.[xxv]

The RN, as is illustrated by its own documents, the Supplementary Naval Intelligence Papers relating to Soviet & European Navies – Soviet Cruisers[xxvi] and Particulars of Foreign War Vessels Volume 1 – Soviet & European Satellite Navies[xxvii], had a pretty accurate view of the Soviet designs. Although of course understanding changed with time, and some figures given in the former appreciation had changed by the time the latter was written. An example of this knowledge is that the RN knew that the 105mm secondary armament were three-dimensionally stabilised, allowing them to be used as AA weapons. The RN also knew that alongside the 105mm there were sixteen twin 37/60 Bofors type mountings for close range engagement: weaponry that was combined with an extensive radar fit, (using NATO ‘nicknames’) a Big Net, a Sea Gull and 1-2 Knife Rest(s) all for Air Search as well as a Slim Net, a High Sieve and a Hair Net for Air/Surface Search.[xxviii] This comprehensive sensor and weapons fit meant that the Sverdlov class was very capable of protecting themselves on solo raiding missions.[xxix] Although certainly they were the most probable wartime scenario, solo missions however were not the biggest fear for the RN. The biggest worry were Task Groups, two or more Cruisers, possibly with Destroyer escorts. Such formations were felt to be a direct threat to any allied naval task group without an aircraft carrier.[xxx] However, it was not just the Sverdlovs’ war time potential that presented a problem for the RN.

The Sverdlovs were impressive; they had a crew numbering more than a thousand officers and men and their overall capabilities were a statement of Soviet power and reach. Such a statement was important to demonstrating the success of the communist system in the global battle for hearts and minds, or influence (as it was termed then), that was the constant feature of the Cold War.[xxxi] With their size, elegant design, space and radius of operation they were perfect tools for carrying out naval diplomacy – something they were used for regularly, even making successive visits to Britain itself.[xxxii] This for a Britain in the process of decolonisation, of transitioning from Empire to Commonwealth, served to as a further catalyst for the fear that former colonies might be tempted to turn to communism and therefore to change from being allies to enemies or perhaps more importantly suppliers to deniers.[xxxiii]

…An equal and opposite reaction.

The Sverdlov entered service with the Voenno-Morskoj Flot SSSR (VMF -Military Maritime Fleet of the USSR) in 1952.[xxxiv] The RN had twenty-nine cruisers on its books: twelve cruisers in service, two for training, twelve in reserve and three under construction/stalled building.[xxxv] These cruisers were the products/legacies of experience gained through the two world wars, countless minor actions and of course all the ‘peace time’ operations that had been feature of the previous century, years when such vessels were reliable backbone of the RN’s abilities. In peace time they showed the flag around the world supporting diplomacy, trade and peace (or perhaps more accurately – stability). During war time they were the leading escorts and the principle trade protection assets; it was the vessels of this type that were charged with clearing the oceans of the enemy. It is unsurprising therefore that when the RN perceived a commerce raiding strategy being developed by the Soviets, it turned to cruisers.[xxxvi]

The RN went through different levels of planning as the years transitioned and more information became available as to the role and nature of the VMF’s cruiser build, as well as how the Soviet used them. In 1949 a paper entitled “Ships of the Future Navy” concluded that conventional cruisers and destroyers would be replaced by an all-purpose light cruiser.[xxxvii] The RN’s plan to the same grand scale as the Soviet plan for the VMF, envisaging the replacement of twenty-three cruisers and fifty-eight destroyer leaders with 50 of the new light Cruisers. At that point, the new cruisers were described as cruiser-destroyers and planned to be armed with 5in guns while displacing less than 5,000tons. The conceptual cruiser-destroyers would displace two-thirds less than a Sverdlov, putting them at an obvious disadvantage despite them being envisaged by some studies as a counter to threat posed by that class.[xxxviii] The cruiser-destroyer program was not the RN’s sole cruiser design programme, however.

The guided-weapons (or missile) cruiser, the project which was a leap ahead from the all-gun cruisers that the Sverdlovs represented was well underway.[xxxix] It would prove the downfall of the phenotype of the all-gun cruiser.[xl] It was another cruiser-destroyer program; but differed in that it would eventually see service as the backbone of 1960s/70s RN surface forces, the County Class destroyers.[xli] In 1954 however the proposal was a cruiser with a displacement 18,300tons full load, and fitted with the same twin 6in guns as then in service equipping the Minotaur class.[xlii] This vessel therefore would have exceeded the size/status of the Sverdlov class in a basic way; and completely outclass it in terms of air defence capability due to being fitted with a twin launcher for Sea Slug Surface-To-Air Missiles (to be fed from a forty-eight cell magazine). Unfortunately this design was also dropped for various reasons in 1957, the most obvious being the financial restrictions upon the RN.[xliii] It was decided to go with a cruiser-destroyer design, and in the coup de’ grace to further new cruisers classes the design team responsible for them were transferred to the nuclear submarine project – reducing the likelihood of new designs emerging to virtually zero.[xliv] However, the RN still had several cruisers in service during this period, and furthermore it was during this time that the three Minotoaur class light cruisers, whose construction had been suspended following WWII, were modified and completed as the Tiger Class.

