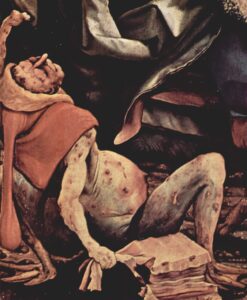

“Temptation of St. Anthony” (detail) by Mathias Grunewald (1480–1528), ca. 1512, showing a man suffering from St. Anthony’s Fire (Unterlinden Museum, Colmar, France; public domain, courtesy: The Yorck Project, 2002).

Welcome to the first instalment of our new series on “Health at Sea in the Age of Sail”! Every month, we will post a new article discussing common or not-so-common afflictions encountered below decks on the wooden sailing ships of the day. This first instalment addresses a less well-known condition, known as erysipelas, which—although usually not fatal—was quite traumatising to the common sailor nevertheless.

In the medical lexicon of the early modern world, few diseases from the Age of Sail—roughly the mid-sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century—were as immediately alarming in appearance or as poorly understood as erysipelas. Known as St. Anthony’s Fire, ignis sacer, or simply ‘the rose’, it announced itself dramatically: a sudden fever followed by a sharply demarcated, vivid red swelling of the skin, hot to the touch and often exquisitely painful. It spread across a sailor’s face, limbs, or trunk, creeping across the skin and sometimes advancing inch by inch within hours.

Its fiery aspect inspired dread among patients and surgeons alike, who interpreted the disease as an external manifestation of internal corruption. In the confined, unhygienic, and injury-prone environments of wooden sailing vessels, erysipelas was both common and dangerous, capable of progressing rapidly to delirium, gangrene, or death. It afflicted sailors, soldiers, convicts, and surgeons alike, leaving a trail of morbidity—and often mortality—across the maritime empires of Europe.

Early modern interpretation

Although modern medicine identifies erysipelas as an acute streptococcal infection of the superficial dermis (the skin’s upper layer), early modern practitioners understood it through a far older intellectual tradition rooted in humoral imbalance, miasmatic corruption, and constitutional weakness. Hippocratic writers distinguished erysipelas from deeper inflammatory conditions by its superficial nature and sharply defined borders, noting its tendency to migrate across the body.1 Galen (129–216 CE) and later medieval authorities framed the disease within humoral theory, attributing it to an excess or corruption of yellow bile that ‘rose to the surface’ of the skin.2

By the early modern period, erysipelas was not considered a specific disease but an inflammatory eruption caused by ‘acrimony’ or corruption of the blood, often provoked by external injury or internal excess. Thomas Sydenham (1624–1689) called it a febrile disorder marked by “a redness of the skin, with pain and swelling, chiefly affecting the face.”3 Surgeons described it as arising at the margins of wounds, where the skin became red and painful before the inflammation spread outward. In severe cases, suppuration (pus discharge), sloughing (shedding) of tissue, or progression to gangrene could follow. Crucially, erysipelas was understood as a systemic disorder, not merely a local skin complaint, a belief that profoundly shaped therapeutic practice.

Medical writers distinguished erysipelas from phlegmonous inflammation, erythema (abnormal redness), and gangrene, although boundaries between these conditions remained indistinct. It might arise spontaneously, but more often it was associated with wounds, surgical incisions, ulcers, or even minor abrasions. The Age of Sail provided ideal conditions for its development. Ships were crowded, damp, and poorly ventilated; fresh water was rationed, clothing rarely washed, and wounds were all but inevitable. Even minor cuts—from ropes, spars, or splinters—could provide an entry point for infection.

No relief on shore

Naval hospitals and hospital ships fared little better. Overcrowding, reused dressings, and unwashed instruments facilitated postoperative erysipelas, although contemporaries explained outbreaks in terms of bad air, seasonal influence, or individual constitution. Some surgeons observed cases spreading from bed to bed, but this rarely resulted in systemic isolation. James Lind (1716–1794) observed that inflammatory diseases were common in warm climates, where heat and humidity exacerbated putrefaction.4

Erysipelas was frequently reported following amputations or abscess drainage, especially when instruments were reused with only cursory cleaning.5 Malnutrition increased vulnerability: vitamin deficiencies weakened the skin and impaired healing; chronic illness reduced resistance. Alcohol abuse, widespread among sailors, was also thought to predispose individuals to inflammatory disorders by ‘heating the blood’.6

Symptoms in context

Erysipelas additionally carried rich cultural and religious meaning. The term St. Anthony’s Fire was shared with ergotism (a form of poisoning); the two conditions were not always clearly distinguished. Both were associated with burning pain, redness, and putrefaction, and both were sometimes interpreted as divinely inflicted. In Catholic Europe, St. Anthony the Great (251–356 CE) was invoked as protector against fiery skin diseases, while in Protestant maritime cultures the language of fire and corruption persisted. Sailors spoke of the flesh being ‘set alight’, and surgeons warned of internal heat seeking an outlet through the skin. Such metaphors were not merely rhetorical: they shaped therapeutic approaches aimed at cooling, diverting, or expelling the offending humors.

Shipboard accounts describe patients developing chills, headache, and fever, followed by the rapid appearance of a bright red, swollen patch of skin. The affected area was hot, painful, and tense, with a raised edge advancing visibly over time. Facial erysipelas was particularly feared. Surgeons noted swelling of the eyelids, nose, and lips, sometimes leading to disfigurement or temporary blindness.7 When the scalp was involved, delirium and coma were common, suggesting that erysipelas could ‘strike inward’ and affect the brain. In severe cases, vesicles or bullae formed and ruptured, leaving the skin prone to gangrene. Septic complications—although not fully understood—were recognized through rapid deterioration, foul discharge, and death despite treatment.

