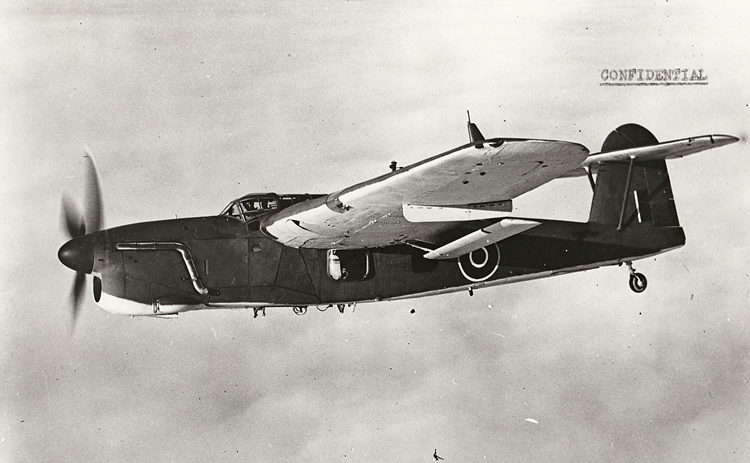

The Fleet Air Arm Museum has embarked on one of the most important restoration projects in British naval aviation history – the reconstruction of a Fairey Barracuda Torpedo/Dive Bomber from a quantity of wreckage. This will fill a major gap in the existing WW2 Fleet Air Arm types, and make an excellent focal point for boosting the profile of the work done by FAA TBR squadrons in the second half of WW2. This included everything from high-profile dive bombing missions against the Tirpitz to flying cover against E-boats during the vital but unglamorous operation to lay a temporary fuel pipeline across the English Channel after the D-Day landings. It served in the North Sea, the East Indies, the Mediterranean and the Western Approaches, as well as acting as a training aircraft and a testbed for tactics and development after the war as well as continuing its role as a frontline carrier strike aircraft.

I am particularly keen to help boost the profile of this wonderful project as I unwittingly missed an opportunity to do so when my book on the aircraft came out last November. Although I had been fortunate enough to photograph the extensive collection of airframe parts collected from wreck sites over decades at one of the periodic public openings of the FAAM reserve collection, the text had been finalised just before the current project got going. The status of the restoration was still unclear at the moment the book was prepared for publication. I therefore missed the chance to reflect the thoroughness and attention to detail going into the restoration, which is a joy to behold. Any aircraft is a collection of thousands of components, and as each of those components is examined, prepared, restored, reconditioned and installed into the project, it tells its own story – in this case with admirable transparency. (And I am also keen to apologise to the FAAM for not including an acknowledgement for the help they provided – there were so many individuals and organisations that provided me with invaluable, selfless assistance, and the omission of the FAAM from that long list was a mistake I regret – I hope this will help make up for it).

No complete Barracuda has survived, despite the aircraft remaining in UK service long after WW2, until 1952 (and, a little known fact, in France until 1953). Unlike its stablemate the Firefly, contemporary the Grumman Avenger, and predecessor the Swordfish, none passed into civil ownership, or lasted long enough in scrapyards to catch the preservation movement’s eye. Moreover, unlike some other types that are extinct in complete form, such as the Blackburn Skua, only the Fleet Air Arm Museum has been saving major components with a view to a possible restoration.

The museum has proceeded gradually towards reconstructing a complete Barracuda since the substantial remains of a Mk.II were recovered in 1971. Barracuda DP872 was ordered from Boulton Paul and delivered in July 1943. It was taken on charge by 769 (Deck Landing Training) Squadron in November of that year. In August 1944, DP872 took off from Maydown on a flight to Easthaven, but five miles short of the airfield the Barracuda spun and crashed in a bog. The crew, Sub Lieutenant DH Oxby, Sub Lieutenant FR Dobbie and Leading Airman DAJ Mew were all killed. In 1971, a team from the Fleet Air Arm Museum and the Royal Engineers recovered the wreckage of DP872 from the bog where it had lain since the accident. The crewmembers were identified and buried together in Faughanvale (St Canice) Church of Ireland churchyard, Eglinton.