In 1954, two years after the Sverdlov entered service and only a year after it had visited the UK for the Queen’s Coronation Review, work began again on the Tiger class vessels.[xlv] Their construction as Minotaur class ships had been suspended not only due to the spending freeze bought in at the end of WWII (because of which there had been very limited funds for anything), but also because of a desire to step back and digest the lessons of the war before charging into new construction.[xlvi] These ships were seen as way to accelerate the entry of those digested lessons into service when it was decided to complete their construction, without the cost of a new class if there were mistakes.[xlvii]

Many felt the most important lessons were to do with firepower; a new 6in gun had been developed and was fitted to the Tigers when they entered service – each gun/barrel had a rate of fire of 20 rounds a minute, so the Tigers with two double gun turrets could each provide 80 rounds a minute of fire support for amphibious operations, as had proved to be important in the Korean War.[xlviii] The guns would also be excellent for destruction of merchant shipping, another projected operational role.[xlix]. The three Tigers as originally built had no guided weapons, but they were still considered useful: the RN did not expect guided weapons to come into service that quickly and believed that even when they did guns would have a place still in the fleets armoury. [l] The gun was successful, and the possibility of upgrading legacy vessels such as HMS Belfast of the Town class vessels was considered.[li]

This was not to be though and neither were the Tiger class really, none completing more than nineteen years as a commissioned vessel.[lii] This was in stark comparison to the Town Class’ average service life of thirty years.[liii] These were especially short service periods given that two of the Tiger class vessels (Tiger and Blake, the third, Lion, wasn’t in good enough condition even for this) had very extensive midlife upgrades/conversions, gaining missiles and helicopters at expense of the aft 6in turret.[liv] Their demise was a symptom of the wider cuts to Defence and Naval Spending; but it was also a reflection that these ships were not really up to the task required of them. With a range of 8,000nm at 16kts and a top speed of only 31.5kts they were just not enough to take on the Soviet surface raiders. They had been operationally confined to Task Group Operations and instead of providing a limited substitute for the aircraft carriers, the Tigers had needed their protection. For task force operations, the Tiger Class’ weapons and sensor fit was good, and provide an adequate contribution.The Tiger Class was not up to the standard needed for that primary, or justifying, mission of cruisers; protecting the SLOCs from surface raiders.[lv] Without that justification the Tigers became a very hard ‘sell’ for the RN in face of Treasury questions.[lvi][lvii]

Conclusion

Given these limitations, to what extent did the Royal Navy’s understanding of Soviet cruisers affect its ship procurement during the beginning of the Cold War? If impact was measured only in paper work generated, research accomplished and debate instigated then the Sverdlov class did have more than an equal and opposite reaction from the RN. However, the metrics for measurement of impact must also include materiel generated, in this case the resulting ships. Materiel analysis is complex; the RN had cruisers in service and because of the suspended Minotaurs/Tiger class it had the option of hedging its bets instead of building new vessels in response – despite all the innovative and interesting options that were examined. This certainly explains why the most visible response in terms of material to the Soviet surface raider threat was the development of the Buccaneer strike aircraft; an asymmetric response that made the most of what was available, rather than a more direct viable solution to the threat of Soviet surface raiders that the Sverdlov class represented.

Unfortunately for the RN, the transitional period of the 1950s limited the available options not only in terms of technology, but also in terms of what the fleet would be. One aspect of the transition from Empire to Commonwealth was the loss of the highly visible role/budget justification of imperial policing. In comparison to this contraction, technology was driving an across-the board classification-blurring increase in the size of warship designs as they were sought to accommodate the addition increasingly sophisticated equipment/weaponry; an example of this blurring being the cruiser-destroyer concept. In a time when there were many other draws on the public purse, such as the National Health Service, Nuclear Weapons and rebuilding a nation devastated by WWII, the growth of individual warships resulted in higher costs for the vessels themselves, for new systems and technology and for training.

In the end, the RN’s response was mostly (as far as surface ships were concerned) a vicious paper tiger. Adequate or even great designs on paper translated into warships completed during the period that were not up to the tasks they were envisioned to do. The importance of the response was such that successive Admiralty Boards put extensive effort into design programs, focused so many resources and fought so many Whitehall battles for vessels. Not entirely fruitless, these negotiations did lay the ground work for many other concepts to become reality, vessels which were up to missions required of them and which would be of considerable value in future conflicts. In addition to these benefits, the eventual selection of the 4.5in gun as the standard deck gun for all escorts after flirtations with 6in, 5in & 3in, and the decision to purchase Exocet SSM were consequence of the debates that affected not just the RN’s cruisers, but the whole fleet. Furthermore it must be remembered that throughout this period, the RN was never less than the second navy of NATO, and it kept to its own style – partly due to spending limits, but also perception of mission.[lviii] Whilst the USN went for the ‘Super Power Fleet’ as enshrined by experience of war in the pacific, the RN built something different, similar in image and scale definitely but always different – meaning the Soviets always had to consider the British when building their own ships.

