I am currently on holiday in New Zealand, and over the past few days, Ashley and I have visited Cape Reinga, Waitangi, and Russell. These are historically incredibly important as they represent maritime thresholds and boundaries. This again will be a photo-heavy blog, considering primarily the way that the Pakeha (British/Non-Maori) and Maori narratives and history are presented together, in a non-competitive way. This is another photo-heavy blog. My thanks to the staff at the Waitangi Treaty Grounds and the Pompallier Mission in Russell for their time.

To begin, just a bit of background. My parents are from New Zealand, and they both trace their heritage in that nation back several generations to the migrations of the Canterbury Company. I have always known about the Maori in New Zealand- my Dad in particular knows a smattering of Maori words and things, and I’ve been watching the All Blacks play rugby since 1995. I have also known since I was young that I am part Maori. I’m actually 1/32nd Maori- apparently sufficiently to qualify for one of the designated Maori seats in Parliament (although that would be the *height* of white privilege and entitlement). And the Iwi (tribe) that I’m part of (Ngai Tahu) is apparently one of the more inclusive groups. When it comes to the family histories that my parents have taught me, it’s been almost exclusively a Eurocentric history. On my mother’s side, I’m related to the Earls of Warwick (my grandmother’s a Rich, so we’re directly related to the Earls during the 17th C, but not the *current* Earl). On my Dad’s side, there’s a lot of pride and interest in the New Zealand aspect of the family history, and indeed there’s a book on the Pattersons and McLeans as ‘gentlemen farmers’. The resurgence in the protection of Maori culture since the 1970s and 1980s did have an impact on my childhood- for example, we had a poster for Te Papa, New Zealand’s national museum in Wellington. However, my understanding of the Maori aspects of New Zealand’s history was shockingly poor. Until this trip, I had to look up the date of Waitangi Day every year (and I always missed it).

The first region Ashley and I visited was the Bay of Islands and the Northland, and our visits to Cape Reinga, the Waitangi Treaty Grounds, and to Russell have left a lasting impression regarding how Maori and Pakeha (or European) histories are presented in these official spaces. All three of the places we visited are significant for both groups, and not necessarily for the same reasons. In each location, both aspects of the history are presented in a way that emphasizes that both histories are equally important, and that they don’t complete in either geographic space or narrative space.

The first place we visited was Cape Reinga, the second-most-northern peninsula in New Zealand and a three-hour drive from the Bay of Islands. (All photos can be seen at a larger size)

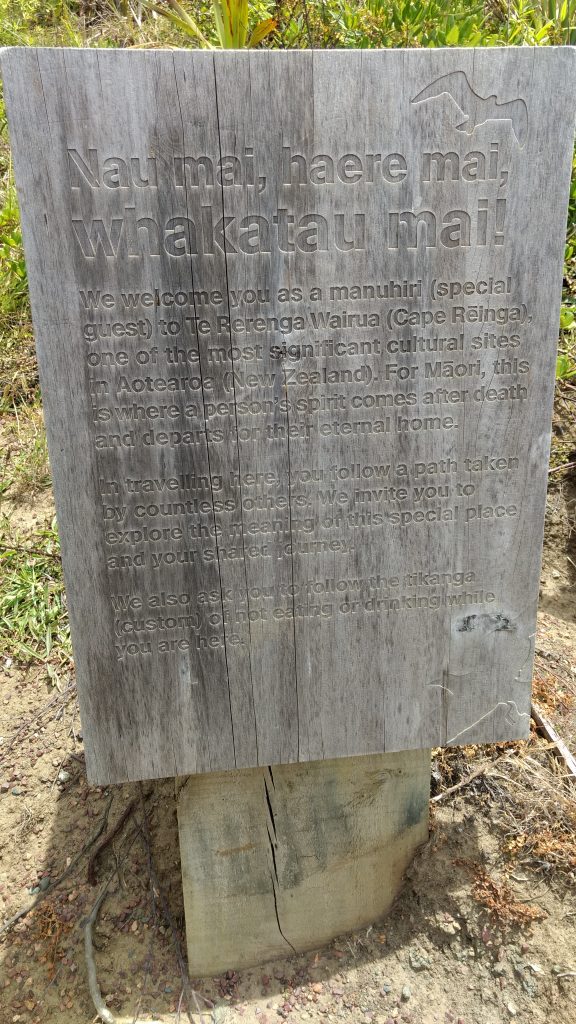

Cape Reinga is a really important spiritual place for Maori, as it represents both one of the first places that the Maoris found when they discovered New Zealand, and also the place where souls are considered to leave the world to go to Hawai’ki (both their ancestral home and the afterlife).

The use of the Maori and English together on a sign isn’t notable- that happens everywhere in New Zealand (and all government organizations, for example, have both Maori and English names). What had the biggest impression on me was the way that the ‘English’ narratives, such as about Abel Tasman and James Cook, were presented on an absolutely equal basis to the narratives of the Maori explorers.

These narratives are not presented as options, as in you can believe the European or the Maori stories. They are presented with equal weight and authority. The images presented here are only a portion of the panels at Cape Reinga. It’s an absolutely beautiful place to consider historical interactions, where the Pacific Ocean and the Tasman sea meet.