For much of that time, the recovered sections of DP872 have been in storage, steadily being added to when other recovery missions brought back material from crash sites. These included LS931 of 815 Squadron which crashed on Jura recovered in 2000, Mk.IIs DR306 and PM870, and Mk.III MD953. In the 1990s, the Museum commissioned Viv Bellamy to reconstruct the nose section forward of the firewall. Little remained of this apart from the engine, with none of the cowling surviving in a remotely useable condition, so it made sense to reconstruct this part of the aircraft in one go as so much new-build was required.

In 2010, the Museum engaged the Bluebird Project to carry out the remainder of the restoration, having by this time acquired enough material to recreate a Barracuda that would be around 80 per cent original. Unfortunately, for various reasons, the association with the Bluebird Project ended before much tangible progress had been made, but by now the FAAM was committed to continuing the restoration to a conclusion. The Museum has acquired an enviable reputation for ‘airframe archaeology,’ with the Vought Corsair and Grumman Martlet projects painstakingly taking the aircraft back to their contemporary paintwork and examining them forensically to discover a wealth of historic detail. The Museum had also been responsible for previous reconstructions from wreckage, such as the Fairey Albacore N4389, although in these cases much of the work was carried out by outside agencies. In the case of the Barracuda, the vast majority will be done in-house.

It is astonishing the extent to which battered, corroded components can be rendered as-new. The skills on display through the regular updates are astounding. In fact, the condition of some of the components beneath a layer or six of dirt and surface corrosion is eye-popping. A rubber inner tube for the tailwheel is perfectly useable. The adjusting mechanism for the rudder pedals spins with buttery smoothness after the parts were dismantled, carefully cleaned and zinc-plated. The Barracuda was very much a semi-monocoque design with the forward fuselage based heavily on a tubular spaceframe structure. Many of these heavyweight tubes, once cleaned and treated, are indistinguishable from new.

This process has also laid bare just what a complicated aircraft the Barracuda was – in many ways, over-complicated. The mix of materials and types of structure in the fuselage is mind-boggling, with tubular framework, pressed sections, castings and built-up riveted parts all linked together. The Barracuda had a lengthy development and suffered from multiple changes to the requirement. It was also designed to be built in modular sections that would be largely completed before being brought together at final assembly. Sub-assemblies built at one factory had to be able to fit those built at another to ensure standardisation across the four companies building Barracudas, and this undoubtedly led to added complexity in the structure.

And little details that speak of the conditions the Barracuda was built under keep coming to light. A green-dyed magnesium rivet that had fallen into the rear fuselage floor area and not been recovered remained where it lay from the time the aircraft was undergoing construction to the present. This was a mass-produced aircraft with production schedules to keep to. No time to go fishing out a dropped rivet.

I would urge anyone with an interest in naval aviation to make regular visits to the project’s Facebook page and donations to help fund it can be made at the JustGiving page here

It’s fascinating to see the aircraft coming along, bit by bit, and possible to see the guts of the restoration in a way that would be impossible from simply looking at the completed airframe – immensely satisfying though that will doubtless be.

I saw a photo of the recovery of a Barracuda from the Solent in my copy of ‘The Times’ this morning. I have high hopes that this will lead to further success with your Barracuda restoration.

I was born in Gosport during the war and had the luxury of two Fleet Air Arm stations nearby, HMS Siskin and HMS Daedalus. From the back room of our house we could watch Fireflys, Sea Furys and others doing circuits and bumps at Siskin. My greatest joy was to walk to Siskin, go round the perimeter track and come upon, Swordfish, Fireflys and Barracudas waiting to be used for fire practice. I sat inside each one, very low in the seat imagining wonderful adventures. I must have been about eight years old.

Good Luck with the Barracuda.

I would like to be kept informed of the Barracuda restoration project at the Fleet Air Arm Museum. My father and brother are both World War II veterans and I am a Vietnam Veteran. I have developed a keen liking for World War II aircraft, and I think it is a terrible shame that one Barracuda has not survived.