This conceptual relationship between the Royal Navy and Soviet Navy was perhaps best illustrated by the fact both the Soviet Navy and the RN built Aviation Cruisers – or rather that is what they chose to describe their carriers for differing reasons.[lix] Furthermore, this piece of history does perhaps serve to shed some light on today’s events, and the current Russian naval rearmament.[lx] The procurement of Mistral class LHDs from France [lxi] along with the construction of new classes of warship in Russian Yards, is not a Mahanian challenge for dominance of the sea [lxii] but a quest for projection of influence and power which would serve to dispute that dominance.[lxiii] In simple terms the Russians like their Soviet predecessors in the 1950s are not seeking to match anyone in strength, but to match them in capabilities so as to be able to influence events in their favour. The question remains though whether their current naval rearmament will be as influential on the RN’s future construction today as it did in the 1950s, when it not only mobilised cruisers from slipways, but more importantly mobilised minds in search of countermeasures, producing systems, practices and decisions which effect the RN to this day.

Bibliography

Books

Brown, David K, and George Moore. 2012. Rebuilding the Royal Navy – Warship Design since 1945. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing.

Brown, Eric. 2007. Wings on My Sleeve. London: Phoenix.

Cable, James. 1983. Britain’s Naval Future. London: Macmillan Press.

Clarke, George Sydenham. 2007. Russia’s Sea-Power Past and Present, or the Rise of the Russian Navy. London: Elibron Classics.

Corbett, Julian S. 1911. Some Principles of Maritime Strategy. Uckfield: The Naval & Military Press Ltd.

Corbett, Julian S. 2005.b. England in the Seven Years War. Vol. II. II vols. London: Elibron CLassics.

—. 2005.a. England in the Seven Years War. Vol. I. II vols. London: Elibron Classics.

Corbett, Julian S., and H. J. Edwards, . 1914. The Cambridge Naval and Military Series. London: Cambridge University Press.

Duncan , Andrew. 2004. “Technology, Doctrine and Debate: The Evolution of British Army Doctrine between the World Wars.” Canadian Army Journal 7.1: 23-34.

Friedman, Norman. 1988. British Carrier Aviation. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

—. 2010. British Cruisers; Two World Wars and After. London: Seaforth Publishing.

Grove, Eric. 2005. “The Royal Navy and the Guided Missile.” In The Royal Navy, 1930 – 2000; Innovation and Defence, edited by Richard Harding, 193-212. London: Frank Cass.

Harding, Richard, ed. 2005. The Royal Navy, 1930 – 2000, Innovation and Defence. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis.

Hastings, Max. 2010. The Korean War. London: Pan Books.

Hill, J. R. 1988. Air Defence at Sea. Shepperton: Ian Allan Ltd.

—. 2002. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Royal Navy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hill-Norton, Peter, and John Decker. 1982. Sea Power. London: Faber and Faber Ltd.

Jane’s. 2001. Fighting Ships of World War II. London: Random House Group.

Kemp, Paul. 1993. Convoy! – Drama in Artic Waters. London: Cassell Military Paperpacks.

Mahan, A.T. 1987. The Influence of Sea Power Upon History 1660-1783. 5th Edition. New York: Dover Publications Inc.

Marriott, Leo. 2008. Jets at Sea; Naval Aviation in Transition 1945-1955. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Aviation.

Menon, Raja. 1998. Maritime Strategy and Continental Wars. Abingdon: Frank Cass Publishers.

Mitchell, B. R. 2011. British Historical Statistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O’Brien, Phillips Payson, ed. 2001. Technology and Naval Combat in the Twentieth Century and Beyond. London: Frank Cass Publishers.

Parker, Geoffrey, ed. 2005. The Cambridge History of Warfare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pearson, Michael. 2004. The Ohio & Malta, The Legendary Tanker that Refused to Die. London: Leo Cooper.

Richmond, Herbert W. 1934. National Policy and Naval Strength. London, New York, Toronto: Longmans, Green and Co.

Richmond, Herbert W. 1914. “Naval Officers Point of View.” In The Cambridge; Naval and Military Series, edited by Julian S. Corbette and H. S. Edwards, 39-54. London: Cambridge University Press.

Rohwer, Jürgen , and Mikhail S Monakov. 2006. Stalin’s Ocean-Going Fleet. London: Digital Printing (originally Frank Cass Publishers, 2001).

Smith, Peter C. 2002. Pedestal, The Convoy that saved Malta. Manchester: William Kimber, Crecy Publishing Limited.

Thetford, Owen. 1978. British Naval Aircraft since 1912. London: Putnam.

Wettern, Desmond. 1982. The Decline of British Seapower. London: Jane’s.

