The history between the Royal Navy and sea monsters is intriguing if not extensive. As stories surface in October 2016 about the discovery of a U-boat with its own sea monster story it is a good time to look at the connection.

The UB-85 story goes like this: in April 1918, a Flower-class sloop HMS Coreopsis (incidentally a sister vessel to the surviving – so far – HMS President, formerly HMS Saxifrage, based on the Thames but currently residing at Chatham) encountered UB-85, a UB III-class submarine, on the surface off Stranraer. The sloop fired on the submarine, which attempted to dive before resurfacing and surrendering.

The sloop HMS Coreopsis responsible for sinking UB-85

Nothing particularly strange there. The UB-85 had been recharging its batteries, as submarines must, and had been caught by the sloop. It was night, and Coreopsis was one of the Anchusa group of Flower-class vessels, built as a Q-ship, consequently resembling a merchant ship, which may have momentarily confused the submarine’s crew. The U-boat’s crew was inexperienced, a factor Innes McCartney attributes the submarine’s loss to. It seems likely that damage from gunfire or an improperly sealed hatch led to a leak that prevented the UB-85 from submerging. All 34 crew members gave themselves up.

Supposedly at this point, things started to get a bit more unusual. In words quoted extensively in news stories around the discovery of UB-85 on 19 October, the captain of the submarine, Kapitän-leutenant Gunter Kerch, gave a surprising explanation as to why the UB-85 had been discovered on the surface and had to surrender. Apparently a ‘sea monster’ had attacked the vessel. “Every man on watch began firing a sidearm at the beast,” Krech described, adding that the monster had seized the forward gun mounting and would not release it. Kerch described the creature:

“This beast had large eyes, set in a horny sort of skull. It had a small head, but with teeth that could be seen glistening in the moonlight.” The creature allegedly damaged the forward deck plating before it finally withdrew, which, according to Kerch, was why the Coreopsis was “able to catch us on the surface.”

(See Wreck of German U-boat found off coast of Stranraer on the BBC News website)

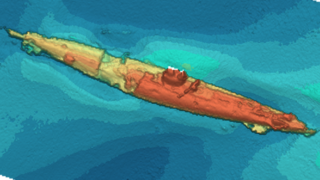

A sonar scan of the recently-discovered U-boat (Scottish Power)

The encounter was not the first between a giant cryptid and a Royal Navy warship. On 6 August 1848, Midshipman Sartoris of the Royal Navy corvette HMS Daedalus alerted the officers on the ship’s quarterdeck to an unusual sight. The captain, first lieutenant and sailing master were all present to see the approach from the ship’s beam of a large creature of a kind none had observed before. Captain Peter M’Quhae, in command of the vessel, described it in his official report to the Admiralty:

“It was discovered to be an enormous serpent, with head and shoulders kept about four feet constantly above the surface of the sea; and as nearly as we could approximate by comparing it with the length of what our maintopsail-yard would show in the water, there was at the very least sixty feet of the animal a fleur d’eau no portion of which was, to our perception, used in propelling it through the water, either by vertical or horizontal undulation. It passed rapidly, but so close under our lee quarter that had it been a man of my acquaintance I should have easily recognised the features with the naked eye.”

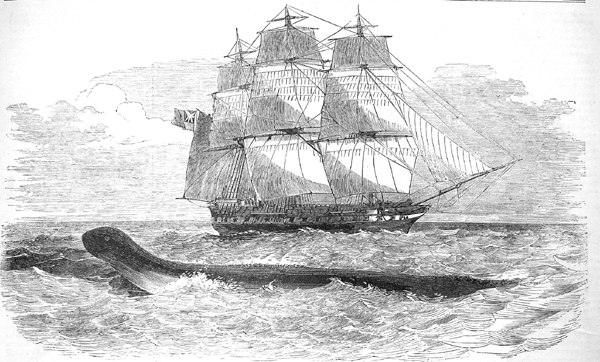

The report was published in the Illustrated London News with engravings depicting the encounter. The response to these reports was indicative of the way sea monsters would be treated in years to come – and can be seen today in the reporting around UB-85. The public and media reacted with credulity and excitement, while experts and the authorities immediately sought to downplay the stories. An MP angrily asked the government how an officer of the Royal Navy had been permitted to make public statements about the sighting, considering it an embarrassment. The naturalist Sir Richard Owen immediately poured scorn on the reports, dismissing it as a misidentified whale or elephant seal.

This may have come as some surprise to the officers involved. Royal Navy officers were expected to be steady, precise and not prone to flights of fancy. Furthermore, in the mid-19th century, the RN’s officer corps was an increasingly scientific body. The developments in meteorology, weaponry, navigation and propulsion in the first half of the 19th century meant that all RN officers had to have an understanding of scientific principles, and a far more scientific outlook than their forebears. The RN was beginning to take more of an interest in exploration and discovery through the naval expeditions to the polar territories of Ross, Parry and Franklin, and no less importantly in the myriad surveying voyages such as those of HMS Beagle. As such, the officers of the Daedalus might have expected their reports to be accepted with at least a neutral outlook.

There’s no proof that the officers suffered any harm to their careers, but M’Quhae never commanded another vessel, and the first lieutenant, Edgar Drummond, left the Navy some years after the incident. That said, the following year the Royal Navy sloop HMS Plumper reported a strikingly similar sighting to that of Daedalus in the North Atlantic.

(See Where Be Monsters? The Daedalus Sea Serpent and the War for Credibility in The Appendix, June 2014, by the author)

The encounter between HMS Daedalus and a sea serpent as illustrated by the ILN

So there are precedents for the strange case of UB-85. There is even another sighting involving a U-boat in WW1 – when U-28 torpedoed the Leyland line steamer SS Iberian off Mizen Head in July 1918, the captain, Georg-Günther Freiherr von Forstner later reported seeing a huge, crocodile-like creature blown out of the water. (For more about this incident see Baron Von Forstner and the U28 sea serpent of July 1915 on the blogs of the Charles Fort Institute)

The problem in the case of UB-85 is that the evidence is much shakier than those earlier ones. The Daedalus reports have proven links to the captain and other officers of that vessel, who repeated them in the face of challenges for years afterwards. It has not, however, been possible in researching this blog to locate a definite source for the comments attributed to Kapitän-leutenant Kerch prior to a book published in 1977 (Sea Monsters: A Collection of Eyewitness Accounts, by James Sweeney), which has been accused of including unsourced and un-evidenced claims. (See Sea Monsters: A Collection of Eyewitness Reports on Scott Hamilton’s How Could This Possibly Be Bad? blog)

The U-28 sea monster has slightly better credentials. Captain von Forstner does not seem to have been quoted publicly about the incident until an article in Popular Mechanics in the 1930s, though the description can be attributed to the German officer and he is reported to have stuck to the story for the rest of his life (see The U-Boat And The Sea Monster on Terry Hooper-Scharf’s sceptical Anomalous Observational Phenomena blog)

Still, despite suggestions that the U-28 incident was completely made up being wide of the mark – contrary to claims made in a blog The Iron Skeptic, see http://www.theironskeptic.com/articles/uboats/uboats.htm, the Iberian did exist and was torpedoed where and when the story says it was (see Wrecksite.eu http://www.wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?71101) – there is very little indeed to give credence to the UB-85 story. The secrecy surrounding Q-ship activities at the time may have had a hand in giving the sense that there was more to the story than was being let on. The German crew might have been messing with their captors. The whole thing might have been made up by Sweeney sixty years after the event.

One can only hope that inspection of the wreck sheds some more light on this intriguing tale.

Until then there’s always the author’s fictional take on the Daedalus encounter…