Nigel Rigby, Pieter van der Merwe, and Glyn Williams, Pacific Exploration: Voyages of Discovery from Captain Cook’s Endeavour to the Beagle. New York and London: Adlard Coles and the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, 2018.

ISBN: 9781472957733. 256 pp. £17.09 Paperback.

Matthew Flinders, the English navigator who led the second circumnavigation of Australia between 1801 and 1802, had previously sailed with the infamous English captain William Bligh. Though “he and Bligh fell out, Flinders managed to pick up three things [during his time on Bligh’s ship Providence], all of which were to affect him in later life: the basics of marine surveying, venereal disease, and an appreciation of the influence that Sir Joseph Banks had in all matters to do with exploration.” (p. 202) This cheeky observation is just one of the many interesting details that dot Pacific Exploration: Voyages of Discovery from Captain Cook’s Endeavour to the Beagle, a book co-authored by Nigel Rigby, Pieter van der Merwe, and Glyn Williams and published by the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. These three eminent scholars (Rigby was formerly Head of Research at the Museum, van der Merwe served as the Museum’s General Editor for over two decades, and Williams is an Emeritus Professor of History at Queen Mary University of London) have contributed several chapters each to this lively and well-written volume.

Pacific Exploration was released in 2018, coinciding with the opening of the Museum’s permanent exhibition “Pacific Encounters.” However, this book is not a catalogue of that exhibition, but rather “a general introduction to European voyages in the Pacific from the 1760s to the 1830s,” as an introductory author’s note describes (p. 4). In fact, Pacific Exploration combines eight chapters, written separately by the three authors, that appeared in two books previously published by the National Maritime Museum in 2002 and 2005. These chapters have been revised, a new final chapter added, and additional “interlude” sections between chapters have been inserted to create the present text.

The book is organized around individual noteworthy European explorers and their voyages in the Pacific, especially around the islands of the southern Pacific. James Cook, not surprisingly, receives ample attention, covered by the first two of the nine chapters. Readers are also introduced to William Bligh, George Vancouver, Matthew Flinders, and Arthur Phillip. Two chapters cover journeys that are perhaps less well-known in the Anglophone world, those of Alejandro Malaspina of Spain and Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse of France. The book ends with a chapter on the HMS Beagle and its most famous passenger, the young Charles Darwin.

Each chapter provides an overview of the voyages led by a particular explorer, noting the expeditions’ aims, itineraries, notable episodes, and lasting impacts. The breadth of the book’s topic and the constraints of space mean that more focused aspects of each expedition, such as the scientific controversies they attempted to solve and the noteworthy figures who made up their crews, only receive so much in-depth discussion. However, the authors still manage to incorporate colorful anecdotes, such as the observation about Matthew Flinders’s acquired knowledge, in order to keep the text lively and engaging. Rigby, van der Merwe, and Williams also note important themes that connect these expeditions, such as their shared context of European political rivalries, the role of scurvy in shaping the experience of extended sea voyages, and the far-reaching networks of trade that existed within the Pacific Rim.