White, Rowland. 2009. Phoenix Squadron: HMS Ark Royal, Britain’s last top guns and the untold story of their most dramatic mission. London: Bantam Press.Unpublished Archival Sources

Unpublished National Archives, Kew

TNA – Admiralty: 1/20372. 1947. “ANTI-SUBMARINE MEASURES AND DEVICES (11-1A): Anti-submarine warfare: amendments to Confidential Admiralty Fleet Order.” ADM: 1/20372. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Admiralty: 1/20933. 1947. “ANTI-SUBMARINE MEASURES AND DEVICES (11-1A): Tactical use of helicopters in anti-submarine warfare.” ADM: 1/20933. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Admiralty: 1/20960. 1939. “ANTI-SUBMARINE MEASURES (11-1A): Development of anti-submarine warfare: training and investigation policy: reports etc.” ADM: 1/20960. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Admiralty: 1/21876. 1950. “ANTI-SUBMARINE MEASURES (11-1A): Anti-submarine warfare: nomenclature of maritime forces employed.” ADM: 1/21876. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Admiralty: 1/23041. 1948-51. “BOATS (11): Ship Design Policy Committee: proposals for the construction of Cruisers, Cruiser/Destroyers, convoy escorts and fast patrol boats.” ADM: 1/23041. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew).

TNA – Admiralty: 1/24433. 1953. “Development of submarine simulator for fleet anti-submarine warfare exercises.” ADM: 1/24433. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Admiralty: 1/25609. 1954. “The Introduction of Shipbourne Guided Weapons with the Navy.” ADM: 1/25609. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew), April 14.

TNA – Admiralty: 1/27600. 1953. “Visit of Soviet Cruiser Sverdlov to Spithead for Naval Review.” ADM: 1/27600. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Admiralty: 116/4109. 1940. “Battle of the River Plate: reports from Admiral Commanding and from HM Ships Ajax, Achilles and Exeter.” ADM:116/4109. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew).

TNA – Admiralty: 116/4320. 1941. “Battle of the River Plate: British views on German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee in Montevideo harbour; visits to South America by HMS Ajax and HMS Achilles.” ADM: 116/4320. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew).

TNA – Admiralty: 116/4470. 1940. “Battle of the River Plate: messages and Foreign Office telegrams.” ADM: 116/4470. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew).

TNA – Admiralty: 116/5632. 1948-52. “Ship Design Policy Committee.” ADM: 116/5632. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew).

TNA – Admiralty: 199/1730. 1945. “Director of Anti-Submarine Warfare: trade protection and Italian submarines.” ADM: 199/1730. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Admiralty: 199/1732. 1945. “Director of Anti-Submarine Warfare: training, submarine training ships, anti-submarine attack trainers.” ADM: 199/1732. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Admiralty: 203/84. 1924. “Admiral Richmond’s report on the Combined Exercise conducted at Salsette Island (Bombay) Combined Exercise.” ADM: 203/84. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew), December.

TNA – Admiralty: 223/714. 1959. “Translation of the 1949 Russian Book “Some Resullts of the Cruiser Operations of the German Fleet” by L. M. Eremeev – translated and distributed by RN Intelligence.” ADM: 223/714. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew), September 02.

TNA – Admiralty: 226/71. 1951. “Fast battery intermediate `B’ (S.S.0.1) design submarine: preliminary EHP figures, submerged trim.” ADM: 226/71. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew), July 23.

TNA – Admiralty: 239/533. 1960. “Supplementary Naval Intelligence Papers relation to Soviet & European Satellite Navies: Soviet Cruisers.” ADM: 239/533. London: United Kingdom, National Archives (Kew), November.

TNA – Admiralty: 239/821. 1959. “Particulars of Foreign War Vessels Volume 1: Soviet & European Satelite Navies.” ADM: 239/821. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew), January.

TNA – Admiralty: 259/248. 1957. “Self protection asdics for fast surface units.” ADM: 259/248. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Admiralty: 259/260. 1958. “Sweeping techniques against fast submarines in North Atlantic.” ADM: 259/260. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Admiralty: 259/338. 1957. “Manoeuvres of fast battery-driven submarines against trade convoys: part 1.” ADM: 259/338. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Admiralty: 259/339. 1957. “Manoeuvres of fast battery-driven submarines against trade convoys: part 2.” ADM: 259/339. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Admiralty: 302/11. 1960. “Comparison of effectiveness of Asdic types 184 and 195 against fast battery submarines.” ADM: 302/11. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Air Ministry: 65/175. 1945. “”High Tea” range tests with fast submarine Report No: 45/16.” AIR: 65/175. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew), May 25.

TNA – Air Ministry: 65/379. 1953. “Trial of the British directional sonobuoy Mk 1 series 2: Pt 2C maximum ranges of acoustic detection of a fast submarine by the British directional radio sonobuoy (trial No 300).” AIR: 65/379. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Amiralty: 1/30086. 1955-6. “Cruisers and Carrier availability.” ADM: 1/30086. London: United Kingdom National Archive(Kew).