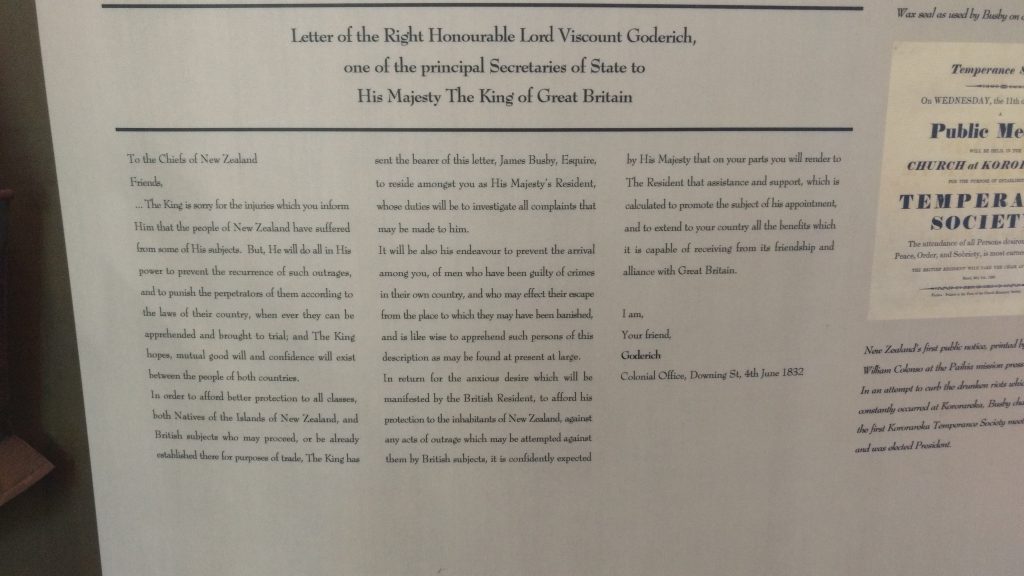

The next day, Ashley and I visited the Waitangi Treaty Grounds, in the Bay of Islands. This is an incredibly important place for New Zealand history. It has for centuries been an important meeting place for North Island Maori Chiefs, and was the place where Captain William Hobson presented what would become the Treaty of Waitangi in February of 1840.

What’s really interesting about Waitangi is the way that it is a brilliant demonstration of the way that Maori and European histories come together in the same physical space. On the plateau that was the meeting space for the Maori chiefs, and later Hobson, there sits both the marae (or meeting house) and the house of the first British Resident (which was shipped over from Sydney after being built and taken apart. As our tour guide quipped, it’s the first Ikea House in New Zealand).

The Waitangi Treaty Grounds are an important shared space. The Resident’s House has been converted into a museum showing the European perspective with a full European style garden.

In addition to the Marae, there is also the Canoe House, which contains the Waka Taua, which I blogged about previously,

What is made extremely clear by the tour and the museum is that the Waitangi Treaty Grounds are a Maori space, but that the presence of the European history doesn’t compete, it cohabitates. It’s a brilliant presentation of a basic understanding of the local Maori history prior to the Treaty, and the relationship between the Maori and the English in the 1830s and the 1840s.

A counterpoint to Waitangi is Russell, which is pretty much directly across the bay. Russell (or Kororāreka) was a major town in New Zealand, and particular an important port for merchantmen and whalers. The population also included individuals who had been transported to Australia. One of the major forces driving Maori and English interaction was Maori demands that the English take responsibility for their escaped convicts and apply their laws to what had effectively become the Mos Eisley of the South Pacific.

The Pompallier Mission in Russell was the site of a Roman Catholic printing press from 1838. Bishop Pompallier was dispatched from Lyons to create missions across the South Pacific, and the mission in New Zealand was the counterpoint to the Church Mission Society mission in Paihia (a mere 400m North of Waitangi). Where the English missionaries situated themselves in what they considered to be heaven, the Roman Catholic mission (composed of Pompallier and some Marist brothers) placed themselves in the middle of the lawlessness and groghouses. The mission was responsible for the printing of 30,000 religious books in the Maori language from 1842 to 1849, including a nearly 10 month long interlude in 1845/6 during the ‘Flagstaff War’ when the lead type was removed from Kororāreka for safekeeping.

Prior to 1840 and at the signing of the Treaty, Waitangi was the capital of New Zealand. It was an important maritime commercial centre. Pompallier House and Christ Church are the only buildings in Russell still remaining from the ‘Flagstaff War’ (and are the oldest industrial site and church in New Zealand, respectively). They bear the marks of events that have two very different narratives, from the Maori and English perspectives. Again, it is clear that these narratives are not in competition. The history presented in this space is a joint Maori and Pakeha history; of the time prior to the Treaty of Waitangi, the circumstances for the signing of the treaty, and the aftermath. In 1841 the capital was moved to the new settlement of Auckland, followed by much of the shipping that had made the Bay of Islands so prosperous. This was only part of the significant tensions that bloomed between the English and the Maori following the signing of the Treaty of the Waitangi. The story of the Pompallier mission, and the history presented by its current staff is a Maori, British and French story. Again there is no competition for what is the most valid, or the ‘correct’ perspective. Each narrative is given space, and equal weight.

These sites were inspirational, because they illustrate that First Nations and European narratives and perspectives can coexist, and can be provided equal space in our history. In 1975, the New Zealand government created a commission for reconciliation of Maori claims. The results of those 40 years of reconciliation are clear in the way that Maori and Pakeha histories are presented at places like Cape Reinga, Waitangi and in Russell. The process isn’t complete, but the ongoing integration of the perspectives into a complex whole provides a better sense of the history than distinct, and distinctly competitive presentation of First Nations and European perspectives that I am used to in Canada. The Canadian government has been, and continues to be reluctant to actually engage in reconciliation with First Nations. Until they do so, it will be very difficult to create the kind of integrated narratives that are present at the New Zealand historical sites I’ve visited on the trip so far.