Shipboard treatment

Treatment at sea reflected broader contemporary medical debates. The dominant approach was antiphlogistic: reducing inflammation by lowering humoral excess. Bloodletting was widely employed, particularly in otherwise healthy patients and early in the disease.8 Surgeons bled either from the arm or, in facial cases, locally from the temples or behind the ears. Purgatives and emetics were administered to cleanse the body, commonly using calomel, jalap, or antimony.

Cooling regimens were standard: patients were kept on thin gruels, barley water, or whey and denied meat or alcohol.9 Internal remedies aimed at ‘cooling the blood’ included saline purgatives, antimonials, and diluting drinks. Rest was prescribed but difficult to enforce; sailors were valuable manpower, and unless severely ill, many returned to duty prematurely, risking relapse.

Local treatments varied widely. Cooling poultices made from bread, milk, vinegar, or lead-based preparations (such as Goulard’s extract) were commonly applied.10 Herbal remedies—including chamomile, elderflower, and plantain—were used for their supposed anti-inflammatory properties. Mercury ointments occasionally appeared, particularly when erysipelas was confused with venereal disease.11 Some surgeons preferred warm poultices when suppuration was anticipated, while blistering at a distance from the affected area was employed to draw inflammation away from vital organs. Incision of erysipelatous skin was generally avoided, however, as it was believed to aggravate the condition.

Prognosis and morbidity

Naval hospital records from the late eighteenth century indicate that erysipelas was a significant cause of morbidity, although less lethal than typhus12 or yellow fever.13

Its tendency to incapacitate men for prolonged periods posed serious operational challenges during long voyages and military campaigns. Relapse was common, and some individuals appeared prone to repeated attacks, thus reinforcing the belief that erysipelas reflected constitutional weakness rather than external contagion. Although precise mortality figures are hard to come by, contemporary accounts suggest that the disease contributed substantially to non-combat losses, especially in tropical climates where heat and humidity were thought to exacerbate inflammatory disorders.

Towards modern insights

One of the most persistent debates surrounding erysipelas concerned contagion. Surgeons observed that cases often appeared in clusters, particularly in hospitals and crowded ships, yet classical doctrine resisted the idea of person-to-person transmission.14 By the early nineteenth century, some practitioners argued that erysipelas could be communicated through contact, particularly via contaminated dressings or instruments. These observations, although lacking a microbial framework, marked an important step toward modern understanding. It was not until the later nineteenth century that erysipelas was conclusively linked to Streptococcus pyogenes. However, the empirical practices of ships’ surgeons—such as isolating patients and improving ventilation—anticipated later antiseptic principles.

Erysipelas in the Age of Sail exemplifies the uneasy balance between inherited theory and lived experience that characterized early modern medicine. For naval and merchant surgeons, it was a familiar and formidable adversary, shaped by the brutal realities of maritime life. Constrained by humoral theory and limited therapeutic tools, they nevertheless developed pragmatic strategies that sometimes succeeded in controlling a potentially fatal illness. Seen in historical perspective, erysipelas reminds us that maritime disease was not limited to exotic fevers or dramatic epidemics. Common, painful, and visually striking, it was part of the everyday medical landscape aboard ship—another fiery visitation endured by those who lived and worked upon the world’s oceans.

References

- Hippocrates and Jones, WHS (transl.). IV. Aphorisms. (London: William Heinemann; New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1931).

- Galen and Siegel, RE (transl.). On the Affected Parts. (Basel, New York: S. Karger, 1976). Original title: De locis affectis.

- Sydenham, T. Observationes Medicae. (London, 1676).

- Lind, J. An Essay on the Most Effectual Means of Preserving the Health of Seamen, in the Royal Navy. Containing directions proper for all those who undertake long voyages at sea … or reside in unhealthy situations. With cautions necessary for the preservation of such persons as attend the sick in fevers. (London: D. Wilson, 1762).

- Porter, R. Disease, Medicine and Society in England, 1550–1860. (Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

- McLean, D. Surgeons of the Fleet. The Royal Navy and its Medics from Trafalgar to Jutland. (London: I.B. Tauris, 2010).

- Blane, G. Observations on the Diseases of Seamen. (London: Joseph Cooper, 1784).

- Loudon, I. Medical Care and the General Practitioner 1750–1850. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986).

- Buchan, W. Domestic Medicine; or, the family physician; being an attempt to render the medical art more generally useful, by shewing people what is in their own power both with respect to the prevention and cure of diseases. Chiefly calculated to recommend a proper attention to regimen and simple medicines. (Edinburgh: Balfour, Auld and Smellie, 1769).

- Waring, EJ. Pharmacopoeia of India. (London: Allen, 1868).

- de Grijs, R. “The ships’ surgeons’ toxic toolkit,” Hektoen International, https://hekint.org/2023/06/07/the-ships-surgeons-toxic-toolkit/ (Spring 2023).

- de Grijs, R. “Ship fever: A malignant disease of a most dangerous kind?,” Hektoen International, https://hekint.org/2024/04/15/ship-fever-a-malignant-disease-of-a-most-dangerous-kind/ (Spring 2024).

- Office of the Commissioners of Sick and Wounded Seamen. Royal Navy Sick and Hurt Board correspondence. Admiralty series ADM 97 (in-letters, 1702–1862) and ADM 98 (out-letters, 1742–1833). (Kew, UK: The National Archives).

- Ackerknecht, EH. History and Geography of the Most Important Diseases. (New York: Hafner, 1972).