TNA – Cabinet Office: 106/332. 1947. “Despatch on the sinking of the German Battle Cruiser “Scharnhorst” 1943 Dec.26, by Admiral Sir Bruce A. Fraser, Commander-in-Chief, Home Fleet (Supplement to London Gazette 38038) (H.M. Stationery Office 1947).” CAB:106/332. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew).

TNA – Cabinet Office: 106/335. 1948. “Despatch on the attack on the German battle Cruiser “Tirpitz” by midget submarines, 1943 Sept.22, by Rear Admiral C. B. Barry, Admiral (Submarines) (Supplement to London Gazette 38204) (H.M.Stationery Office 1948).” CAB: 106/335. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew).

TNA – Foreign Office: 371/100871. 1951. “Proposal to photograph new type Soviet Cruisers in the North Sea. Code NS file 1213.” FO: 371/100871. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Foreign Office: 371/106559. 1953. “Soviet ships off the Shetlands; visit of Soviet Cruiser Sverdlov to Spithead for the Coronation. Code NS file 1211.” FO: 371/106559. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Foreign Office: 371/122817. 1956. “Port of arrival for Cruiser: Sir W Hayter’s discussion with Mr Kuznetsov.” FO: 371/122817. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

—. 1956. “Soviet proposal that Cruiser carrying leaders should travel up the Thames.” FO: 371/122817. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Foreign Office: 371/122820. 1956. “Enquiry from Sir W Hayter as to whether UK naval attaché, Moscow, will travel on Cruiser.” FO: 371/122820. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Foreign Office: 371/122821. 1956. “Arrival and departure times and dates for Soviet Cruiser.” FO: 371/122821. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Foreign Office: 371/122830. 1956. “Leaders’ farewell message to UK prime minister from Soviet Cruiser.” FO: 371/122830. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Ministry of Defence: 15/282. 1948. “Attack of Cruisers by underwater projectiles.” DEFE: 15/282. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Ministry of Defence: 4/110/74. 1958. “Minutes of Meeting Number 74 of 1958.” DEFE: 4/110/74. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew), August 19.

TNA – Ministry of Defence: 4/111/76. 1958. “Minutes of Meeting Number 76 of 1958.” DEFE: 4/111/76. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew), August 26.

TNA – Ministry of Defence: 5/84/146. 1958. “Memorandum Number 146 of 1958. Chief of Staff requirements for Cruisers East of Suez: note by Vice Chief of Naval Staff. .” DEFE: 5/84/146. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew), June 2.

TNA – Ministry of Defence: 6/51/104. 1958. “Requirement for Cruisers East of Suez. .” DEFE: 6/51/104. London: United Kingdom National Archvies (Kew), August 21.

TNA – Prime Ministers Office: 11/1014. 1955. “Reconnaissance of Soviet Cruisers by HMS Wave and RAF aircraft.” PREM: 11/1014. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA – Prime Ministers Office: 2/413/7. 1945. “Final statement on anti-submarine warfare.” PREM: 3/413/7. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew), June.Websites

Clarke, Alexander. 2013. “Peaking Obsolescence or Forgotten Innovation?” British Naval History. December 09. Accessed February 21, 2014. http://globalmaritimehistory.com/peaking-obsolesence-forgotten-innovation/.

Defence Industry Daily. 2014. “Russia Orders French Mistral Amphibious Assault Ships.” Defence Industry Daily . February 12. Accessed February 22, 2014. http://www.defenseindustrydaily.com/russia-to-order-french-mistral-lhds-05749/.

Kislyakov, Andrei. 2007. “Will Russia create the world’s second largest surface navy?” RIANOVOSTI. November 13. Accessed February 22, 2014. http://en.ria.ru/analysis/20071113/87843710.html.

Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives. 2010. Survey of the Papers of Senior UK Defence Personnel, 1900-1975 : Richmond, Sir Herbert William (1871-1946), Admiral. Kings College London. Accessed November 24, 2010. http://www.kcl.ac.uk/lhcma/locreg/RICHMOND.shtml.

Scott, James Brown. 2008. Source taken from a Series of Lectures given in 1908: Peace Conference at the Hague 1899; Report of Captain Mahan to the United States Commission to the International Conference at the Hague, Regarding the Work of the Second Committee of the Conference. Accessed March 4, 2012. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/hag99-07.asp.Endnotes

I (TNA – Admiralty: 239/533 1960) – General Remarks

II (TNA – Admiralty: 116/4109 1940, TNA – Admiralty: 116/4320 1941, TNA – Admiralty:

116/4470 1940) – the Soviets were also very interested in the various German Navy

Cruiser actions, especially the voyage & demise of the Admiral Graf Spee (TNA –

Admiralty: 223/714 1959)

III (TNA – Cabinet Office: 106/332 1947, TNA – Cabinet Office: 106/335 1948)

IV Please note when talking about the Cold War period Soviet will be used instead

Russia as the denominator, however when discussing post-Cold War period Russia will

be used as it.