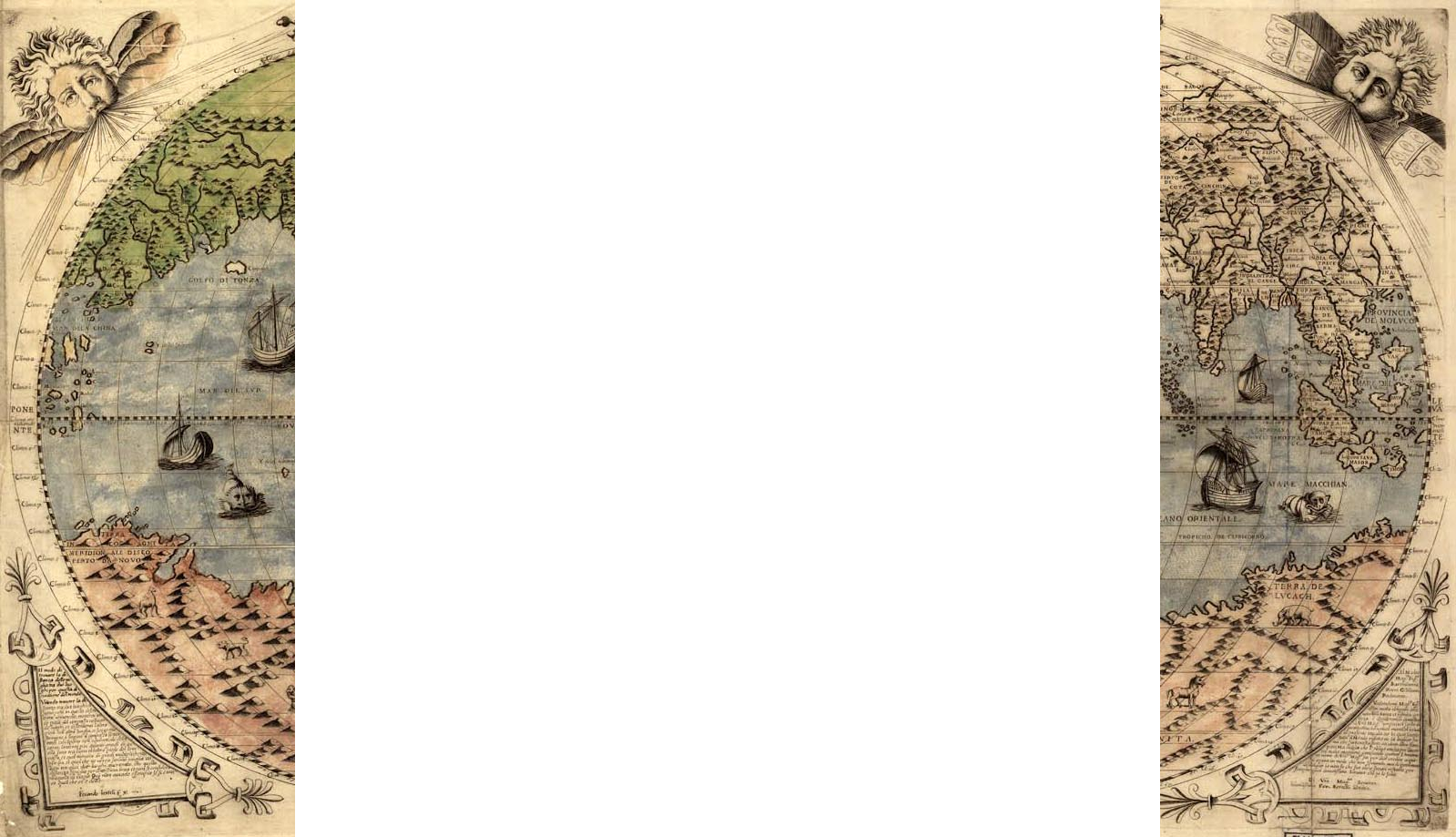

Additionally, the book does make room for a deeper history in one specific area: the artists that accompanied these expeditions. Between several of the chapters there are “interlude” sections that focus on the work of specific artists, providing not just their biographies but also an explanation of their significance to Western art circles and to shaping how outsiders would come to understand the Pacific region. Pacific Exploration is lavishly illustrated with paintings, sketches, and engravings created by these and other expedition artists. Most of the original works are part of the National Maritime Museum’s collection, and one of the strengths of this volume is in showing the depth of the Museum’s artistic holdings related to the Pacific.

This approach—broad in scope but with gestures to scholarly debates—makes Pacific Exploration appealing for general readers looking to learn more about early European incursion into Polynesia and Australia. So too does its sophisticated but accessible tone, which should appeal to both general readers and specialists. Specialist researchers, however, will likely find Pacific Exploration most helpful as background reference for this historical period, especially since a list of further sources on specific voyages and aspects of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century exploration is included at the end of the book.

Overall, Pacific Exploration is a succinct and beautifully illustrated introduction to Europe’s—and especially England’s—incursion into the southern Pacific, and some of the most noteworthy voyages that marked the beginnings of European colonial influence in that part of the world. However, readers would be advised to pick up Pacific Exploration together with a separate book or two that examines the Indigenous Pacific perspective on these voyages. This book’s introduction is quick to note that long before Europeans arrived in the Pacific islands, the islands’ Indigenous peoples had developed sophisticated traditions of ocean navigation and exploration of their own, sets of skills and knowledge that “Europeans were slow to appreciate” (p. 10). Rigby, van der Merwe, and Williams do give brief descriptions of the European sailors’ encounters with local communities, and introduce readers to important Polynesian interlocutors such as Mai and Tupaia, both associates of Cook. Yet this is a history squarely centered on the European actors. Readers wishing to balance this perspective may do well to look at work by scholars like Vanessa Smith or David Chang—or even to peruse the National Maritime Museum’s “Pacific Encounters” gallery, which gives ample space to Pacific voyaging practices, both historic and contemporary. Pacific Exploration is an engaging and well-written narrative—but it is not the whole story.