V (TNA – Admiralty: 116/4109 1940)

VI (White 2009, 35, Thetford 1978, 66-7)

VII (TNA – Ministry of Defence: 5/84/146 1958, TNA – Ministry of Defence: 6/51/104

1958, TNA – Admiralty: 1/30086 1955-6, TNA – Admiralty: 116/5632 1948-52)

VIII (TNA – Admiralty: 239/821 1959)

IX (Rohwer and Monakov 2006, 199) – It is interesting to note that the RN’s documents

underestimate the endurance (estimating 8,700nm at 18kts (TNA – Admiralty: 239/821

1959)) although still respectful.

X The RN’s Minotaur class could do 6,000nm at 20kts (Friedman, British Cruisers; Two

World Wars and After 2010, 407) and the USN’s Worcester class which could do

9,000nm at 15kts

XI (Jane’s 2001) – the fact that it’s not dissimilar should be no surprise considering

Stalin’s fixation on using both captured and some pre-WWII procured German

technology as a starting point (Rohwer and Monakov 2006, 198)

XII (TNA – Admiralty: 1/23041 1948-51, TNA – Admiralty: 116/5632 1948-52)

XIII Something the Soviets had done extensive study on, and which the RN was

interested in – for example they obtained a translation of the book Some Results of

the Cruiser Operations of the German Fleet by L.M.Eremeev (TNA – Admiralty: 223/714

1959)

XIV (Pearson 2004, Smith 2002)XV (Kemp 1993)

XVI (TNA – Admiralty: 239/533 1960)

XVII (Rohwer and Monakov 2006, 197-9)

XVIII (TNA – Admiralty: 239/533 1960)

XIX (Rohwer and Monakov 2006, 199, TNA – Admiralty: 239/533 1960)

XX (Rohwer and Monakov 2006, 199)

XXI Although only 25 were ordered and 14 eventually built – some in a modified form

(Rohwer and Monakov 2006, 276-7)

XXII (Rohwer and Monakov 2006, 276, TNA – Admiralty: 239/533 1960)

XXIII They could chuck a 115lb shell, 34,000yrds at a speed of 2,850ft/s (TNA –

Admiralty: 239/821 1959) or in metric, a 52.16kg shell, 31.09km at a speed of

868.68m/s (or Mach 2.55)

XXIV (TNA – Admiralty: 116/4109 1940, TNA – Admiralty: 223/714 1959)

XXV (TNA – Admiralty: 116/5632 1948-52)

XXVI (TNA – Admiralty: 239/533 1960)

XXVII (TNA – Admiralty: 239/821 1959)

XXVIII (TNA – Admiralty: 239/533 1960, TNA – Admiralty: 239/821 1959)

XXIX Hence the need to develop a new aircraft to replace those already in the process

of being procured or in service – many of the latter

XXX (TNA – Admiralty: 239/533 1960)

XXXI (TNA – Ministry of Defence: 5/84/146 1958)

XXXII (TNA – Foreign Office: 371/106559 1953, TNA – Foreign Office: 371/122817 1956,

TNA – Foreign Office: 371/122821 1956, TNA – Prime Ministers Office: 11/1014 1955)XXXIII Admiral Ralph Edwards could have been argued to have been rather perceptive

when writing in the 1949 Ships of the Future Navy (TNA – Admiralty: 116/5632 1948-

52) that “Overseas police duties, calls for which, in a ‘Cold War’ type of peace, may be

expected to increase rather than diminish”.

XXXIV (Rohwer and Monakov 2006, 277)

XXXV (Wettern 1982, 396)

XXXVI (TNA – Admiralty: 116/5632 1948-52) – here they actually state, on the topic of

protection of seaborne trade, “This could be done by aircraft carriers, but more

extravagantly and less certainly”

XXXVII (Brown and Moore 2012, 29, TNA – Admiralty: 116/5632 1948-52) – An aim

arguably achieved only recently with the recent entry into service of the 8,500ton

Daring class Destroyers; at least in terms of displacement.

XXXVIII Design Study II (Brown and Moore 2012, 33, TNA – Admiralty: 116/5632 1948-

52)

XXXIX (TNA – Admiralty: 1/23041 1948-51, TNA – Admiralty: 116/5632 1948-52, TNA –

Admiralty: 1/25609 1954, TNA – Admiralty: 1/23041 1948-51)

XL (Brown and Moore 2012, 32-3, TNA – Admiralty: 1/25609 1954)

XLI (Brown and Moore 2012, 35)

XLII (Brown and Moore 2012, 32)

XLIII (Mitchell 2011, 594) even though the budget actually increased slightly in real

terms when inflation is factored in, the cost of procurement of new systems &

repairing/upgrading/maintaining the war worked ships meant that expenses rose

faster.

XLIV (Brown and Moore 2012, 35)

XLV (TNA – Admiralty: 1/27600 1953)

XLVI This included aircraft, which at the end of World War II were arguably in a worse

state (A. Clarke 2013)

XLVII As shown by the emphasis placed on the Cumberland trials (TNA – Admiralty:

1/23041 1948-51)XLVIII (Hastings 2010, Hill, The Oxford Illustrated History of the Royal Navy 2002)

XLIX In simple terms each vessel could with their 6in guns alone deliver 5tons of

ordinance a minute at a range of up to 13 miles (Wettern 1982, 100)

L (TNA – Admiralty: 1/23041 1948-51, TNA – Admiralty: 1/25609 1954) – although it was

openly acknowledged that they were to be the last All-Gun ship (Wettern 1982, 100)

LI (Wettern 1982, 93-5, TNA – Admiralty: 1/23041 1948-51)

LII (Wettern 1982, 392-439)

LIII (Friedman, British Cruisers; Two World Wars and After 2010)

LIV (Friedman, British Cruisers; Two World Wars and After 2010, 319-21)

LV (TNA – Admiralty: 116/5632 1948-52)

LVI (TNA – Admiralty: 239/821 1959)

LVII If a service cannot even justify a weapon system to itself, the how is it supposed to

justify it to Ministers, let alone an organisation of the Treasury’s accountancy calibre?

LVIII (Grove 2005)

LIX (Brown and Moore 2012, 62-71, Friedman, British Cruisers; Two World Wars and

After 2010, 321-3) – Although to be technical the Invincible class were described as

‘Through Deck Cruisers’.

LX (Kislyakov 2007)

LXI (Defence Industry Daily 2014)

LXII (Mahan 1987)

LXIII In fact it seems to perhaps be a more Corbettian approach to naval strategy (J. S.

Corbett 1911)

Which Royal Navy Ships made the official visit to Russia c.1950/

The Sverdlov class cruisers were primarily intended by Stalin to operate in a defensive role off the Russian coast and in the Black Sea were they would have been covered by a powerful Soviet airforce and submarines and the often ignored upgraded shore mounted 12 inch twin batteries which had a range of 40 km, and a rate of fire as high as any battleship. The cruisers were also intended for a political presence and pressure role in third world areas of interest to the Soviet Union. The Ordzhonikidze was transferred to Indonesia in July 1962 and had it had Soviet technicians and crew aboard as might have eventuated but for the embarrassment of the Soviet failure in the Cuban missile crisis, the Sverdlov might have put pressure on the Royal Navy fleet during the confrontation. Admiral Gorshkov was planning to operate a couple of the Sverdlovs predecessors the Chapeyev cruisers from a new Russian naval base in Cuba and was very frustrated that with only 12 Sverdlov cruisers in the Soviet fleet in 1962, none could be spared to probe the USN defense during the crisis in company with the 4 foxtrots subs and the preliminary operations were November SSNs in 1961-62 had run under USN carrier task forces at 30 knots, suggesting a degree in invulnerablity to conventional defence. Gorshkov certainly saw cruisers operations as possible in 1962 before the presence of Oceanic surveillance satellites and with the overconfident USN not conduction much aerial ocean surveillance with its Neptune maritime patrol planes. Even today an aggressor’s first target would be to knock out ocean surveillance satellites of the other side.

The ability of the Royal Navy legacy and later Tiger cruisers to check any independent Sverdlov operations or counter them off the Russian coast, Norway or in the Mediterranean or Black Sea remains doubtful. The RN regarded its three remaining County class 8 inch cruisers as is most effective units in the late 1940s but after 20 years use they were worn out by 1950, but the the geared turbines and boilers in the incomplete Tigers and 4th Tiger HMS Hawke could have been used to reengine the County class cruisers. Having worn out the County class cruisers, the largest and potentially most suitable legacy cruisers for modernisation and deep water operation against the Sverdlov, HMS Belfast and HMS Liverpool went into reserve in 1952 and were unavailable until Belfast completed its refit in 1959. Of the rest of the legacy fleet only HMS Royalist and HMS Newfoundland were refitted to a standard for more than colonial flagflying and GFS.

Stalin conceived the Sverdlov cruisers at largely defensive, surface defense platforms to counter Nato cruisers in Soviet coastal waters and the Black Sea and to be used to project presence and pressure in 3rd world areas of interest to the Soviet Union. During 1962 the Soviet Navy transferred the cruiser Ordzhonikidze to Indonesia and planned to base two Chapeyev cruisers in a new Soviet naval base in Cuba by the end of the year. Admiral Gorshkov was dissapointed his Sverdlov cruiser fleet had been reduced to 12 units as his aim was to support the Cuban operation with a couple of Sverdlov cruisers to probe the USN preparedness, which seemed to be lacking in daily Nepture maritime patrol plane patrols in the pre ocean satellite age of 1962 when Gorshkov believed cruiser operation was still possible as it might be even today with diminishing maritime patrol forces of Nimrods and Orions and the probability ocean satellites would be taken out by an aggressor.

The Royal Navy post war legacy and later Tiger class cruiser appear to have offered little effective counter to Russian cruiser operation. The Tiger had a speed of only 29.5 knots in the tropics and its effective range was only 4190 miles (D.K. Brown Rebuilding the RN). None of the RN cruisers had the sort of anti aircraft update which would have allowed operation within range of effective Soviet airpower. Only HMS Belfast, HMS Ceylon, HMS Gambia and HMS Bermuda of the legacy Colony and Town cruisers had any effective AA fire control as the earlier British 275 fire control was too unreliable and fragile to be functional. Serious postwar cruiser modernisation had been attempted only on HMS Newfoundland and HMS Royalist which were rapidly sold off to Peru and New Zealand. The Colony and Minotaur class cruiser design was too small and tight to carry an effective surface and aa weaponry or to usefully modernise. One would suggest that fitting 24 3 inch 50 Calibre as the USN Baltimore and Des Moines gun cruisers were updated with would have have been an easier refit for the Tiger class and HMS Swiftsure and Superb. This weapon would have fitted into the existing twin 4 inch mounts and would have avoided the expense of much structual modernisation The 50 calibre 3 inch would have given effective AA coverage out to about 3 miles, equivalent to the Sverdlov anti aircraft capability with 12 auto 4 inch and 32 37mm/60 which most RN fleet air arm Buccanear pilots, was realistically best countered with nuclear weapons. Certainly a torpedo attack by a Daring or Battle or by a 1950s Wyvern or Firebrand was hardly realistic given the short range of the Royal Navy surface attack torpedoes. As a surface weapon post war British cruisers might better have been refitted as intended in the late 1940s with AC versions of the Vanguards improved version of the 5.25 inch gun with a fire rate of 10rpm or the Mk 3 5.25 intended for the Ns2 1944 class with 12rpm. Even the Twin 5 inch mounts fitted to De Grasse and Colbert by the French in the late 1950s would have been more sensible using std US 5inch 38 shells.

In the end, Tiger et al was a very expensive, time consuming and unproductive ‘money pit’ for the Royal Navy.. exacerbating the financial constraints on it. The Sverdlov threat (conceptually) was probably at its worst in the late 1950s… ineffective Tiger gunnery; no credible RN cruiser alternative (though starring roles for HMS Cumberland in the film Battle of the River Plate before being paid off in Barrow!). The assymetric response of the nuclear-capable Buccaneer fighter bomber was not the only assymetric response however… HMS ‘Rearguard’ + Howe + KGV were kept in reserve so long precisely because of the Russian cruiser threat. But by the end of 1957 they had largely been scrapped.. Vanguard being the last ‘Sverdlov swatter’ to go in 1960. Thankfully as with Britain, economic constraints meant a choice between ‘surface’ and ‘submersible’ fleets for the Soviet Union and .. like Britain, they chose the latter so the Sverdlov class was no longer a logistical support priority for Moscow.

The post war French cruisers, Colbert and De Grasse were initially armed with the main DP armament of twin 5 inch turrets of about 48/50 tons displacement, which fired 15/18rpm of a 70lb shell, out of what is technically a 5 inch 54 calibre gun, but the shell are just lengthened version of the standard USN WW2 destroyer and cruiser 5 inch shell from 20.5 inches to 26 inches with the 70lb heavier shell weight

, found heavy for manual loading by USN crews but still doubtlessly more manageable and quicker to load than the RN 5.25 QF . Given the 5.25 shells in use from Dido cruisers proved not to have the penetrative and destructive power expected, and the the low weight of the French post war cruiser 5 inch twin turrets, the possibility of something like a Royal Navy adaption of the French/US gun and turret to use the USN 5 inch 70lb ammunition is an interesting idea. The mid 1960s French navy abandonment of the twin 5 inch turret and the rearming of their cruisers and destroyers with 100mm guns reflected De Gaulle decision in 1965 to withdraw France from an active operational active role in Nato and abandon the use of US munitions and was only partly motivated by a view conventional cruisers were obsolete and medium and heavy cruiser DP guns no longer useful.

Towards the end of WW2 PM W.Churchill perceived the cruiser destroyer in the form of the Battle class and the inchoate Daring design as the core of Royal Navy presence and it was clear Churchill still held similar ideas at the time of the emergence of HMS Daring into service into service in 1952. The 2800 tons of the Battles and Daring designs were limited in the fire control and air warning radars and associated processing systems they could accomodate at the time and even with the addition of MR3 fire control to the Darings in 1961 they hardly represented the answer to Russian cruisers, which could not be effectively dealt with until the Buccannear S2 finally entered service in 1966.

Pingback: Global Maritime History Royal Navy Cruisers (2): HMS Dorsetshire, All around the Empire in twelve years! - Global Maritime History

Pingback: Battleship showdown: Vanguard versus Tirpitz - what might have happened - Navy General Board

Pingback: Global Maritime History Battle of the River Plate – Part VI: Legacy of the South Atlantic Campaign - Global Maritime History